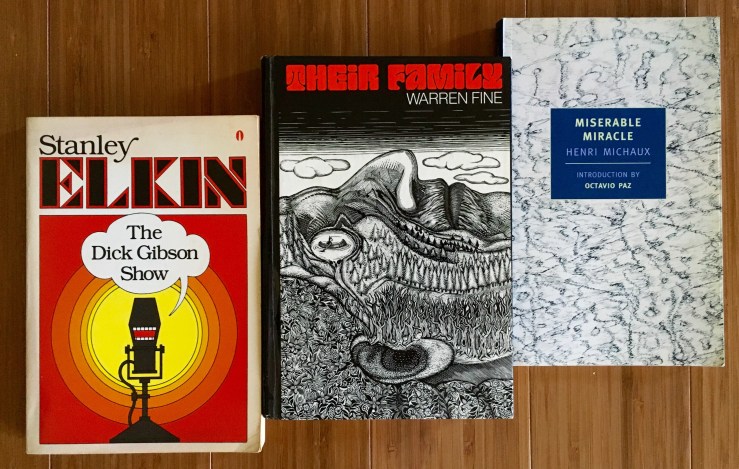

I swung by my favorite used bookstore this afternoon; it’s right near the grocery store and I needed to pick up some mint and some ricotta. I was hoping to pick up Elena Ferrante’s novel My Brilliant Friend at the bookstore. I started the audiobook of My Brilliant Friend today, after finishing the audiobook of Adrian Jones Pearson’s novel Cow Country this weekend. (Full review of Cow Country forthcoming but a real quick review: great performance/reading of a very strange book which I enjoyed very much, but which I also suspect will have very limited appeal. Cow cult classic to come). But so anyway, I’m really digging the Ferrante, and decided I wanted to obtain a physical copy to reread passages (and maybe share some on this blog). My store had several copies of four of Ferrante’s novels–but no Friend. While scanning the F section, my eye alighted (alit?) on a strange-looking hardback spine—Warren Fine’s Their Family. I turned it around and the cover…well, I knew I was gonna leave with it. Knopf, 1972—a few years before Gordon Lish was to become editor there, sure, but interesting bona fides I suppose. Fine does not seem to be beloved by anyone on the internet, and his books seem to have failed to go into second printings of any kind. The Fs are near the Es, and I glanced over the works of Mr. Stanley Elkin, who has his own section there, somehow. I finally broke through the second chapter of his novel The Franchiser this weekend (it’s all unattributed dialog, that chapter, sorta like Gaddis’s JR); I’m really digging The Franchiser now that I’ve tuned into the voice. (It also helps to not try reading it exclusively at night after too many bourbons or wines). Again, the spine of the novel looked interesting so I flipped The Dick Gibson Show around and, again, I knew I was gonna leave with it. Henri Michaux’s Miserable Miracle I found in the “Drugs” section—which I was not perusing (because I am no longer 19)—well I guess I was perusing it, but that’s only because it happens to be right next to this particular bookshop’s collection of Black Sparrow Press titles, which I always scan over. Anyway, the Michaux’s Miserable Miracle was turned face out; NYRB titles always deserve a quick scan, and the cover reminded me of a Cy Twombly painting. Flicking through it revealed a strange structure, full of marginal side notes and doodles and diagrams and drawings. And oh, it’s about a mescaline trip, I think. You can actually read it here, but this version is missing all the drawings and sidenotes.

Oh, and so then I forgot to go pick up the ricotta and the mint.

Fractured Karma by Tom Clark. First edition trade paperback from Black Sparrow Press. Design by Barbara Martin. The cover painting, Waiting Room for the Beyond, is by John Register. This is the first Tom Clark book I read. Amazing.

Fractured Karma by Tom Clark. First edition trade paperback from Black Sparrow Press. Design by Barbara Martin. The cover painting, Waiting Room for the Beyond, is by John Register. This is the first Tom Clark book I read. Amazing.