“Dreams”

by

Guy de Maupassant

They had just dined together, five old friends, a writer, a doctor and three rich bachelors without any profession.

They had talked about everything, and a feeling of lassitude came over them, that feeling which precedes and leads to the departure of guests after festive gatherings. One of those present, who had for the last five minutes been gazing silently at the surging boulevard dotted with gas-lamps, with its rattling vehicles, said suddenly:

“When you’ve nothing to do from morning till night, the days are long.”

“And the nights too,” assented the guest who sat next to him. “I sleep very little; pleasures fatigue me; conversation is monotonous. Never do I come across a new idea, and I feel, before talking to any one, a violent longing to say nothing and to listen to nothing. I don’t know what to do with my evenings.”

The third idler remarked:

“I would pay a great deal for anything that would help me to pass just two pleasant hours every day.”

The writer, who had just thrown his overcoat across his arm, turned round to them, and said:

“The man who could discover a new vice and introduce it among his fellow creatures, even if it were to shorten their lives, would render a greater service to humanity than the man who found the means of securing to them eternal salvation and eternal youth.”

The doctor burst out laughing, and, while he chewed his cigar, he said:

“Yes, but it is not so easy to discover it. Men have however crudely, been seeking for—and working for the object you refer to since the beginning of the world. The men who came first reached perfection at once in this way. We are hardly equal to them.”

One of the three idlers murmured:

“What a pity!”

Then, after a minute’s pause, he added:

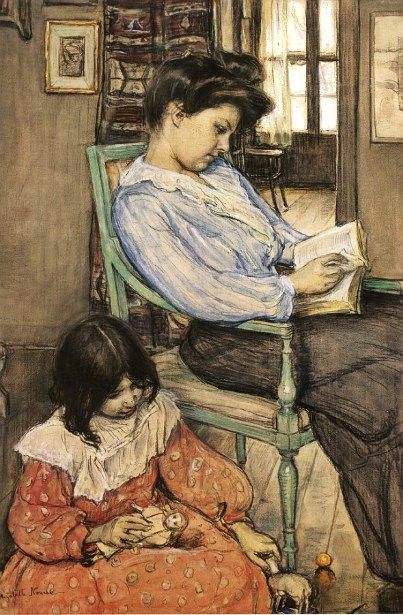

“If we could only sleep, sleep well, without feeling hot or cold, sleep with that perfect unconsciousness we experience on nights when we are thoroughly fatigued, sleep without dreams.”

“Why without dreams?” asked the guest sitting next to him.

The other replied:

“Because dreams are not always pleasant; they are always fantastic, improbable, disconnected; and because when we are asleep we cannot have the sort of dreams we like. We ought to dream waking.”

“And what’s to prevent you?” asked the writer.

The doctor flung away the end of his cigar.

“My dear fellow, in order to dream when you are awake, you need great power and great exercise of will, and when you try to do it, great weariness is the result. Now, real dreaming, that journey of our thoughts through delightful visions, is assuredly the sweetest experience in the world; but it must come naturally, it must not be provoked in a painful, manner, and must be accompanied by absolute bodily comfort. This power of dreaming I can give you, provided you promise that you will not abuse it.”

The writer shrugged his shoulders:

“Ah! yes, I know—hasheesh, opium, green tea—artificial paradises. I have read Baudelaire, and I even tasted the famous drug, which made me very sick.”

But the doctor, without stirring from his seat, said:

“No; ether, nothing but ether; and I would suggest that you literary men should use it sometimes.”

The three rich bachelors drew closer to the doctor.

One of them said:

“Explain to us the effects of it.”

And the doctor replied:

“Let us put aside big words, shall we not? I am not talking of medicine or morality; I am talking of pleasure. You give yourselves up every day to excesses which consume your lives. I want to indicate to you a new sensation, possible only to intelligent men—let us say even very intelligent men—dangerous, like everything else that overexcites our organs, but exquisite. I might add that you would require a certain preparation, that is to say, practice, to feel in all their completeness the singular effects of ether.

“They are different from the effects of hasheesh, of opium, or morphia, and they cease as soon as the absorption of the drug is interrupted, while the other generators of day dreams continue their action for hours.

“I am now going to try to analyze these feelings as clearly as possible. But the thing is not easy, so facile, so delicate, so almost imperceptible, are these sensations.

“It was when I was attacked by violent neuralgia that I made use of this remedy, which since then I have, perhaps, slightly abused.

“I had acute pains in my head and neck, and an intolerable heat of the skin, a feverish restlessness. I took up a large bottle of ether, and, lying down, I began to inhale it slowly.

“At the end of some minutes I thought I heard a vague murmur, which ere long became a sort of humming, and it seemed to me that all the interior of my body had become light, light as air, that it was dissolving into vapor.

“Then came a sort of torpor, a sleepy sensation of comfort, in spite of the pains which still continued, but which had ceased to make themselves felt. It was one of those sensations which we are willing to endure and not any of those frightful wrenches against which our tortured body protests.

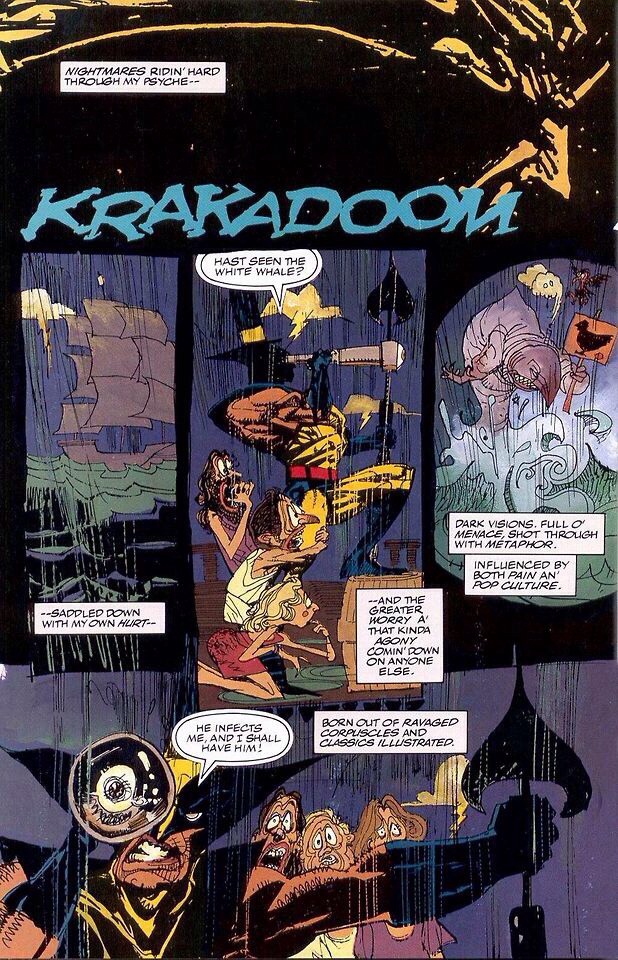

“Soon the strange and delightful sense of emptiness which I felt in my chest extended to my limbs, which, in their turn, became light, as light as if the flesh and the bones had been melted and the skin only were left, the skin necessary to enable me to realize the sweetness of living, of bathing in this sensation of well-being. Then I perceived that I was no longer suffering. The pain had gone, melted away, evaporated. And I heard voices, four voices, two dialogues, without understanding what was said. At one time there were only indistinct sounds, at another time a word reached my ear. But I recognized that this was only the humming I had heard before, but emphasized. I was not asleep; I was not awake; I comprehended, I felt, I reasoned with the utmost clearness and depth, with extraordinary energy and intellectual pleasure, with a singular intoxication arising from this separation of my mental faculties.

“It was not like the dreams caused by hasheesh or the somewhat sickly visions that come from opium; it was an amazing acuteness of reasoning, a new way of seeing, judging and appreciating the things of life, and with the certainty, the absolute consciousness that this was the true way.

“And the old image of the Scriptures suddenly came back to my mind. It seemed to me that I had tasted of the Tree of Knowledge, that all the mysteries were unveiled, so much did I find myself under the sway of a new, strange and irrefutable logic. And arguments, reasonings, proofs rose up in a heap before my brain only to be immediately displaced by some stronger proof, reasoning, argument. My head had, in fact, become a battleground of ideas. I was a superior being, armed with invincible intelligence, and I experienced a huge delight at the manifestation of my power.

“It lasted a long, long time. I still kept inhaling the ether from my flagon. Suddenly I perceived that it was empty.”

The four men exclaimed at the same time:

“Doctor, a prescription at once for a liter of ether!”

But the doctor, putting on his hat, replied:

“As to that, certainly not; go and let some one else poison you!”

And he left them.

Ladies and gentlemen, what is your opinion on the subject?

(Translation by Kenneth Rexroth)

(Translation by Kenneth Rexroth)