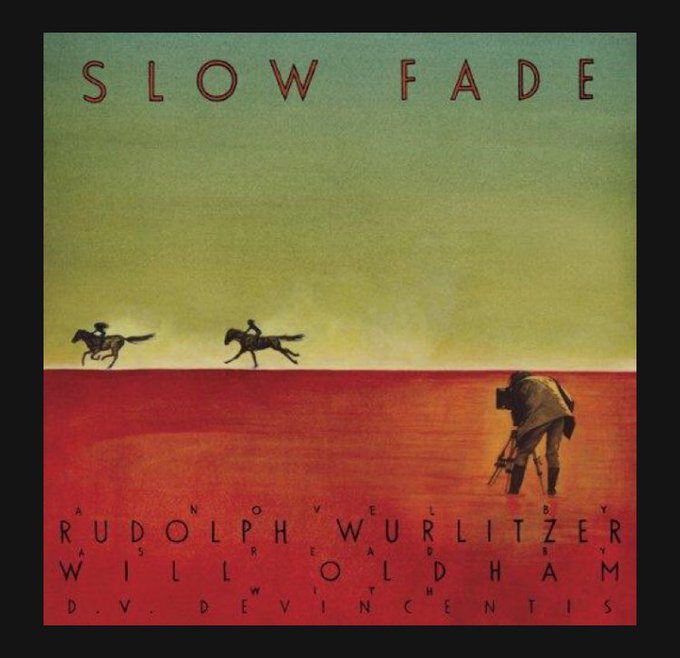

So I just finished auditing Drag City’s audiobook version of Rudolph Wurlitzer’s 1984 novel Slow Fade. I finished on yet-another-walk-around-the-block, this time for the express reason of ending it. The novel is read by Will Oldham with actor D.V. DeVincentis (who perhaps unfairly got left out of the headline—but no offense to DeVincentis, he has not been a hero of mine since I was like fourteen).

I read Rudolph Wurlitzer’s first novel Nog a few weeks ago and didn’t really like it.

I read it because one of my heroes Thomas Pynchon blurbed it (do you sense a terrible propensity toward hero worship in me?). A bit of googling-it-up revealed that one of Wurlitzer’s later novels Slow Fade was reprinted by Drag City back in 2011, along with an audiobook version recorded by the singer/songwriter/actor/guy Will Oldham. This kind of shocked me—I’ve been a fan of Will Oldham and Drag City since 1994, when I and three other dudes pooled our money to order CDs, LPs, and 7″s from the fledgling label and tape the music for each other. (I got the Hey Drag City comp. I guess it must’ve been sophomore year of high school. I ended up using a line from “For the Mekons et. al.” by Will Oldham’s band Palace Brothers as my senior quote. (The quote was “If you can forget how to ride a book you have had a good teacher,” which I thought was like, super zen, but the yearbook staff fucked it up and rendered it as “If you can forget how to ride a book you have had a teacher.” My parents bought the yearbook declaring I would love to pore over it; I threw it away maybe 18 years ago and should’ve thrown it away years before that.))

Man! I’ve really gotten far without discussing the novel. Good for me. I started with the headline instead of the content, which seems a terrible thing to do to the reader. (Look, I’ve been drinking, which is not a good idea.)

Every one in Slow Fade is drinking (and drugging and fucking, and trying to get rock’n’rolling—but mostly they are despairing, grieving, blowing up what’s left of their lives.) The novel centers around a megalomaniac film director, Wesley Hardin, a kind of totemic holdover of Old Hollywood-into-New-Hollywood, a maker of rough Westerns likened to John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Sam Peckinpah. (Wurlitzer wrote the script for Peckinpah’s 1973 film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Everything meaningful in this riff is probably parenthetical at this point.)

I marked the audiobook to quote from it but in the spirit of Wurlitzer’s novel and Our Uncertain Times I’m on my third tequila drink and I really can’t be bothered. He can turn a phrase or two or three, but there are some crutches in there, some clunkers. (And maybe some zappers: Okay—in the spirit of the parentheses doing the real work: Wurlitzer gives us the image of “a thin slice of moon that hung up in the sky like a whore’s earring,” a simile that is simultaneously terrible and great.)

Ah! But what is it about? you ask.

In the words of Hardin’s (much younger) wife Eveyln—

“It’s about a man and his wife looking for the man’s sister who has disappeared in India. So far they haven’t found her.

Well—okay—that’s actually Evelyn’s description of the screenplay that Wesley Hardin’s son Walker Hardin is writing with the opportunistic roadie/keyboardist/hustler AD Ballou (Assistant Director Balloo?), who gets shot in the eye with an arrow when he rides a stolen horse into Wesley Hardin’s current film at the beginning of Slow Fade. (Wesley and Walker both go on to blow up their lives after this moment, while AD saves his.)

In the meantime, opportunistic folk opportune around Wesley, who flames out in spectacular, globetrotting fashion. The novel plays out as a series of bad decisions, oedipal impulses, and drug-addled romps. Wesley’s treacherous cameraman Sidney tries to make his own film about the aging auteur’s implosion, leading to a postmodern film-within-a-film-within-a-film-script-within-a-novel structure that is hardly as cute as I might’ve just posited. There are heroes and villains, but mostly villains.

(Slow Fade mostly made me think of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, Malcom Lowry’s Under the Volcano, and HBO’s Succession. My mental eye couldn’t decide if Wesley was Brian Cox or John Huston.)

Will Oldham’s narration is fantastic—honest and raw, unaffected but also acted with the achieved naturalism of a narrator who understands the novel and doesn’t need to ham it up. D.V. DeVincentis reads the sections of the novel that take the form of the film script that AD and Walker are writing, a production device that adds dynamism to the auditing experience.

I liked Slow Fade a lot more than Wurlitzer’s first novel Nog, which oozed with the abject excess of the sixties, always gazing inward. Slow Fade isn’t without its problems—the women have agency but are underwritten, and the sex scenes are at best plot points and at worst embarrassing. The novel seems a companion pieces to Pynchon’s Vineland, a riff on the failure of the Western Sixties. And also like Nog, Slow Fade reads like an encomium for the American Dream of the West. Here though, the Western dream of space, expansion, and destiny manifesting itself into the Hollywood dream seeks an Eastern outlet, a metaphysical escape hatch into India, Nepal, exotic enlightenment. But that’s all on the characters. Wurlitzer’s ultimate viewpoint sings far more cynical. Slow Fade depicts a world of opportunists trying to drape dreams over any dupe that steps in their general direction. The results are tragic, ugly, and cynical. Recommended.

When the kind folks at Audible offered me a review opportunity, I thought I’d take another shot at Murakami. His new novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage is short enough, I reasoned, for me to, y’know, not abandon it.

When the kind folks at Audible offered me a review opportunity, I thought I’d take another shot at Murakami. His new novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage is short enough, I reasoned, for me to, y’know, not abandon it.  I’ve used Tim O’Brien’s short story “The Things They Carried” in the classroom for so many years now that I’ve perhaps become immune to any of the tale’s rhetorical force.Trekking through the story again with a new group of students can occasionally turn up new insights—mostly these days from veterans going back to school after tours in Iraq and Afghanistan—but for the most part, the story “The Things They Carried” is too blunt in its symbols, too programmatic in its oppositions of the physical and metaphysical, too rigid in its maturation plot. There’s no mystery to it, unlike other oft-anthologized stories which can withstand scores of rereadings (I think of Hawthorne or O’Connor here; when I reread “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” for example, I always understand it or misunderstand it in a new, different way).

I’ve used Tim O’Brien’s short story “The Things They Carried” in the classroom for so many years now that I’ve perhaps become immune to any of the tale’s rhetorical force.Trekking through the story again with a new group of students can occasionally turn up new insights—mostly these days from veterans going back to school after tours in Iraq and Afghanistan—but for the most part, the story “The Things They Carried” is too blunt in its symbols, too programmatic in its oppositions of the physical and metaphysical, too rigid in its maturation plot. There’s no mystery to it, unlike other oft-anthologized stories which can withstand scores of rereadings (I think of Hawthorne or O’Connor here; when I reread “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” for example, I always understand it or misunderstand it in a new, different way). James Joyce’s Ulysses might seem like a prohibitively difficult book, but it’s not as hard to read as its reputation suggests. There are

James Joyce’s Ulysses might seem like a prohibitively difficult book, but it’s not as hard to read as its reputation suggests. There are

The plot of Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando hangs on two key conceits: the title character transforms from male to female; the title character is immortal. Orlando has been a staple of gender studies courses since before such courses existed, and is in many ways the pioneer text (or one of the pioneer texts) of an entire genre. And that’s great and all—there are plenty of stunning passages where Woolf has her character explore what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman and how power and identity and all that good stuff fits in—but what I enjoyed most about Orlando was its rambling, satirical structure.

The plot of Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando hangs on two key conceits: the title character transforms from male to female; the title character is immortal. Orlando has been a staple of gender studies courses since before such courses existed, and is in many ways the pioneer text (or one of the pioneer texts) of an entire genre. And that’s great and all—there are plenty of stunning passages where Woolf has her character explore what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman and how power and identity and all that good stuff fits in—but what I enjoyed most about Orlando was its rambling, satirical structure.

Started a new audiobook: Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, read competently by Simon Slater. Wolf Hall tells the familiar story of Henry VIII, only Mantel focuses (at least so far) mostly on Thomas Crownwell and Cardinal Wolsey. Most of the men in the story have the first name “Thomas.” I’m not particularly interested in the Tudor saga but I’m enjoying Mantel’s novel so far–its clean, precise style, its pacing, and, particularly Mantel’s sparing use of details. Historical novels sometimes succumb to the weight of the author’s passion with her subject. Thankfully, Mantel does not overload her prose with superfluity; instead she appoints detail in her narrative with care and precision, giving character and plot room to grow. Good dialogue too. More later.

Started a new audiobook: Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, read competently by Simon Slater. Wolf Hall tells the familiar story of Henry VIII, only Mantel focuses (at least so far) mostly on Thomas Crownwell and Cardinal Wolsey. Most of the men in the story have the first name “Thomas.” I’m not particularly interested in the Tudor saga but I’m enjoying Mantel’s novel so far–its clean, precise style, its pacing, and, particularly Mantel’s sparing use of details. Historical novels sometimes succumb to the weight of the author’s passion with her subject. Thankfully, Mantel does not overload her prose with superfluity; instead she appoints detail in her narrative with care and precision, giving character and plot room to grow. Good dialogue too. More later. I got a review copy of Adam Schwartzmann’s début novel Eddie Signwriter last week and haven’t had a good chance to read any of it until today. The novel tells the story of Kwasi Edward Michael Dankwa aka Eddie Signwriter, who journeys from his native Ghana to Senegal, and then to France, where he takes up a new life as an illegal immigrant in Paris. The story opens in a burst of action. Nana Oforwiwaa, a village elder has died and authorities are blaming Kwasi. So far, I find Schwarzmann’s prose a bit heavy. Sentences need pruning–too many redundant verbs and clauses in his sentences for my taste. Eddie Signwriter is better when Schwartzmann moves the narrative of young Kwasi along in shorter, declarative sentences. Eddie Signwriter is available now from

I got a review copy of Adam Schwartzmann’s début novel Eddie Signwriter last week and haven’t had a good chance to read any of it until today. The novel tells the story of Kwasi Edward Michael Dankwa aka Eddie Signwriter, who journeys from his native Ghana to Senegal, and then to France, where he takes up a new life as an illegal immigrant in Paris. The story opens in a burst of action. Nana Oforwiwaa, a village elder has died and authorities are blaming Kwasi. So far, I find Schwarzmann’s prose a bit heavy. Sentences need pruning–too many redundant verbs and clauses in his sentences for my taste. Eddie Signwriter is better when Schwartzmann moves the narrative of young Kwasi along in shorter, declarative sentences. Eddie Signwriter is available now from