A note to readers new to Infinite Jest

David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel Infinite Jest poses rhetorical, formal, and verbal challenges that will confound many readers new to the text. The abundance of (or excess of) guides and commentaries on the novel can perhaps have the adverse and unintentional consequence of making readers new to Infinite Jest believe that they can’t “get it” without help. Many of the online analyses and resources for Infinite Jest are created by and targeted to readers who have finished the novel or are rereading the novel. While I’ve read many insightful and enlightening commentaries on the novel over the years, my intuition remains that the superabundance of analysis may have the paradoxical effect of actually impeding readers new to the text. With this in mind, I’d suggest that first-time readers need only a dictionary and some patience.

Infinite Jest is very long but it’s not nearly as difficult as its reputation suggests. There is a compelling plot behind the erudite essaying and sesquipedalian vocabulary. That plot develops around three major strands which the reader must tie together, with both the aid of—and the challenge of—the novel’s discursive style. Those three major plot strands are the tragic saga of the Incandenzas (familial); the redemptive narrative of Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House, with Don Gately as the primary hero (sociocultural); and the the schemes of the Québécois separatists (national/international/political). An addictive and thus deadly film called Infinite Jest links these three plots (through discursive and byzantine subplots).

Wallace often obscures the links between these plot strands, and many of the major plot connections have to be intuited or outright guessed. Furthermore, while there are clear, explicit connections between the plot strands made for the reader, Wallace seems to withhold explicating these connections until after the 200-page mark. Arguably, the real contours of the Big Plot come into (incomplete) focus in a discussion between Hal Incandenza and his brother Orin in pages 242-58. Getting to this scene is perhaps a demand on the patience of many readers. And, while the scene by no means telegraphs what happens in IJ, it nonetheless offers some promise that the set pieces, riffs, scenes, lists, and vignettes shall add up to Something Bigger.

Some of those earliest set pieces, riffs, scenes, lists, and vignettes function almost as rhetorical obstacles for a first-time reader. The novel’s opening scene, Hal Incandenza’s interview with the deans at the University of Arizona, is chronologically the last event in the narrative, and it dumps a lot of expository info on the reader. It also poses a number of questions or riddles about the plot to come, questions and riddles that frankly run the risk of the first-time reader’s forgetting through no fault of his own.

The second chapter of IJ is relatively short—just 10 pages—but it seems interminable, and it’s my guess that Wallace wanted to make his reader endure it the same way that the chapter’s protagonist–Erdedy, an ultimately very minor character—must endure the agonizing wait for a marijuana delivery. The chapter delivers the novel’s themes of ambivalence, desire, addiction, shame, entertainment, “fun,” and secrecy, both in its content and form. My guess is that this where a lot of new readers abandon the novel.

The reader who continues must then work through 30 more pages until meeting the novel’s heart, Don Gately, but by the time we’ve met him we might not trust just how much attention we need to pay him, because Wallace has shifted through so many other characters already. And then Gately doesn’t really show up again until, like, 200 pages later.

In Infinite Jest, Wallace seems to suspend or delay introducing the reading rules that we’ve been trained to look for in contemporary novels. While I imagine this technique could frustrate first-time readers, I want to reiterate that this suspension or delay or digression is indeed a technique, a rhetorical tool Wallace employs to perform the novel’s themes about addiction and relief, patience and plateaus, gratitude and forgiveness.

Where is a fair place to abandon Infinite Jest?

I would urge first-time readers to stick with the novel at least until page 64, where they will be directed to end note 24, the filmography of J.O. Incandenza (I will not even discuss the idea of not reading the end notes. They are essential). Incandenza’s filmography helps to outline the plot’s themes and the themes’ plots—albeit obliquely. And readers who make it to the filmography and find nothing to compel them further into the text should feel okay about abandoning the book at that point.

What about a guide?

There are many, many guides and discussions to IJ online and elsewhere, as I noted above. Do you really need them? I don’t know—but my intuition is that you’d probably do fine without them. Maybe reread Hamlet’s monologue from the beginning of Act V, but don’t dwell too much on the relationship between entertainment and death. All you really need is a good dictionary. (And, by the way, IJ is an ideal read for an electronic device—the end notes are hyperlinked, and you can easily look up words as you read).

Still: Two online resources that might be useful are “Several More and Less Helpful Things for the Person Reading Infinite Jest,” which offers a glossary and a few other unobtrusive documents, and “Infinite Jest: A Scene-By-Scene Guide” which is not a guide at all, but rather a brief series of synopses of each scene in the novel, organized by page number and year; my sense is that this guide would be helpful to readers attempting to delineate the novel’s nonlinear chronology—however, I’d advise against peeking ahead. After you read you may wish to search for a plot diagram of the novel, of which there are several. But I’d wait until after.

An incomplete list of motifs readers new to Infinite Jest may wish to attend to

The big advantage (and pleasure) of rereading Infinite Jest is that the rereader may come to understand the plot anew; IJ is richer and denser the second go around, its themes showing brighter as its formal construction clarifies. The rereader is free to attend to the imagery and motifs of the novel more intensely than a first-time reader, who must suss out a byzantine plot propelled by a plethora of characters.

Therefore, readers new to IJ may find it helpful to attend from the outset to some of the novel’s repeated images, words, and phrases. Tracking motifs will help to clarify not only the novel’s themes and “messages,” but also its plot. I’ve listed just a few of these motifs below, leaving out the obvious ones like entertainment, drugs, tennis (and, more generally, sports and games), and death. The list is in no way definitive or analytic, nor do I present it as an expert; rather, it’s my hope that this short list might help a reader or two get more out of a first reading.

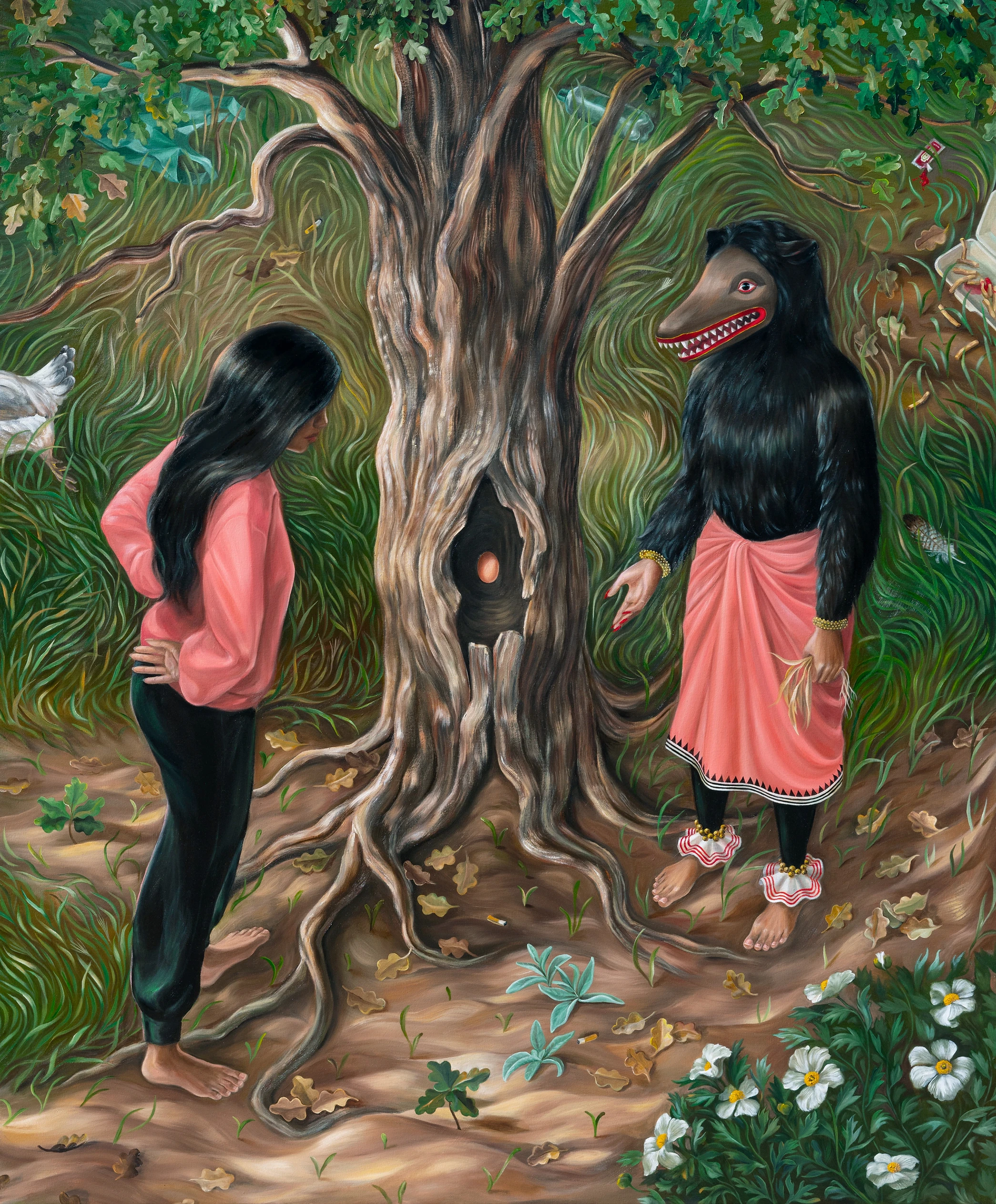

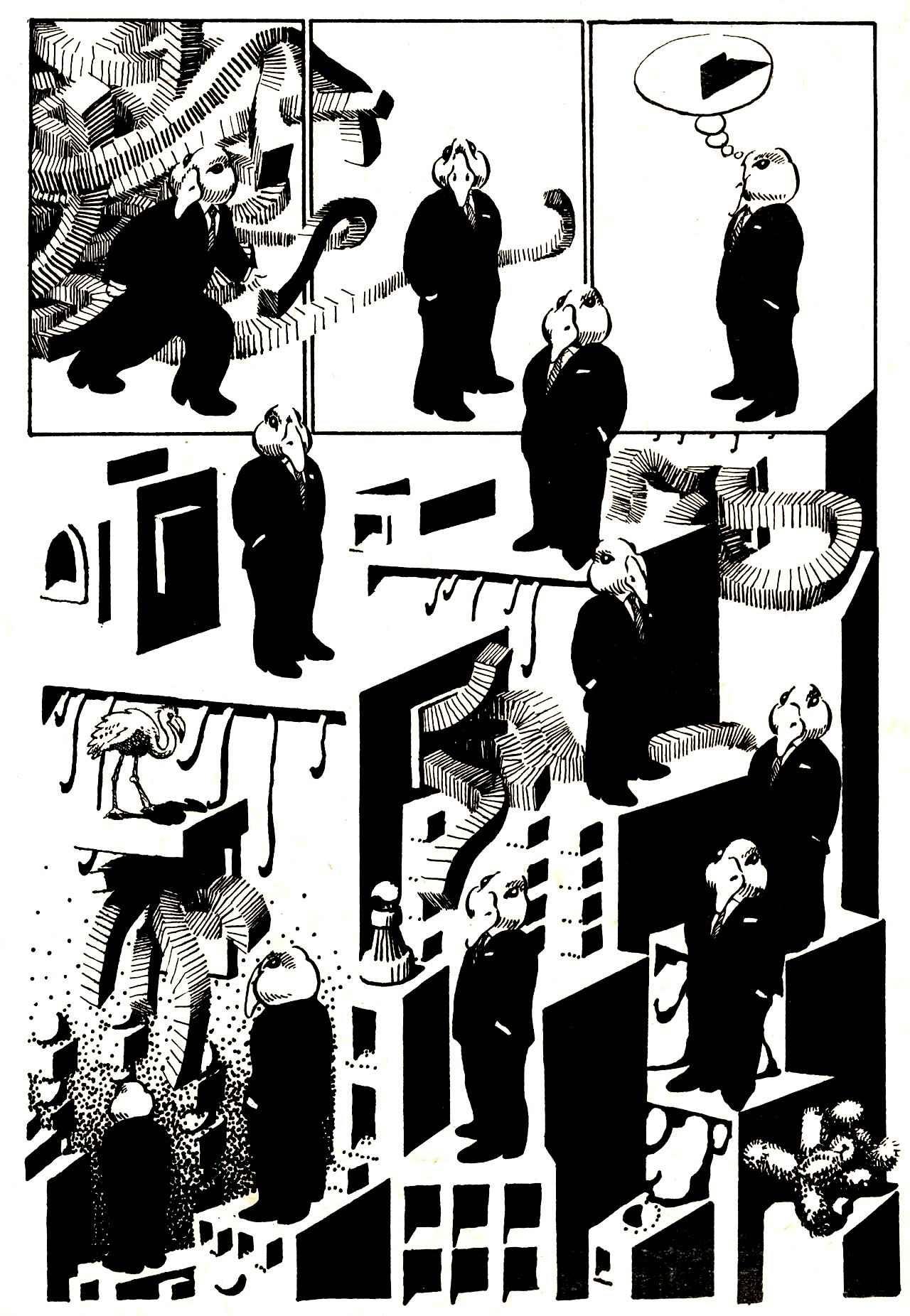

Heads

Cages

Faces

Masks

Teeth

Cycles

Maps

Waste

Infants

Pain

Deformities

Subjects

Objects

One final note

Infinite Jest is a rhetorical/aesthetic experience, not a plot.

[Ed. note: Biblioklept first posted a version of this note in the summer of 2015. Today marks the thirtieth anniversary of Infinite Jest’s publication. Wallace’s novel remains underread by overtalkers].