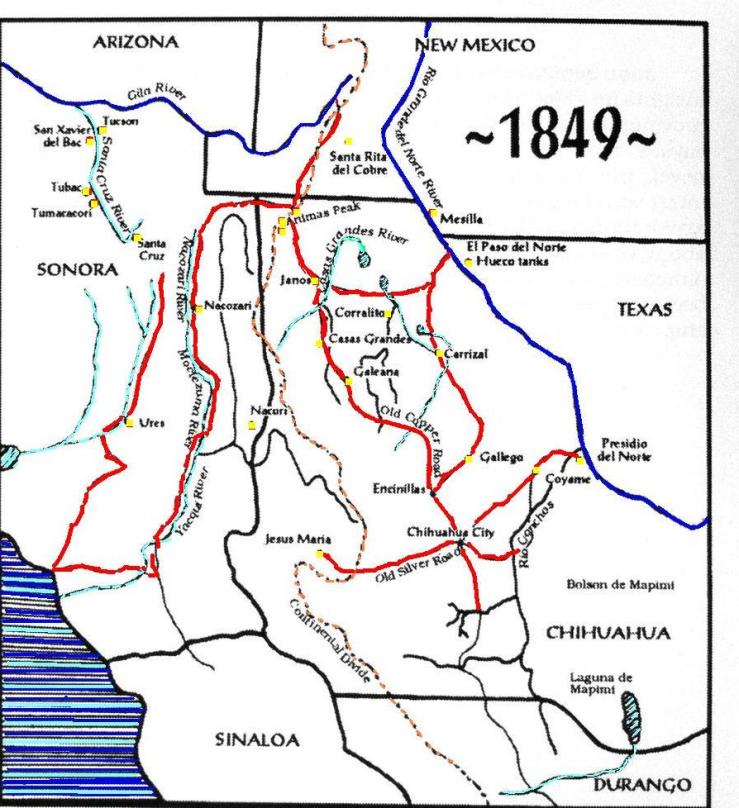

John Sepich created this map of the geographic terrain covered in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian for his companion piece, Notes On Blood Meridian. Blogger The Brooklyn added color.

John Sepich created this map of the geographic terrain covered in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian for his companion piece, Notes On Blood Meridian. Blogger The Brooklyn added color.

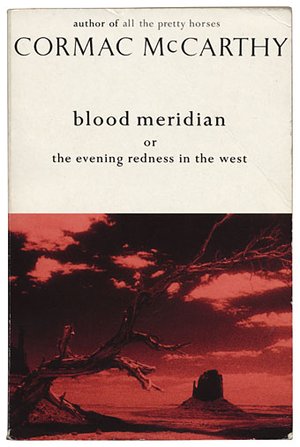

In his 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy said, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” McCarthy’s masterpiece Blood Meridian, as many critics have noted, is made of some of the finest literature out there–the King James Bible, Moby-Dick, Dante’s Inferno, Paradise Lost, Faulkner, and Shakespeare. While Blood Meridian echoes and alludes to these authors and books thematically, structurally, and linguistically, it also owes much of its materiality to Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue.

In his 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy said, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” McCarthy’s masterpiece Blood Meridian, as many critics have noted, is made of some of the finest literature out there–the King James Bible, Moby-Dick, Dante’s Inferno, Paradise Lost, Faulkner, and Shakespeare. While Blood Meridian echoes and alludes to these authors and books thematically, structurally, and linguistically, it also owes much of its materiality to Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue.

Chamberlain, much like the Kid, Blood Meridian’s erstwhile protagonist, ran away from home as a teenager. He joined the Illinois Second Volunteer Regiment and later fought in the Mexican-American War. Confession details Chamberlain’s involvement with John Glanton’s gang of scalp-hunters. The following summary comes from the University of Virginia’s American Studies webpage—

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

Chamberlain’s Confession also describes a figure named Judge Holden. Again, from U of V’s summary–

Glanton’s gang consisted of “Sonorans, Cherokee and Delaware Indians, French Canadians, Texans, Irishmen, a Negro and a full-blooded Comanche,” and when Chamberlain joined them they had gathered thirty-seven scalps and considerable losses from two recent raids (Chamberlain implies that they had just begun their careers as scalp hunters but other sources suggest that they had been engaged in the trade for sometime- regardless there is little specific documentation of their prior activities). Second in command to Glanton was a Texan- Judge Holden. In describing him, Chamberlain claimed, “a cooler blooded villain never went unhung;” Holden was well over six feet, “had a fleshy frame, [and] a dull tallow colored face destitute of hair and all expression” and was well educated in geology and mineralogy, fluent in native dialects, a good musician, and “plum centre” with a firearm. Chamberlain saw him also as a coward who would avoid equal combat if possible but would not hesitate to kill Indians or Mexicans if he had the advantage. Rumors also abounded about atrocities committed in Texas and the Cherokee nation by him under a different name. Before the gang left Frontreras, Chamberlain claims that a ten year old girl was found “foully violated and murdered” with “the mark of a large hand on her throat,” but no one ever directly accused Holden.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

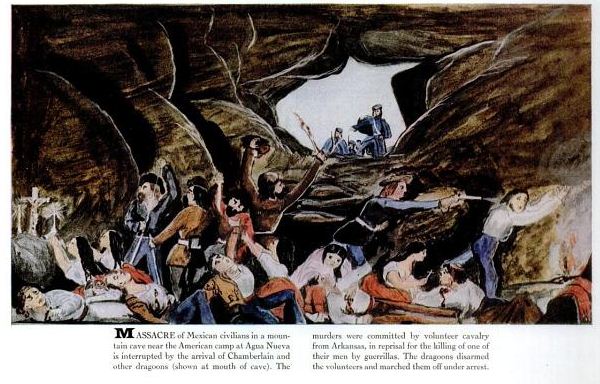

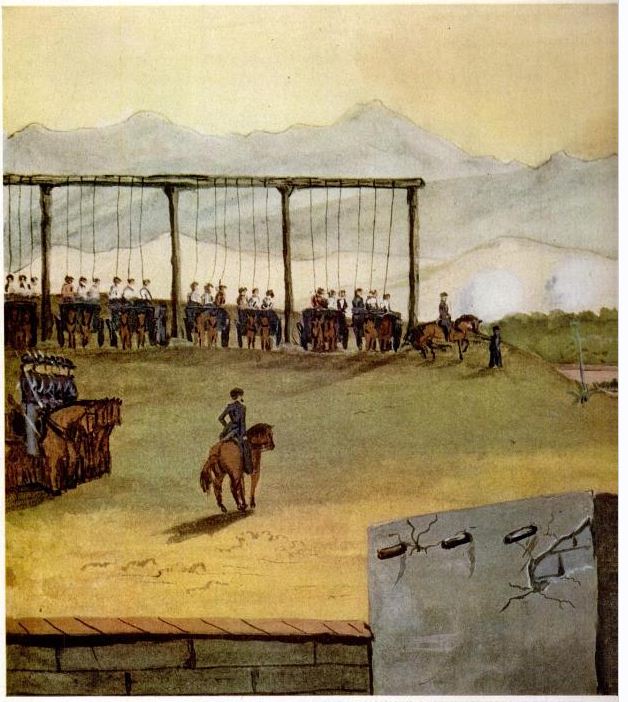

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book Different Travelers, Different Eyes, James H. Maguire notes that, “Both venereal and martial, the gore of [Chamberlain’s] prose evokes Gothic revulsion, while his unschooled art, with its stark architectural angles and leaden, keen-edged shadows, can chill with the surreal horrors of the later Greco-Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.” Yes, Chamberlain was an amateur painter (find his paintings throughout this post), and undoubtedly some of this imagery crept into Blood Meridian.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book Different Travelers, Different Eyes, James H. Maguire notes that, “Both venereal and martial, the gore of [Chamberlain’s] prose evokes Gothic revulsion, while his unschooled art, with its stark architectural angles and leaden, keen-edged shadows, can chill with the surreal horrors of the later Greco-Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.” Yes, Chamberlain was an amateur painter (find his paintings throughout this post), and undoubtedly some of this imagery crept into Blood Meridian.

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s Part I, Part II, and Part III. Many critics have pointed out that Chamberlain’s narrative, beyond its casual racism and sexism, is rife with factual and historical errors. He also apparently indulges in the habit of describing battles and other events in vivid detail, even when there was no way he could have been there. No matter. The ugly fact is that books are made out of books, after all, and if Chamberlain’s Confession traffics in re-appropriating the adventure stories of the day, at least we have Blood Meridian to show for his efforts.

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s Part I, Part II, and Part III. Many critics have pointed out that Chamberlain’s narrative, beyond its casual racism and sexism, is rife with factual and historical errors. He also apparently indulges in the habit of describing battles and other events in vivid detail, even when there was no way he could have been there. No matter. The ugly fact is that books are made out of books, after all, and if Chamberlain’s Confession traffics in re-appropriating the adventure stories of the day, at least we have Blood Meridian to show for his efforts.

Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is larded with strange little pockets of the black humor, humor so black that it’s hard to catch on the first or second reading. Re-reading the book again this week, I was struck by how funny a passage in Chapter XI is. The passage comes immediately after one of the more confounding moments of the book. Judge Holden, the giant, malevolent, Mephistophelean antagonist who dominates the narrative, has just told a puzzling parable about a harness maker who commits a murder and then begs for his son’s forgiveness. It’s a strange story and I’m not sure exactly what it means. Anyway, after he tells this story, Tobin, the ex-priest asks the Judge, “So what is the way of raising a child?” Here’s the reply–

At a young age, said the judge, they should be put in a pit with wild dogs. They should be set to puzzle out from their proper clues the one of three doors that does not harbor wild lions. They should be made to run naked in the desert until…

Hold on now, said Tobin. The questions was put in all earnestness.

And the answer, man, said the judge. If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind, would he not have done so by now? Wolves cull themselves, man. What other creature could? And is the race of man not more predacious yet?

The humor of the Judge’s initial, concrete answer rests on the fact that it is wholly earnest: even in his bizarre, hyperbolic surrealism, the judge is serious. Pits, wild dogs, wild lions. Running naked in the desert. That’s how kids should be raised. The move to the abstract–to highlight humanity’s predatory instincts–is a retreat from humor to philosophy, a pattern that McCarthy repeats in the novel. The effect stuns the impulse to find humor in the language. Humor cannot sustain throughout the narrative, even though it is present.

Dr. Amy Hungerford’s lectures on Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian are part of Yale University’s “Open Yale” series. The lectures were originally presented as part of ENGL 291, The American Novel Since 1945. From the course description–

In this first of two lectures on Blood Meridian, Professor Hungerford walks us through some of the novel’s major sources and influences, showing how McCarthy engages both literary tradition and American history, and indeed questions of origins and originality itself. The Bible, Moby-Dick, Paradise Lost, the poetry of William Wordsworth, and the historical narrative of Sam Chamberlain all contribute to the style and themes of this work that remains, in its own right, a provocative meditation on history, one that explores the very limits of narrative and human potential.

And again–

In this second lecture on Blood Meridian, Professor Hungerford builds a wide-ranging argument about the status of good and evil in the novel from a small detail, the Bible the protagonist carries with him in spite of his illiteracy. This detail is one of many in the text that continually lure us to see the kid in the light of a traditional hero, superior to his surroundings, developing his responses in a familiar narrative structure of growth. McCarthy’s real talent, and his real challenge, Hungerford argues, is in fact to have invoked the moral weight of his sources–biblical, literary, and historical–while emptying them of moral content. Much as the kid holds the Bible an object and not a spiritual guide, McCarthy seizes the material of language–its sound, its cadences–for ambiguous, if ambitious, ends.

David Foster Wallace on Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian: “Don’t even ask.” From his 1999 piece in Salon, “Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels > 1960.”

Biblioklept wants to give you a copy of Random House’s new 25th anniversary edition of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. But you’ll have to earn it because if Blood Meridian teaches us anything (beyond spitting and scalping and riding on), it’s that existence costs. So, if you’d like one to win a handsome new hardback, send us a postcard–the most Blood Meridianish one you can muster. (Do not put blood or anything like blood on the postcard. Seriously). If you’re a fan of the book, include a favorite quote. If you’ve never read it before, let us know why you want to read it. Email us at biblioklept.ed at gmail dot com to get our snail mail address (please make “Blood Meridian contest” the subject of your email). The sender of our favorite postcard will receive a copy of the book, courtesy Biblioklept and Random House. Contest closes October 12, 2010 and is limited to addresses in the continental US.

Biblioklept wants to give you a copy of Random House’s new 25th anniversary edition of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. But you’ll have to earn it because if Blood Meridian teaches us anything (beyond spitting and scalping and riding on), it’s that existence costs. So, if you’d like one to win a handsome new hardback, send us a postcard–the most Blood Meridianish one you can muster. (Do not put blood or anything like blood on the postcard. Seriously). If you’re a fan of the book, include a favorite quote. If you’ve never read it before, let us know why you want to read it. Email us at biblioklept.ed at gmail dot com to get our snail mail address (please make “Blood Meridian contest” the subject of your email). The sender of our favorite postcard will receive a copy of the book, courtesy Biblioklept and Random House. Contest closes October 12, 2010 and is limited to addresses in the continental US.

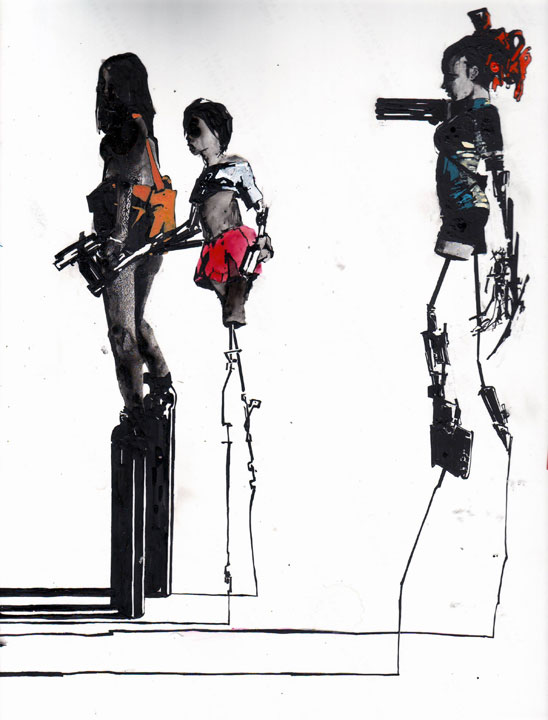

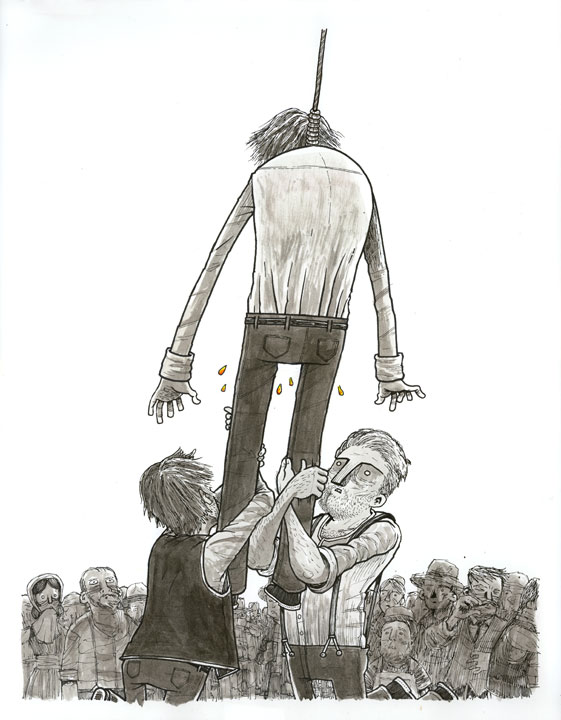

Six Versions of Blood Meridian is an ongoing project where six artists–Zak Smith, Sean McCarthy, John Mejias, Craig Taylor, Shawn Cheng, and Matt Wiegle–illustrate each page of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. Zak Smith’s illustrations are particularly intriguing; he depicts the Glanton gang as women, a strange inversion that for some reason recalls the “Circe/Nighttown” episode of Joyce’s Ulysses. The Six Versions project’s eclectic range of styles and interpretations makes for one of the more fascinating approaches to a contemporary illuminated manuscript that I’ve seen on the internet (I’m also keen on Matt Kish’s handling of Moby-Dick). A few examples–

Critic James Wood wrote extensively about Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian in his 2005 essay for The New Yorker, “Red Planet.” Here’s his lede–

To read Cormac McCarthy is to enter a climate of frustration: a good day is so mysteriously followed by a bad one. McCarthy is a colossally gifted writer, certainly one of the greatest observers of landscape. He is also one of the great hams of American prose, who delights in producing a histrionic rhetoric that brilliantly ventriloquizes the King James Bible, Shakespearean and Jacobean tragedy, Melville, Conrad, and Faulkner.

Wood later details McCarthy’s gift as “one of the greatest observers of landscape”–

“Blood Meridian” is a vast and complex sensorium, at times magnificent and at times melodramatic, but nature is almost always precisely caught and weighed: in the desert, the stars “fall all night in bitter arcs,” and the wolves trot “neat of foot” alongside the horsemen, and the lizards, “their leather chins flat to the cooling rocks,” fend off the world “with thin smiles and eyes like cracked stone plates,” and the grains of sand creep past all night “like armies of lice on the move,” and “the blue cordilleras stood footed in their paler image on the sand like reflections in a lake.”

Wood then goes about attempting to explain his problems with McCarthy the “ham” who produces “histrionic rhetoric” —

[McCarthy’s] prose opens its lungs and bellows majestically, in a concatenation of Melville and Faulkner (though McCarthy always sounds more antique, and thus antiquarian, than either of those admired predecessors). . . .

It is a risky way of writing, and there are times when McCarthy, to my ear, at least, sounds merely theatrical. He has a fondness for what could be called analogical similes, in which the linking phrase “like some” introduces not a visual likeness but a hypothetical and often abstract parallel: “And he went forth stained and stinking like some reeking issue of the incarnate dam of war herself.” . . .

The danger is not just melodrama but imprecision and, occasionally, something close to nonsense. . . .

The inflamed rhetoric of “Blood Meridian” is problematic because it reduces the gap between the diction of the murderous judge and the diction of the narration itself: both speak with mythic afflatus. “Blood Meridian” comes to seem like a novel without internal borders.

So, Blood Meridian doesn’t meet the standard of Wood’s cherished “free indirect style,” where an author subtly shifts into a character’s voice. Wood craves these delicate internal borders. He can’t bear the idea that the towering figure of Judge Holden might come to ventriloquize the novel. It is worth noting here that Wood frequently extols the free indirect styles of Marcel Proust and Henry James–two authors McCarthy dismissed in a 1992 interview with The New York Times, saying “I don’t understand them . . . that’s not literature.” Wood values a mannered precision of realism that McCarthy openly professes little interest in; rather, McCarthy uses a mythic, amplified, and at times grandiose style in Blood Meridian to explore issues of life and death. And Wood is perhaps not wrong here. At times Blood Meridian edges into bombast, although I believe McCarthy controls his language more than Wood allows. In either case, McCarthy’s language is ripe for parody, as exemplified in this clip from Wes Anderson’s 2001 film The Royal Tenenbaums—

I would be happy to leave Wood’s criticism of Blood Meridian and McCarthy alone at this point. Fine, Wood doesn’t like it when McCarthy goes balls-to-the-wall; whatever. But at the end of “Red Planet” Wood turns to attacking McCarthy’s perceived failure to vindicate God’s goodness in the face of evil. Wood here (and elsewhere, always elsewhere) shows his deep conservatism. Wood necessitates that all literature reveal a platonic center, a stable, beating heart that must also be a platonic good. Here he is, griping about McCarthy’s “metaphysical cheapness”–

Like most writers committed to pessimism, McCarthy is never very far from theodicy. Relentless pain, relentlessly displayed, has a way of provoking metaphysical complaint. . . .

But McCarthy stifles the question of theodicy before it can really speak. His myth of eternal violence—his vision of men “invested with a purpose whose origins were antecedent to them”—asserts, in effect, that rebellion is pointless because this is how it will always be. Instead of suffering, there is represented violence; instead of struggle, death; instead of lament, blood.

If Wood finds only a nihilism in Blood Meridian (and the rest of McCarthy’s oeuvre) that he fundamentally disagrees with, he should simply say so. Instead, Wood demands that Blood Meridian be a theodicy and then condemns it for not being one. He shamefully attempts to hold the work to a radically subjective rubric that cannot be answered. Put another way, the failure that Wood finds in Blood Meridian is a failure to answer to a version of God–and God’s judgment–that Wood would like to believe in (or, more accurately, be comforted by).

Wood is a bully (of both authors and readers) whose criticisms rarely enlarge the works they seek to address. We see his program at work in “Red Planet,” where his aim is to deflate Blood Meridian’s giant language and not appraise it on its own terms. That the book survives–and thrives–despite Wood’s criticism is hardly surprising; that a critical conversation of Blood Meridian should include Wood is depressing.

Blood Meridian is a blood-soaked, bloodthirsty bastard of a book, and certainly the most violent piece of literature I’ve read outside of the Bible and certain Greek tragedies. Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel passes itself off as a Western–and it is a Western, to be sure–but more than anything, it’s a brutal horror story.

Set predominantly in the 1850s, Blood Meridian chronicles the westward journey of a protagonist we know only as “the kid.” After a few false starts (including getting shot, robbed, arrested, and surviving a Comanche massacre) the kid eventually meets up with John Joel Glanton‘s “expedition”–a group of men of mixed backgrounds hired by Mexican authorities to kill–and scalp–the nomadic Apache who prey upon Mexican villages. However, led by the nefarious, larger-than-life Judge Holden, Glanton’s gang quickly descends into a relentless robbing, raping, and killing spree; they savagely massacre peaceful Indian settlements along with the Mexican villages they were contracted to protect.

I could keep summarizing the book, but I don’t see the point, honestly–a mere description of the plot could never do real justice to the weight of this book. The narrative is taut and fast-paced–in fact, at points the action is so radically condensed that I had to go back and re-read sections–and there’s no shortage of the “men doing men stuff” that McCarthy is so good at detailing–but it’s really the combination of the book’s evocative imagery and philosophical pondering that hook the reader.

Most of that philosophical pondering comes from the Judge, who waxes heavy on everything from space aliens to metallurgy. In his parables and aphorisms, the Judge comes across as part-Mephistophelean, part-Nietzschean, all dark wisdom and irreverent chaos. I found myself re-reading the Judge’s speeches several times and chewing them over, trying to digest them; for me, they were the best part of a great book.

Blood Meridian, like most excellent things, is simply not for everyone, and I don’t mean that in any snobbish, elitist sense. Any reader turned off by its freewheeling violence would be justified, and I’m sure plenty of folks out there would take issue with its ambiguous conclusion. Depictions of genocidal mania that seem to end inconclusively are not for everyone, particularly when they are rife with archaisms, untranslated Spanish, and McCarthy’s signature apostrophe-free punctuation. I had two false starts with the novel, including one where, at about exactly half way through, I realized I had to go back and start the novel again. I owed it that much. And it was worth it.

Blood Meridian is literally stunning; perhaps the best analogy I can think of is going to see a really, really good band that plays really, really brutal and strange music that sorta melts your face off. After the show you’re sweaty and exhilarated and even unnerved; your ears are ringing and your chest is pounding. And then the band packs up, and the house lights go on, and they pump in music from a CD, of all things, and the music just sounds tinny and pale and blanched of life after the raw power you’ve witnessed. Reading anything else right after finishing Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West is sort of like that. Highly recommended.

[Editorial note–Biblioklept originally published this review on April 6th, 2008. We’re running it again as part of a week of coverage celebrating Blood Meridian’s 25th anniversary].

This week, Random House celebrates the 25th anniversary of Cormac McCarthy’s masterpiece Blood Meridian by releasing a new hardback edition of the book. This new Modern Library version retains Harold Bloom’s now-oft-cited introductory essay and features a new cover design by Richard Adelson that echoes the first edition and restores its original art work, The Phantom Cart by Salvador Dali. Here is the new cover–

The release of this new edition and the book’s anniversary give us a great excuse to declare the next five days Blood Meridian Week on Biblioklept. (Yes, we know that it’s also Banned Books Week this week. But celebrating Blood Meridian seems to gel with that). We’ll re-run our original review, take a look at what different critics have had to say about the book, quote some of our favorite passages at length, share some of the better resources at large for tackling this often difficult book, examine some of the history behind it, and generally laud it for its horrifying excellence. We’ll also be giving away a copy of the new 25th anniversary edition to one lucky reader, so keep your eyes peeled for details.

Welcome to Biblioklept’s 777th Post Spectacular*

*Not guaranteed to be spectacular.

777 seems like a beautiful enough number to celebrate, and because we’re terribly lazy, let’s celebrate by sharing reviews of seven of our favorite novels that have been published since this blog started back in the hoary yesteryear of 2006. In (more or less) chronological order–

The Children’s Hospital–Chris Adrian — A post-apocalyptic love boat with metaphysical overtones, Adrian’s end of the world novel remains underrated and under-read.

The Road — Cormac McCarthy — That ending gets me every time. The first ending, I mean, the real one, the one between the father and son, not the tacked on wish-fulfillment fantasy after it. Avoid the movie.

A Mercy — Toni Morrison –Slender and profound, A Mercy should be required reading for all students of American history. Or maybe just all Americans.

Tree of Smoke — Denis Johnson — Nobody knew we needed another novel about the Vietnam War and then Johnson went and showed us that we did. But it’s fair to say his book is about more than that; it’s an espionage thriller about the human soul.

2666 — Roberto Bolaño — How did he do it? Maybe it was because he was dying, his life-force transferred to the page. Words as viscera. God, the blood of the thing. 2666 is both the labyrinth and the minotaur.

Asterios Polyp — David Mazzucchelli — We laughed, we cried, and oh god that ending, right? Wait, you haven’t read Asterios Polyp yet? Is that because it’s a graphic novel, a, gasp, comic book? Go get it. Read it. Come back. We’ll wait.

C — Tom McCarthy — Too much has been made over whether McCarthy’s newest novel (out in the States next week) is modernist or Modernist or post-modernist or avant-garde or whatever–these are dreadfully boring arguments when stacked against the book itself, which is complex, rich, enriching, maddening.

From Burt Britton’s collection of self-portraits, um, Self-portrait. McSweeney’s 34 has taken the work as inspiration. See a full gallery here, including portraits from Jorge Luis Borges, Maurice Sendak, and Margaret Atwood, among others. This goofy Cormac McCarthy self-portrait is priceless, especially from a guy famous for images of trees hanging with dead babies.

In a 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy famously said that he only cares for writers who “deal with issues of life and death.” He disses Proust and Henry James, saying “I don’t understand them . . . that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange.” Because he has granted so few interviews–and come off so guarded in those he has done–McCarthy’s dictum on “good writers” has perhaps become a bit inflated, elevated from one man’s opinion to a grand litmus test of literary worth. Still, I often find myself putting the books I read under the McCarthy stress-test: do they narrativize the Darwinian drama of life and death? Or are they simply bloodless spectacles of rhetoric, ephemeral social critiques, or faddish forays into solipsism? McCarthy’s targets, Proust and James, arguably do address life and death issues in their works, but when compared to McCarthy’s heroes–Melville, Faulkner, Dostoevsky–the social fictions of Proust and James seem wan, or at least too subtle and overly-coded. The two novels I’m currently working through, Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City and Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone, illustrate not just the poles of McCarthy’s dichotomy, but also why many readers (myself included) tend to prefer that their novels address matters of life and death.

Every Man Dies Alone, first published in German in 1947, is available for the first time ever in English, thanks to translator Michael Hoffman (if you’ve read Kafka in English, you’ve probably read Hoffman’s work) and the good folks at Melville House. Fallada’s novel tells the story of German resistance to the Nazi regime, not at an aristocratic or militaristic level (this isn’t Valkyrie), or even a literary or philosophical level, but at the level of every day, ordinary existence. After the death of their son in battle, Otto and Anna Quangel initiate a campaign of resistance to the Nazi party, one that is of course doomed from the outset. The Quangels soon involve Eva Kluge, among others, in their covert resistance cell. Kluge is a letter-carrier who becomes disgusted with the moral implications of the regime; she’s also deeply embittered by the way Nazi rule has systemically destroyed her family. Kluge’s peripatetic job helps to enact Fallada’s major rhetorical gesture, a sweeping busyness that vividly recreates the life of ordinary Germans during the rule of the Third Reich. We might begin in Kluge’s mind as she embarks to deliver a letter, only to find ourselves awash in the thoughts of its recipient a few pages later. Fallada’s omniscient third-person narrator moves freely from one character’s consciousness to another’s, shifting fluidly from the immediacy of present tense to the solidity of past tense. It’s modernism (whatever that means)–Tolstoy without the rich and famous, Joyce without the mythos and erudition, but deeply engaging in its scope. WWII has produced a seemingly endless myriad of narratives, yet Fallada’s tome is the first that I’ve experienced of its kind. Perhaps its subject matter–the lives of ordinary Germans and their unsuccessful attempts to resist the mundane evil all around them–is simply not the stuff that we want from our war stories, and perhaps this is why the book has been absent so long from an English translation. It’s evocative of a world that I had never really considered before: after all, the narrative of WWII is far easier to comprehend if you retain the simplicity of the good guys (the Allies), the bad guys (the Nazis), and the victims (the Jewish population of Europe). Ordinary Germans have only one place in this uncomplicated system, which is why the story of the Quangels and their cohort is so profound (oh, the Quangels are based on the real-life Nazi resisters Otto and Elise Hampel, if you must know). Driven in part by despair, they seek to forge meaning in their lives, even if its at the cost of death, or the horrors of a concentration camp. To return to McCarthy’s caveat, Fallada’s novel is a work that dramatizes life and death against a decidedly unheroic backdrop, a novel that makes its reader repeatedly ask himself whether or not he would be, to use another McCarthyism (from The Road) one of the “good guys.” Great stuff, and so far one of the better novels we’ve read this year. Go get it.

It’s perhaps unfair to lump Lethem’s latest in a review with Fallada, given the historical complexity of Every Man Dies Alone‘s milieu. Still, I’ve been reading my review copies of both novels over this long weekend, trying to catch up, and I find that I would almost always rather pick up Fallada’s book. It compels me, whereas, half way through Chronic City, I still find nothing to care about, no risk, no cost, no guts. No matters of life and death. The novel centers around former-child actor Chase Insteadman, whose directionless existence seems to thematically underpin the book. Chase moves from party to party in a fictitious Manhattan, charming various socialites and keeping boredom (marginally) at bay. He soon hooks up with Perkus Tooth, a marijuana-addicted pop culture critic, whose characteristics will be familiar to pretty much anyone who earned a liberal arts degree in college. Tooth seems to function largely as a mouthpiece for Lethem to espouse various opinions on movies and books and art. It’s a clumsy device as it doesn’t shade the character–it’s simply Lethem couching his cultural criticism in the comfort of a work of fiction. In a particularly telling scene, Perkus picks up a copy of The New York Times and thinks that it feels too light. He looks up at the right-hand corner: “WAR FREE EDITION. Ah yes, he’d heard about this. You could opt out now.” Perkus seems to deliver the line as a criticism, but it’s Lethem who’s opting out. He drops hints of destruction and annihilation and disintegration in the novel–there’s a giant tiger on the loose somewhere in Manhattan; Chase’s fiancée floats estranged in space, stranded on the International Space Station; a crooked mayor is up to dastardly shenanigans–but Lethem protects his characters from it all in an insulating cocoon of marijuana smoke and pop trivia. Their forays into the darkness of Manhattan’s mysteries are meant to play both humorously but also with enough danger to fully invest a reader’s attention (think of Lethem’s more successful sci-noir Gun, with Occasional Music, or his detective thriller Motherless Brooklyn). Instead, the adventures fall flat, collapsing back into Perkus’s apartment, a vortex of (ultimately meaningless) pop culture. While the novel is by no means terrible–it’s well-written, of course–there is simply a tremendous lack of the “life and death” stuff that McCarthy–and other readers–require. In short–and in contrast with Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone–it does not compel itself to be read. Which is a shame of course. I still think Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude was one of the finest books of the decade, and I was deeply disappointed in his last novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Chronic City is a much finer book than that silly train wreck, but it lacks the urgency of Lethem’s finest works, Fortress and Motherless Brooklyn, which temper a love of popular culture with genuine characters and an affecting plot.

I’ll conclude by returning to Cormac McCarthy, this time to his latest interview (in The Wall Street Journal). He says, on writing novels: “Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.” And later: “Creative work is often driven by pain. It may be that if you don’t have something in the back of your head driving you nuts, you may not do anything.” For McCarthy, literature, in its final product–the reader reading the book–is the direct communication of the pain of creation, the awkward and incomplete translation of ideas exchanged from author to audience. Perhaps the pain was too much for Fallada, who died in 1947 of a morphine overdose, but that pain–that spirit–exists in the book. A similar spirit exists in Lethem’s earlier works; I’d love to see him tap into it again in his next venture.

Every Man Dies Alone is now available in hardback from Melville House.

Chronic City is now available in hardback from Double Day.

We often identify genre simply by its conventions and tropes, and, when October rolls round and we want scary stories, we look for vampires and haunted houses and psycho killers and such. And while there’s plenty of great stuff that adheres to the standard conventions of horror (Lovecraft and Poe come immediately to mind) let’s not overlook novels that offer horror just as keen as any genre exercise. We offer seven horror novels masquerading in other genres:

Blood Meridian — Cormac McCarthy

In our review (link above) we called Blood Meridian “a blood-soaked, bloodthirsty bastard of a book.” The story of the Glanton gang’s insane rampage across Mexico and the American Southwest in the 1850s is pure horror. Rape, scalping, dead mules, etc. And Judge Holden. . . [shivers].

Rushing to Paradise — J.G. Ballard

On the surface, Ballard’s 1994 novel Rushing to Paradise seems to be a parable about the hubris of ecological extremism that would eliminate humanity from any natural equation. Dr. Barbara and her band of misfit environmentalists try to “save” the island of St. Esprit from France’s nuclear tests. The group eventually begin living in a cult-like society with Dr. Barbara as its psycho-shaman center. As Dr. Barbara’s anti-humanism comes to outweigh any other value, the island devolves into Lord of the Flies insanity. Wait, should Lord of the Flies be on this list?

Okay. We know. This book ends up on every list we write. What can we do?

While there’s humor and pathos and love and redemption in Bolaño’s masterwork, the longest section of the book, “The Part about the Crimes,” is an unrelenting catalog of vile rapes, murders, and mutilations that remain unresolved. The sinister foreboding of 2666‘s narrative heart overlaps into all of its sections (as well as other Bolaño books); part of the tension in the book–and what makes Bolaño such a gifted writer–is the visceral tension we experience when reading even the simplest incidents. In the world of 2666, a banal episode like checking into a motel or checking the answering machine becomes loaded with Lynchian dread. Great horrific stuff.

King Lear — William Shakespeare

Macbeth gets all the propers as Shakespeare’s great work of terror (and surely it deserves them). But Lear doesn’t need to dip into the stock and store of the supernatural to achieve its horror. Instead, Shakespeare crafts his terror at the familial level. What would you do if your ungrateful kids humiliated you and left you homeless on the heath? Go a little crazy, perhaps? And while Lear’s daughters Goneril and Regan are pure mean evil, few characters in Shakespeare’s oeuvre are as crafty and conniving as Edmund, the bastard son of Glouscester. And, lest we forget to mention, Lear features shit-eating, self-mutilation, a grisly tableaux of corpses, and an eye-gouging accompanied by one of the Bard’s most enduring lines: “Out vile jelly!” Peter Brook chooses to elide the gore in his staging of that infamous scene:

The Trial — Franz Kafka

Kafka captured the essential alienation of the modern world so well that we not only awarded him his own adjective, we also tend to forget how scary his stories are in light, perhaps, of their absurd familiarity. For our money, none surpasses his unfinished novel The Trial, the story of hapless Josef K., a bank clerk arrested by unknown agents for an unspecified crime. While much of K.’s attempt to figure out just who is charging him for what is hilarious in its absurdity, its also deeply dark and really creepy. K. attempts to find some measure of agency in his life, but is ultimately thwarted by forces he can’t comprehend–or even see for that matter. Nowhere is this best expressed than in the famous “Before the Law” episode. If you’re too lazy to read it, check out his animation with narration by the incomparable Orson Welles:

In our original review of Sanctuary (link above), we noted that “if you’re into elliptical and confusing depictions of violence, drunken debauchery, creepy voyeurism, and post-lynching sodomy, Sanctuary just might be the book for you.” There’s also a corn-cob rape scene. The novel is about the kidnapping and debauching of Southern belle Temple Drake by the creepy gangster Popeye–and her (maybe) loving every minute of it. The book is totally gross. We got off to a slow start with Faulkner. If you take the time to read our full review above (in which we make some unkind claims) please check out our retraction. In retrospect, Sanctuary is a proto-Lynchian creepfest, and one of the few books we’ve read that has conveyed a total (and nihilistic) sense of ickyness.

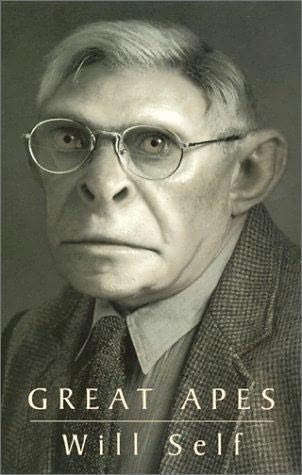

Great Apes — Will Self

Speaking of ickiness…Self’s 1997 novel Great Apes made me totally sick. Nothing repulses me more than images of chimpanzees dressed as humans and Great Apes is the literary equivalent (just look at that cover). After a night of binging on coke and ecstasy, artist Simon Dykes wakes up to find himself in a world where humans and apes have switched roles. Psychoanalysis ensues. While the novel is in part a lovely satire of emerging 21st-century mores, its humor doesn’t outweigh its nightmare grotesquerie. Great Apes so deeply affected us that we haven’t read any of Self’s work since.

In Cormac McCarthy‘s second novel, Outer Dark, set in the backwoods and dust roads of turn-of-the-century Appalachia, Culla Holme hunts his sister Rinthy, who has abandoned the pair’s shack to find her newborn baby. Culla has precipitated this journey by abandoning the infant in the woods to die; a wandering tinker finds the poor child and absconds with it. As Rinthy and Culla independently scour the bleak countryside on their respective quests, a band of killers led by a Luciferian figure roams the wilderness, wreaking violence and horror wherever they go.

In a recent interview with the AV Club, critic Harold Bloom noted that Cormac McCarthy “tends to carry his influences on the surface,” pointing out that McCarthy’s major influence, William Faulkner, tends to proliferate throughout McCarthy’s early work to such an extent that those works (The Orchard Keeper, Outer Dark, Child of God, Suttree) suffer to a certain degree. Indeed, it’s hard not to read Outer Dark without the Faulkner comparison invading one’s perception. It’s not just McCarthy’s Appalachian milieu, populated with Southern Gothicisms, hideous grotesques, rural poverty, incest, and a general queasiness. It’s also McCarthy’s Faulknerian rhetoric, his elliptical syntax, his dense, obscure diction, his bricks of winding language that seem to obfuscate and resist easy interpretation. Like Faulkner, McCarthy’s language in Outer Dark functions as a dare to the reader, a challenge to venture to the limits of what words might mean when compounded. And while the results are sometimes (literally) startling, they often strain, if not outright break, the basic contract between writer and reader: at times, all cognitive sense is lost in the word labyrinth. Take the following sentence that ends the first chapter, where Culla looks back on the infant he has just abandoned:

It howled execration upon the dim camarine world of its nativity wail on wail while lay there gibbering with palsied jawhasps, his hands putting back the night like some witless paraclete beleaguered with all limbo’s clamor.

A “paraclete” is someone who offers comfort, an advocate. I’m thinking that the “jawhasps” must be a twisted mouth. No idea what “camarine” means. But it’s not just the obscure diction here: the whole action is obscure (how does one go about “putting back the night”?). This confusing passage is hardly an isolated incident in Outer Dark; instead McCarthy repeatedly employs long, dense, nearly unintelligible sentences, constructions that defy the reader’s ability to visualize the words he or she is being asked to decode. This unfortunate tendency alienates the reader in ways that are no doubt intentional, yet ultimately unproductive. More often than not, McCarthy’s long twisting hydras of obscurantism are not so much moving or thought-provoking as they are laughably ridiculous, and while his vocabulary is surely immense, it’s hard enough to get through such abstract sentences without having to run to a dictionary every other word.

Readers of mid-period, or even more recent McCarthy works will no doubt recognize this complaint, so it’s important to note that we’re not talking about the density and alienating syntax of Blood Meridian, the philosophical pontificating of The Border Trilogy, or the occasional run-to-a-thesaurus word choice one can find in The Road. No, Outer Dark is full-blown Faulkner-aping (Faulkner at his worst, I should add); over-written, ungenerous, and just generally hard to get into, especially the early part of the novel which is particularly guilty of these crimes. Which is a shame, because once one penetrates the wordy exterior of the first few chapters, there’s actually a pretty good novel there. While no one could accuse Outer Dark of having a tight, gripping plot, the intertwined tales of Culla and Rinthy–and the band of outlaws–gives McCarthy an excellent venue to showcase his biggest strength in the novel–the dialogue.

Spare and terse, the strange, strained conversations between McCarthy’s Appalachian grotesques are often funny, usually tense, and always awkward. Culla and Rinthy are outcasts who don’t quite understand the extent of their estrangement from the dominant social order. They frequently encounter fellow outcasts, often freaks of a mystical persuasion, like the witchy old woman who frightens Rinthy, or the old snake-trapper who freaks out Culla (a task not easily achieved). The dialogue between McCarthy’s characters reads with authenticity and intensity, and the author gets far more mileage out of the gaps in conversation, the elisions, the omissions–what is not said, what cannot be said. These odd characters culminate in the trio of outlaws who terrorize the fringes of Outer Dark. Their ominous black-clad leader prefigures many of McCarthy’s later antagonists, like the Judge of Blood Meridian or Chigurh in No Country for Old Men, but he pales in comparison to the former’s eloquent anarchy and the latter’s bloody intensity. McCarthy doesn’t really seem to know what to do with him, to tell the truth. Still, fans of Chigurh and the Judge will find the roots of those characters in this unnamed villain, and will probably have some interest in McCarthy’s evolution of this type.Indeed, it’s tracking this progression of themes and types throughout McCarthy’s body of work that was of the greatest interest to me, and in turn, I suspect that Outer Dark is probably going to be of greatest interest to those who’ve been reading McCarthy more or less chronologically backwards (like I have). It’s certainly not the starting place for this gifted author, and while its early dense prose will certainly provoke a few mournful groans, the end of the book redeems the bog of language at its outset.

Literature seems to have an ambivalence toward fatherhood that’s too complex to address in a simple blog post–so I won’t even try. But before I riff on a few of my favorite fathers from a few of my favorite books, I think it’s worth pointing out how rare biological fathers of depth and complexity are in literature. That’s a huge general statement, I’m sure, and I welcome counterexamples, of course, but it seems like relationships between fathers and their children are somehow usually deferred, deflected, or represented in a shallow fashion. Perhaps it’s because we like our heroes to be orphans (whether it’s Moses or Harry Potter, Oliver Twist or Peter Parker) that literature tends to eschew biological fathers in favor of father figures (think of Leopold Bloom supplanting Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses, or Merlin taking over Uther Pendragon‘s paternal duties in the Arthur legends). At other times, the father is simply not present in the same narrative as his son or daughter (think of Telemachus and brave Odysseus, or Holden Caulfield wandering New York free from fatherly guidance). What I’ve tried to do below is provide examples of father-child relationships drawn with psychological and thematic depth; or, to put it another way, here are some fathers who actually have relationships with their kids.

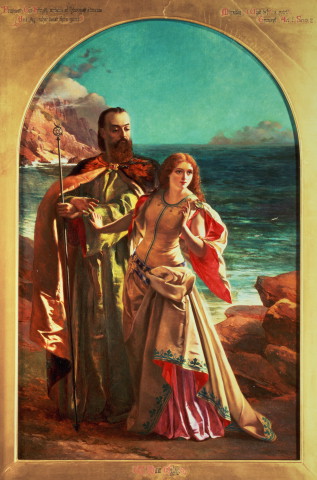

1. Prospero, The Tempest (William Shakespeare)

Prospero has always seemed to me the shining flipside to King Lear’s dark coin, a powerful sorcerer who reverses his exile and is gracious even in his revenge. Where Lear is destroyed by his scheming daughters (and his inability to connect to truehearted Cordelia), Prospero, a single dad, protects his Miranda and even secures her a worthy suitor. Postcolonial studies aside, The Tempest is fun stuff.

2. Abraham Ebdus, The Fortress of Solitude, (Jonathan Lethem)

Like Prospero, Abraham Ebdus is a single father raising his child (his son Dylan) in an isolated, alienating place (not a desert island, but 1970’s Brooklyn). After Dylan’s mother abandons the family, the pair’s relationship begins to strain; Lethem captures this process in all its awkward pain with a poignancy that never even verges on schlock. The novel’s redemptive arc is ultimately figured in the reconciliation between father and son in a beautiful ending that Lethem, the reader, and the characters all earn.

3. Jack Gladney, White Noise (Don DeLillo)

While Jack Gladney is an intellectual academic, an expert in the unlikely field of “Hitler studies” (and something of a fraud, to boot), he’s also a pretty normal dad. Casual reviewers of White Noise tend to overlook the sublime banality of domesticity represented in DeLillo’s signature novel: Gladney is an excellent father to his many kids and step-kids, and DeLillo draws their relationships with a realism that belies–and perhaps helps to create–the novel’s satirical bent.

4. Oscar Amalfitano, 2666 (Roberto Bolaño)

Sure, philosophy professor Amalfitano is a bit mentally unhinged (okay, more than a bit), but what sane citizen of Santa Teresa wouldn’t go crazy, what with all the horrific unsolved murders? After his wife leaves him and their young daughter, Amalfitano takes them to the strange, alienating land of Northern Mexico (shades of Prospero’s island?) Bolaño portrays Amalfitano’s descent into paranoia (and perhaps madness) from a number of angles (he and his daughter show up in three of 2666‘s three sections), and as the novel progresses, the reader slowly begins to grasp the enormity of the evil that Amalfitano is confronting (or, more realistically, is unable to confront directly), and the extreme yet vague danger his daughter is encountering. Only a writer of Bolaño’s tremendous gift could make such a chilling episode simultaneously nerve-wracking, philosophical, and strangely hilarious.

5. The father, The Road (Cormac McCarthy)

What happens when Prospero’s desert island is just one big desert? If there is a deeper expression of the empathy and bonding between a child and parent, I have not read it. In The Road, McCarthy dramatizes fatherhood in apocalyptic terms, positing the necessity of such a relationship in hard, concrete, life and death terms. When the father tells his son “You are the best guy” I pretty much break down. When I first read The Road, I had just become a father myself (my child was only a few days old when I finished it), yet I was still critical of McCarthy’s ending, which affords a second chance for the son. It seemed to me at the time–as it does now–that the logic McCarthy establishes in his novel is utterly infanticidal, that the boy must die, but I understand now why McCarthy would have him live–why McCarthy has to let him live. Someone has to carry the fire.