My Struggle, Book 1 by Karl Ove Knausgaard. English translation by Don Bartlett. First edition trade paperback by FS&G, 2013. Cover design by Charlotte Strick and Bill Zindel, with cover art by Bill Zindel.

I couldn’t really get past page 80 of My Struggle, but I like Zindel’s zany design for the first volume enough to hold on to it. Kinda reminds me of those Vintage Contemporaries I so adore.

A lot of people didn’t like the design though, and FS&G didn’t end up publishing the rest of Zindel’s designs, which would’ve looked pretty neat as a complete set. As literary critic Scott Esposito put it at the time “the market has spoken, and it hates the original paperback.”

Instead, FS&G went with variations on this—

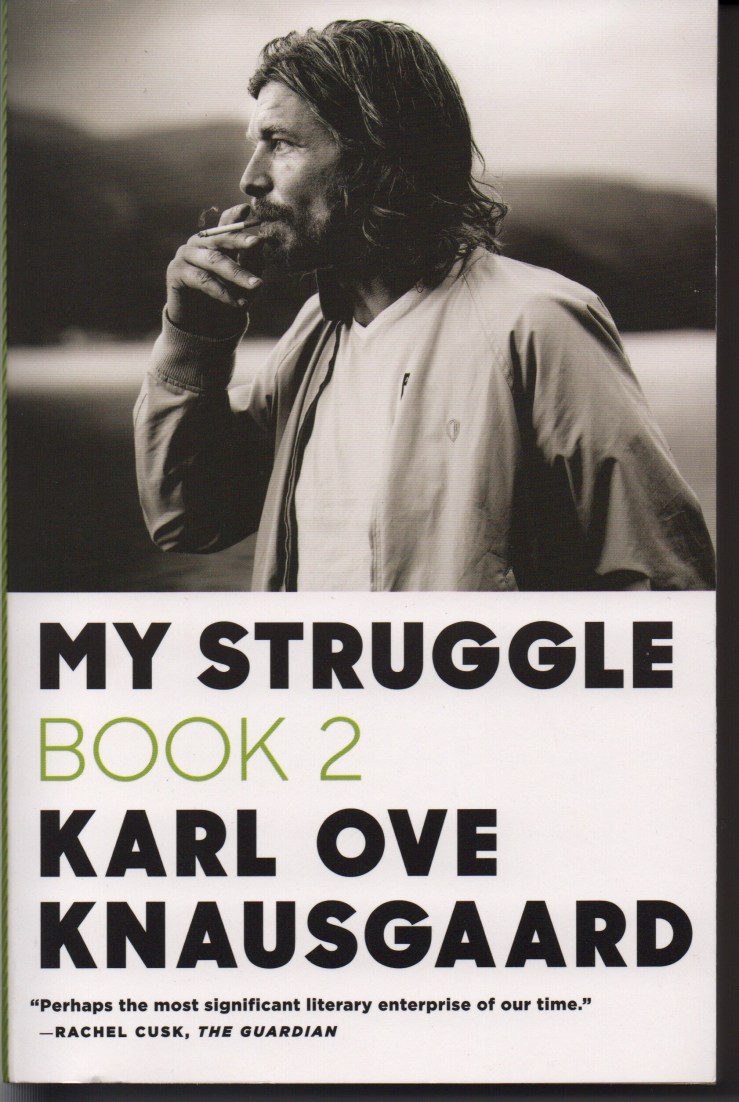

My Struggle, Book 2 by Karl Ove Knausgaard. English translation by Don Bartlett. First edition trade paperback by FS&G, 2014. Cover design by Charlotte Strick; photograph by Andreas Eikseth Nygjerd.

Look at our boy Knausgaard, smokin’ away! This cover is boring but not Bad, which makes it far less interesting than the Bad Knausgaard cover which is actually very Good. The Book 2 cover (and subsequent covers in the series) are safe and “stylish”—and when I write “stylish,” I use it in the way many writers use it—thoughtlessly, blankly—stylish as a word that points vaguely to the idea of style, the zeitgeistiness of style. Etc. (Again—I encourage you to check out Zindel’s vision for the whole series).

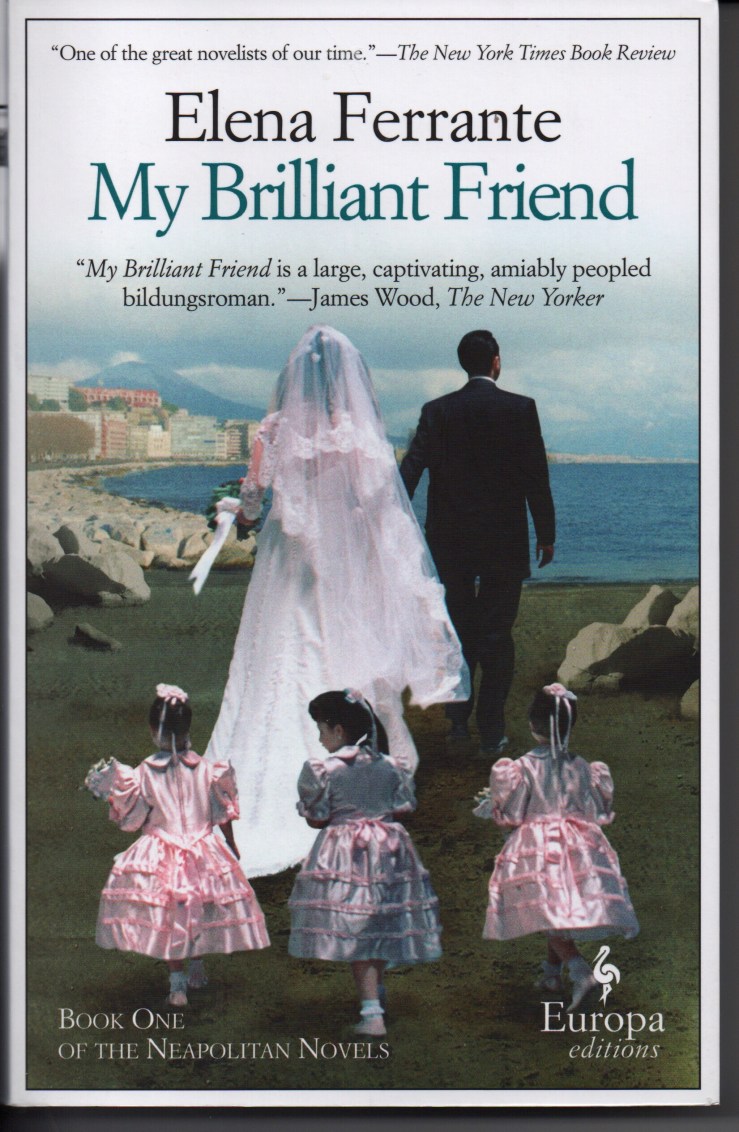

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante. English translation by Ann Goldstein. Fifteenth printing, Europa Editions, 2015. Book design by Emanuele Ragnisco; cover photo by Anthony Boccaccio.

My Brilliant Friend is brilliant, my friend.

Its cover is awful, and the subsequent covers in the so-called Neapolitan Novels quartet are somehow worse.

A good friend who’s never steered me wrong with a reading recommendation told me to read Ferrante last year, but I didn’t—it wasn’t the hype that put me off (although the hype put me off), but the covers. I finally acquiesced to an audiobook version, and after getting a few chapters in, wanted the text. So I caved.

But my god, the cover—why?

The publisher and art director(s) claim that the Ferrante covers are bad on purpose.

An article in Quartz that I found simply by googling “Ferrante covers awful” yields this nugget:

…Sandro Ferri, Europa Editions’ publisher, says the covers were not an accident of too many cooks in the design kitchen, but rather a conscious choice. Writes Ferri in an email to Quartz, “The ‘vulgarity’ is our intention. We don’t want to make the typical ‘literary’ cover designed for an audience of ultra-sophisticated readers. … Ferrante’s novels are a mix of popular literature and highbrow, intellectual writing. We want to communicate this though our covers as well.”

And in a Slate interview, EE co-founder/publisher Sandra Ozzola again asserts that the decision for tacky covers was, um, purposeful:

From the time of our first conversation with Elena Ferrante about her intention to write this novel, we knew the book’s title and that it would be the story of a long friendship between women—and that it would conclude with a scene of a very vulgar Neapolitan wedding. The wedding and Elena’s impression of it … is an extremely important moment in the book. That’s why I intentionally searched for a photo that was “kitsch.” This design choice continued in the subsequent books, because vulgarity is an important aspect of the books, of all that Elena wants to distance herself from.

If we take a book’s cover to be where the book “begins,” where we first start to read the text, then EE’s awful kitschy crappy ugly covers signal postmodern irony—a joke on perception, the marketplace, high-low aesthetics, etc. The covers work as a kind of metatextual critique, then, as Ozzola seems to suggest above—a critique that relies on the reader’s understanding of the novel’s central character’s aesthetic viewpoint.

Well so then: Are the covers indeed ironic critiques of book-cover-aesthetics? Are we to take these covers as pop art parodies of books that traffic in romantic aspirations, that are, like, marketed to women?

Or are these covers simply designed to appeal to the very market that they would claim to ironically mock?

The have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too postmodern answer to these questions is, of course, “Yes.”

To fully appreciate the aesthetic irony of the Ferrante novels of course requires reading the Ferrante novels. And undoubtedly, many people are put off reading these books because of the covers. So much so that Ferrante’s novels got new covers for their Australian release. The new covers were designed by W.H. Chong:

Mr Chong told The New Daily it can be dangerous to try irony on a book’s cover – especially if the joke isn’t clear to readers.

“You have to signal the irony really clearly otherwise the recipient doesn’t realise the irony,” Mr Chong said.

“You have to signal the irony really clearly” — okay, sure. But the finest satire never announces itself as such.

Chong’s new covers feature simple black-and-white photographs, and they have received praise. But in a sense, the Australian covers seem, at least to me, to echo those Knausgaard updates—safe, boring even. But I’d much rather be seen reading one of those, than, say, the original EE edition of The Story of the Lost Child, which has maybe the worst cover I’ve ever seen.

Europa Editions’ forthcoming Ferrante collection, Frantumaglia, has a great cover, by the way.

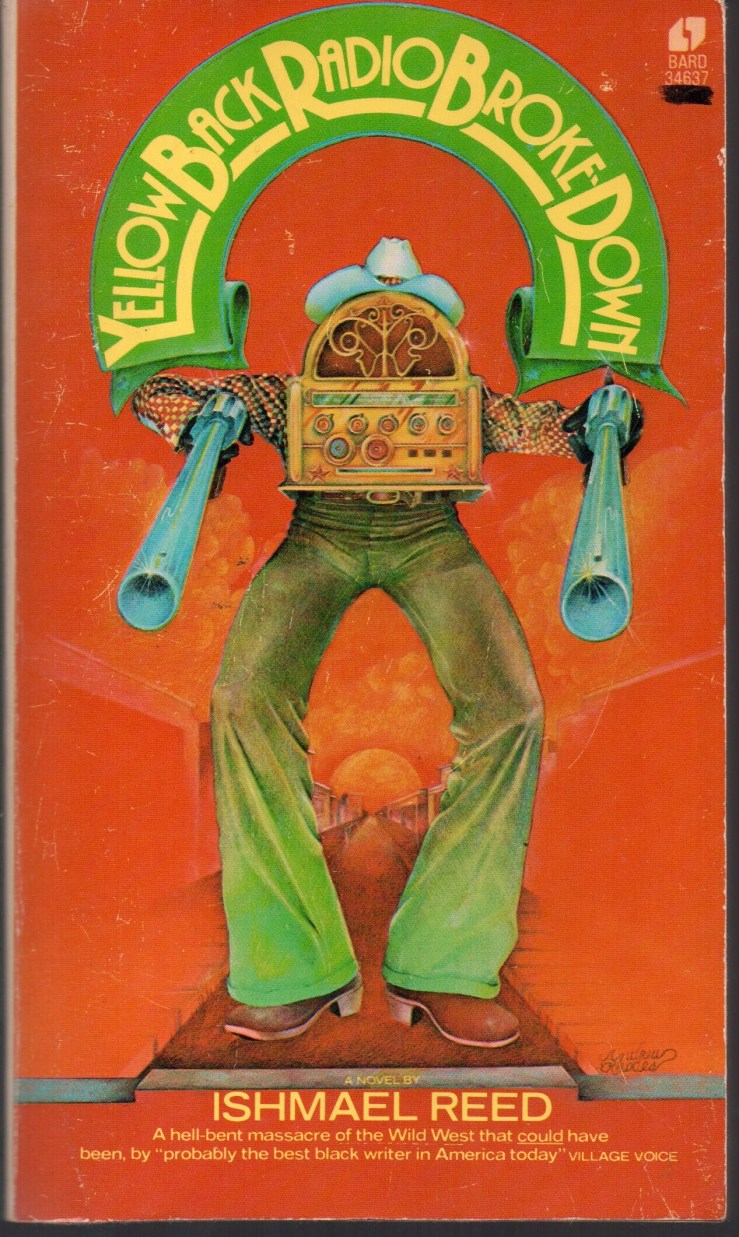

The Free-Lance Pallbearers by Ishmael Reed. 1969 mass market paperback by Bantam Books. No designer or illustrator credited. I finished this last week—a slim, strange, dazzling work.

The Free-Lance Pallbearers by Ishmael Reed. 1969 mass market paperback by Bantam Books. No designer or illustrator credited. I finished this last week—a slim, strange, dazzling work.