Lars Iyer’s first novel Spurious (Melville House) is by turns, witty, sad, and profound, and garnered serious acclaim on its release earlier this year. Spurious originated in a blog of the same name. There are two sequels on the way—Dogma should be on shelves in early 2012, and Exodus the year after. Lars teaches philosophy at Newcastle University (so it’s no wonder that Spurious reads like a discursive philosophy course by way of the Marx brothers). Lars was kind enough to talk to Biblioklept in depth about his work and writing. In addition to his teaching, writing, and blogging, you will also find Lars on Twitter.

Lars Iyer’s first novel Spurious (Melville House) is by turns, witty, sad, and profound, and garnered serious acclaim on its release earlier this year. Spurious originated in a blog of the same name. There are two sequels on the way—Dogma should be on shelves in early 2012, and Exodus the year after. Lars teaches philosophy at Newcastle University (so it’s no wonder that Spurious reads like a discursive philosophy course by way of the Marx brothers). Lars was kind enough to talk to Biblioklept in depth about his work and writing. In addition to his teaching, writing, and blogging, you will also find Lars on Twitter.

Biblioklept: Your novel Spurious began as a blog and then was published by Melville House, a thriving indie publisher that also began life as a blog. At a recent talk you gave at the HowTheLightGetsIn philosophy and music festival, you discuss the freedom blogging allows for writers to develop their “legitimate strangeness.” Why is “legitimate strangeness” important for writers, and how does blogging help facilitate it?

Lars Iyer: Sometimes it is necessary to depart. Sometimes it is necessary to leave it all behind. That’s how I understood the act of blogging, back when I started Spurious, the blog which shares the same name as the novel.

As someone who had made some progress as an academic – a journey which implies valuable training as well as compromise and despair – I thought a kind of exodus was necessary, from existing forms of published writing. Leave it all behind!, I told myself. Leave the Egypt of introductory books and academic journals and edited collections behind. Leave the slave-drivers behind, and the sense you have of being a slave. Leave capitalism and capitalist relations behind. Leave behind any sense of the importance of career and advancement. Leave behind those relationships that are modelled on investment and return.

Sometimes a kind of solitude is necessary. You need to be alone, to regather your forces, to marshall your strength. But what is really necessary is a solitude in community. You’re on your own, depending on your own resources. But your solitude is lightened: because you know that there are others like you, who have likewise expelled themselves from captivity; because you know that others share your sense of disgust and self-disgust, that they too have gone out to the desert to do battle with the demons sent by capitalism into each of our souls; because there are others, like you, who see writing as both scourge and liberation, others who see it as a spiritual trial, others looking to destroy who they were and be reborn, and to keep themselves in rebirth.

In the end, the desert is paradise, and the world the blogger has left behind, with its whips and fleshpots, is the real desert.

Cultivate your legitimate strangeness: that was my mantra. ‘Cultivate’, because it is a struggle, a kind of asceticism. To drive the demons out, you have to know that they are there. A kind of self-knowledge is necessary – not the petty narcissism we find in the ‘misery memoir’, but a growing awareness of those forces that have constituted you, that have made you what you are. ‘Your legitimate strangeness’: ‘Your’, because it is yours, your space, the person you are, that you have become, even as you might alter this space, remake it. ‘Legitimate’ – that part of you that is not yet subsumed by capitalism, that free part of yourself that is not a slave. ‘Strangeness’ – because it must appear strange to the slaves and their masters, to everyone around you.

Why is this important to the writer? Some of us write because of our alienation. We have had no one to speak to, no friends, no conversations. There was no one around. Thoreau went to the woods to find himself. We went to our rooms. We went to literature, and philosophy, without knowing anything of literature and philosophy. We worked on our own.

There is something pathetic about this. Shouldn’t we have been fighting the world instead? Shouldn’t we have been ready on the barricades? But there were no barricades. There was no solidarity. We belonged to nothing, and had gone a little mad, a little reclusive, from belonging to nothing.

In one sense, since we lacked education, lacked culture, since our world was not one which valued the ideas and writers that we came to, our exodus was pathetic. We were imitators, play-pretending at being what we are not. We’d come too late; the party was over. We stood in the ruins, and the ruins mocked us. What could we have achieved, that had not been achieved to a much higher level before? What could we have made, that had not already been made, and much more competently, much more measuredly? We lacked the basic skills. We lacked the ability to write – even that. We lacked the breadth of culture, the breadth of scholarship.

But seen in another light, we discovered ourselves as outsiders, like those outsider artists who practiced their vocation outside of institutions. What we made was crude and simple, true — especially when compared to what went before – but it did have a certain power to affect. It had an urgency, a desperation, which might, perhaps, appeal to others. We were capable of only scraps and fragments, to be sure – dreck – but dreck marked by a moving sincerity.

I wondered – and this was the beginning of Spurious, the novel, and of its sequels – whether there was a way of folding this sense of posthumousness, of coming too late and lacking the old skills, into the practice of writing. Maybe it was time to come back from the desert, which had taught me only the extent and depth of my stupidity. Maybe it was time to write with a new kind of writing . . .

Biblioklept: That “sense of posthumousness, of coming too late” figures heavily in Spurious. Is Spurious the “new kind of writing” you are aiming for? While the book has a fragmentary, even elliptical quality, it also reminds me of novels in the picaresque tradition. What form does this new kind of writing you invoke take?

LI: Spurious is a book on its hands and knees. For me, it feels like the last book, the last burst of laughter before the world ends. But it also feels like the first one, because it has loosened the hold of the past. It says: a whole form of literary pretence is over.

Writing to a friend, in 1916, before the composition and publication of the work that would make him famous, the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig wrote, ‘My true book will appear only as an opus posthumum: I do not want to have to defend it or know about its “influence”’. He writes something similar, a year later, in another letter: ‘I will only truly speak after my death …, I place my entire life beneath the sign of that “posthumousness”’. Rosenzweig was confident that there would be a culture to evaluate his work. He was confident that there would be a place for his posthumous work among the greats – that there would still be greats, such that he might find his place among them. He was sure, in other words, that the old world would continue as it was; that there would still be master-works, still be the geniuses who wrote them, and still be the critics whose evaluations would be trusted by a general public.

A similar confidence in an author today would be a sign of delusion. Literature is one strand among many in our multi-braided culture. True, it retains something of its prestige; it is studied at universities, reviewed in serious newspapers — but it occupies an increasingly marginal role. The ‘great names’ are, for the most part, only cultural markers, ready for commercialisation (Kafka oven gloves in the tourist shop in Prague; the Brontë Balti House in Haworth; the Pride and Prejudice fully immersive interactive environment). But it is not only marginalisation that should be feared; recognition, too, should be. I think of the stupidity of documentary ‘infotainment’ on writers and artists, and rise of the vast, say-everything biography, that says nothing at all (as Mark Fisher has written, the biography is an end of history form, making the reassuring claim that ‘it was all about people’).

Literature continues. But it does so, in contemporary literary fiction, as a kind of empty form. As the anonymous blogger of Life Unfurnished has put it: contemporary literary fiction gives ‘the appearance alone of literature’; it is a genre ‘in which, for the writer, the sense of Writing Literature is dominant, and, for the reader, the sense of Reading Literature is dominant’.

Reviewing Jean-Luc Godard’s film Every Man For Himself, Pauline Kael writes, ‘I got the feeling that Godard doesn’t believe in anything anymore; he just wants to make movies, but maybe he doesn’t really believe in movies anymore, either’. Without agreeing with Kael’s assessment of Godard, I’d like to paraphrase her formulation: I think literary writers want to write literary fiction without believing in literature – without, indeed, believing in anything at all.

It seems to me that the literary gestures are worn out – the creation of character, plot, the contrivance of high-literary language and style as much as the avoidance of high-literary language and style, and the abandonment of most elements of the creation of character and plot. The ‘short, elliptical sentences’ of which the blogger of Life Unfurnished writes, the ‘absence of fulsome description’, the ‘signs of iconoclastic casualness’, the ‘colloquialisms’, the ‘lack of trajectory’, the ‘air of the incidental’: all are likewise exhausted.

What, then, is to be done? As writers, as readers, we are posthumous. We’ve come too late. We no longer believe in literature. Once you accept this non-belief, once you affirm it in a particular way, then something may be possible.

Witold Gombrowicz seems to advocating a return to older forms of literary insouciance: ‘Where are the good old days, when Rabelais wrote as a child might pee against a tree, to relieve himself? The old days when literature took a deep breath and created itself freely, among people, for people!’ But we cannot simply return to Rabelais, as Gombrowicz knew. Too much has happened! If a kind of self-consciousness is a distinguishing mark of the contemporary literary novelist, this is not something that can be relinquished altogether. The role of centuries of writing – of the rise of the nineteenth century bourgeois novel, of modernism and so on – must be marked.

But it can be marked by portraying our distance now from the conditions in which the great works of literature and philosophy were written. W. and Lars, the characters in Spurious, revere Rosenzweig. But this is also reverence for a culture that would deem Rosenzweig and his work important – a culture that is completely different from the one which W. and Lars occupy. True, they revere contemporary masters, too – the filmmaker Béla Tarr, for example – but Tarr lives far away, in very different conditions. W. and Lars occupy the world of the present, and the world that valued the ideas they value, the world that sustained those ideas and nurtured their production, has disappeared. Much of the humour of the book comes from the fact that its characters are men out of time – gasping in awe at Rosenzweig’s work at one moment, leafing through gossip magazines at another; proclaiming a great love of Kafka one minute, playing Doom on a mobile phone the next.

It is in this sense that there might appear to be an overlap between Spurious and novels in the picaresque tradition, which extends from sixteenth century Spain to the present day. Picaresque, it has been argued, appears as a result of a tension between an old world and a new one. The Spain of the first picaresque novels was in a period of difficult transition, from the stability of the medieval order to the age of a new, self-assertive individuality. Poverty and war were all around. The picaresque is produced in a world where human solidarity is lacking, and the individual no longer has a place in the world. The episodic journeys of the picaresque novel reflect the lack of coherence of its central characters, the lack of secure identity – a kind of cosmic loneliness.

Some picaresque features can be found in Spurious. The novel is episodic, and its characters lack a place in the world, even a place in history. W. and Lars play-pretend at various roles, trying on the mantle of the religious person or the philosophical thinker. W., in particular, yearns after friendship. But the characters are not roguish, as the picaro of a picaresque novel is supposed to be. W. is perfectly sincere. And picaros do not usually come in pairs.

Biblioklept: Speaking of your pair Lars and W., there’s a strong friendship there that strikes me as very realistic and actually quite moving. Reading Spurious I was reminded strongly of one of my own friendships, which is perhaps based on equal parts degradation and love. Lars and W. evoke both extreme pathos and a kind of deep existential anxiety that manifests in humor. Parts of Spurious read almost like verbal slapstick (if that metaphor can hold any water). How important is humor—what do you think the humor in Spurious is “doing”?

LI: Humour? I’m with Gilbert Sorrentino: ‘In a country such as ours we have reached a point at which there is hardly anything left to do but laugh or cry. It’s a kind of hysterical laughter, it’s strained and unreasoning laughter, or it is a morbid, bleak sobbing. I don’t think that anything is going to get changed in this country except that it’s going to become grimmer’.

Sorrentino’s referring to the USA, but he could just as well be referring to the UK. We lack the grounds for belief, for hope, for a future. There’s economic disaster — not simply the credit crunch, but neoliberalism in general: corporatisation, unemployment, job insecurity, casualisation, the privatisation of public utilities. Beyond this, there are the effects of climate change: drought and hunger, failure of whole nations, wars, migrants. The temptation of ‘morbid, bleak sobbing’ is extreme, as is the desire to drink oneself into oblivion like the barflies in Béla Tarr films.

Sometimes, it feels that there is an imposture in the very fact of being alive. It is as though getting out of bed in these terrible conditions were already an imposture, let alone trying to think or write. What can we do, really do, about the disaster? ‘To hope is to contradict the future’, Cioran says somewhere. Better to lie down and wait for the end. Better to give up before you begin.

‘I think joy is a lack of understanding of the situation in which we find ourselves’, Andrei Tarkovsky says, with marvellous ill-temper. And, on another occasion: ‘I accept happiness only in children and the elderly, with all others I am intolerant’. It’s true that joy and happiness seem ill-suited to our times, all the more in that joy and happiness are promoted in that ideology of positivity which is everywhere today. But perhaps there is a sense in which one might legitimately laugh at the apocalypse, albeit with what Sorrentino calls a ‘hysterical laughter’.

A sage in the Ramayana tells us that there are three things which are real: god, human folly, and laughter. ‘Since the first two surpass human comprehension’, he says, ‘we must do what we can with the third’. So we must laugh at folly, laugh at greed and smugness, opportunism and corruption, as eternal flaws in the human condition; laugh, and dream of a better world, knowing that it won’t come.

But this kind of laughter is too genial for me. It treats human folly as eternal, which I’m sure in many ways it is, but ignores suffering, dying, the real hell of our globalised world. And I worry that it also spares the one who laughs. True, you can laugh retrospectively at your own stupidities. What an idiot I was when I young!, you might say. But there is a broader sense in which we are, each of us, implicated in the present state of the world. It is our responsibility, in some important way. For me, to laugh sagely at one’s own foolishness is still too little.

What is the humour of Spurious doing, then? As many reviews of the novel have shown, the ‘verbal slapstick’ of the characters is part of a whole tradition of double acts and comic routines. I wanted W.’s insults of Lars to exhibit the same virtuosity as the physical humour of the Marx Brothers or Buster Keaton. I think there is a whole art of the insult. But I think something else is going in the novel, too.

Alenka Zupančič argues that comedies are never truly intersubjective. ‘[C]omedy is above all a dialogical genre’, she grants; but comic heroes are ‘extracted, by their passion, from the world of the normal intersubjective communication’. What they are really doing is seeking ‘to converse solely with their ‘it/id”’. Dialogues, in comedy, are really monologues; the hero is really only obsessed with his basic, chaos-ridden drives. As Zupančič suggests, ‘The comedy of such dialogues does not come from witty and clever exchanges between two subjects, or from local misunderstandings that make (comic) sense on another level of dialogue, but from the fact that the character is not really present in the dialogue he is engaged in’. On this account, the cruelty of the ‘verbal slapstick’ of the friendship in Spurious, which sees W. continually berating his poor friend, would actually be directed at W. himself. W., the only candidate for being the ‘comic hero’ of Spurious, would use Lars as merely the occasion for the continuation of his monologue.

But this interpretation doesn’t quite work for me, either. The ‘it’ that drives the exchanges of the characters is not only a feature of W.’s psychic makeup, of the chaos of his drives. Both characters are mesmerised by a real disaster. And both — particularly W. — are mesmerised by their partial responsibility for this disaster. The ‘strained and unreasoning’ laughter of Spurious is a response to the grimness of the world that is of our making.

Biblioklept: For me, that “strained and unreasoning” laughter is a big part of why I enjoyed the book—I identified with the characters. Spurious isn’t really, to borrow a phrase from David Shields, a “novelly-novel,” but it does have elements of a “novelly-novel” (including characters with whom some readers will strongly identify). At the same time, its short sections, fragmentary nature, and willingness to cite entire paragraphs of other texts point to a new kind of writing, one perhaps anchored in its origins as a blog. How did you compose Spurious? How does the novel differ from the blog?

LI: ‘A page is good only when we turn it and find life urging along …’, says one of Calvino’s characters in Our Ancestors. I hope that’s what a reader can find in Spurious: life urging along. I hope readers recognise something of their own friendships in that of W. and Lars. Spurious is not, I think, a ‘novelly-novel’. It’s new in some way – it has characters, some elements of plot, but it doesn’t resemble other books. And I think this is due to its origins. Blogging, and then combining different categories of posts, allowed me to discover, through editing, a new kind of novel.

Blogging demands immediacy. Telling the story of W. and Lars, I couldn’t rely on readers having followed it from the start. Every day, with my blog posts, I had to present these characters and their situation anew, and in a manner vivid enough to engage any potential reader. In doing so, I felt rather like the writer of a strip cartoon. Charles Schultz’s Peanuts had longer narrative arcs, but each sequence he published in daily newspapers had to stand on its own. Likewise with the posts at the blog. Each post had to have its own internal drama, a kind of ‘verbal slapstick’, even as it could be contained within a larger narrative arc.

My loyalty was, for a long time, to the readers of my blog, and I produced new material for them daily. But I thought some of the thematic strands developing at the blog – the trips to Freiburg and Dundee, for example, or the reflections on Kafka and on the Messiah – were being obscured by the quantity and disparateness of W. and Lars material. A selection had to be made. This is where the work of editing began, of the practice of literary montage that would lead to Spurious.

Tarkovsky, in his book about film, narrates the long process of assembling the various fragments that comprise the finished film, Mirror. ‘I am seeking a principle of montage which would permit me to show the subjective logic — the thought, the dream, the memory — instead of the logic of the subject’, he said. He was looking for a way to combine various elements – short narrative sequences, pieces of music and poetry, etc. – into a living whole.

I was doing the same thing, in my own way. Spurious is a hybrid of many elements of the blog. There was a story about W. and Lars, but also one about damp –– a real story, which I wrote about at the blog. I added quotations, too, as well as incorporating the narratives of the lives of various thinkers. And I edited until I felt that life was urging along.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

LI: I have thousands of pages of photocopies, which I made, full of ardour, during my first jobs as an academic. I thought I’d never get a permanent job, and wanted to make my own library of knock-off books in my rented room. Perse, Trakl, Tsvetayeva, Duras, and so many others: no printed book could mean as much to me as my annotated duplicates.

The memoir-in-food is something of a cliché at this point, but Gabrielle Hamilton’s new book Blood, Bones & Butter came with enough accolades (including a glowing blurb from Anthony Bourdain) and positive early reviews (

The memoir-in-food is something of a cliché at this point, but Gabrielle Hamilton’s new book Blood, Bones & Butter came with enough accolades (including a glowing blurb from Anthony Bourdain) and positive early reviews ( Meg Howrey’s new novel Blind Sight tells the story of Luke Prescott, a bright, introspective seventeen year old obsessed with brain biology. Raised by a hippie mother and two half-sisters, Luke gets the opportunity to the summer before college with his estranged father, a famous television star. In Los Angeles, Luke gets to know his father better, sorting out the difference between public persona and private truth; this process in turn leads Luke to re-evaluate his own sense of identity. There’s also some pot-smoking and sex. Howrey moves the narrative between Luke’s first-person voice (in the past tense) to a third person present tense narrator. At times this disjunction seems like a lazy shorthand to allow the reader to see something Luke can’t see (or doesn’t want the reader to see), but it works nicely on the whole, underlining the gaps between truth and belief that the novel seeks to explore. Blind Sight is new in hardback from

Meg Howrey’s new novel Blind Sight tells the story of Luke Prescott, a bright, introspective seventeen year old obsessed with brain biology. Raised by a hippie mother and two half-sisters, Luke gets the opportunity to the summer before college with his estranged father, a famous television star. In Los Angeles, Luke gets to know his father better, sorting out the difference between public persona and private truth; this process in turn leads Luke to re-evaluate his own sense of identity. There’s also some pot-smoking and sex. Howrey moves the narrative between Luke’s first-person voice (in the past tense) to a third person present tense narrator. At times this disjunction seems like a lazy shorthand to allow the reader to see something Luke can’t see (or doesn’t want the reader to see), but it works nicely on the whole, underlining the gaps between truth and belief that the novel seeks to explore. Blind Sight is new in hardback from  In The Woman Who Shot Mussolini, Frances Stonor Saunders plays historical detective, reconstructing the story of Violet Gibson, who fired on Mussolini in April of 1926 (she grazed his nose). Gibson, the daughter of the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, was 50 when she shot Mussolini, and perhaps more than a little crazy. She was almost lynched after shooting Il Duce, but the not-so-benevolent dictator pardoned her, and she was quickly returned to England, where she spent the rest of her life in an insane asylum. Saunders’s book explores whether Gibson’s attack was the motivation of an insane woman or part of a bigger conspiracy theory, illustrating her mystery with poignant black and white photos. And although Saunders focuses on the little-known Gibson, she works to draw parallels between the would-be assassin and Mussolini. Saunders’s exploration of an otherwise unremarked upon episode balances historical scholarship with the pacing and rhythm of an historical thriller. New in trade paperback edition from

In The Woman Who Shot Mussolini, Frances Stonor Saunders plays historical detective, reconstructing the story of Violet Gibson, who fired on Mussolini in April of 1926 (she grazed his nose). Gibson, the daughter of the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, was 50 when she shot Mussolini, and perhaps more than a little crazy. She was almost lynched after shooting Il Duce, but the not-so-benevolent dictator pardoned her, and she was quickly returned to England, where she spent the rest of her life in an insane asylum. Saunders’s book explores whether Gibson’s attack was the motivation of an insane woman or part of a bigger conspiracy theory, illustrating her mystery with poignant black and white photos. And although Saunders focuses on the little-known Gibson, she works to draw parallels between the would-be assassin and Mussolini. Saunders’s exploration of an otherwise unremarked upon episode balances historical scholarship with the pacing and rhythm of an historical thriller. New in trade paperback edition from

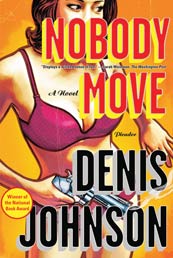

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night.

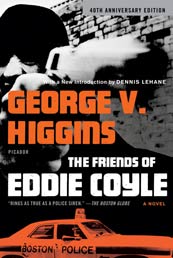

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night. I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire.

I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire. I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that.

I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that. In her debut novel, All the Living, C.E. Morgan tells the story of Aloma, a would-be pianist who forgoes her dreams of artistic freedom to play wifey to her young lover Orren who must take sole responsibility of running the family tobacco farm after his family dies in a car accident. Aloma knows nothing about farming and even less about the grief Orren suffers. She’s an orphan herself, but with no memory of her own parents, she finds it hard to connect to overworked Orren as he slowly slips away. A nearby minister who hires her to play church services paradoxically relieves and exacerbates Almoa’s despair when he enters her life. Morgan’s novel is a slow-burn, often painful, sometimes slow, but also guided by a poetic spirituality that resists easy interpretations. (Oh, and she’ll also make you run for a thesaurus every few pages). All the Living is new in trade paperback from

In her debut novel, All the Living, C.E. Morgan tells the story of Aloma, a would-be pianist who forgoes her dreams of artistic freedom to play wifey to her young lover Orren who must take sole responsibility of running the family tobacco farm after his family dies in a car accident. Aloma knows nothing about farming and even less about the grief Orren suffers. She’s an orphan herself, but with no memory of her own parents, she finds it hard to connect to overworked Orren as he slowly slips away. A nearby minister who hires her to play church services paradoxically relieves and exacerbates Almoa’s despair when he enters her life. Morgan’s novel is a slow-burn, often painful, sometimes slow, but also guided by a poetic spirituality that resists easy interpretations. (Oh, and she’ll also make you run for a thesaurus every few pages). All the Living is new in trade paperback from  Anne Michaels’s The Winter Vault begins in Egypt, in 1964, where Canadian engineer Avery Escher is part of a team trying to help the Nubians who will be displaced by the Aswan High Dam. He and his wife Jean share a houseboat on the Nile, but what might have been a year of romantic adventure devolves into the tragedy of a culture displaced and a family eroded. The pair separate and return to Canada, where Jean takes up with Lucjan whose stories of Nazi-occupied Warsaw inform the novel’s second half. The Winter Vault is poetically dense and often overly-lyrical, sometimes offering self-important and ponderous dialogues in place of concise plotting. And while Michaels treats the tragedies of the occupied Poles and Nubians with a certain sensitivity, her engagement veers awfully close to what Lee Siegel has termed “

Anne Michaels’s The Winter Vault begins in Egypt, in 1964, where Canadian engineer Avery Escher is part of a team trying to help the Nubians who will be displaced by the Aswan High Dam. He and his wife Jean share a houseboat on the Nile, but what might have been a year of romantic adventure devolves into the tragedy of a culture displaced and a family eroded. The pair separate and return to Canada, where Jean takes up with Lucjan whose stories of Nazi-occupied Warsaw inform the novel’s second half. The Winter Vault is poetically dense and often overly-lyrical, sometimes offering self-important and ponderous dialogues in place of concise plotting. And while Michaels treats the tragedies of the occupied Poles and Nubians with a certain sensitivity, her engagement veers awfully close to what Lee Siegel has termed “ Jenniemae & James is Brooke Newman‘s new memoir about her father’s unlikely relationship with the family maid. James Newman was a brilliant mathematician (he coined the term “googol”); Jenniemae Harrington “was an underestimated, underappreciated, extremely overweight woman who was very religious, dirt poor, and illiterate.” Newman wants us to see a unique–and deep–friendship between the pair that defies 1940s/50s norms in Washington D.C., but it’s hard not to think that there’s at least some whitewashing going on here. Undoubtedly the two shared an affinity and connected through a love of numbers, but it’s hard to see more in this than an employer-employee relationship–and one still colored by the politics of the pre-Civil Rights era. Jenniemae, black mammy, sassy, Southern, larger-than-life, quick with folk wisdom and colorful quips–it all seems like a one-sided vision, a take on the

Jenniemae & James is Brooke Newman‘s new memoir about her father’s unlikely relationship with the family maid. James Newman was a brilliant mathematician (he coined the term “googol”); Jenniemae Harrington “was an underestimated, underappreciated, extremely overweight woman who was very religious, dirt poor, and illiterate.” Newman wants us to see a unique–and deep–friendship between the pair that defies 1940s/50s norms in Washington D.C., but it’s hard not to think that there’s at least some whitewashing going on here. Undoubtedly the two shared an affinity and connected through a love of numbers, but it’s hard to see more in this than an employer-employee relationship–and one still colored by the politics of the pre-Civil Rights era. Jenniemae, black mammy, sassy, Southern, larger-than-life, quick with folk wisdom and colorful quips–it all seems like a one-sided vision, a take on the