Novels make lousy gifts.

Now, if you have even a passing acquaintance with this little blog, you know that I love novels, that Biblioklept primarily focuses on novels, and that I love books in general. I am not anti-novel or anti-giving-novels-as-gifts. Send me a novel as a gift. I will appreciate it (or trade it toward another book, which is kinda sorta a form of appreciation).

I went to my favorite bookstore today, in fact, to buy some books for Christmas presents. But I restrained myself from picking up novels as gifts.

If you love books like I do, I’m sure that some of your most favorite gifts ever have been novels. Some of my most favorite gifts have been novels. The remaindered copy of The Lord of the Rings (from the South Barwon Library that some friends of the family gave me on Dec. 5th, 1990 when we visited Melbourne (the one in Australia, not Florida)) is probably one of my all-time favorite gifts. I know the exact date because the nice lady who gave it to me wrote a kind note in book and included the date in her note.

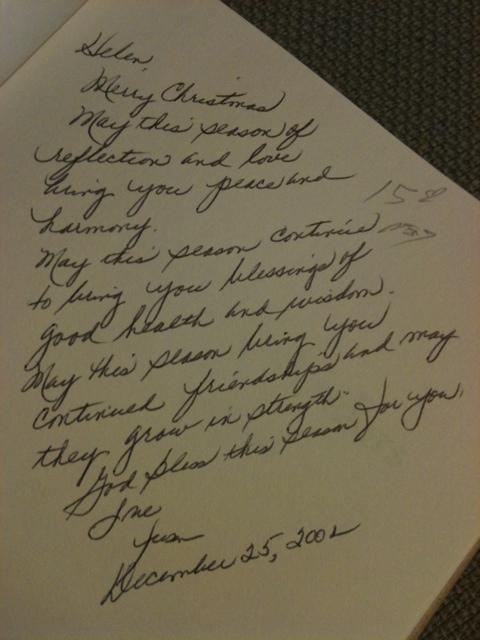

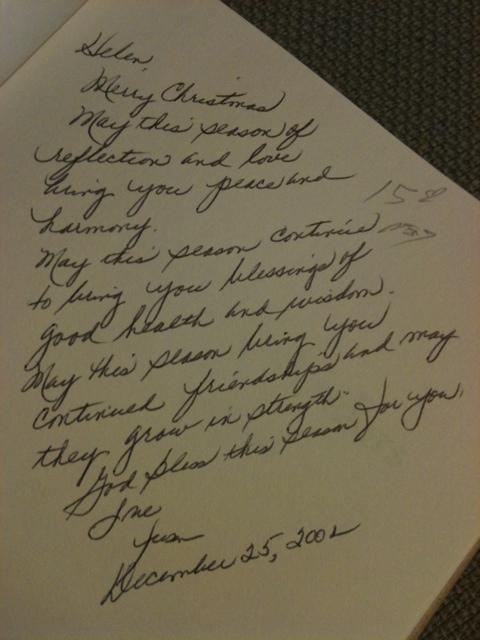

I could never bear to get rid of an inscribed book given as a gift, but lots of people do get rid of inscribed books. This is a monstrous practice, one that attests to just how easily people will discard your oh-so-earnest gifts. If you spend a lot of time in used bookstores (I do) you will come across these sad markings. Because it’s close at hand, and I’m aware of its inscription, I’ll share the note that Jean wrote to Helen (no, of course I know neither of them) in my copy of Balthus’s memoir, Vanished Splendors:

I am aware that the memoir of a pervy artist is not the same as a novel, and that, as my first illustrating example, I already seem to be losing my metaphorical balance, but again, it was close at hand, right near the Tolkien in fact (by the bye, Vanished Splendors is pure gold).

In any case, I think Balthus’s memoir “reads” like a novel, which is to say that it’s mostly big chunks of text that require time and energy to decipher, set against the backdrop of TV, internet, movies, etc. It has some pictures, but not many. There’s no gimmick to it. I’m guessing that Helen just wasn’t into Balthus, or, if she had a passing interest in his art, it didn’t translate into wanting to read his memoir. She certainly didn’t read any of it (yes, I have a special sense that tells me when a book has been read. This baby was a virgin). Every time I look over the book, I feel sorta bad for Jean, whose gift seems to have gone unappreciated (by Helen; not by me. I was happy to pick it up used).

To return to an earlier point: yes, some of our favorite gifts ever might be novels. However, most of the life-changing novels I received were rarely given as birthday or Christmas gifts. They weren’t gifts of obligation, if you’ll forgive the ugliness of that term. Most of the great novels that were given to me were handed along free of occasion, given because the giver thought (knew) I should read them.

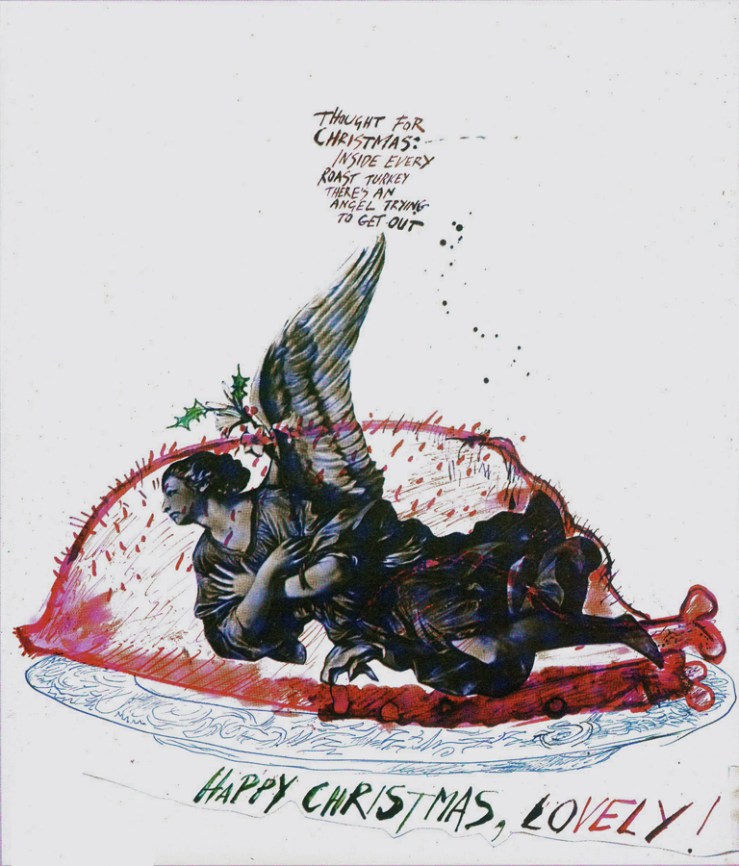

At Christmas though, we feel obliged to give. Sometimes we get some great novels as gifts. More often though, it seems like that relative who knows you “like to read” gives you a novel by, I dunno, Clive Cussler or Tom Clancy. The worst though are those tiny little hardback books that are designed specifically to be gifts, little faux-tomes of faux-philosophy usually connected to golf or angels or some other bullshit (I was horrified last year when DFW’s “This Is Water” speech got this treatment). Anyway, if you like books, you probably just go trade in this bullshit toward the books you like.

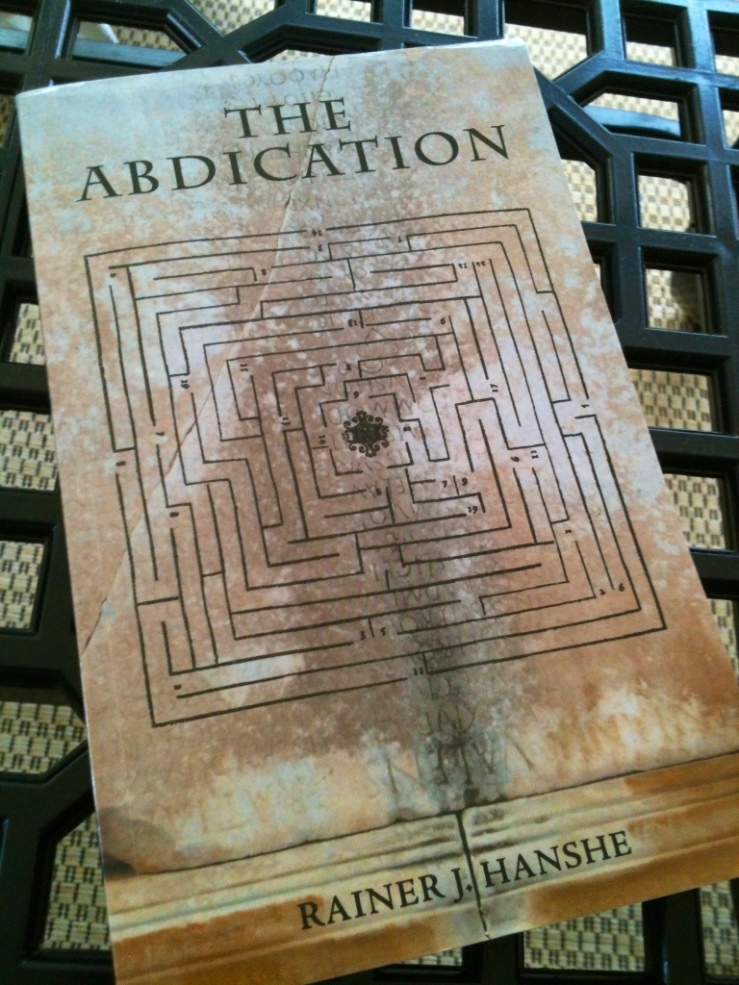

But this post isn’t really about the problem of getting airport novels or gimmick books as gifts. This post is about those of us who insist on giving novels we love to people who we know don’t really love reading novels. Especially really big, somewhat (or very) experimental novels. Important novels. Those novels that we read and decide that everyone needs to read this to become a fully realized human being [gags on that phrase].

I think sometimes we give our friends and relatives novels as gifts because we love them so much and we also love the book so much that we are maybe gunning for an intellectual three-way. We want them to read the novel so that we can share in it together, discuss it, rant about it, argue about it (remember though: that’s what the internet is for).

What often happens though is that these gifted novels (forgive the ambiguous, awkward modifier) tend to lurk about the giftee’s abode, brickishly unread, like dour unwanted houseguests. They skulk at the margins of bookshelves or migrate to the bottom of “to read” stacks; a lucky one might find occasional fingering above a commode. They are ugly reminders to the giftee, signals of how he or she has failed to meet your expectations (your expectations re: 9 or 15 or 25 or 30 hours of her time). (Young people, by which I mean college students in the liberal arts, are the exception here; they probably aren’t going to read the novel, but they are absolutely fine with putting it out for show).

People like books with pictures though, generally.

Even though I think novels tend to make lousy gifts, we should give them to our friends and loved ones anyway, even on those days of obligated giving. We should still offer novels up like they were somehow a part of our own selves in the deluded hope that the giftee will read them and discuss them with us, and that the novel will become an internal, virtual, shared experience. We should give them knowing that it’s likely they’ll go unread, that they may even be a point of shame for the giftee (especially when we ask, “Have you started . . . ?”). We should give them aware that they might point toward our own selfish desires.

Even if a novel may be a gift that implies a certain level of intellectual work, it also implies a sense of trust and respect toward the giftee, and in this sense, giving a loved novel is a clear way to show love.