For the past few days I’ve felt as if I would never put one word after another again, that I would never put together a sentence, string together clauses and sling them out into the world. This previous statement is hyperbole and I am silly—but even simple emails have seemed the acme of wretched futility to compose. Chalk it up to a mild head cold; chalk it up to too many essays to grade; chalk it up to anxiety of (fear of) writing. But I feel like I used to want to feel like I needed to write, right? On 1 Oct. 2018 I wrote a silly post on this weblog called “Blog about October reading (and blogging) goals,” in which I set a goal to blog “every day, even about nothing,” which I failed to achieve.

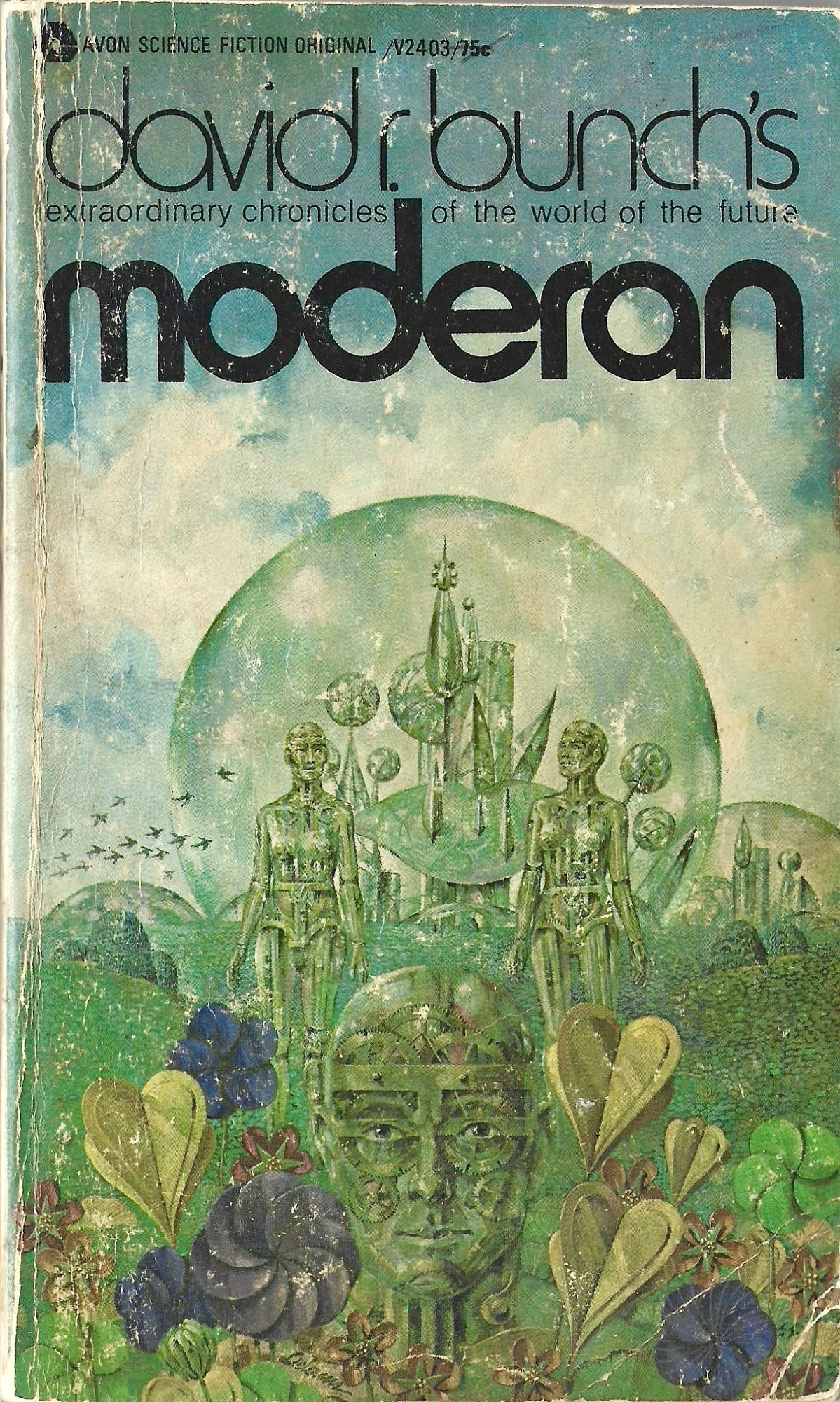

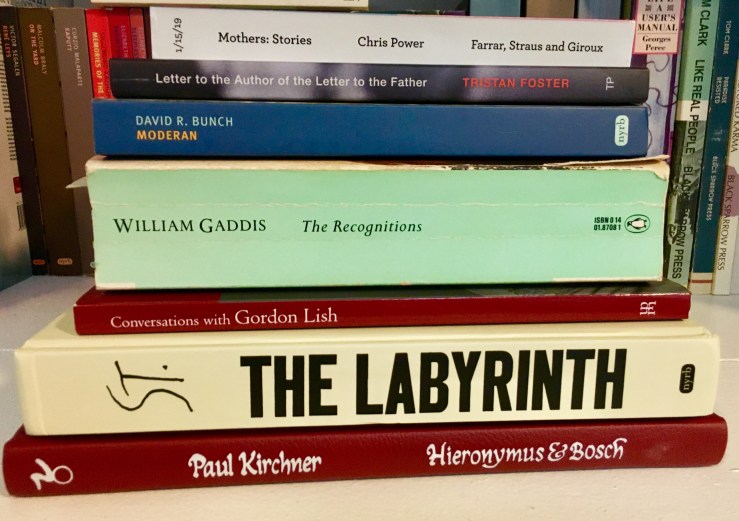

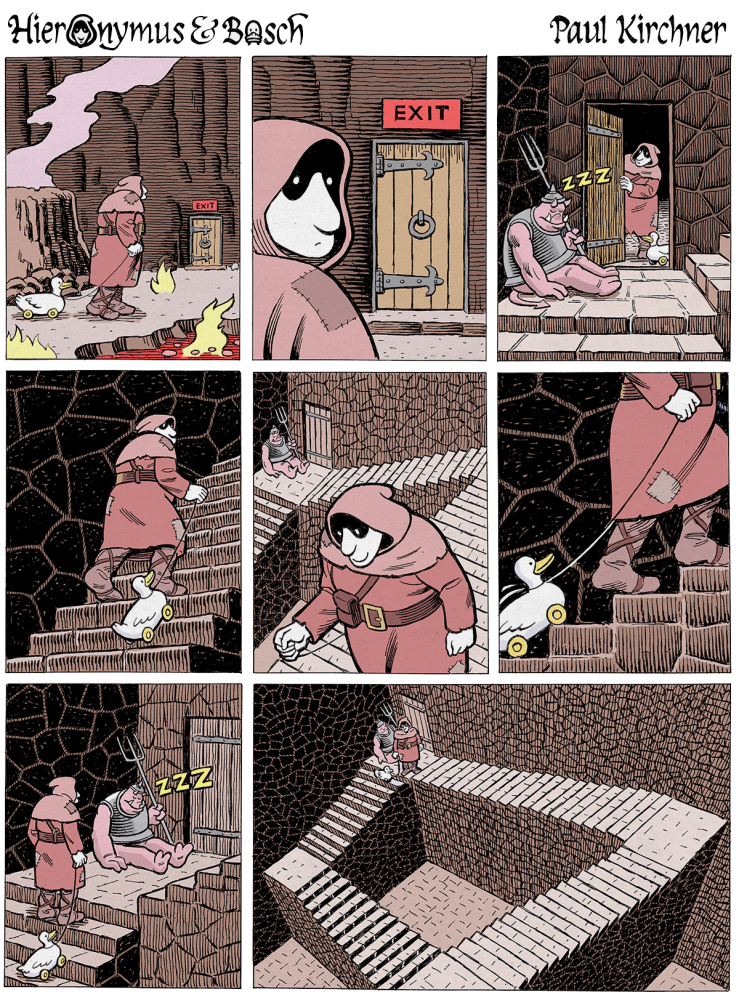

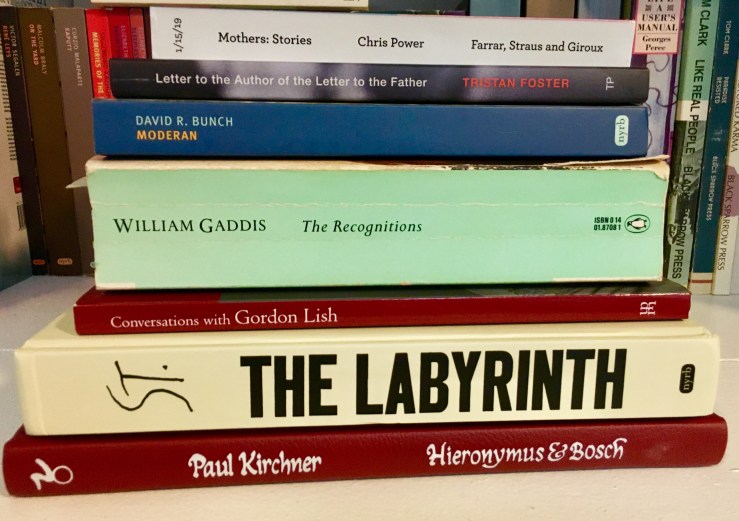

I did actually achieve some of the reading goals expressed in that October goals blog though: I finished George Eliot’s Silas Marner; I made a bigger dent in Moderan, David R. Bunch’s cult dystopian novel; I finally read William Gaddis’s novel Carpenter’s Gothic; I actually returned and did not keep forever a book I borrowed from a friend; I did not gobble up Paul Kirchner’s Hieronymus & Bosch but rather limited myself to one or two cartoon strips a day (or sometimes, like, five).

So for November—

I’ve read the first two stories in Chris Power’s debut collection Mothers and they are good (the collection is available in the US in January 2019; I should have a full review then).

Tristan Foster’s collection Letter to the Author of the Letter to the Father is very much my weird cup of weird tea.

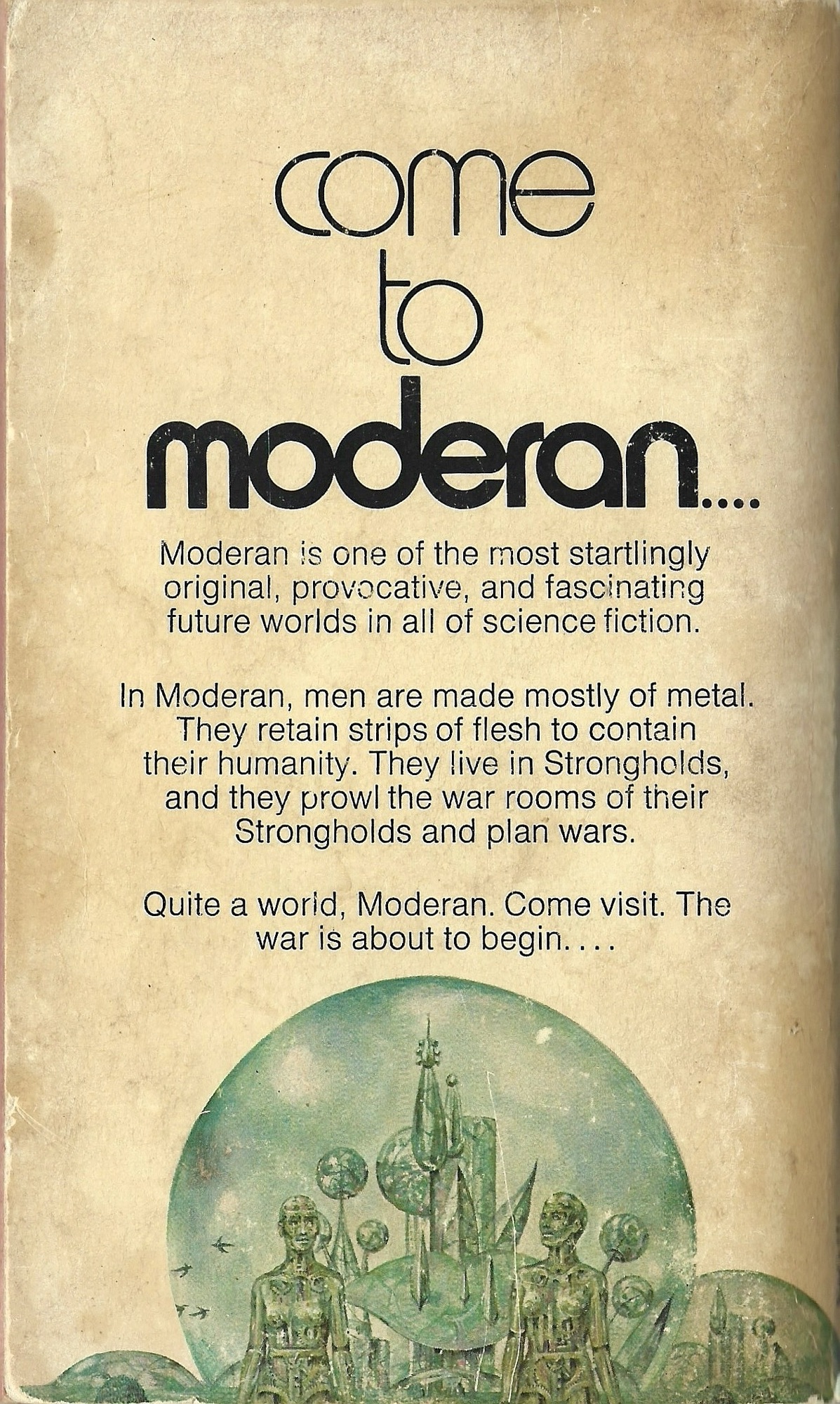

David Bunch’s Moderan deserves a big proper essay. I’ve suggested that our zeitgeist surpasses the parodic powers of postmodernism’s toolkit, but Moderan anticipates and slices up Our Bad Times.

Part of my anxiety about writing comes from having failed three times now to write a proper review of Conversations with Gordon Lish, which is the kind of self-deconstructing performance of writing about writing that is difficult to describe or analyze; it’s the sort of thing you simply want the reader to read.

I started the audiobook of William Gaddis’s novel The Recognitions, and have ended up not only reading my Penguin edition in tandem—a sort of re-rereading—but have also been flirting with The Gaddis Tapes1 and Letters of William Gaddis. (This summer I said I’d reread The Recognitions: is this that?). I don’t really know what I want from this material, and I certainly don’t suggest it as anything approaching ancillary or auxiliary “help” with Gaddis’s project—I mean, in his Paris Review interview Gaddis paraphrases his hero and explains why we shouldn’t look for keys to art in the artist:

I’d go back to The Recognitions where Wyatt asks what people want from the man they didn’t get from his work, because presumably that’s where he’s tried to distill this “life and personality and views” you speak of. What’s any artist but the dregs of his work: I gave that line to Wyatt thirty-odd years ago and as far as I’m concerned it’s still valid.

—but hey look I know what I just did—took my cue from the artist in explaining the artist’s art. So. Oh, hey, here’s a great little segment from a letter Gaddis to his mama (from Mexico City) in April, 1947:

Could you then do this?: Send, as soon as it is conveniently possible, to me at Wells-Fargo:

My high-heeled black boots.

My spurs.

a pair of “levis”—those blue denim pants, if you can find a whole pair

the good machete, with bone handle and wide blade—and scabbard—if

this doesn’t distend package too much.

Bible, and paper-bound Great Pyramid book from H—Street.

those two rather worn gabardine shirts, maroon and green.

Incidentally I hope you got my watch pawn ticket, so that won’t be lost.

PS My mustache is so white and successful I am starting a beard.

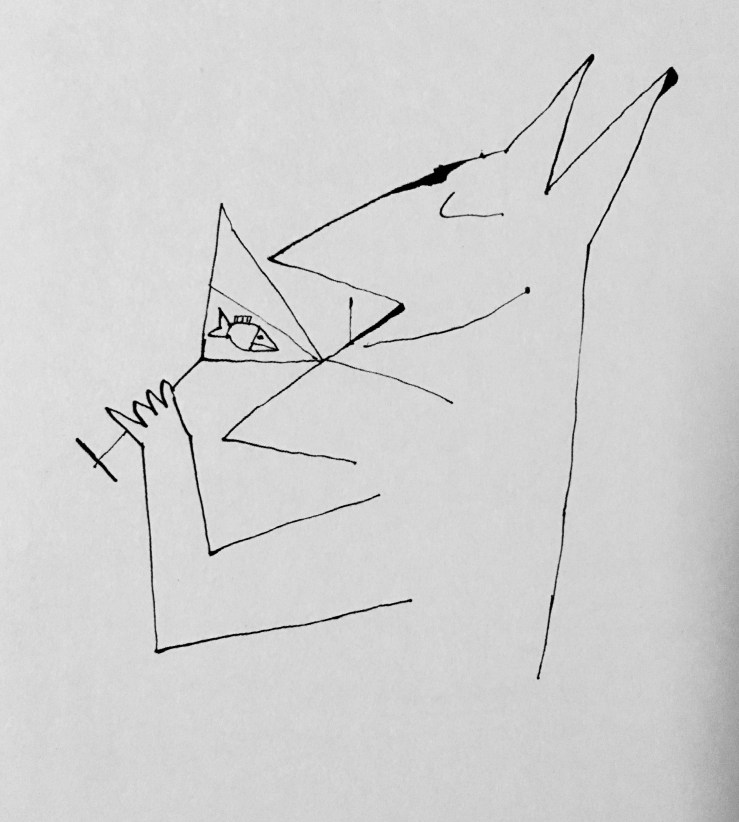

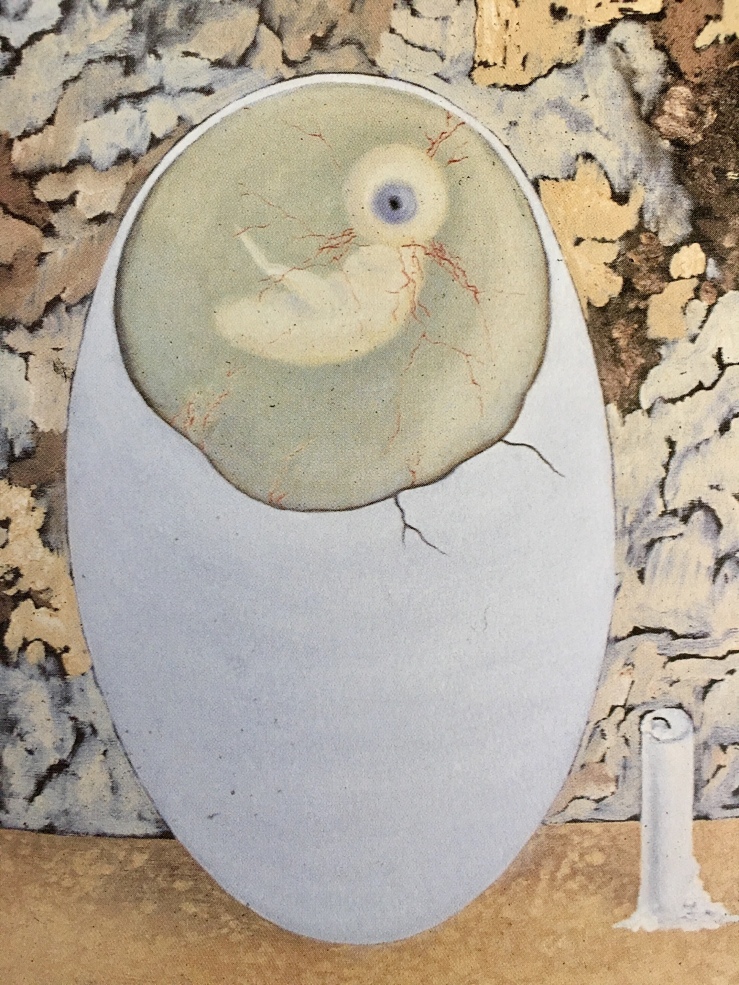

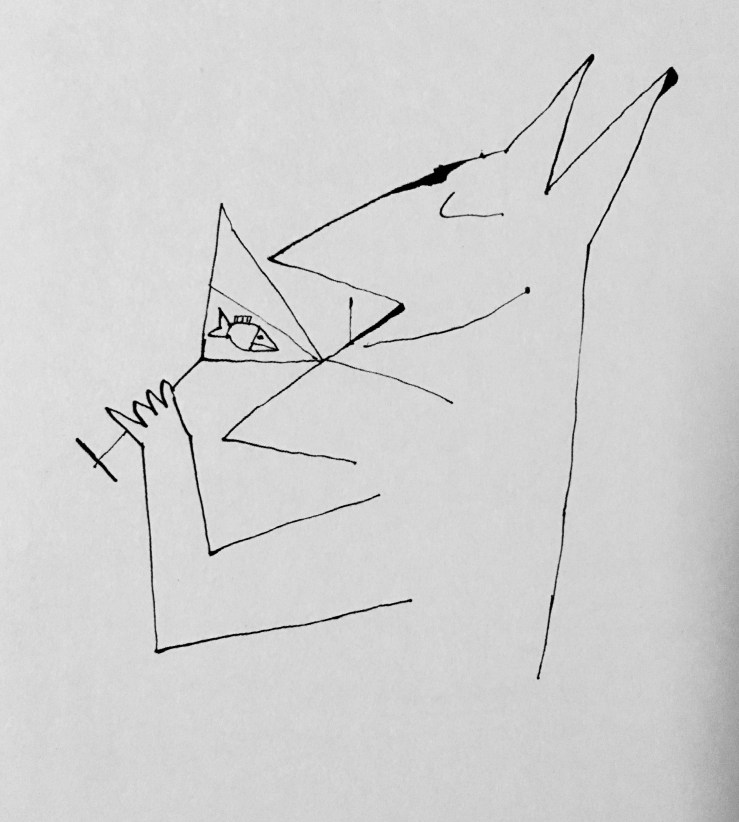

The same day I got The Labyrinth, a collection of mid-century cartooning by Saul Steinberg (new from NYRB, I read a passage in The Gaddis Tapes where Gaddis quotes his friend, Saul Steinberg. That same day my son, eight, went through the whole volume, and asked me what it was, how I was supposed to write about it, etc. Still not sure, but it’s great, heroic, etc. and I hope to post a review at The Comics Journal later this month. Here is Steinberg’s Quixote:

And I like to pretend this is his illustration of some Gaddis character at a party in The Recognitions (even if I recognize it is not):

Bottom of the stack is Paul Kirchner’s latest Hieronymus & Bosch, a sort of MAD Magazine take on eternal damnation that puts the scatology in eschatology. Great stuff.

Not pictured in the stack is Angela Carter’s 1972 novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, which is by my bed and which I keep falling asleep to. It deserves better from me; or maybe it’s a bit of evidence in the emerging truth that I can’t read before bed most of the time most of these days. (Separate blog post, perhaps—chalk it up to a head cold; chalk it up to too many essays to grade; chalk it up to two kids; chalk it up to too much read wine; chalk chalk chalk).

Hope to do better than this in the next 29 days.

1 Knight, Christopher J., William Gaddis, and Tom Smith. “The New York State Writers Institute Tapes: William Gaddis.” Contemporary Literature 42, no. 4 (2001): 667-93. doi:10.2307/1209049.