I finished David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King the other night (don’t worry—I know that there’s been a terrible shortage of coverage for this obscure book, so I’ll post a review pretty soon review here). The Pale King unfolds as a series of fragments, some short as one page, many the length of long short stories, and one novella length piece. Characters recur, but themes, images, and motifs hold these pieces together rather than any linear plot. The better pieces can stand on their own as short stories, yet are much richer when read with/against the rest of the novel. The Pale King remained unfinished at the time of Wallace’s death, but his notes on the manuscript (published at the end of the book) suggest that fragmentation was always his intentional method.

The fragmentary novel is nothing new, but its particular powers have gained resonance against the backdrop of a world where authority, information, and communication are increasingly decentralized, scattered, and, well, fragmented. Fragmentary novels might have roots in the picaresque (those one-damn-thing-after-the-next novels like Don Quixote, Candide, Huckleberry Finn, Invisible Man, Orlando, Blood Meridian . . .), but picaresque novels tend to have a shape, a trajectory, even if they seem to lack traditional plot arcs or characterization. What I’m talking about here are novels made of pieces, segments, or chapters that work fine on their own, and may even seem self-contained, but when synthesized help reveal the novel’s greater project. So, seven fragmentary novels that aren’t The Pale King—

Steps, Jerzy Kosinski

There’s force and vitality and horror in Steps, all compressed into lucid, compact little scenes. In terms of plot, some scenes connect to others, while most don’t. The book is unified by its themes of repression and alienation, its economy of rhythm, and, most especially, the consistent tone of its narrator. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it’s the same man relating all of these strange experiences because the way he relates them links them and enlarges them. At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Here’s David Foster Wallace: “Steps gets called a novel but it is really a collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that’s like nothing else anywhere ever. Only Kafka’s fragments get anywhere close to where Kosinski goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined.”

Speedboat, Renata Adler

Telegraphed in bristling, angular prose, Speedboat unwinds as a series of seemingly unrelated vignettes, japes, and jokes all filtered through the narrator’s ironic, faux-journalist sensibility. Adler’s novel eschews plot, conventional characters, and resolution—its contours are its center. Speedboat was published in the early 1970s, but it would seem ahead of its time even if it were published tomorrow. Adler captures the deep existential alienation of modern life, converting dread into verve and despair into marvel.

2666, Roberto Bolaño

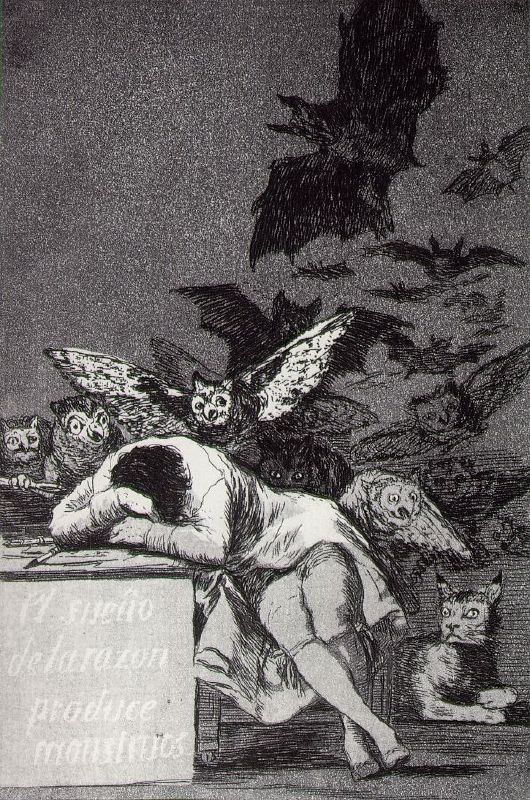

Bolaño’s opus bears considerable superficial comparison to Wallace’s The Pale King: both were published posthumously, both have endured a process of buzz and backlash, both are unfinished, and both are purposefully fragmented. 2666 comprises (at least five) parts, some connected explicitly, others tied loosely together, but all interwoven with themes of violence, darkness, art, and love. The book’s most notorious section, “The Part About the Crimes,” is itself a fragmented beast, a procession of murders and rapes, dead-end investigations, bizarre TV appearances, and other sinister doings. Prominent characters disappear into the violence of Santa Teresa never to return again; the great mystery of the book seems unsolved. But like Ariadne, Bolaño offers his readers a thread through the labyrinth, a layering of motifs, as words and images repeat throughout shifts in space and time.

Naked Lunch, William S. Burroughs

Naked Lunch’s cut-up origins are well-known and probably greatly exaggerated: the book is far more coherent than its reputation insists. Still, Burroughs’s infamous novel is all over the place (quite literally), moving through time and space and even to Interzone. Comic, rambling, lusty, and perverse, Naked Lunch’s satire is often overshadowed by its seedier, more sensational side. Burroughs claimed his novels were part of an antique literary pedigree: “I myself am in a very old tradition, namely, that of the picaresque novel. People complain that my novels have no plot. Well, a picaresque novel has no plot. It is simply a series of incidents.”

Vertigo, W. G. Sebald

Vertigo blurs the lines between fiction, history, autobiography, and biography. The book comprises four sections. The first section tells the story of the romantic novelist Stendhal (or, more to the point, a version of Stendhal); the second section details two trips Sebald made to Italy, one in 1980, and one in 1987; the third section describes a trip Kakfa took to Italy near the end of his life; the final section describes the narrator hiking from Austria to visit the village where he was born in Bavaria. Underwriting and uniting these separate episodes is the narrator’s attempt to find a common thread between past and present, to find a unity in a Europe fractured by time and war. There’s also a deep, throbbing melancholy mixed with beauty and wisdom here.

Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell

Mitchell constructs Cloud Atlas like a doubled matryoshka doll, nesting narratives inside narratives that work their way to an apocalyptic future; once Cloud Atlas hits its middle mark, it works outward to the past, back to its own edges. With the exception of the middle piece, a nod to Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, Mitchell fragments each piece of Cloud Atlas at a key turning point, an old literary trick really, but one that pays off. The tales likely hold up on their own, but their intertextual play is the real delight of the novel, as Mitchell showcases a variety of styles and genres and forms that reflect the content and era of each tale. At its core, Cloud Atlas explores Nietzschean themes of eternal recurrence and the will to power; its clever fragmented structure emphasizes the loops of history humanity finds itself caught in again and again, even as brave souls seek a new way of seeing, living, doing.

Go Down, Moses, William Faulkner

Faulkner always insisted that Go Down, Moses was a novel, although in its initial publication it was presented as a collection of short stories. And granted, any of the stories can be read on their own. “Was” is hilarious homosocial hijinks, but read against the sorrow and anger in “The Fire and the Hearth” and “Pantaloon in Black,” or the prolonged majesty of “The Bear,” Faulkner’s project becomes much clearer—he is taking on a century in the lives of the Mississippi McCaslins. Go Down, Moses is strange and sad and funny and truly an achievement, a book that works as a sort of time machine, an attempt to undo or recover the racial and familial (and in Faulkner, these are the same) divides of the past.

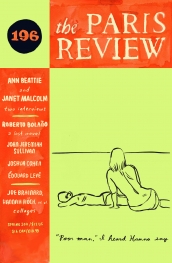

As a means of plot summary, here’s an excerpt from my review of the second part of Roberto Bolaño’s novel The Third Reich (serialized this year by The Paris Review and forthcoming in hardback from FSG (uh, the Bolaño’s book, not my review, of course))—

As a means of plot summary, here’s an excerpt from my review of the second part of Roberto Bolaño’s novel The Third Reich (serialized this year by The Paris Review and forthcoming in hardback from FSG (uh, the Bolaño’s book, not my review, of course))—

Two years ago, a typed manuscript for Roberto Bolaño’s unpublished novel The Third Reich The Third Reich was discovered. The Paris Review is serializing the novel, publishing it in full over four issues in a translation by Natasha Wimmer. I finished the first part of The Third Reich last night, reading the 63 pages in one engrossing session.

Two years ago, a typed manuscript for Roberto Bolaño’s unpublished novel The Third Reich The Third Reich was discovered. The Paris Review is serializing the novel, publishing it in full over four issues in a translation by Natasha Wimmer. I finished the first part of The Third Reich last night, reading the 63 pages in one engrossing session.