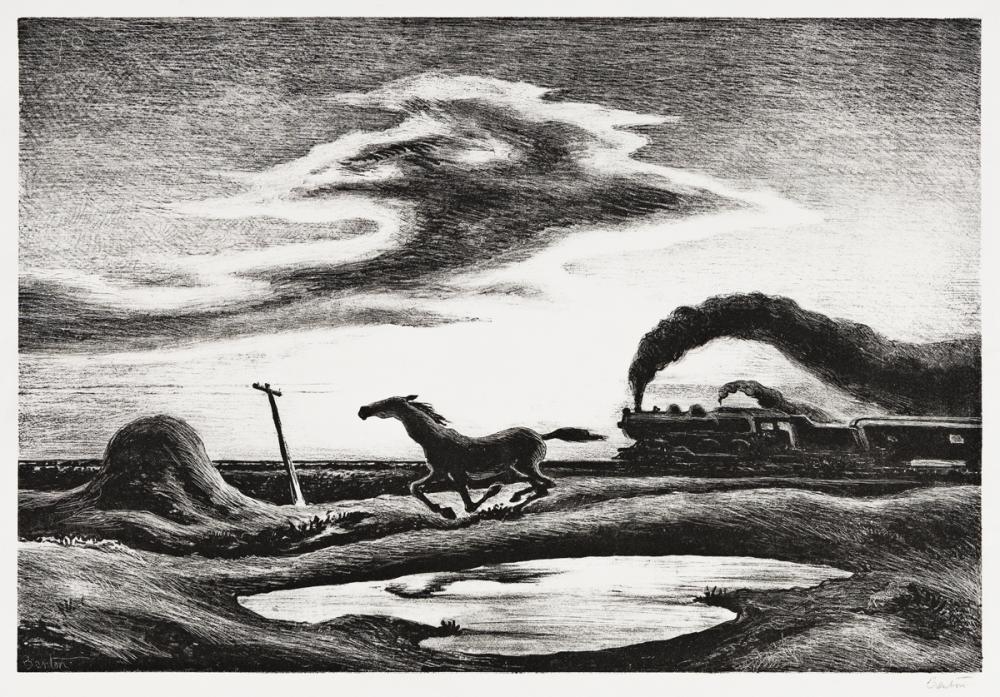

With blunt grace, Denis Johnson navigates the line between realism and the American frontier myth in his perfect novella Train Dreams. In a slim 116 pages, Johnson communicates one man’s life story with a depth and breadth that actually lives up to the book’s blurb’s claim to be an “epic in miniature.” I read it in one sitting on a Sunday afternoon, occasionally laughing aloud at Johnson’s wry humor, several times moved by the pathos of the narrative, and more than once stunned at the subtle, balanced perfection of Johnson’s prose, which inheres from sentence to paragraph to resonate throughout the structure of the book.

The opening lines hooked me:

In the summer of 1917 Robert Grainier took part in an attempt on the life of a Chinese laborer caught, or anyway accused of, stealing from the company stores of the Spokane International Railway in the Idaho Panhandle.

Three of the railroad gang put the thief under restraint and dragged him up the long bank toward the bridge under construction fifty feet above the Moyea River. A rapid singsong streamed from the Chinaman voluminously. He shipped and twisted like a weasel in a sack, lashing backward with his one free fist at the man lugging him by the neck.

The matter-of-fact violence here complicates everything that follows in many ways, because Grainier it turns out is pretty much that rare thing, a good man, a simple man who tries to make a life in the Idaho Panhandle at the beginning of the 20th century. The rest of the book sees him trying—perhaps not consciously—to somehow amend for the strange near-lynching he abetted.

Grainier works as a day laborer, felling the great forests of the American northwest so that a network of trains can connect the country. Johnson resists the urge to overstate the obvious motifs of expansion and modernity here, instead expressing depictions of America’s industrial growth at a more personal, even psychological level:

Grainier’s experience on the Eleven-Mile Cutoff made him hungry to be around other such massive undertakings, where swarms of men did away with portions of the forest and assembled structures as big as anything going, knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms, always bigger, longer, deeper.

Grainier’s hard work keeps him from his wife and infant daughter, and the separation eventually becomes more severe after a natural calamity, but I won’t dwell on that in this review, because I think the less you know about Train Dreams going in the better. Still, it can’t hurt to share a lovely passage that describes Grainier’s courtship with the woman who would become his wife:

The first kiss plummeted him down a hole and popped him out into a world he thought he could get along in—as if he’d been pulling hard the wrong way and was now turned around headed downstream. They spent the whole afternoon among the daisies kissing. He felt glorious and full of more blood than he was supposed to have in him.

The passage highlights Johnson’s power to move from realism into the metaphysical and back, and it’s this precise navigation of naturalism and the ways that naturalism can tip the human spirit into supernatural experiences that makes Train Dreams such a strong little book. In the strange trajectory of his life, Grainier will be visited by a ghost and a wolf-child, will take flight in a biplane and transport a man shot by a dog, will be tempted by a pageant of pulchritude and discover, most unwittingly, that he is a hermit in the woods. In Johnson’s careful crafting, these events are not material for a grotesque picaresque or a litany of bizarre absurdities, but rather a beautiful, resonant poem-story, a miniature history of America.

Train Dreams is an excellent starting place for those unfamiliar with Johnson’s work, and the book will rest at home on a shelf with Steinbeck’s naturalist evocations or Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy. I have no idea why the folks at FS&G waited almost a decade to publish it (Train Dreams was originally published in a 2002 issue of The Paris Review), but I’m glad they did, and I’m glad the book is out now in trade paperback from Picador, where it should gain a wider audience. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note: Biblioklept originally published this review in May of 2012. I still haven’t seen the Clint Bentley-directed film adaptation.]