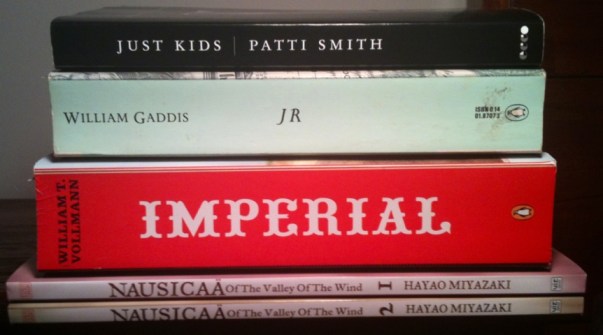

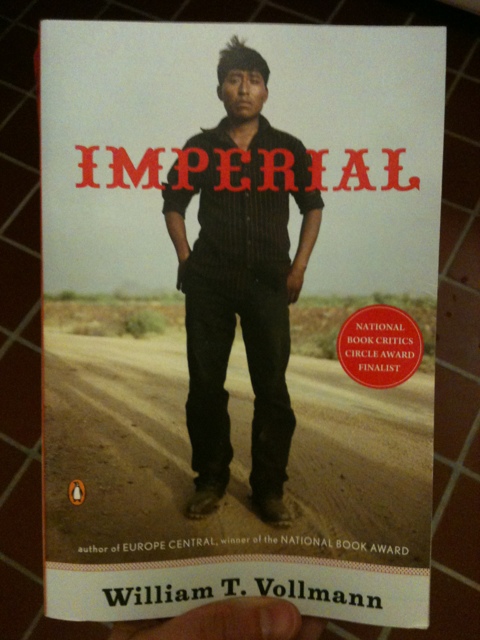

I had been reading William T. Vollmann’s enormous book Imperial. I bought the book in paperback and then put an illicit copy on my Kindle (this riff is not about the ethics of that move). It’s just easier to read that way, especially at night. At some point in Imperial, probably at some mention of coyotes or polleros—smugglers of humans—I felt a tug in the back of my brain pan, a tug that wanted to pull up Roberto Bolaño’s big big novel 2666—also on my Kindle (also an illicit copy, although I bought the book twice).

This is how I ended up rereading 2666 straight through. It was unplanned.

Like many readers, I aim to reread more than I actually end up rereading.

Truly excellent novels are always better in rereading: richer, fuller, more resonant. Sometimes we might find we’ve thoroughly misread them. (Imagine my horror rereading Lolita in my twenties to discover the vein of evil throbbing through it). Sometimes we find new tones that seemed impossible on the first run through. (I’ve read Blood Meridian at least once a year since the first time I read it, and it keeps getting funnier and funnier). Most of the time, rereading confirms the greatness of the novel, a greatness inhabiting the smallest details. (I’m looking at you Moby-Dick).

Even a riff should have a thesis, and here’s mine: 2666 has a reputation for being fragmentary and inconclusive—and in some ways, yes, of course it is—but a second full reading of 2666 reveals a book that is cohesive, densely allusive, and thematically precise.

Rereading is one way of stepping back to see the bigger picture that Bolaño twists together from smaller fragments. Rereading reveals the intertextual correspondences between the books of 2666 (the five books proper, the “Parts,” of course, but also the texts, invented or real, that those books house).

2666 is also a book about writing.

To wit: “The Part About Archimboldi,” the fifth and final book of 2666, the book that features Benno von Archimboldi, the writer at the heart of 2666—this final chapter sews together many of the book’s (apparently) loose threads.

Two problems with the point above:

A. Benno von Archimboldi (aka Hans Reiter) is not at the heart of 2666 but rather a shadowy trace slipping through the margins, a ghost-presence that’s always there, but not generative or muscular like a heart. (I’m not sure exactly what I mean by this).

B. “The Part About Archimboldi” most decidedly does not sew together all the loose threads: That’s the reader’s job (or task or pleasure or plight or burden).

And so then: “2666 is also a book about writing”): 2666 is also a book about reading: A book about reading as detective work.

Who are the heroes of 2666?

They are all detectives of some kind, literal or otherwise.

Literary critics. Journalists. Philosophers. Psychologists. Psychics and fortune tellers. Police detectives. Private detectives. An American sheriff. A rogue politician. Poets. Publishers. Parents. Searchers.

Archimboldi shows up in the first book of 2666, “The Part About the Critics”; the eponymous critics, literary detectives are searching for him.

How does Archimboldi show up?

Inside a story (the Frisian lady’s) inside a story (the Swabian’s) (inside the story of “Critics,” which is inside the story of 2666).

The Frisian lady asks:

“Does anyone know the answer to the riddle? Does anyone understand it? Is there by chance a man in this town who can tell me the solution, even if he has to whisper it in my ear?”

And Archimboldi answers. He’s a reader, a detective.

Swinging back to the previous point: 2666 is a book about writing, and it shares the postmodern feature of calling attention to its own style and construction, yet it never does this in an overtly clever or insufferable fashion: It’s far more sly.

What is the construction or shape of 2666?

A straightforward answer: Five books in an intertextual conversation that seem to loop back around, where the last book prefigures the first book in a strange circuit.

Some possible metaphorical answers:

A void (“Voids can’t be filled,” Archimboldi says).

A labyrinth (the word labyrinth appears 14 times in Wimmer’s translation of 2666).

A mirror (61 times).

An abyss (22 times)

An asylum (43 times; madhouse appears 5 times).

How does Bolaño slyly announce or criticize or puncture his style in 2666?

In Ignacio Echevarria’s “Note to the First Edition” of 2666, he tells us that:

Among Bolaño’s notes for 2666 there appears the single line: “The narrator of 2666 is Arturo Belano.” And elsewhere Bolaño adds, with the indication “for the end of 2666”: “And that’s it, friends. I’ve done it all, I’ve lived it all. If I had the strength, I’d cry. I bid you all goodbye, Arturo Belano.”

Belano is Bolaño’s alter ego, a trace who slips and sails and ducks through the Bolañoverse (he also shows up unnamed in 2666 with his partner Ulises Lima; they manage to father a bastard son, Lalo Cura).

So Belano who narrates 2666 (how?!) is Bolaño: Okay: So? Now?

I suggested earlier on Biblioklept that 2666 is a grand ventriloquist act, a forced possession, a psychic haunting. Bolaño channels Belano who channels detectives, journalists, poets, writers. Readers.

The channeling is metatextual or intertextual, a series of transpositions between the various narrators and protagonists and readers (detectives all).

The passage that I see most frequently cited from 2666 points to its intertextuality.

The passage is likely frequently cited because

A) Ignacio Echevarria cites it in his note at the beginning of 2666 and

B) it describes Bolaño’s project in 2666, both internally (the book as a strange beast, with intertextual readings within its five (plus) parts), and also externally (intertextually against the canon). Here is the passage (from “The Part About Amalfitano”):

One night, while the kid was scanning the shelves, Amalfitano asked him what books he liked and what book he was reading, just to make conversation. Without turning, the pharmacist answered that he liked books like The Metamorphosis, Bartleby, A Simple Heart, A Christmas Carol. And then he said that he was reading Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Leaving aside the fact that A Simple Heart and A Christmas Carol were stories, not books, there was something revelatory about the taste of this bookish young pharmacist, who in another life might have been Trakl or who in this life might still be writing poems as desperate as those of his distant Austrian counterpart, and who clearly and inarguably preferred minor works to major ones. He chose The Metamorphosis over The Trial, he chose Bartleby over Moby-Dick,he chose A Simple Heart over Bouvard and Pecuchet, and A Christmas Carol over A Tale of Two Cities or The Pickwick Papers. What a sad paradox, thought Amalfitano. Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze paths into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.

At the risk of belaboring or repeating the last point: Bolaño, ever the canon-maker, the list maker, situates 2666, his final work (he knows it’s his final work) along with “the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze paths into the unknown,” a book that struggles “against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.”

So some metatextual moments that, read intertextually, perhaps (perhaps!) work to outline that “unknown,” that “something” of 2666:

Near the end of “The Part About Crimes,” a culminating moment, where a female journalist (NB: a female journalist is the first murder victim in “Crimes”) reads the work of the poet/journalist Mercado:

Hernandez Mercado’s style wavered between sensationalism and flatness. The story was riddled with clichés, inaccuracies, sweeping statements, exaggerations, and flagrant lies. Sometimes Hernandez Mercado painted Haas as the scapegoat of a conspiracy of rich Sonorans and sometimes Haas appeared as an avenging angel or a detective locked in a cell but by no means defeated, gradually cornering his tormentors solely by dint of intelligence.

A description of the style of “The Part About the Crimes”: “The story was riddled with clichés, inaccuracies, sweeping statements, exaggerations, and flagrant lies.”

And, from “The Part About Archimboldi,” a moment where some critics read Ivanov’s novel Twilight and assess it:

Professor Stanislaw Strumilin read it. It struck him as hard to follow. The writer Aleksei Tolstoy read it. It struck him as chaotic. Andrei Zhdanov read it. He left it half finished. And Stalin read it. It struck him as suspect.

These are internal criticisms of 2666.

Another moment from Ansky’s journal that seems to describe “The Part About the Crimes,” 2666, and the Bolañoverse in general:

He mentions names Reiter has never heard before. Then, a few pages on, he mentions them again. As if he were afraid of forgetting them. Names, names, names. Those who made revolution and those who were devoured by that same revolution, though it wasn’t the same but another, not the dream but the nightmare that hides behind the eyelids of the dream.

While I’m using Ansky’s journal as a pseudo key for the intertextual labyrinth of 2666, let me grab this nugget:

Only in chaos are we conceivable.

(I added the note “thesis” in the electronic margin).

Or another description of the novel, couched in a description of history:

. . . history, which is a simple whore, has no decisive moments but is a proliferation of instants, brief interludes that vie with one another in monstrousness.

Another description of 2666 can be found in Bubis’s description of Archimboldi’s second novel:

Lüdicke had yet to come off the presses when Mr. Bubis received the manuscript of The Endless Rose, which he read in two nights, after which, deeply shaken, he woke his wife and told her they would have to publish this new book by Archimboldi.

“Is it good?” asked the baroness, half asleep and not bothering to sit up.

“It’s better than good,” said Bubis, pacing the room.

Then he began to talk, still pacing, about Europe, Greek mythology, and something vaguely like a police investigation, but the baroness fell back asleep and didn’t hear him.

The names of the novels here also suggest something about the structure of 2666: The Endless Rose suggests an eternal loop, as does Lüdicke, which etymologically suggests ludic, recursively playful . . . (Again, I’m just riffing here).

Another description of Archimboldi’s writing, which is of course a description of Bolaño’s 2666:

The style was strange. The writing was clear and sometimes even transparent, but the way the stories followed one after another didn’t lead anywhere: all that was left were the children, their parents, the animals, some neighbors, and in the end, all that was really left was nature, a nature that dissolved little by little in a boiling cauldron until it vanished completely.

Archimboldi’s name is some sort of secret key to the novel. He invents the name, of course, seemingly on the spot. (Invents is not the right word—rather, he synthesizes the name, cobbles it together from his readings. The name is intertextual).

The last name he appropriates from the painter Arcimboldo, whose paintings are instructive in understanding the structure of 2666, a narrative that comprises hundreds of internal discrete narratives that define the shape of the larger picture. The first name?

“They called me Benno after Benito Juarez,” said Archimboldi, “I suppose you know who Benito Juarez was.”

The dark heart of 2666, site of “Crimes,” is Santa Teresa, a transparent stand-in for Ciudad Juarez.

(Florita Almada, psychic medium and honest detective of “Crimes” channels Benito Juarez, the shepherd boy who became the president of Mexico; I’m tempted to quote here at some length but resist).

Re: Above: I foolishly suggested that Archimboldi’s name is some sort of secret key. I don’t think there is a secret key. Just reading. Rereading.

I seem to be focusing a lot on “The Part About Archimboldi” in this riff. I riffed about the first three books here, and “The Part About Crimes” here.

But, still dwelling on “Archimboldi,” there’s a moment in it where an old alpine hermit confesses to murdering his wife by pushing her into a ravine. In some way his confession seems to answer all the puzzles of “Crimes,” all the unresolved abysses, all the falls (literal and metaphorical). How can I justify this claim? How does a man confessing to a murder in a remote German border town in the 1950s answer the murders in Mexico in the 1990s? Or any of the other murders in the book? I suppose it’s a thematic echo, not a solution. Sweating late at night, reading past midnight, the moment struck me as larded with significance. I’m losing whatever thread I had . . .

So to end—how to end? Perhaps I’ll raid my first review of 2666, from January, 2009—surely I must have remarked on the end of the book, or on its apparent inconclusiveness—

—and so I did. And I don’t know if I can do better than this:

Readers enthralled by the murder-mystery aspects of the novel, particularly the throbbing detective beat of “The Part About The Crimes,” may find themselves disappointed by the seemingly ambiguous or inconclusive or open-ended ending(s) of 2666. While the final moments of “The Part About Archimboldi” dramatically tie directly into the “Crimes” and “Fate” sections, they hardly provide the types of conclusive, definitive answers that many readers demand. However, I think that the ending is perfect, and that far from providing no answers, the novel is larded with answers, bursting at the seams with answers, too many answers to swallow and digest in one sitting. Like a promising, strangely familiar turn in the labyrinth, the last page of the book invites the reader back to another, previously visited corridor, a hidden passage perhaps, a thread now charged with new importance . . . 2666 is a book that demands multiple readings.

It was a good suggestion three years ago and I’ll take it up again.

It’s sort of like those kids who had pet monkeys when you were in elementary school, always someone’s cousin, or their neighbor’s friend from another school; sometimes the story was accompanied by a thumbprint-smudged Polaroid of the creature, clutching lovingly to some human torso. But did you ever actually see it? No never. Not once. And anyone who says they did is part of the conspiracy. Sure, maybe somewhere in Mexico someone has a monkey for a pet, but not here, no way, and certainly not your cousin. And look, I agree that it’s a weird thing to lie about, but that’s part of what makes good liars good, it’s some sort of weird emotional long-con that you are complicit in by listening to them.

It’s sort of like those kids who had pet monkeys when you were in elementary school, always someone’s cousin, or their neighbor’s friend from another school; sometimes the story was accompanied by a thumbprint-smudged Polaroid of the creature, clutching lovingly to some human torso. But did you ever actually see it? No never. Not once. And anyone who says they did is part of the conspiracy. Sure, maybe somewhere in Mexico someone has a monkey for a pet, but not here, no way, and certainly not your cousin. And look, I agree that it’s a weird thing to lie about, but that’s part of what makes good liars good, it’s some sort of weird emotional long-con that you are complicit in by listening to them. So, I’m thinking this thing goes deep, deeper than any of us ever imagined. Obviously Dave Eggers is involved somehow, either as the mastermind behind the whole thing, or just another pawn like the rest of us. I emailed Mr. Heartbreaking Jerk himself, asking if even he of all people can claim to have actually read all of Rising Up and Rising Down, and in return I received an auto-reply, something about the volume of emails he receives blah blah blah—the point is I think I scared him, and now I know I’m on the right trail . . .

So, I’m thinking this thing goes deep, deeper than any of us ever imagined. Obviously Dave Eggers is involved somehow, either as the mastermind behind the whole thing, or just another pawn like the rest of us. I emailed Mr. Heartbreaking Jerk himself, asking if even he of all people can claim to have actually read all of Rising Up and Rising Down, and in return I received an auto-reply, something about the volume of emails he receives blah blah blah—the point is I think I scared him, and now I know I’m on the right trail . . .