- Another riff on/citation from Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day.

-

In this episode, our heroes, Chums of Chance Chick Counterfly (chief science officer) and Darby Suckling (chief horndog) have found their way to an off-brand time machine, managed and (shoddily) maintained by Dr. Zoot (whose doctorate seems unlikely). Dr. Zoot sends the boys (ostensibly) to the future for a brief glimpse:

They seemed to be in the midst of some great storm in whose low illumination, presently, they could make out, in unremitting sweep across the field of vision, inclined at the same angle as the rain, if rain it was—some material descent, gray and wind-stressed—undoubted human identities, masses of souls, mounted, pillioned, on foot, ranging along together by the millions over the landscape accompanied by a comparably unmeasurable herd of horses. The multitude extended farther than they could see—a spectral cavalry, faces disquietingly wanting in detail, eyes little more than blurred sockets, the draping of garments constantly changing in an invisible flow which perhaps was only wind. Bright arrays of metallic points hung and drifted in three dimensions and perhaps more, like stars blown through by the shock waves of the Creation. Were those voices out there crying in pain? sometimes it almost sounded like singing. Sometimes a word or two, in a language almost recognizable, came through. Thus, galloping in unceasing flow ever ahead, denied any further control over their fate, the disconsolate company were borne terribly over the edge of the visible world. . . .

The chamber shook, as in a hurricane. Ozone permeated its interior like the musk attending some mating dance of automata, and the boys found themselves more and more disoriented. Soon even the cylindrical confines they had entered seemed to have fallen away, leaving them in a space unbounded in all directions. There became audible a continuous roar as of the ocean—but it was not the ocean—and soon cries as of beasts in open country, ferally purring stridencies passing overhead, sometimes too close for the lads to be altogether comfortable with—but they were not beasts. Everywhere rose the smell of excrement and dead tissue.

Each lad was looking intently through the darkness at the other, as if about to inquire when it would be considered proper to start screaming for help.

“If this is our host’s idea of the future—” Chick began, but he was abruptly checked by the emergence, from the ominous sweep of shadow surrounding them, of a long pole with a great metal hook on the end, of the sort commonly used to remove objectionable performers from the variety stage, which, being latched firmly about Chick’s neck, had in the next instant pulled him off into regions indecipherable. Before Darby had time to shout after, the Hook reappeared to perform a similar extraction on him, and quick as that, both youngsters found themselves back in the laboratory of Dr. Zoot. The fiendish “time machine,” still in one piece, quivered in its accustomed place, as if with merriment. (403-04)

- I think the most obvious interpretation here is that our Chums witness part of a battle of the Great War, which is where Against the Day seems to be heading.

- What I find most fascinating, though, is the way that Pynchon moves from the physical to the metaphysical in the series of images the Chums witness.

We get an image of “undoubted human identities, masses of souls, mounted, pillioned, on foot, ranging along together by the millions over the landscape accompanied by a comparably unmeasurable herd of horses” seems simultaneously concrete and metaphysical, specific but also hyperbolic.

The scene continues to tread this line—we witness “a spectral cavalry, faces disquietingly wanting in detail, eyes little more than blurred sockets, the draping of garments constantly changing in an invisible flow which perhaps was only wind.”

On one hand, our disoriented Chums (to whose perspective Pynchon limits us) perceive ghosts here (almost cartoonish ghosts, I might add, of the holes-cut-out-for-eyes variety); on the other hand, the “blurred sockets” suggest gas masks and the “constantly changing” garments could perhaps be the variety of uniforms (and armor) of the soldiers.

Continuing: “Bright arrays of metallic points hung and drifted in three dimensions and perhaps more” — Bullets? Bayonets? Missiles? The concrete image is then likened to “stars blown through by the shock waves of the Creation.” The physical shifts into the metaphysical again as Pynchon sends “the disconsolate company . . . terribly over the edge of the visible world.”

- Here, the Chums seem to experience the Great War as an intensely compressed allegorical sensation.

The second paragraph in the above citation moves the boys into “a space unbounded in all directions” where they perceive “a continuous roar as of the ocean—but it was not the ocean—and soon cries as of beasts in open country, ferally purring stridencies passing overhead, sometimes too close for the lads to be altogether comfortable with—but they were not beasts.”

The Chums have no language to describe what they hear; Pynchon has to mediate the similes available to them in negation. But we (and Darby and Chick, of course) know that this place is no bueno: “Everywhere rose the smell of excrement and dead tissue.”

- Where have they gone? Are they still in the midst of war—are the sounds planes, bombs? World War I? WWII, site of that other giant Pynchon novel? Hiroshima? Vietnam? The WTC on 9/11? Where? When?

- I take the second paragraph to be a brief homage to the penultimate chapter of H.G. Wells’s slim novel The Time Machine (frequently and directly invoked throughout this particular episode of AtD, btw). At the end of that novella, the time traveler, dispensing with Eloi and Morlock alike, takes his machine to the brink of time, to witness the end of the earth and our solar system: “A horror of this great darkness came on me. The cold, that smote to my marrow, and the pain I felt in breathing, overcame me. I shivered, and a deadly nausea seized me.” The Chums of Chance seem to witness a similar extinction.

-

Ah, but this is Pynchon, of course—so and how does the episode end? With a gag. In a vaudevillian twist, our players are removed from the stage via hook as the time machine, their audience, quivers “as if with merriment.”

Despite the zaniness of this exit, keep in mind that our heroes are hooked around their necks, lassoed by a noose of sorts—Pynchon saves them, but at the same time visually suggests their death, linking back to the image of mass extinction at the core of the passage.

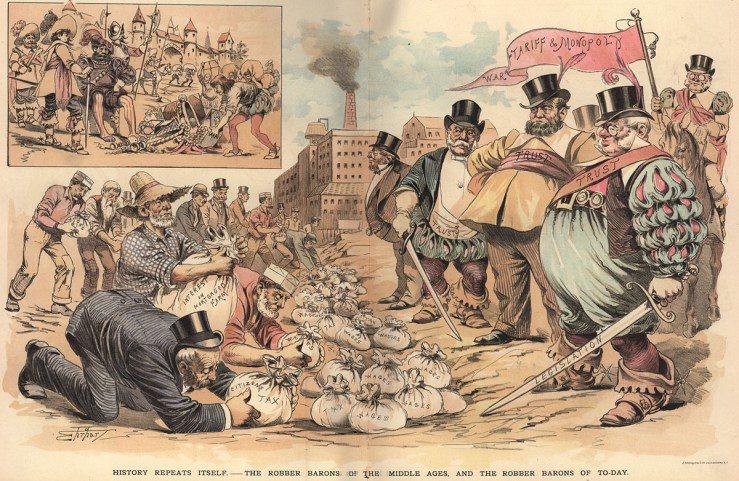

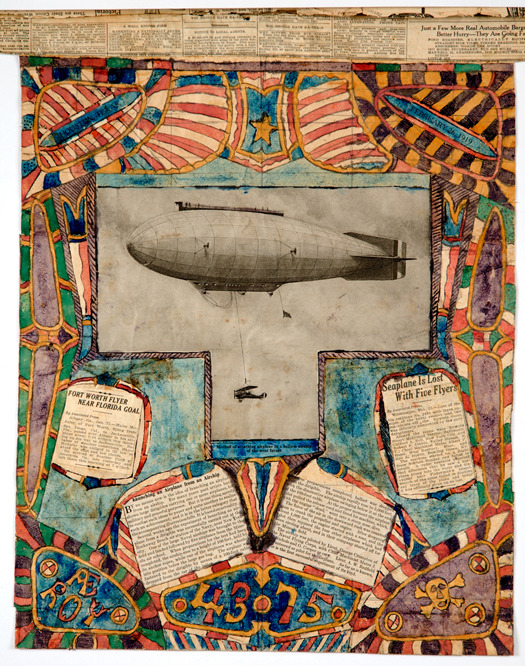

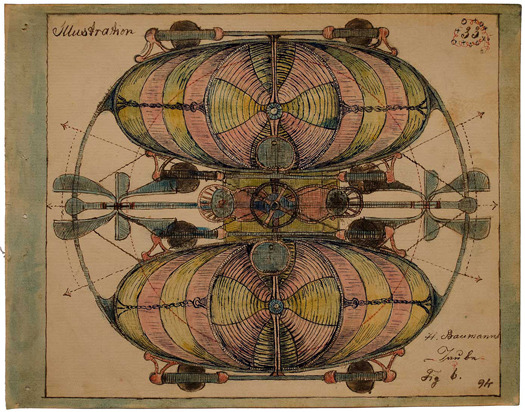

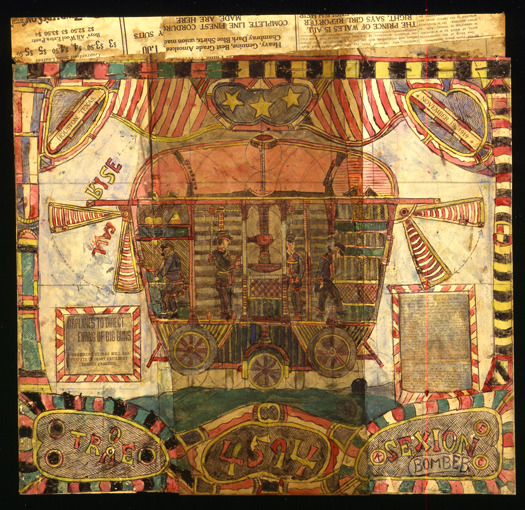

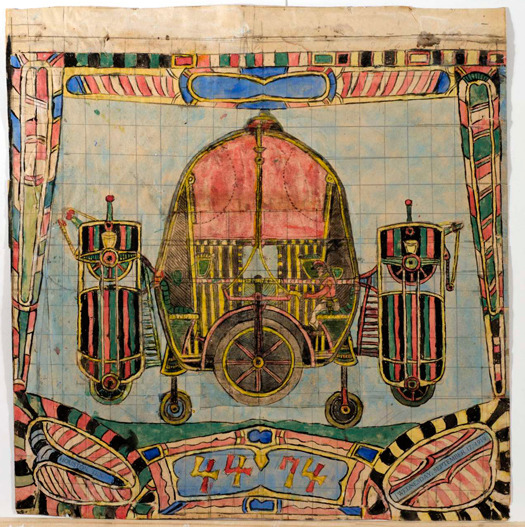

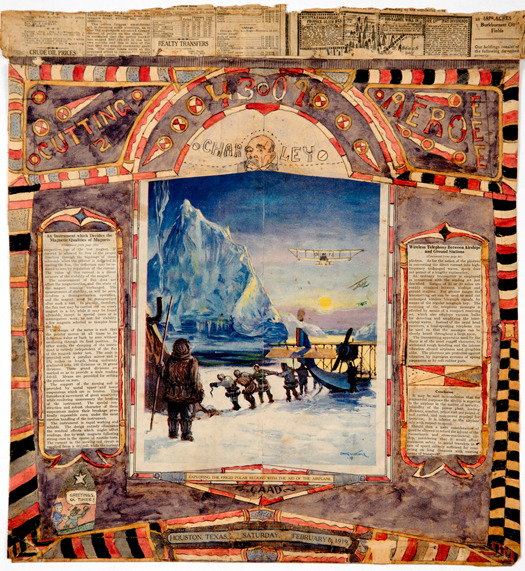

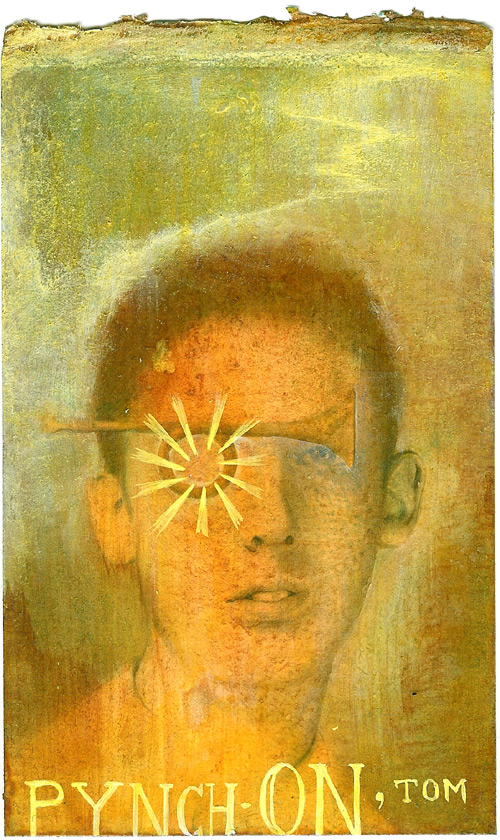

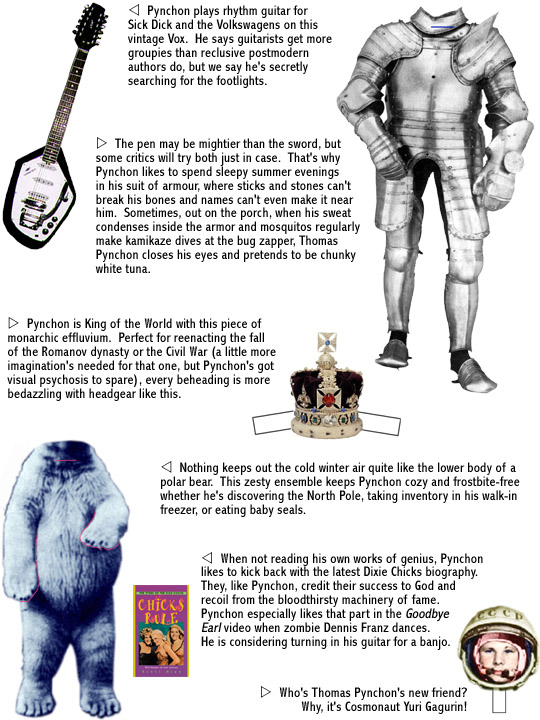

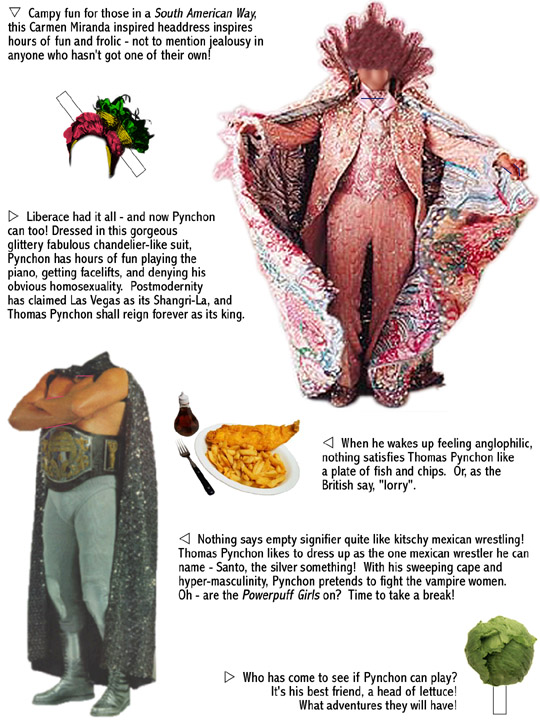

- The paintings in this riff are by the late Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński; like all of his work they are untitled.