If you regularly read The New York Times or The New Yorker, you’ve probably already seen Roman Muradov’s compelling illustrations. If you’re a fan, you also know about his strange and wonderful Yellow Zine comics (and if you don’t know them, check out his adaptation of Italo Calvino).

Muradov’s début graphic novella (In a Sense) Lost and Found was released recently by Nobrow Press, and it’s a beauty—rich, imaginative, playful, and rewarding. And it smells good.

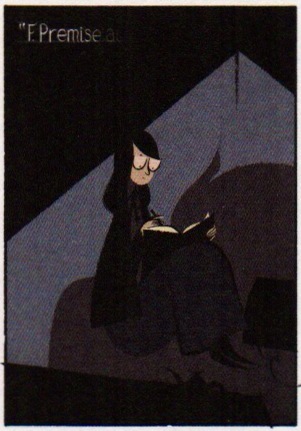

(In a Sense) Lost and Found begins with a nod to Kafka’s Metamorphosis:

Although we’re told by the narrative script that our heroine F. Premise (faulty premise?) “awoke,” the surreal world Muradov creates in Lost and Found suggests that those “troubled dreams” continue far into waking hours. The story runs on its own internal dream-logic, shifting into amorphous spaces without any kind of exposition to guide the reader who is, in a sense, as lost as the protagonist becomes at times on her Kafkaesque quest.

What is F. Premise’s mission? To regain her innocence, perhaps, although only the initial narrative script and the punning title allude to “innocence.” The characters seem unable or unwilling to name this object; each time they mention it, their speech trails off elliptically, as we see when Premise’s father (?) confronts her at the breakfast table:

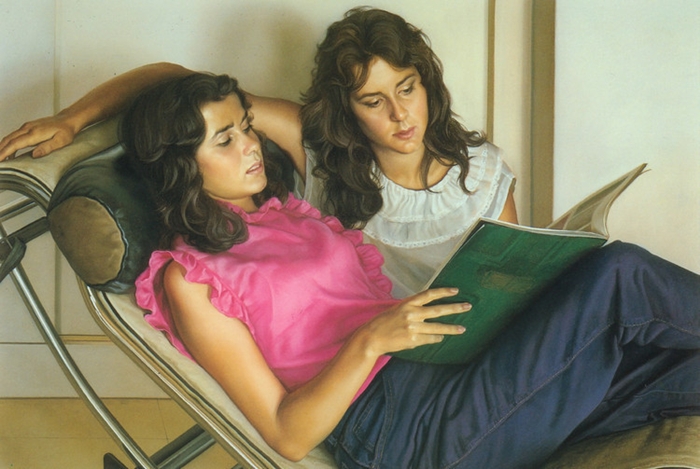

Muradov’s imagery suggests Kafka’s bug again—the father’s antennae poke over the broadsheet he’s reading (the book is larded with readers), his strange mouth sagging out under it. Even more Kafkaesque though is Muradov’s refusal to reveal the father’s face, the face of authority, who sends his daughter back up to her room where she must remain locked away.

She sneaks out of course—would there be an adventure otherwise?—and it turns out that faceless father is right: F. Premise falls (literally) under the intense gaze of the community. F. Premise is startlingly present to others now by virtue of her absent virtue.

Muradov uses traditional nine-panel grids to tell his story, utilizing large splashes sparingly to convey the intensity of key moments in the narrative. The book brims with beautiful, weird energy, rendered in intense color and deep shadow. Muradov’s abstractions—pure shapes—cohere into representative objects only to fragment again into abstraction. (Perhaps I should switch “cohere” and “fragment” here—I may have the verbs backwards).

The art here seems as grounded in a kind of post-cubism as it does in the work of Muradov’s cartooning forebears. In the remarkable passage below, for example, our heroine moves from one world to another, her form nearly disappearing into complete abstraction by the fifth panel (an image that recalls Miró), before stabilizing again (if momentarily) in the sixth panel.

It’s in that last panel that F. Premise returns to her adopted home (of sorts)—a bookstore, of course. Earlier, the kindly owner of the bookstore loans her a pair of old plus-fours, and all of a sudden her identity shifts—or rather, the community shifts her identity, their penetrating gaze no longer trying to screw her to a particular preconception. Identity in Lost and Found is as fluid and changeable as the objects in Muradov’s haunting illustrations.

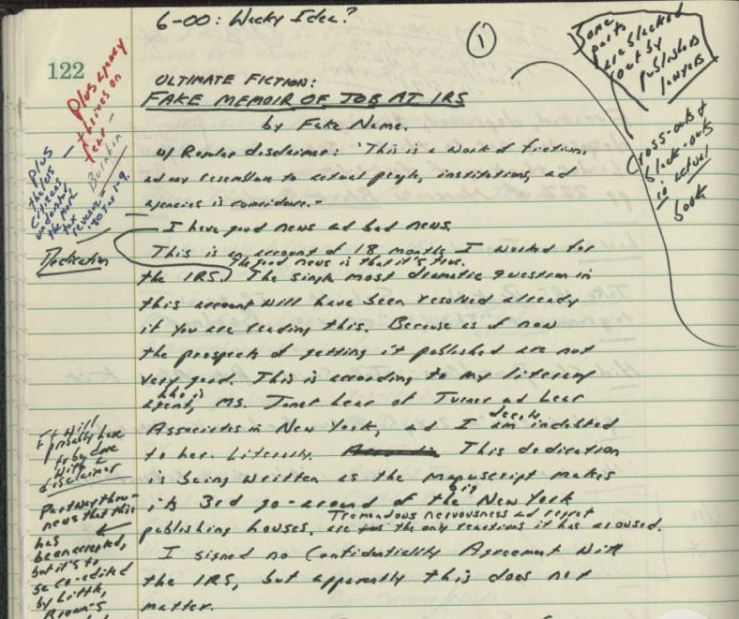

I have probably already belabored too much of the plot. Suffice to say that our heroine’s quest takes strange turns, makes radical shifts, she descends up and down and into other worlds. Embedded in the journey is a critique of nostalgia, of the commodification of memory (or, more accurately, the memory of memory). Is our innocence what we thought it was? Can we buy it back like some mass-produced object?

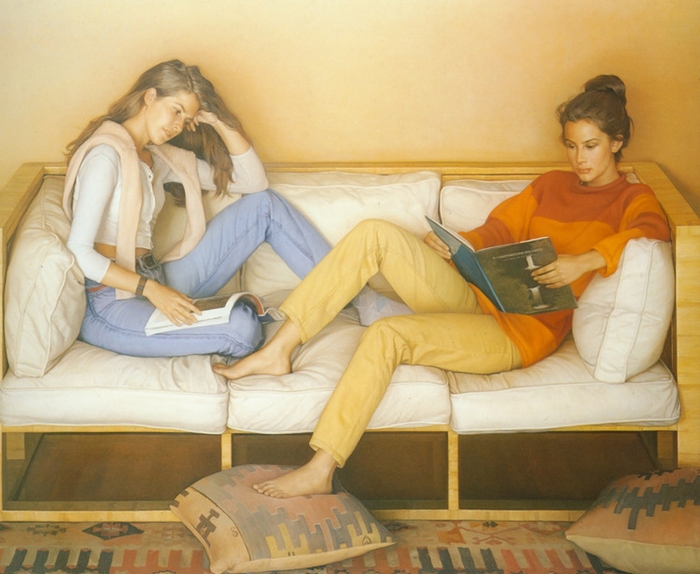

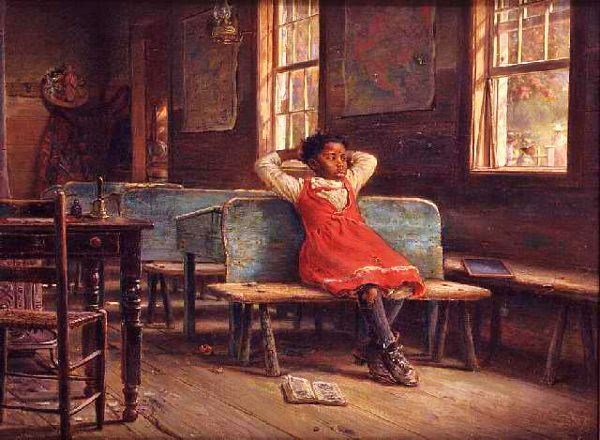

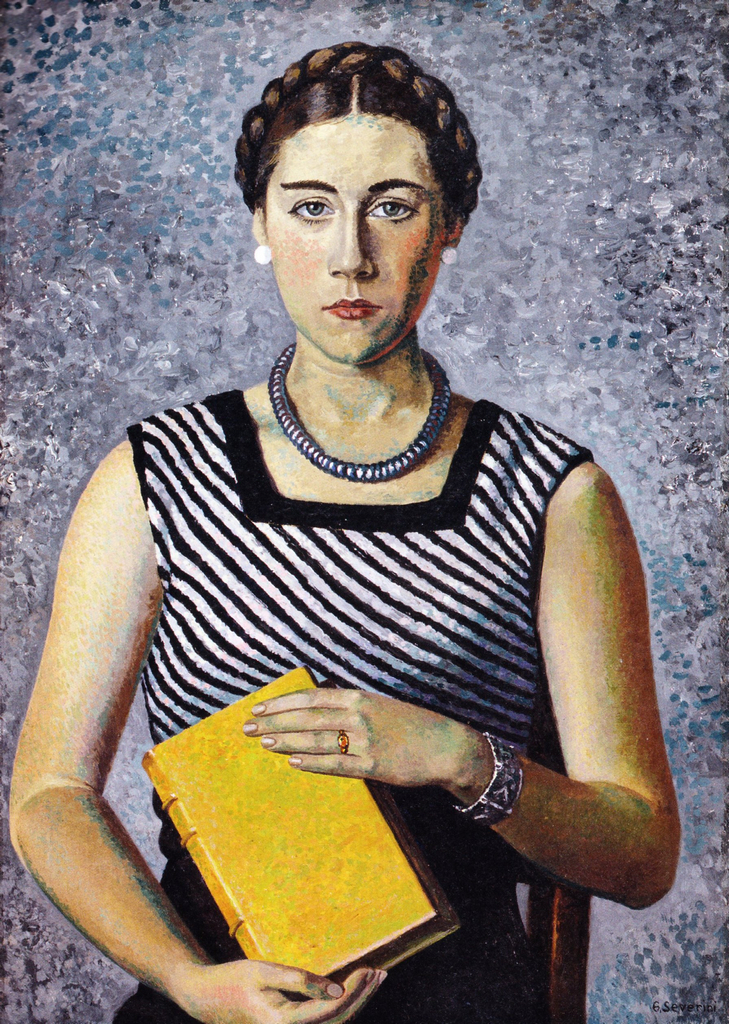

As I noted before, Lost and Found is stuffed with images of readers. There’s something almost Borgesian in the gesture, as if each background character might be on the threshold (if not right in the middle of) their own adventures.

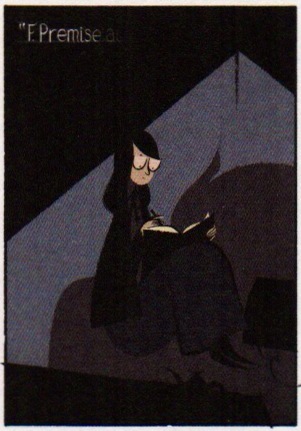

It’s in the book’s final moments though that we see a move from reading to writing: Our heroine F. Premise picks up the pen and claims agency, writes her own life. She is indeed the narrative voice after all, the imposing script that, like some all-knowing hand, guided us into the narrative in the first place, only to disappear until the end.

I loved Lost and Found, finding more in its details, shadowy corners, and the spaces between the panels with each new reading. My only complaint is that I wish it were longer. The book is probably not for everyone—readers looking for a simple comic with an expository voice that will guide them through a traditional plot should probably look elsewhere. But readers willing to engage in Muradov’s ludic text will be rewarded—and even folks left scratching their heads will have to admit that the book is gorgeous, an aesthetic experience unto itself. And it smells good. Highly recommended.