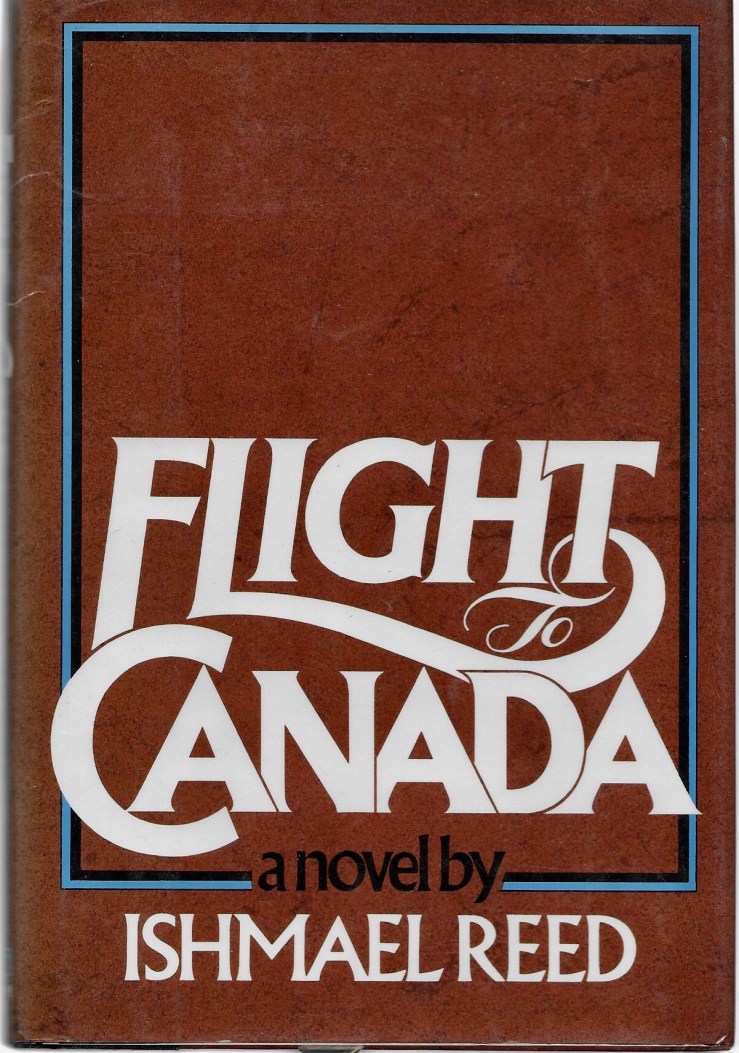

I read Ishmael Reed’s 1976 novel Flight to Canada over the last few days of 2019. I enjoyed the book tremendously, even as it made me dizzy at times with its frenetic, zany achronological satire of the American Civil War.

What is it about?

Flight to Canada features a number of intersecting plots. One of these plots follows the ostensible protagonist of the novel, former slave Raven Quickskill, who escapes the Swille plantation in Virginia. Along with two other former slaves of the Swille plantation, Quickskill makes his way far north to “Emancipation City” where he composes a poem called “Flight to Canada,” which expresses his desire to escape America completely. The aristocratic (and Sadean) Arthur Swille simply cannot let “his property run off with himself,” and sends trackers to find Quickskill and the other escapees, Emancipation Proclamation be damned. On the run from trackers, Quickskill jumps from misadventure to misadventure, eventually reconnecting his old flame, an Indian dancer named Quaw Quaw (as well as her husband, the pirate Yankee Jack). Back at Swille’s plantation Swine’rd, several plots twist around, including a visit by Old Abe Lincoln, a sadistic episode between Lady Swille and her attendant Mammy Barracuda, and the day-to-day rituals of Uncle Robin, a seemingly-compliant “Uncle Tom” figure who turns out to be Reed’s real hero in the end.

(And oh, Quickskill makes it to Canada in the end. Now, whether or not he wants to stay there after he gets there…)

There’s a whole lot more in the book, too. It’s difficult to summarize—like the majority of the other seven novels I’ve read by Reed, Flight to Canada isn’t so much a work of plot and character development as it is a jazzy extemporization of disparate themes and motifs. Reed’s novel is about slavery and freedom, war and aesthetics, perspective and time, and how history gets told and taught to future.

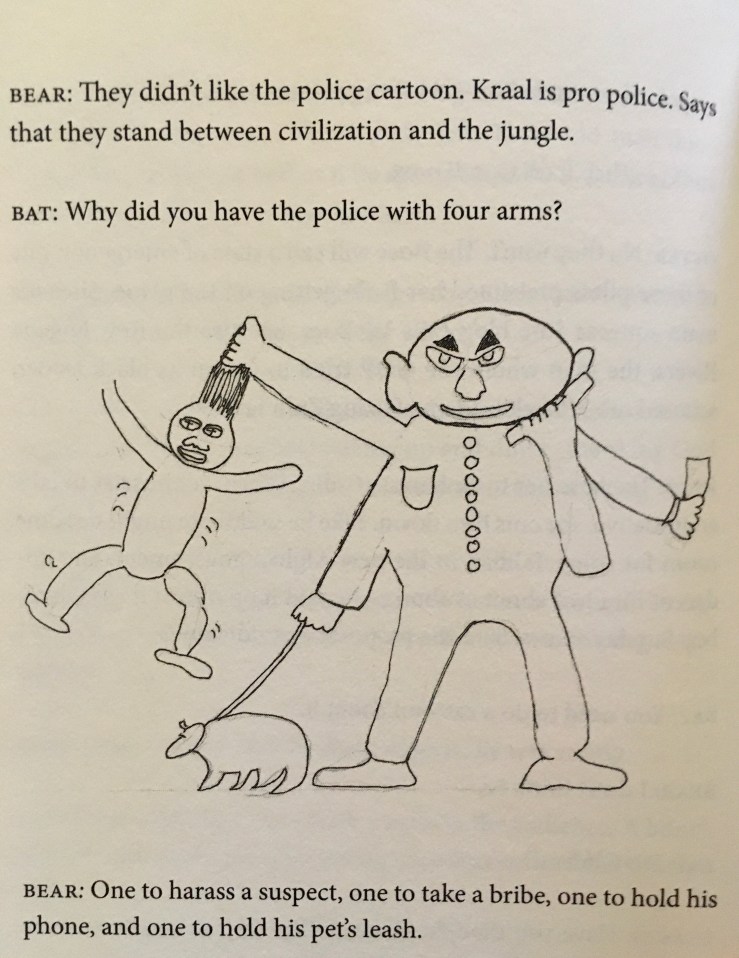

As a means to satirize not just the Civil War but also how we read and write and portray the Civil War, Reed collapses time in Flight to Canada. As novelist Jerome Charyn points out in his contemporary review of the novel in The New York Times,

Reed has little use for statistical realities. He is a necromancer, a believer in the voodoos of art. Time becomes a modest, crazy fluid in Reed’s head, allowing him to mingle events of the last 150 years, in order to work his magic. We have Abe Lincoln and the Late Show, slave catchers and “white ‐ frosted Betty Crocker glossy cake,” Jefferson Davis and Howard K. Smith. Every gentleman’s carriage is equipped with “factory climate‐control air conditioning, vinyl top, AM/FM stereo radio, full leather interior, power‐lock doors, six‐way power seat, power windows, whitewall wheels, door‐edge guards, bumper impact strips, rear defroster and softglass.”

Reed’s achronological gambit allows him to bring figures from any time period into the narrative, no questions asked. Edgar Allan Poe is there, even though he died over a decade before the war began. No matter. Our narrator claims early on that Poe was “the principal biographer of that strange war…Poe got it all down. Poe says more in a few stories than all of the volumes by historians.” Lord Byron shows up too, as do Charles I of England and the Marquis de Sade. There are contemporary figures of the Civil War era there too, of course—Harriet Beecher Stowe (whom Reed takes to task repeatedly), Frederick Douglass, and the writer William Wells Brown, whom Quickskill meets in a surprisingly moving scene (Quickskill says that Brown is his hero and that his novel Clotel was the inspiration for “Flight to Canada”). The fictional characters of Flight to Canada discuss or interact with these historical figures in such a way to continually critique not just the words and deeds of the historical figures, but the very way we frame and narrativize those words and deeds.

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all:

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all:

Booth, America’s first Romantic Assassin. They replay the actual act, the derringer pointing through the curtains, the President leaning to one side, the FIrst Lady standing, shocked, the Assassin leaping from the balcony, gracefully, beautifully, in slow motion. They promise to play it again on the Late News. When the cameras swing back to the Balcony, Miss Laura Keene of Our American Cousins is at Lincoln’s side “live.” Her gown is spattered with brain tissue. A reporter has a microphone in Mary Todd’s face.

“Tell us, Mrs. Lincoln, how do you feel having just watched your husband’s brains blow out before your eyes?”

(In a very Reedian move, the live assassination plays out during a sex scene between Quickskill and Quaw Quaw. The TV is always on in America, even during sex.)

Reed’s rhetorical distortions in depicting the Lincoln assassination are both grotesque and comic. Not only can we imagine a reporter doing the same in 1976, when Flight to Canada was published, we can imagine the same crass, exploitative handling today. Technology might have changed but people really haven’t

In his review, Jerome Charyn, begins by pointing out that 1976 is the American Bicentennial, something that simply did not entire my mind while reading Flight to Canada. Reed’s novel’s publication is appropriate and timely, and breaks “through the web of historical romance” (in the words of Charyn) that hangs over the “chicanery, paranoia and violence underlying most of our ‘democratic vistas.'”

Concluding his review, Charyn writes,

Flight to Canada could have been a very thin book, an unsubtle catalogue of American disorders. But Reed has the wit, the style, and the intelligence to do much more than that. The book explodes. Reed’s special grace is anger. His own sense of bewilderment deepens the comedy, forces us to consider the sad anatomy of his ideas. Flight to Canada is a hellish book with its own politics and a muscular, luminous prose. It should survive.

Books don’t survive of course; rather, they are always in the process of surviving. Books are either read, or not read. Flight to Canada should be read because it is witty and angry and unique and smart, and its critique of American history (and how we narrativize and aestheticize American history) is as vital and necessary today as it was nearly a half century ago.

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all:

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all: