“Prayer of Columbus” by Walt Whitman

A batter’d, wreck’d old man,

Thrown on this savage shore, far, far from home,

Pent by the sea and dark rebellious brows, twelve dreary months,

Sore, stiff with many toils, sicken’d and nigh to death,

I take my way along the island’s edge,

Venting a heavy heart.

I am too full of woe!

Haply I may not live another day;

I cannot rest O God, I cannot eat or drink or sleep,

Till I put forth myself, my prayer, once more to Thee,

Breathe, bathe myself once more in Thee, commune with Thee,

Report myself once more to Thee.

Thou knowest my years entire, my life,

My long and crowded life of active work, not adoration merely;

Thou knowest the prayers and vigils of my youth,

Thou knowest my manhood’s solemn and visionary meditations,

Thou knowest how before I commenced I devoted all to come to Thee,

Thou knowest I have in age ratified all those vows and strictly kept them,

Thou knowest I have not once lost nor faith nor ecstasy in Thee,

In shackles, prison’d, in disgrace, repining not,

Accepting all from Thee, as duly come from Thee.

All my emprises have been fill’d with Thee,

My speculations, plans, begun and carried on in thoughts of Thee,

Sailing the deep or journeying the land for Thee;

Intentions, purports, aspirations mine, leaving results to Thee.

O I am sure they really came from Thee,

The urge, the ardor, the unconquerable will,

The potent, felt, interior command, stronger than words,

A message from the Heavens whispering to me even in sleep,

These sped me on.

By me and these the work so far accomplish’d,

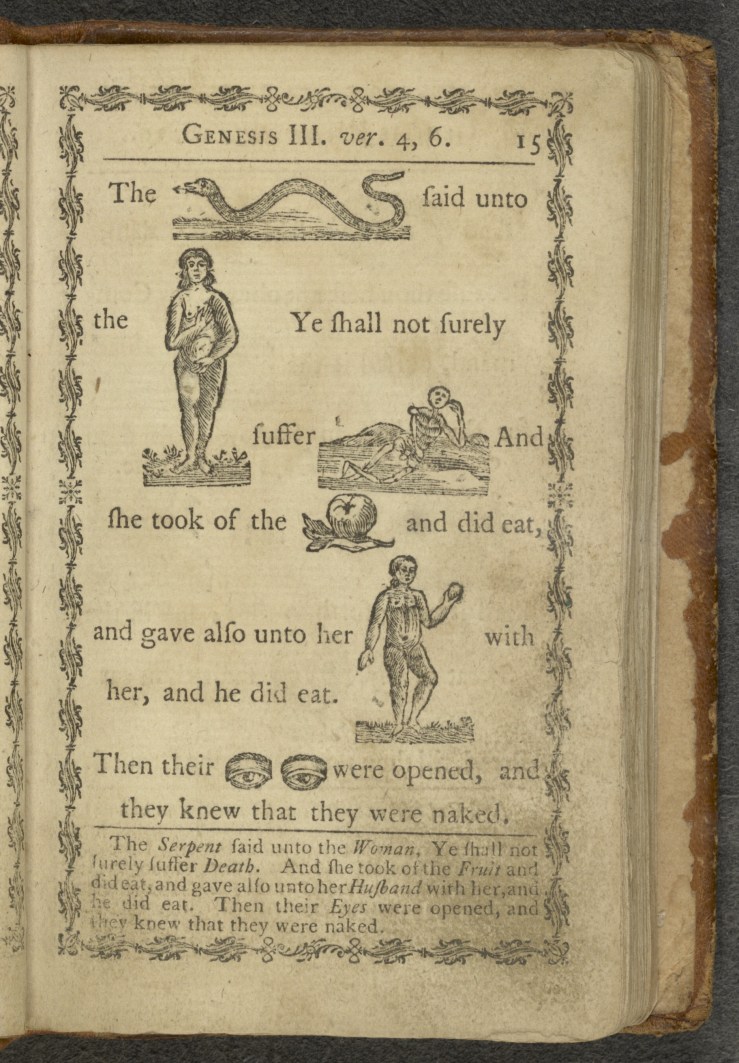

By me earth’s elder cloy’d and stifled lands uncloy’d, unloos’d,

By me the hemispheres rounded and tied, the unknown to the known.

The end I know not, it is all in Thee,

Or small or great I know not–haply what broad fields, what lands,

Haply the brutish measureless human undergrowth I know,

Transplanted there may rise to stature, knowledge worthy Thee,

Haply the swords I know may there indeed be turn’d to reaping-tools,

Haply the lifeless cross I know, Europe’s dead cross, may bud and

blossom there.

One effort more, my altar this bleak sand;

That Thou O God my life hast lighted,

With ray of light, steady, ineffable, vouchsafed of Thee,

Light rare untellable, lighting the very light,

Beyond all signs, descriptions, languages;

For that O God, be it my latest word, here on my knees,

Old, poor, and paralyzed, I thank Thee.

My terminus near,

The clouds already closing in upon me,

The voyage balk’d, the course disputed, lost,

I yield my ships to Thee.

My hands, my limbs grow nerveless,

My brain feels rack’d, bewilder’d,

Let the old timbers part, I will not part,

I will cling fast to Thee, O God, though the waves buffet me,

Thee, Thee at least I know.

Is it the prophet’s thought I speak, or am I raving?

What do I know of life? what of myself?

I know not even my own work past or present,

Dim ever-shifting guesses of it spread before me,

Of newer better worlds, their mighty parturition,

Mocking, perplexing me.

And these things I see suddenly, what mean they?

As if some miracle, some hand divine unseal’d my eyes,

Shadowy vast shapes smile through the air and sky,

And on the distant waves sail countless ships,

And anthems in new tongues I hear saluting me.