The Gospels are powerful not simply because Christ performed miracles and taught kindness, strength, and humility. Humanity has long attributed to certain individuals impossible deeds, tremendous suffering, and inordinate wisdom. We survey the collective memory and search for meaning in the lives of renowned teachers so that they might serve as an example during our own unpredictable, harrowing journey. What separates the story of Jesus from the stories of other merely great people in history is the idea that God manifested itself to humans as a human: wracked with doubt, vulnerable to temptation, victim of unimaginable pain. Although he taught that love is the first commandment, Christ was flailed, tortured, left to die on a cross between two thieves, all ostensibly for no benefit but our own. Wasn’t it Borges who said that every story is either the Odyssey or the Crucifixion? The stories we tell each other, in their reflection, become the same nothing cycle of words, told again and again, a record of our inadequacy and cowardice.

Graham Greene, in his short and powerful novel The Power and the Glory, considers the life and death of Jesus as he narrates the life of a man brought low by pride and circumstances. The last priest someplace in southwestern Mexico flees from the authorities. His hunters seek to free the peasant farmers who populate the land from exploitation and superstition with their own imperfect liberation theologies: the abolition of superstition and private property; the self-sufficiency that follows honest labor. The men in red shirts ride horses and believe in the impending, always near, revolution. On the back of a mule, the father sneaks from town to town, trying to fulfill his duty, but without understanding the significance of the words that tumble clumsily from his mouth in Latin. He performs sacred rites in exchange for sanctuary until even a hiding spot is denied to him. The police have started to execute men and boys in villages who they believe have colluded to shelter this wayward man of God.

As the priest travels, he finds himself stripped not only of the vestments of his profession: his chalice, his incense, his robes, and his bible, but his own air of invincibility, privilege and comfort. Exposed, fearful, living in a state of mortal sin and unable to confess, this fallen man of God, like Christ himself, is destroyed. The priest is, by his own admission, a bad one. He drinks heavily and thinks too much of his own comfort. Led to his profession not so much by attention to the divine will but by a desire for status and privilege, during his exile he recalls fondly dinners lavish dinners with wealthy members of his assembly and the gifts they gave him. While he may have seen that the most of his flock made a meager living on small farms after taxes and fees paid to local bosses, he never stopped to consider the meaning of his own observations, busying himself instead with ambitions for his own greater glory. He is, for the first half of the book, greedy, proud, and self-concerned.

But, as he eludes the authorities and traverses the country, he becomes, in Greene’s capable hands, a symbol of redemption and an affirmation of a full but unrealized life. Words that lacked meaning help to ameliorate the strongest pain he has ever felt. He is jailed, extorted, and rejected by the people who love him the most, but in humiliation finds real faith. Performing the sacred rites of his profession, he confronts the banality of evil and comes to finally realize the true power of the promise he brought to those who came to him:

He had an immense self-importance; he was unable to picture a world in which he was only a typical part — a world of treachery, violence, and lust in which his shame was altogether insignificant. How often the priest had heard the same confession — Man was so limited he hadn’t even the ingenuity to invent a new vice: the animals knew as much. It was for this world that Christ had did; the more evil you saw and heard about you, the greater glory lay around the death. It was too easy to die for what was good or beautiful, for home or children or a civilization — it needed a God to die for the half-hearted and the corrupt.

This is a book about religion and faith, but The Power and the Glory doesn’t require its reader to have an inclination towards either. It is an adventure story, recounted in bold, confident sentences, about a normal man who fears that incorrect choices will cause him to suffer. This fear is real and it manifests itself in the priest’s moral and ethical dilemmas. We are asked to ponder those things that lead from sadness to strength. The priest is us: we see ourselves completely in him and give him our sympathy.

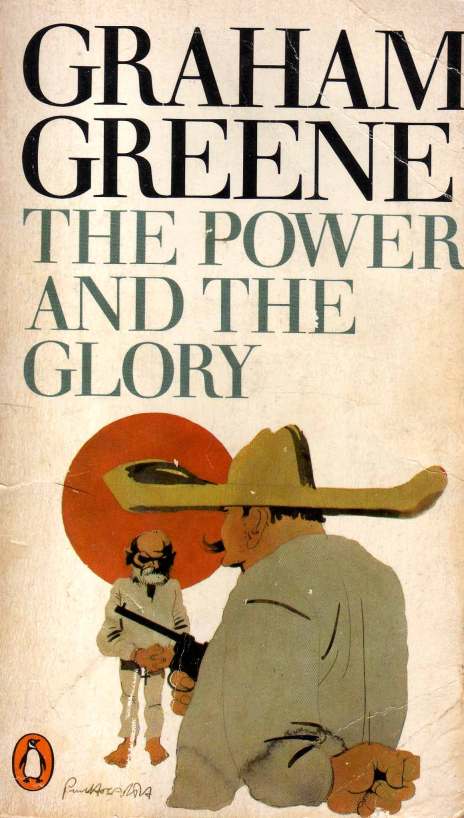

Wonderful review. I’m about to go on a Greene jag, and I think I might prioritise this one. I have the edition with the cover you’ve posted – it’s a great one.

LikeLike

Magnificent post!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on girlwiththepen1118.

LikeLike

Just having read “The Power and the glory” I was interested to see what others have thought of the book. I read your essay with interest and agree that the novel packs a punch. However I disagree that the priest is a symbol of redemption or that he finds real faith. The priest is wracked with guilt over his failures and he admits to being unrepentant. He is consumed with self to the point of self-aggrandizement in stating that God should be protected from the likes of himself. One gets the sense that he visits the dying as the last vestige of a priestly obligation or as Greene states, the priest has a “habit of piety” which is quite different from having real faith. This is a complete departure from Christ, who lived a life of humility, compassion and obedience to the will of the Father. At the heart of the gospel message is that Christ was not destroyed as you state, but rather rose victorious over death just as he said he would.

LikeLike