1. I was an undergrad in college when I first tried to read Marcel Proust. It was one of those things I did on my own, which is another way of saying that none of his writing was ever assigned to me; neither do I recall any of his writings even appearing in any of the anthologies I was assigned in high school; neither do I recall any of his writings appearing in any of the anthologies I’ve used as a teacher.

2. My initial interest in Proust, late in high school, when the name alone seemed so damn romantic, was aroused, like most people I’ll bet, by the fact that this guy basically wrote one long book, a book that seemed to have at least three names, not counting the names of the individual books and book-length chapters in those individual books.

3. But, like I said, I didn’t try to read Proust until college when I checked out the first volume from the university library. I think it might have actually been a compendium of two or more books that make up the Recherche. Anyway, I can’t recall much, except that I slugged it out through that interminable first chapter, “Combray,” getting absolutely nothing out of it.

4. Since then I’ve read a lot about Proust and his writing, enough to perhaps understand that my first foray into Swann’s Way was probably not from the best angle. I was into decidedly different stuff then—lots of the American postmodernists, English and Irish modernists, etc.—and Proust’s modernism was totally lost on me.

5. Re: Point 4: Perhaps a better way to put it would be to borrow Harold Bloom’s notion that strong/strange writers so assimilate their readers that the readers can no longer see the strangeness/strength. I was assimilated.

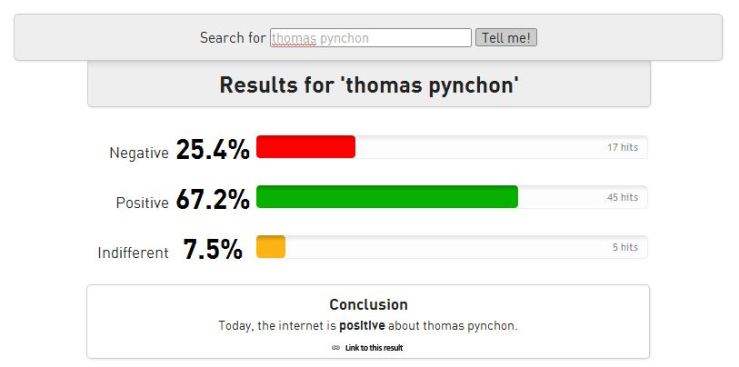

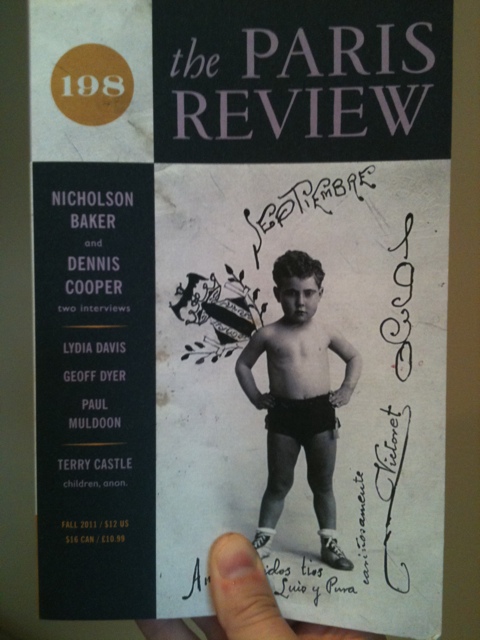

6. Wandering through the used book store I frequent, I spotted Lydia Davis’s translation of Swann’s Way and snapped it up, not because of any real interest in trying Proust again but because of a fannish devotion to Davis, or the idea that Davis would make Proust accessible.

7. (A brief fantasy I had as my hand hovered over the book, before my hand touched the book:

I imagined that Davis had turned Swann’s Way into a series of her own vignettes, that she had parsed and ventriloquized Proust, that her translation would be akin to “Ten Stories from Flaubert.”

This is not the case).

8. (While I’m being parenthetical: This riff started as a “books acquired” post, a post where I take a lousy photograph to document a new book that somehow arrives at Biblioklept World Headquaters. But I read so much of Swann’s Way that the original idea riffed out into this thing. Actually, go ahead and skip Point 8, if you haven’t already. Sorry).

9. The day after buying Davis’s translation I read “Combray” over two short airline trips.

10. Or should it be Combray?—it seems like a self-contained novel.

11. The opening paragraphs of “Combray” are an amazing and strange meditation on sleeping, or rather going to sleep, filled with wonderful little digressions. They are a simultaneously alienating and inviting way to open a book.

Proust writes—

Sometimes, as Eve was born from one of Adam’s ribs, a woman was born during my sleep from a cramped position of my thigh. Formed from the pleasure I was on the point of enjoying, she, I imagined, was the one offering it to me. My body, which felt in hers my own warmth, would try to find itself inside her, I would wake up.

Such a lovely set of images.

I marked it and moved on without trying to figure out exactly what it might mean.

12. Other moments are more lucid, penetrating, insightful:

Even the very simple act that we call “seeing a person we know” is in part an intellectual one. We fill the physical appearance of the individual we see with all the notions we have about him, and of the total picture that we form for ourselves, these notions certainly occupy the greater part.

“Combray” is full of these wonderful, subtle moments, and it includes some of the finest passages on reading and the transformative powers and pleasures of reading that I’ve encountered.

13. The phrase “unknown pleasures” pops out early in the book—is this where Joy Division got the album name?

14. Proust seems to hit on the idea of unknown pleasures again and again, speculative pleasures, idealized pleasures.

15. Introduced to the writer Bergotte by Swann and Bloch, the young narrator muses:

One of these passages by Bergotte, the third or fourth that I had isolated from the rest, filled me with a joy that could not be compared to the joy I had discovered in the first one, a joy I felt I was experiencing in a deeper, vaster, more unified region of myself, from which all obstacles and partitions had been removed.

The passage concludes with the narrator deciding that he has accessed the “‘ideal passage’ by Bergotte,” an idealization through which he finds his mind “enlarged.”

16. Cataloging the meditations on unknown pleasures in the book would take forever though, and I’m just riffing here.

17. (Although I do love and will thus bring up a late passage where the narrator longs to walk in the woods with “a peasant girl,” one like a “local plant” (!), through which he will access new and individual and unknown pleasures, “Obscurely awaited, immanent and hidden. . . “).

18. Stray note: Swann is described as having a “Bressant-style” haircut, which the end notes describe as “a crew cut in front and longer in the back.” Is this not known colloquially as a mullet? Am I to understand that Swann sports a Kentucky waterfall?

19. Proust’s greatest strength in “Combray” seems to be his ability to move from the physical to the metaphysical, from object to memory. And then back again.

20. An empty statement: The writing is beautiful.

21. Still, there’s something irksome about the narrator (Marcel?): I stopped writing “mama’s boy” in the margin after the third such notation.

22. Re: Point 21: Is this why I never stuck it out with Proust? Is this why, despite acknowledging “The writing is beautiful,” I am not particularly inclined to see what happens next? (And next and next and next . . .)

23. Re: Point 22: I think here of Cormac McCarthy’s assertion in a 1992 New York Times interview that Proust is “not literature” because it doesn’t “deal with issues of life and death.” McCarthy’s quote may or may not be out of context (not here; here it’s in perfectly sound context. I’m talking about proper context in the interview, which is to say that he may or may not have been riffing off the cuff).

24. Okay, from the McCarthy interview:

His list of those whom he calls the “good writers” — Melville, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner — precludes anyone who doesn’t “deal with issues of life and death.” Proust and Henry James don’t make the cut. “I don’t understand them,” he says. “To me, that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange.”

25. Maybe I bring it up because I’ve read so much of McCarthy and the heroes on his list above and find them so compelling, find the protagonists and antagonists so compelling, and while Proust’s narrator is hardly repellent, I find myself occasionally wanting to give him a wedgie.

26. (Never having had the desire to give Ishmael a wedgie, or the underground man a wedgie, or Lucas Beauchamp a wedgie, or Cornelius Suttree a wedgie).

27. Okay. The sentiment I’ve just expressed seems cruel.

28. The same sensitivity I find occasionally overbearing in the narrator is exactly what makes so many of the passages and insights in the text so extraordinary.

29. The narrator is some kind of specialized receptive organic instrument, a psyche keenly attuned to the physical world who mediates that world through emotion, memory, psychological projection—language.

30. The narrator is some kind of membrane but also a self, his articulations winding from reader to self through memory to the natural world, to its phenomena, and back through desire, thought, anticipation, idealization, all back through memory again, back to the reader again. And if tracing these articulations is exhausting, the process also undeniably yields unknown pleasures.