Falling from favor, or grace, some high artifice, down he dropped like a discredited predicate through what he called space (sometimes he called it time) and with an earsplitting crack splattered the base earth with his vital attributes. Oh, I’ve had a great fall, he thought as he lay there, numb with terror, trying desperately to pull himself together again. This time (or space) I’ve really done it! He had fallen before of course: short of expectations, into bad habits, out with his friends, upon evil days, foul of the law, in and out of love, down in the dumps—indeed, as though egged on by some malevolent metaphor generated by his own condition, he had always been falling, had he not?—but this was the most terrible fall of all. It was like the very fall of pride, of stars, of Babylon, of cradles and curtains and angels and rain, like the dread fall of silence, of sparrows, like the fall of doom.

Category: Writers

A Coffee Chronology

A COFFEE CHRONOLOGY

Giving dates and events of historical interest in legend, travel, literature, cultivation, plantation treatment, trading, and in the preparation and use of coffee from the earliest time to the present

900[L]—Rhazes, famous Arabian physician, is first writer to mention coffee under the name bunca or bunchum.[M]

1000[L]—Avicenna, Mahommedan physician and philosopher, is the first writer to explain the medicinal properties of the coffee bean, which he also calls bunchum.[M]

1258[L]—Sheik Omar, disciple of Sheik Schadheli, patron saint and legendary founder of Mocha, by chance discovers coffee as a beverage at Ousab in Arabia.[M]

1300[L]—The coffee drink is a decoction made from roasted berries, crushed in a mortar and pestle, the powder being placed in boiling water, and the drink taken down, grounds and all.

1350[L]—Persian, Egyptian, and Turkish ewers made of pottery are first used for serving coffee.

1400–1500—Earthenware or metal coffee-roasting plates with small holes, rounded and shaped like a skimmer, come into use in Turkey and Persia over braziers. Also about this time appears the familiar Turkish cylinder coffee mill, and the original Turkish coffee boiler of metal.

1428–48—Spice grinder to stand on four legs first invented; subsequently used to grind coffee.

1454[L]—Sheik Gemaleddin, mufti of Aden, having discovered the virtues of the berry on a journey to Abyssinia, sanctions the use of coffee in Arabia Felix.

1470–1500—The use of coffee spreads to Mecca and Medina.

1500–1600—Shallow iron dippers with long handles and small foot-rests come into use in Bagdad and in Mesopotamia for roasting coffee.

1505[L]—The Arabs introduce the coffee plant into Ceylon.

1510—The coffee drink is introduced into Cairo.

1511—Kair Bey, governor of Mecca, after consultation with a council of lawyers, physicians, and leading citizens, issues a condemnation of coffee, and prohibits the use of the drink. Prohibition subsequently ordered revoked by the sultan of Cairo.

1517—Sultan Selim I, after conquering Egypt, brings coffee to Constantinople.

1524—The kadi of Mecca closes the public coffee houses because of disorders, but permits coffee drinking at home and in private. His successor allows them to re-open under license.

1530[L]—Coffee drinking introduced into Damascus.

1532[L]—Coffee drinking introduced into Aleppo.

1534—A religious fanatic denounces coffee in Cairo and leads a mob against the coffee houses, many of which are wrecked. The city is divided into two parties, for and against coffee; but the chief judge, after consultation with the doctors, causes coffee to be served to the meeting, drinks some himself, and thus settles the controversy.

Critical Mass (Gravity’s Rainbow)

“I think that there is a terrible possibility now, in the World. We may not brush it away, we must look at it. It is possible that They will not die. That it is now within the state of Their art to go on forever—though we, of course, will keep dying as we always have. Death has been the source of Their power. It was easy enough for us to see that. If we are here once, only once, then clearly we are here to take what we can while we may. If They have taken much more, and taken not only from Earth but also from us—well, why begrudge Them, when they’re just as doomed to die as we are? All in the same boat, all under the same shadow… yes… yes. But is that really true? Or is it the best, and the most carefully propagated, of all Their lies, known and unknown?

“We have to carry on under the possibility that we die only because They want us to: because They need our terror for Their survival. We are their harvests… .

“It must change radically the nature of our faith. To ask that we keep faith in Their mortality, faith that They also cry, and have fear, and feel pain, faith They are only pretending Death is Their servant—faith in Death as the master of us all—is to ask for an order of courage that I know is beyond my own humanity, though I cannot speak for others… . But rather than make that leap of faith, perhaps we will choose instead to turn, to fight: to demand, from those for whom we die, our own immortality. They may not be dying in bed any more, but maybe They can still die from violence. If not, at least we can learn to withhold from Them our fear of Death. For every kind of vampire, there is a kind of cross. And at least the physical things They have taken, from”“Earth and from us, can be dismantled, demolished—returned to where it all came from.

“To believe that each of Them will personally die is also to believe that Their system will die—that some chance of renewal, some dialectic, is still operating in History. To affirm Their mortality is to affirm Return. I have been pointing out certain obstacles in the way of affirming Return…”

From pages 539-40 of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

The sermon is from a Jesuit, one Father Rapier, and takes place in one of GR’s stranger episodes (which is really saying something, that adjective there). Before the sermon—a “Critical Mass,” our narrator takes unusual pains to make sure that we get it, that we understand that the Jesuit is here to preach “against return. Here to say that critical mass cannot be ignored. Once the technical means of control have reached a certain size, a certain degree of being connected one to another, the chances for freedom are over for good.”

Compare the Jesuit’s notation of “once, only once” to the passage on pages 412-13 on Kekulé, the snake that eats its own tale: “…a quote from Rilke: ‘Once, only once…’ One of Their favorite slogans. No return, no salvation, no Cycle—”. The sermon also echoes the They/We riff on page 521.

May 11, 1838 entry from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books

May 11, 1838.–At Boston last week. Items:–A young man, with a small mustache, dyed brown, reddish from its original light color. He walks with an affected gait, his arms crooked outwards, treading much on his toes. His conversation is about the theatre, where he has a season ticket,–about an amateur who lately appeared there, and about actresses, with other theatrical scandal.–In the smoking-room, two checker and backgammon boards; the landlord a great player, seemingly a stupid man, but with considerable shrewdness and knowledge of the world.– F—-, the comedian, a stout, heavy-looking Englishman, of grave deportment, with no signs of wit or humor, yet aiming at both in conversation, in order to support his character. Very steady and regular in his life, and parsimonious in his disposition,–worth $50,000, made by his profession.–A clergyman, elderly, with a white neck-cloth, very unbecoming, an unworldly manner, unacquaintance with the customs of the house, and learning them in a childlike way. A ruffle to his shirt, crimped.–A gentleman, young, handsome, and sea-flushed, belonging to Oswego, New York, but just arrived in port from the Mediterranean: he inquires of me about the troubles in Canada, which were first beginning to make a noise when he left the country,–whether they are all over. I tell him all is finished, except the hanging of the prisoners. Then we talk over the matter, and I tell him the fates of the principal men,–some banished to New South Wales, one hanged, others in prison, others, conspicuous at first, now almost forgotten.–Apartments of private families in the hotel,–what sort of domesticity there may be in them; eating in public, with no board of their own. The gas that lights the rest of the house lights them also, in the chandelier from the ceiling.–A shabby-looking man, quiet, with spectacles, at first wearing an old, coarse brown frock, then appearing in a suit of elderly black, saying nothing unless spoken to, but talking intelligently when addressed. He is an editor, and I suppose printer, of a country paper. Among the guests, he holds intercourse with gentlemen of much more respectable appearance than himself, from the same part of the country.–Bill of fare; wines printed on the back, but nobody calls for a bottle. Chairs turned down for expected guests. Three-pronged steel forks. Cold supper from nine to eleven P.M. Great, round, mahogany table, in the sitting-room, covered with papers. In the morning, before and soon after breakfast, gentlemen reading the morning papers, while others wait for their chance, or try to pick out something from the papers of yesterday or longer ago. In the forenoon, the Southern papers are brought in, and thrown damp and folded on the table. The eagerness with which those who happen to be in the room start up and make prize of them. Play-bills, printed on yellow paper, laid upon the table. Towards evening comes the “Transcript.”

“Mothers” — William Gaddis

“Mothers” by William Gaddis

When Ralph Waldo Emerson informed—or rather, perhaps, warned us—that we are what our mothers made us, we might dismiss it as received opinion and let it go at that, like the broken clock which is right twice a day, like the self-evident answer contained in Freud’s oft-quoted query “What do women want?” when, as nature’s handmaid, she must want what nature wants which is, quite simply, More. But which woman? Whose mother, Emerson’s? A woman so in thrall to religion that we confront another dead end; or Freud’s? or even one’s own, even mine, offering an opportune bit of wisdom to those of us engaged in the creative arts, where paranoia is almost an occupational hazard: “Bill, just try to remember,” she said, “there is much more stupidity than there is malice in the world,” an observation lavish with possibilities recalling Anatole France finding the fool more dangerous than the rogue because “the rogue does at least take a rest sometimes, the fool never.”

This is hardly to see stupidity and malice as mutually exclusive: look at your morning paper, where their combined forces explode exponentially (women and children first) from Bosnia to Belfast, unlike the international “intelligence community” so self-contained in its malice-free exercises that it generally ensnares only its own dubious cast of players. Of further importance is the distinction between stupidity and ignorance, since ignorance is educable, while stupidity’s self-serving mission is the cultivation and exploitation of ignorance, as politicians are keenly aware.

How, then, might Emerson’s mother have seen herself stumbling upon Thomas Carlyle’s vision of her son as a “hoary-headed and toothless baboon”? Or Freud’s, in the gross unlikelihood of her reading the Catholic World’s review of her son’s book Moses and Monotheism as “poorly written, full of repetitions . . . and spoiled by the author’s atheistic bias and his flimsy psychoanalytic fancies”? Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister dismissed as “sheer nonsense” by the Edinburgh Review and, a good century later, the hero of Saul Bellow’s Dangling Man ridiculed as a “pharisaical stinker” in Time magazine, John Barth’s The End of the Road recommended by Kirkus Reviews “for those schooled in the waste matter of the body and the mind,” and William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! shrugged off as the “final blowup of what was once a remarkable, if minor, talent” by The New Yorker magazine where, just forty years later, “a group of avant-garde critics has put forward the idea that books should be made unreadable. This movement has manifest advantages. Being unreadable, the text repels reviewers, critics, anthologists, academic literati, and other parasitical forms of life,” indicting the author of the novel J R wherein “to produce an unreadable text, to sustain this foxy purpose over 726 pages, demands rare powers. Mr. Gaddis has them.” “You’re a fool, a fool!” the distraught mother of Dostoevski’s ill-fated hero Nikolay Stavrogin cries out at the “parasitical forms of life” surrounding her. “You’re all ungrateful fools. Give me my umbrella!”

(“Mothers” is collected in The Rush to Second Place).

Watch a film about Thomas Pynchon, A Journey into the Mind of P

This 2002 documentary by Donatello Dubini and Fosco Dubini is kind of a mess, but it’s a fun mess. Interviews with old friends, like Jules Siegel, superfans and webdudes, and critics (George Plimpton shows up a few times), are interspliced with a lot of stock footage. The Residents’ fantastic pop appropriations from The Third Reich Rock n’ Roll help to stitch the movie together. The film occasionally indulges in a kind of obvious paranoid rambling, and the last section, detailing an attempt to photograph Thomas Pynchon (you remember that silly CNN report?) is not nearly as interesting as Allen Rush or other Pynchonians analyses…. Sort of a for completists only deal.

What the hell is Pynchon in Public Day?

Pynchon in Public Day is tomorrow, May 8th–that’s Pynchon’s birthday if you’re keeping score. (He’ll be 78 tomorrow. Last year I put together links for his auspicious 77th birthday).

For the past couple of years, I’ve seen the phrase Pynchon in Public pop up in my Twitter timeline, often as a hashtag. I had a (willfully) vague idea about what Pynchon in Public was all about–like, reading Pynchon publicly, posting the W.A.S.T.E. horn in public places, leaving books about. Making the secret sign. Etc.

But so and anyway: I’ve been reading or re-reading Pynchon more or less non-stop for the past two years, after diving for reasons I can’t recall into Against the Day, following that up with Mason & Dixon, and then going through The Crying of Lot 49 and Inherent Vice again. (In the deepest and most sincere spirit of my Pynchon-reading-experience, I abandoned Bleeding Edge twice during this time). I’m rereading Gravity’s Rainbow now after just having finished it (after years of false starts). Reading it again is like reading it for the first time, and as I progress (and sometimes retreat) through the Zone, I experience a sympathetic fragmentation, a scattering, a sense that the novel is consuming me. Another way of saying this is that Gravity’s Rainbow is a scary book, and all of Pynchon is scary in the sense that it’s all just one big book. It kinda sorta worms its way into the ear of one’s consciousness, wriggles (Ruggles?) behind the old brainpan, performs a paranoid song and dance routine. Other fun and games too.

Wait, what? Continue reading “What the hell is Pynchon in Public Day?”

This is not a review of Lydia Davis’s Can’t and Won’t

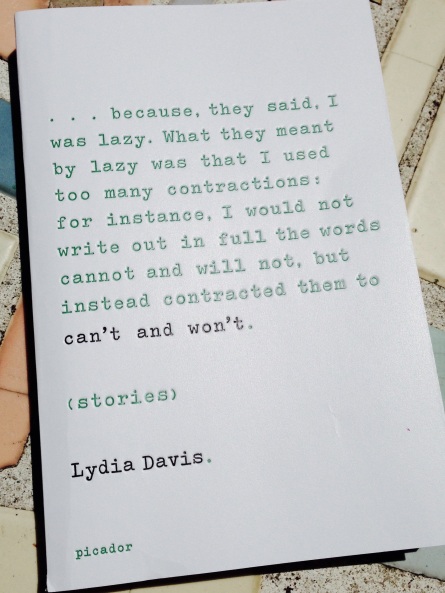

This is the part of the not-review where I include a picture I took of the book to accompany the not-review:

This is the part of the not-review where I briefly restage Lydia Davis’s publishing history to provide some context for readers new to her work.

This is the part of the not-review where I submit that anyone already familiar with Lydia Davis’s short fiction is likely to already hold an opinion on it that won’t (but could) be changed by Can’t and Won’t.

This is the part of the not-review where I dither pointlessly over whether or not the stories in Can’t and Won’t are actually stories or something other than stories.

This is the part of the not-review where I state that I don’t care if the stories in Can’t and Won’t are actually stories or something other than stories.

This is the part of the not-review where I explain that I have found a certain precise aesthetic pleasure in most of Can’t and Won’t that radiates from the savory contradictory poles of identification and alienation.

This is the part of the not-review where I cite an example of identification with Davis’s narrator-persona-speaker:

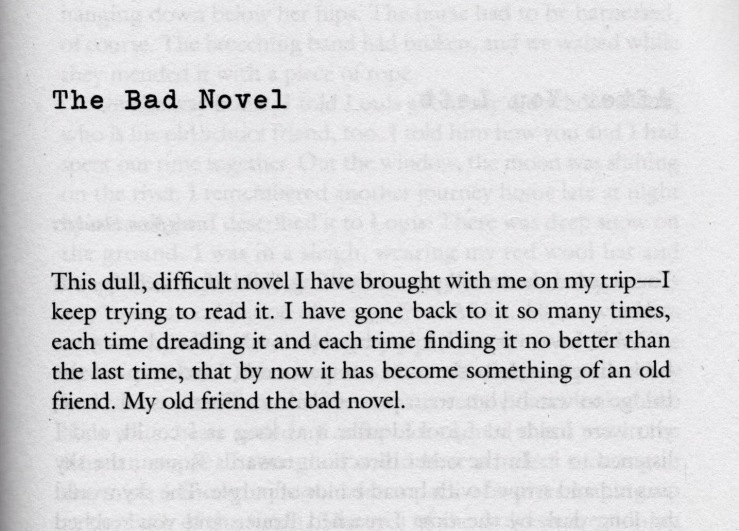

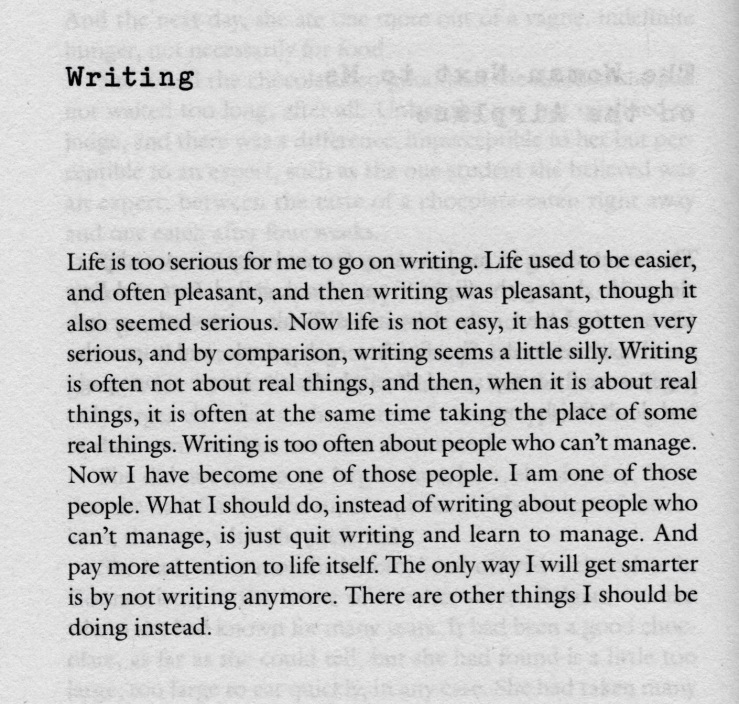

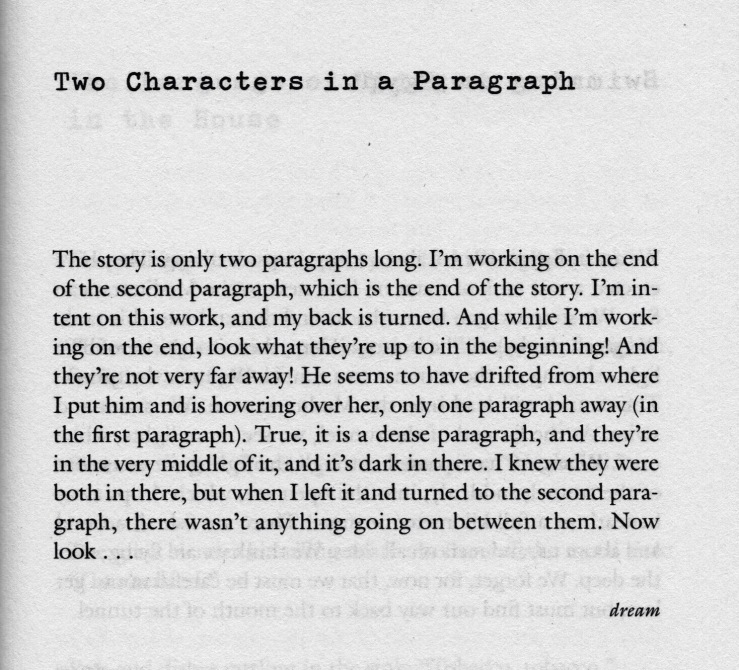

This is the part of the not-review where I claim that I used scans of the text to preserve the look and feel of Lydia Davis’s prose on the page.

This is the part of the not-review where I say that some of my favorite moments in Can’t and Won’t are Davis’s expressions of frustrated boredom with literature (or do I mean publishing?), like in the longer piece “Not Interested.”

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that Davis’s speaker-narrator-persona expresses frustration with the act of writing itself:

This is the part of the not-review where I dither pointlessly over distinctions between Davis the author and Davis the persona-speaker-narrator.

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that (previous dithering and frustration-with-writing aside) writing itself is a major concern of Can’t and Won’t:

This is the part of the not-review where I say that many of the stories in Can’t and Won’t are labeled dream, and I often found myself not really caring for these dreams (although I like the one above), but maybe I didn’t really care for the dreams because of their being tagged as dreams. (This is the part of the not-review where I point out that our eyes glaze over when anyone tells us their literal dreams).

This is the part of the not-review where I transition from stories tagged dream to stories tagged story from Flaubert, like this one:

This is the part of the not-review where I say how much I liked the stories from Flaubert stories in Can’t and Won’t.

This is the part of the not-review where I mention Davis’s translation work, but don’t admit that I didn’t make it past the first thirty pages of her Madame Bovary.

This is the part of the not-review where I needlessly reference my review of The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis and point out that that collection is not so collected now.

This is the part of the not-review where I pointlessly dither over post-modernism, post-postmodernism, and Davis’s place in contemporary fiction. (This is the part of the not-review where I needlessly cram in the names of other authors, like Kafka and Walser and Bernhard and Markson and Adler and Miller &c.).

This is the part of the not-review where I claim that nothing I’ve written matters because Davis makes me laugh (this is also the part of the not-review where I use the adverb “ultimately,” a favorite crutch):

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that Can’t and Won’t is not for everybody, but I very much enjoyed it.

This is the part of the not-review where I mention that the publisher is FS&G/Picador, and that the book is available in the usual formats.

Orson Welles on making fun of Ernest Hemingway

Check out Waywords and Meansigns, a musical adaptation of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

Biblioklept: What is Waywords and Meansigns?

Derek Pyle: Waywords and Meansigns is a collaborative music project recreating James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Seventeen different musicians from all around world have each taken a chapter of Finnegans Wake and set it to music, thereby creating an unabridged audio version of Finnegans Wake.

Finnegans Wake is an incredible book, but it’s notoriously difficult to read. One hope of the project is to create a version of the Wake that is accessible to newcomers — people can just listen to and enjoy the music. To maximize accessibility, we are distributing all the audio freely via our website. But the project does not only appeal to Wake newcomers — as we’ve seen so far, a lot of scholars and devoted readers are also finding Waywords and Meansigns an exciting way of interpreting and engaging with Joyce’s text.

In which I read Playboy for the Thomas Pynchon article

A couple of days ago I posted a brief excerpt from Jules Siegel’s March 1977 Playboy profile “Who is Thomas Pynchon… And Why Did He Take Off With My Wife?” The excerpt came from an excerpt posted on the Pynchon-L forum, but most of the article had been removed at the (apparent) request by Siegel. Several folks sent me the whole article though (thanks!) and I read it.

Siegel was briefly a Cornell classmate of Pynchon’s in 1954, and they remained friends (in Siegel’s recollection) for at least two decades after. During this time, Siegel claims that Pynchon wrote him dozens of letters, which were ultimately sold at auction (along with much of Siegel’s property) to help pay for a hip replacement. Material from the letters soak into Siegel’s sketch of Pynchon’s progress, along with several stoned/drunken adventures that would not be out of place in V. or Mason & Dixon or Gravity’s Rainbow, or really, any person’s young life.

A competitive anxiety reverberates under the piece. “We were friends, maybe at some points best friends, very much alike in some important ways,” Siegel writes. “We were both writers,” he boldly writes. Siegel reminds us that “In Mortality and Mercy in Vienna, Pynchon’s first published short story, the protagonist is one Cleanth Siegel,” but protests he doesn’t see himself in that hero.

The competitive anxieties culminate in the big reveal that (spoiler!) Thomas Pynchon had an affair with Siegel’s second wife Chrissie. There’s probably a Freudian reading we can append to the details that Siegel offers about Pynchon’s sexual prowess: “He was a wonderful lover, sensitive and quick, with the ability to project a mood that turned the most ordinary surroundings into a scene out of a masterful film—the reeking industrial slum of Manhattan Beach would become as seen through the eye of Antonioni, for example.”

Or maybe these unsexy details are just a sign of Playboy’s editorial hand. Wedged gracelessly between ads for vibrators and nude greeting cards, Siegel’s lines often reek of 1970’s Playboy’s rhetorical house style, a kind of frank-but-(attempted)-sensual glossiness that contrasts heavily with Pynchon’s own sex writing. At times I found myself reading Siegel’s prose in one of Will Ferrell’s more pompous accents.

Even worse is the casual sexism of the piece—which again, may be attributable to Playboy’s editors. Siegel, on his first wife (sixteen when he married her): “She was so wonderful a lover, generous and easily aroused, but I was too callow then to appreciate her.” Of his second wife: “It is easy to underestimate her intelligence, but it is a mistake. She is obviously too pretty to be serious, conventional wisdom would have you believe.” Of one of Pynchon’s girlfriends: “Susan has red hair and is breathtakingly beautiful, with the voluptuous body of a showgirl. Like Chrissie, she is much brighter than she looks.”

More interesting, obviously, are the (supposedly) real-life details that inform Pynchon’s fiction. Siegel notes some of the contents of Pynchon’s Manhattan Beach apartment: “A built-in bookcase had rows of piggy banks on each shelf and there was a collection of books and magazines about pigs.” Pigs, of course, are a major motif of Gravity’s Rainbow. Another detail that seems to connect to GR: “On the desk, there was a rudimentary rocket made from one of those pencil-like erasers with coiled paper wrappers that you unzip to expose the rubber. It stood on a base twisted out of a paper clip.” Siegel lets us know that he knocked the rocket down. Pynchon puts it back together; Siegel knocks it down again.

(Parenthetically: Siegel’s evocation of Pynchon’s Manhattan Beach days fits neatly into my picture of Inherent Vice).

In accounting details of Pynchon’s alleged affair with his wife, Chrissie, Siegel shares the following:

Once, out on the freeway, she told him that we had all gone naked at the commune, he professed to find that incredible and dared her to take off her blouse right there. She did. A passing truck hooted its horn in lewd applause. He loved her Shirley Temple impersonations—On the Good Ship Lollipop sung and danced like a kid at a birthday party. They talked about running away together.

It is hardly possible here not to recall the episode early in Gravity’s Rainbow wherein Jessica Swanlake removes her blouse in the car on a dare from Roger Mexico. Is Siegel daring the reader to extrapolate further? Extrapolation, paranoid connections—isn’t this part of Pynchonian fun?

In that spirit, I’ll close with my favorite moment from the article.

“You know the W.A.S.T.E. horn in The Crying of Lot 49? The symbol of the secret message service? Every weirdo in the world is on my wave length. You cannot understand the kind of letters I get. Someone wrote to tell me that the very same horn was the symbol of a private mail system in medieval times. I checked it out at the library. It’s true. But I made it up myself before the book was ever published, before I ever got that letter.”

The lines are supposedly from Pynchon himself. Siegel even puts them in quotation marks—so they must be real, right?

Selections from One-Star Amazon Reviews of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666

[Editorial note: Today is Roberto Bolaño’s birthday–he would’ve turned 62. The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews of his masterpiece 2666. To be clear, I am a huge fan of 2666—I’ve written about it extensively on this site. But I never posted a review on Amazon. More one-star Amazon reviews.].

***

Awful.

Boring!

Nothing.

No Point.

No Story.

No characters.

This is not a story.

Felt it was too dark.

endless culs-de-sac

There is no premise

Numbing dumbness.

As a Literature major,

incoherent and rambling

Disconnected and tedious.

The joke is on me, I guess.

written in a type of journalese

this novel (if it can be called that)

an obtuse novel with no real point.

I would rather stick forks in my eyes

stilted, awkward, and difficult to read

I would prefer to be boiled alive in oil.

900 pages of words that mean nothing.

multiple pages are spent describing dreams

delivers little if any enjoyment to the reader.

900 pages of distinctly non-literary masochism

I hated the spewing of authors I’d never heard of.

The writing or words are geared towards intellectuals.

Imagine this: you’re dreaming a dream that never ends.

it’s one of those pretentious books for pretentious people

a sprawling, formless, utterly pretentious bloated drudge

bloated streams of consciousness which negate themselves

no subtle meassage that is worthy of discussion or thought

I can see how this might have been written by a very ill man.

boring, repetitive, pointless, misogynistic, indulgent blather

I’ve never experienced a book which was so devoid of reward.

little or no substance in terms of an overall message or theme

a pointless study of odd obsessions and the meaningless of life

On xx date, the body of xxx was found, mutilated in the dumps.

I spent most of my time looking up defintions to 100’s of words.

this book is a GRUESOME and HORRIFICALLY VIOLENT book.

Bolano could not care less what the general public thinks of his book

has little of note to say about the meaning of life or the human condition

I am hard pressed to believe that the other reviewers even read this book.

The largest section of the book is basically 300+ pages of autopsy reports.

You will read the words “vaginally and anally raped” over and over and over

This book would make a great table leg, coaster, or booster seat for a small child. Continue reading “Selections from One-Star Amazon Reviews of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666”

Derek Pyle Discusses Waywords and Meansigns, an Unabridged Musical Adaptation of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

I recently talked to Derek Pyle about his project Waywords and Meansigns, which adapts James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake into a new musical audiobook. Derek worked for years as half of Jubilation Press. Printing the poems of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Thich Nhat Hanh, and William Stafford, Derek’s letterpress work can be found in the special collections of the New York Public Library, Brown University, and the Book Club of California. Derek co-founded Waywords and Meansigns in 2014 and became the project’s primary director in 2015. While living part-time in Western Massachusetts, Derek produces Waywords and Meansigns in eastern Canada.

Biblioklept: What is Waywords and Meansigns?

Derek Pyle: Waywords and Meansigns is a collaborative music project recreating James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Seventeen different musicians from all around world have each taken a chapter of Finnegans Wake and set it to music, thereby creating an unabridged audio version of Finnegans Wake.

Finnegans Wake is an incredible book, but it’s notoriously difficult to read. One hope of the project is to create a version of the Wake that is accessible to newcomers — people can just listen to and enjoy the music. To maximize accessibility, we are distributing all the audio freely via our website. But the project does not only appeal to Wake newcomers — as we’ve seen so far, a lot of scholars and devoted readers are also finding Waywords and Meansigns an exciting way of interpreting and engaging with Joyce’s text.

Biblioklept: How did the project come about?

DP: In 2014 I organized a party to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the publication of Finnegans Wake. To celebrate we decided to listen to Patrick Healy’s audiobook recording of Finnegans Wake, which is 20-odd hours long. The party, as you can imagine, lasted all weekend — we actually listened to Johnny Cash’s unabridged reading of the New Testament that weekend too. There was very little sleep, and fair amount of absinthe.

A lot of people really rag on Healy’s recording, because it’s read at breakneck speed. I actually like it though — he creates a very visceral flood of experience, which is one way of reading, or interpreting, Finnegans Wake. But during the party I started wondering about other ways you could perform the text, and that’s when I came up with the idea of approaching musicians to create a new kind of audiobook.

As it turns out, a lot of people seemed to think my idea was a good one. We’ve had no shortage of musicians willing to contribute, including some really cool cats like Tim Carbone of Railroad Earth and bassist Mike Watt, who currently plays in Iggy Pop’s band The Stooges.

Biblioklept: Watt rules! I love the Minutemen and his solo stuff. He seems like a natural fit for this kind of project, as so much of his music is based around story telling. I imagine the musicians involved are composing the music themselves…are they also recording it themselves?

DP: Yeah, it’s very cool to have Watt on board. Turns out he’s a huge fan of Joyce — he recorded a track for Fire Records in 2008, for an album of various musicians turning the poems of Joyce’s Chamber Music into songs. Mary Lorson, of the bands Saint Low and Madder Rose, also played on that Fire Records album, and she’s collaborating with author Brian Hall for our project.

To answer your question, yes, all the musicians are recording their own chapters. Since we have contributors from all around the world — from Berlin to Amsterdam to British Columbia — it would be a logistical nightmare to figure out where and when to record everyone. Not to mention the cost of it. One of the really cool things, I think, about this project — for everyone, it’s a labor of love. No one is making a profit, off any of this. People are just doing it because they love Joyce, or they’re obsessed with Finnegans Wake, or it just seems like a fun challenge to think creatively in this unique way. Either way it’s a pursuit of passion. That’s why we will distribute all the audio freely. There’s this phrase in Finnegans Wake, “Here Comes Everybody!” We’re having fun with Finnegans Wake and everybody is invited to the party. Continue reading “Derek Pyle Discusses Waywords and Meansigns, an Unabridged Musical Adaptation of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake”

Reflect on these two quite brilliant thoughts (Georges Perec)

“The Girls of Herland” — Charlotte Perkins Gilman

“The Girls of Herland,” below, is Chapter 8 of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 novel Herland, a feminist utopian novel that was serialized during its author’s lifetime, but not published in one volume until 1979. This chapter can, I believe, stand alone or serve even as an introduction even to Herland, depsite coming rather late in the text, but readers who wish more context/want the whole thing can legally download Herland via Project Gutenburg.

***

“The Girls of Herland”

by

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

At last Terry’s ambition was realized. We were invited, always courteously and with free choice on our part, to address general audiences and classes of girls.

I remember the first time—and how careful we were about our clothes, and our amateur barbering. Terry, in particular, was fussy to a degree about the cut of his beard, and so critical of our combined efforts, that we handed him the shears and told him to please himself. We began to rather prize those beards of ours; they were almost our sole distinction among those tall and sturdy women, with their cropped hair and sexless costume. Being offered a wide selection of garments, we had chosen according to our personal taste, and were surprised to find, on meeting large audiences, that we were the most highly decorated, especially Terry.

He was a very impressive figure, his strong features softened by the somewhat longer hair—though he made me trim it as closely as I knew how; and he wore his richly embroidered tunic with its broad, loose girdle with quite a Henry V air. Jeff looked more like—well, like a Huguenot Lover; and I don’t know what I looked like, only that I felt very comfortable. When I got back to our own padded armor and its starched borders I realized with acute regret how comfortable were those Herland clothes.

We scanned that audience, looking for the three bright faces we knew; but they were not to be seen. Just a multitude of girls: quiet, eager, watchful, all eyes and ears to listen and learn.

We had been urged to give, as fully as we cared to, a sort of synopsis of world history, in brief, and to answer questions. Continue reading ““The Girls of Herland” — Charlotte Perkins Gilman”

Peter Brook’s (Condensed) Hamlet

The Bard and the Bird (Shakespeare Portrait) — Bill Sienkiewicz