The Guardian and other sources report that Howard Jacobson has won the 2010 Man Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question. The novel, which we haven’t read, is apparently a comic piece about love, loss, Jewish identity, and male friendship. The win is perhaps something as an upset, as many folks had Tom McCarthy’s C pegged as the favorite (last week bookmaker Ladbrokes even suspended betting on the Booker after bets on C crowded out the competition). Read our review of C here.

The Guardian and other sources report that Howard Jacobson has won the 2010 Man Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question. The novel, which we haven’t read, is apparently a comic piece about love, loss, Jewish identity, and male friendship. The win is perhaps something as an upset, as many folks had Tom McCarthy’s C pegged as the favorite (last week bookmaker Ladbrokes even suspended betting on the Booker after bets on C crowded out the competition). Read our review of C here.

Tag: Literature

“By the Mouth for the Ear” — William Gass on Good Writing

More from The Paris Review’s vaults. In an interview from 1977, William Gass weighs in on the oral/aural aspects of literature–

I think contemporary fiction is divided between those who are still writing performatively and those who are not. Writing for voice, in which you imagine a performance in the auditory sense going on, is traditional and old-fashioned and dying. The new mode is not performative and not auditory. It’s destined for the printed page, and you are really supposed to read it the way they teach you to read in speed-reading. You are supposed to crisscross the page with your eye, getting references and gists; you are supposed to see it flowing on the page, and not sound it in the head. If you do sound it, it is so bad you can hardly proceed. It can’t all have been written by Dreiser, but it sounds like it. Gravity’s Rainbow was written for print, J.R. was written by the mouth for the ear. By the mouth for the ear: that’s the way I’d like to write. I can still admire the other—the way I admire surgeons, bronc busters, and tight ends. As writing, it is that foreign to me.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Death Mask

William Burroughs Shoots William Shakespeare

“David Was A Big Sweater” — The NYT Profiles Karen Green, David Foster Wallace’s Widow

The New York Times profiles Karen Green, David Foster Wallace’s widow. The article details Green’s new art show Sure Is Quiet at the Space Arts Center and Gallery in South Pasadena,California. The article is worth reading in full, of course (it’s actually quite moving), but here are some of Green’s own words from the piece, on Wallace and her art—

David was a big sweater, and I just remember the sweat marks on his pillow when I changed the cases.

. . .

I wanted to redirect my anger, which is useless and fuels nothing, by invading my own privacy and then covering it up.

. . .

There’s been so much chaotic conversation in my head . . . I’ve been thinking, thinking so much. I wanted to take all the chaotic stuff and make it quiet.

. . .

David could be the great artist in the household, I didn’t care . . . I’ve been accused by academic friends of not having the right dialogue with the art world — not being knowledgeable about what’s cool, what’s desirable out there right now. But I’d rather work at Starbucks and make what I want.

. . .

I kept making art because I didn’t know what else to do, and that’s what I’ve always done . . . I felt everyone else was so much more advanced in the grieving process.

. . .

I really was thinking about language, the power of it . . . The power of David’s work, for example, which meant so much to people. But when you get as sick as he was, everything loses meaning.

. . .

You can be charmed and fooled by language . . It doesn’t stop, but it’s never enough.

Angels — Denis Johnson

Angels, Denis Johnson’s 1983 début novel, begins as a small book about not very much and ends as a small book about pretty much everything. Johnson has a keen eye and keener ear for the kinds of marginal characters many of us would rather overlook all together, people who live and sweat and suffer in the most wretched, unglamorous, and anti-heroic vistas of a decayed America. The great achievement of the novel (beyond Johnson’s artful sentences) is in staging redemption for a few–not all, but a few–of its hopeless anti-heroes.

Take Jamie, for instance. Angels opens on this unfortunate young woman as she’s hauling her two young children onto a Greyhound bus. She’s leaving her cheating husband for relatively unknown prospects, lugging her children around like literal and symbolic baggage. Jamie should be sympathetic, but somehow she’s not. She’s someone we’d probably rather not look at, yelling at her kids while she drags on a Kool. Even she knows it. Of two nuns on the bus: “But Jamie could sense that they found her make-up too thick, her pants too tight. They knew she was leaving her husband, and figured she’d turn for a living to whoring. She wanted to tell them what was what, but you can’t talk to a Catholic.” Jamie finds a closer companion, or at least someone equally bored and equally prone to drinking and substance abuse, in Bill Houston. The ex-con, ex-navy man is soon sharing discreet boilermakers with her on the back of the bus, and she makes the first of many bad decisions in deciding to shack up with him over the next few weeks in a series of grim motels.

The bus, the bus stations, the motels, the bars–Johnson details ugly, urgent gritty second-tier cities and crumbling metropolises at the end of the seventies. The effect is simply horrifying. This is a world that you don’t want to be in. Johnson’s evocation never veers into the grotesque, however; he never risks tipping into humor, hyperbole, or distance. The poetic realism of his Pittsburgh or his Chicago is virulent and awful, and as Jamie drunkenly and druggily lurches toward an early trauma, one finds oneself hoping that even if she has to fall, dear God, just let those kids be okay. It’s tempting to accuse Johnson of using the kids to manipulate his audience’s sympathy, but that’s not really the case. Sure, there’ s a manipulation, but it veers toward horror, not sympathy. (And anyway, all good writing manipulates its audience). Johnson’s milieu here is utterly infanticidal and Jamie is part and parcel of the environment: “Jamie could feel the muscles in her leg jerk, she wanted so badly to kick Miranda’s rear end and send her scooting under the wheels, of, for instance, a truck.”

Jamie is of course hardly cognizant of the fact that her treatment of her children is the psychological equivalent of kicking them under a truck. She’s a bad mother, but all of the people in this novel are bad; only some are worse–much worse–than others. Foolishly looking for Bill Houston on the streets of Chicago, she notices that “None of these people they were among now looked at all legitimate.” Jamie is soon conned, drugged, and gang-raped by a brother and his brother-in-law; the sister/wife part of that equation serves as babysitter during the horrific scene.

And oh, that scene. I put the book down. I put the book away. For two weeks. The scene is a red nightmare, the tipping point of Jamie’s sanity, and the founding trauma that the rest of the novel must answer to–a trauma that Bill Houston, specifically, must somehow pay for, redress, or otherwise atone. The rape and its immediate aftermath are hard to stomach, yet for Johnson it’s no mere prop or tasteless gimmick. Rather, the novel’s narrative thrust works to somehow answer to the rape’s existential cruelty, its base meanness, its utter inhumanity. Not that getting there is easy.

Angels shifts direction after the rape, retreating to sun-blazed Arizona, Bill Houston’s boyhood home and home to his mother and two brothers. There’s a shambling reunion, the book’s closest moment of levity, but it’s punctuated and punctured by Jamie’s creeping insanity, alcoholism, and drug addiction. Johnson’s signature humor is desert-dry and rarely shows up to relieve the narrative tension. Jamie hazily evaporates into the background of the book as the Houston brothers, along with a dude named Dwight Snow, plan a bank robbery. Another name for Angels might be Poor People Making Bad Decisions out of Sheer Desperation. Burris, the youngest Houston, has a heroin habit to feed. James Houston is just bored and nihilistic and seems unable to enjoy his wife and child and home. On hearing about the bank robbery plan, Jamie achieves a rare moment of insight: “Rather unexpectedly it occurred to her that her husband Curt, about whom she scarcely ever thought, had been a nice person. These people were not. She knew that she was in a lot of trouble: that whatever she did would be wrong.” And of course, Jamie’s right.

The bank robbery goes wrong–how could it not?–but to write more would risk spoiling much of the tension and pain at the end of Angels. Those who’ve read Jesus’ Son or Tree of Smoke will see the same concern here for redemption, the same struggle, the same suffering. While Jesusian narratives abound in our culture, Johnson is the rare writer who can make his characters’ sacrifices count. These are people. These are humans. And their ugly little misbegotten world is hardly the sort of thing you want to stumble into, let alone engage in, let alone be affected by, let alone be moved by. But Johnson’s characters earn these myriad affections, just as they earn their redemptions. Angels is clearly not for everyone, but fans of Raymond Carver and Russell Banks should make a spot for it on their reading lists (as well as Johnson fans like myself who haven’t gotten there yet). Highly recommended.

Three by Lydia Davis

The massive new volume The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis doesn’t come out until later this month, but you can read the first three stories in the book now at Picador’s website. Read “Story,” “The Fears of Mrs. Orlando,” and “Liminal: The Little Man,” all originally published in Break It Down.

The massive new volume The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis doesn’t come out until later this month, but you can read the first three stories in the book now at Picador’s website. Read “Story,” “The Fears of Mrs. Orlando,” and “Liminal: The Little Man,” all originally published in Break It Down.

“The book educates you about the book” — NPR Profiles Philip Roth

In case you missed it: NPR’s All Things Considered spoke with Philip Roth about his new book Nemesis earlier this week. From the profile–

Nemesis is Roth’s 31st work, and at age 77, he still continues to take risks with his narrative style. In Nemesis, he doesn’t reveal the identity of the narrator until well into the novel.

“It just dawned on me as I was writing along,” Roth explains. “The book educates you about the book.”

Though Roth developed the novel’s narrative structure unexpectedly, he was motivated to do so by a novel that continues to inspire him: Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. In the novel’s first scene, the reader is introduced to Charles Bovary, Madame Bovary’s husband-to-be, as a schoolboy. The scene is narrated by the collective voice of his mocking classmates — a voice that then disappears.

“Well, I don’t have the guts for that,” Roth says, laughing. “That’s what made Flaubert Flaubert, you know. But indeed, it is from the charm of that opening of Madame Bovary that I took my lead.”

See the Official Trailer for the New William Burroughs Documentary, A Man Within

Watch the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature Announcement

Mario Vargas Llosa Wins the 2010 Nobel Prize for Literature

The BBC and other sources report that Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa has won the 2010 Nobel Prize for Literature. He is the first South American to win the Nobel in lit since Gabriel García Márquez won in 1982.

According to the Nobel website, the prize was awarded to Mario Vargas Llosa “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.”

“Things Like Kidnapping the Sex Slave” — William T. Vollmann Speaks of Women

More from The Paris Review’s vaults. Highlights from William T. Vollmann’s 2000 interview (the entire thing is precious. Just precious) —

VOLLMANN: One of the things that I had to do occasionally while I was collecting information for that prostitute story, “Ladies and Red Lights” from The Rainbow Stories, was sit in a corner and pull down my pants and masturbate. I would pretend to do this while I was asking the prostitutes questions. Because otherwise, they were utterly afraid of me and utterly miserable, thinking I was a cop.

. . .

I kept thinking when I first began writing that my female characters were very weak and unconvincing. What is the best way to really improve that? I thought, Well, the best way is to have relationships with a lot of different women. What’s the best way to do that? It’s to pick up whores.

. . .

Also, I often feel lonely.

. . .

I almost never sleep with American prostitutes any more, unless they really want me to—if they are going to get hurt if I don’t.

. . .

Anyway, so when I was in Thailand, I went to a town in the south and bought a young girl for the night. This awful brothel—one of these places hidden behind a flowershop with all these tunnels and locked doors and stuff—was like a prison. I tried to help a couple of the girls but you just can’t get them out. I tried and I couldn’t. I made the mistake of going to the police, trying to have the police get them out—all that did was nearly get them arrested and put in jail, because the police are paid off. I managed to get the raid called off by taking all the cops out to dinner and buying them Johnnie Walker. I bought this fourteen-year-old girl and got her in a truck and drove like hell to Bangkok. I was with this other girl at the time—Yhone-Yhone, a street prostitute, a very happy one. She was my interpreter. She put the fourteen-year-old girl at ease and got her to trust me. We got her set up at a school run by a relative of the king of Thailand. I went up north, met her father, gave him some money, and got a receipt for his daughter. He didn’t know she’d been sold to a brothel. When I met him and told him he said, Oh. I didn’t know that, but, well, whatever she wants. He’s not a bad guy, just a total loser. He’s a former Chiang Kai-shek soldier. They’re all squatters there in Thailand. They can’t read or write. He lives on dried dogs and dried snakes.

INTERVIEWER: You own his daughter?

VOLLMANN: That’s right. I own her. She doesn’t particularly like me, but she was really happy to be out of that place. She loves the school. It’s sort of a vocational school. It’s called something like the Center for the Promotion of the Status of Women. Many former prostitutes are in there.

. . .

The common motif is just prostitution and love.

. . .

I want to take some responsibility and act as well as write. I don’t mean to be an actor, but rather to accomplish things . . . do things that will help people somehow . . . things like kidnapping the sex slave. It would be great if I could make my contribution to abolishing the automobile or eliminating television or something like that.

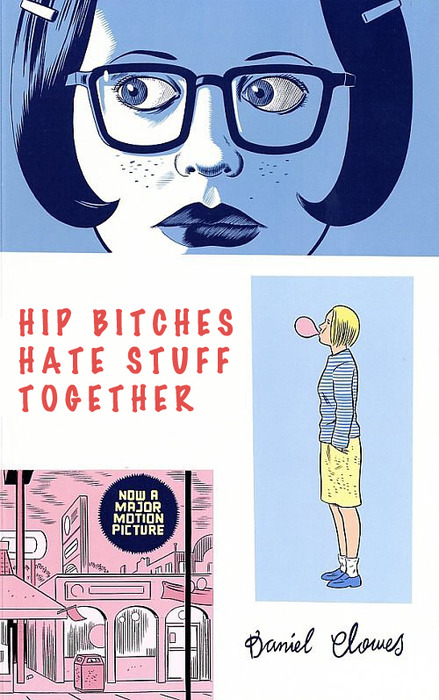

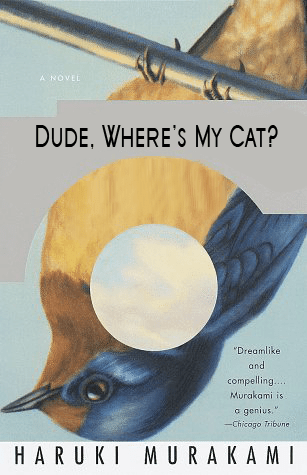

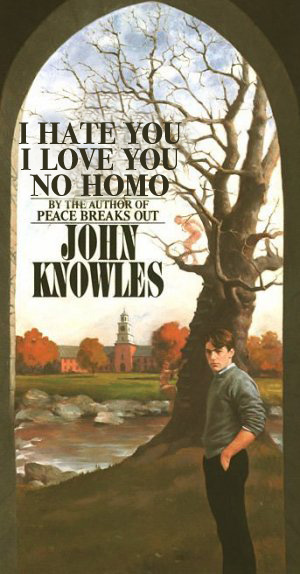

Better Book Titles

Check out the frank and funny images at Better Book Titles (via @MelvilleHouse). A few of our favorites–

James Franco and Michael Cunningham on YA Fiction (and What You Should Never Ask a Writer)

Download The Chamber Four Fiction Anthology

Download The Chamber Four Fiction Anthology. From their website–

Download The Chamber Four Fiction Anthology. From their website–

This anthology contains 25 of the best short stories published on the web in 2009 and 2010 as chosen by the editors of ChamberFour.com, a website dedicated to making reading more enjoyable and more rewarding.In this collection, you’ll find traditional, Carver-esque stories alongside magical realist tales of teleportation, long pieces that slowly pull you in, and single-page punches to the solar plexus. Some of these authors you’ve heard of, others you’ll be discovering for the first time, and you can be sure you’ll see them all again.

There is no factor that unifies the pieces collected here beyond their availability online and that hard-to-define but unmistakable hallmark of quality. These stories are as diverse and as wide in scope as the Internet, but each is true to their shared subject: the attempt to reconcile our world to the struggles of the human soul.

This anthology is DRM-free and free to download. Anybody charging for it is ripping you off.

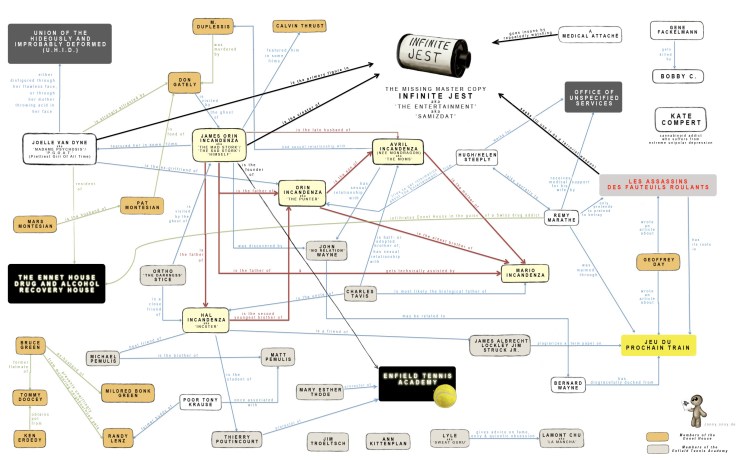

A Plot Diagram of Infinite Jest

Odds and Ends

Hamlet: The Facebook feed edition.

Every book mentioned on Mad Men so far.

Betting odds for the 2010 Nobel Prize for Literature (our boy Cormac McCarthy is at 8 to 1; Bob Dylan is at 150 to 1).

Folks are gettin’ hot and bothered about MFA programs.

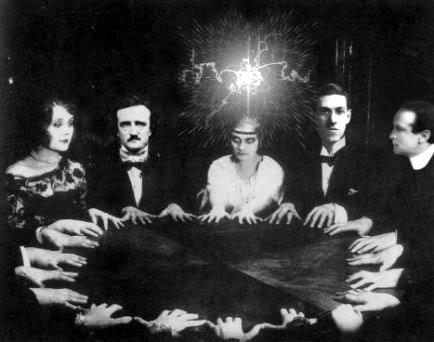

Linking to this post that is tangentially about Jean-Christophe Valtat’s awesome new book Aurorarama gives us an excuse to publish this weird pic of Edgar Allan Poe at a séance–

An inventory of opening sentences.

Vintage Portuguese book covers at A Journey Round My Skull.