I called the Dove World Outreach Center this afternoon to find out some details about their upcoming book burning.

The woman who answered the phone seemed tense but polite, wanting to know what organization I was with. I told her that I just wanted to find out a few simple facts about the book burning. First, I wanted to confirm that the church still plans to burn copies of the Qur’an on September 11th, 2010. In a New York Times article from August 25th, the church’s pastor Terry Jones avowed that the book burning would still take place, despite the Gainesville Fire Department denying them a permit. The woman I spoke to confirmed that the book burning will still take place.

I wanted to know where the Qur’ans that were to be burned were coming from. I asked if they belonged to the church. The woman was genuinely confused at this. “No, we’re a church. We don’t have any Qur’ans.” I clarified my question. “They’ve been donated to the church,” she replied, and wouldn’t elaborate. The conversation was getting a bit tense.

I asked her if people should bring their own Qur’ans to the book burning to burn. This again seemed confusing. “No, the event is closed to the public,” she explained. The police advised the church, for “security reasons” to restrict the book burning to only church members. I asked if this means that I couldn’t attend the burning if I was not a church member. She explained that I would be able to see the burning from the side of the road from behind a fence, but that nonmembers could not attend.

I then asked how the books would be burned. Again, a pause; perhaps confusion. I felt like I was about to get hung-up on. “Just wood, I think, is my understanding,” she said. “No gas?” I asked. “I’m not sure,” she replied. “So, you’ll burn them like, bonfire-style? A pyre? No pit?” A longer pause. “I’m not really sure,” she finally said. “And people can witness that from the road, but not up close?” I asked. “Yes.”

So I’ll admit it: I’m a lousy reporter. I didn’t get that much info. I set out to find out some very basic, concrete information about the logistics of a book burning in 2010. Where do you get the materials? How do you burn them? I suppose my efforts and my aim to be objective obscured, at least for a moment, the fact that there are few things as ignorant and idiotic as a book burning. Any group of yokels could undertake such an operation. It really doesn’t need much practical forethought. You just need some wood (and possibly gasoline). And a Facebook page. And a willingness to engage in a special kind of evil. No wonder my questions were met with terse confusion.

I didn’t aim to compete with the NYT article, which does a pretty good job of painting the scene in Gainesville, FL, interviewing Jones, along with local Muslims, people who live near the church, and local Christian leaders. There seems to be unanimous disgust with the book burning. I lived in Gainesville for four years while I attended the University of Florida. I still live very close to it. Jones and his organization do not represent the values of the people who live in Gainesville or the people of Florida; nor do they represent American values.

The nineteenth-century German poet Heinrich Heine famously said that, “Where they burn books, they will ultimately also burn people” — and then they did, in twentieth-century Germany. I toyed with the idea of titling this post something like “Ignorant Yokels Plan Book Burning” but that seemed too dismissive, too snarky (even if perhaps true). (Also, Michael Moore has already used the poetic and appropriate title “Fahrenheit 9/11”). I’m not arguing for Jones and his ilk to be mocked (although thinking people will do so). And I wouldn’t demand that outside forces stop the church from performing this evil ritual on their own private property. Rather, I believe we must point to Dove World Outreach Center’s book burning as an example of the worst of human thinking and action, and agree that it exists outside the bounds of our culture and our society. We must recognize that book burning is inherently anti-human.

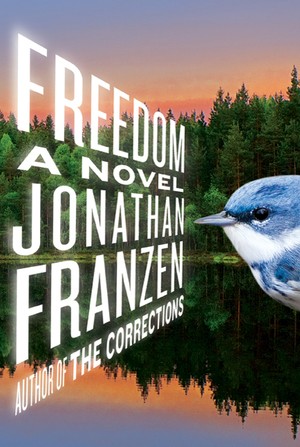

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

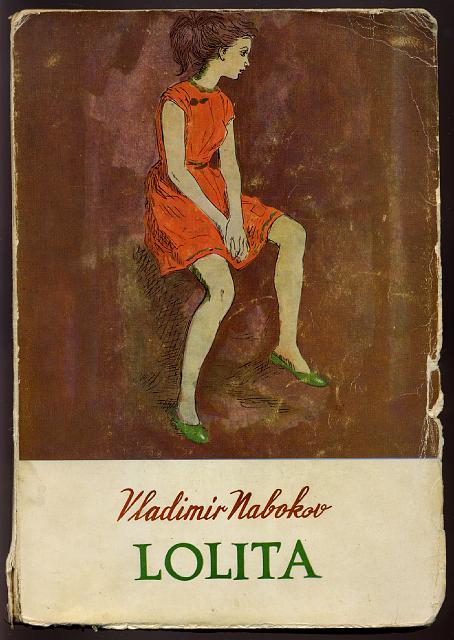

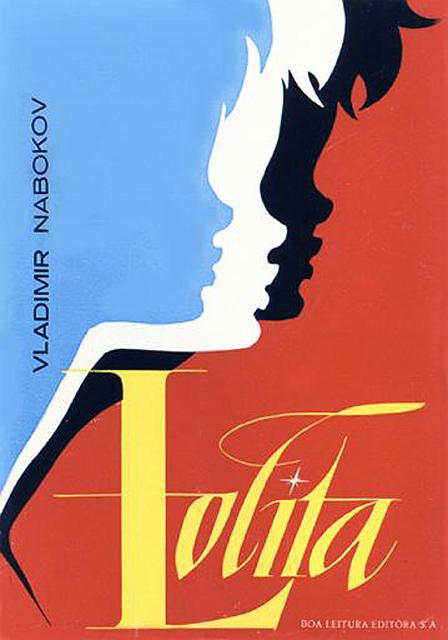

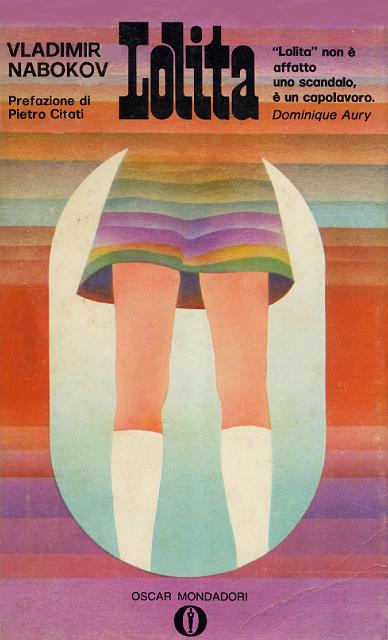

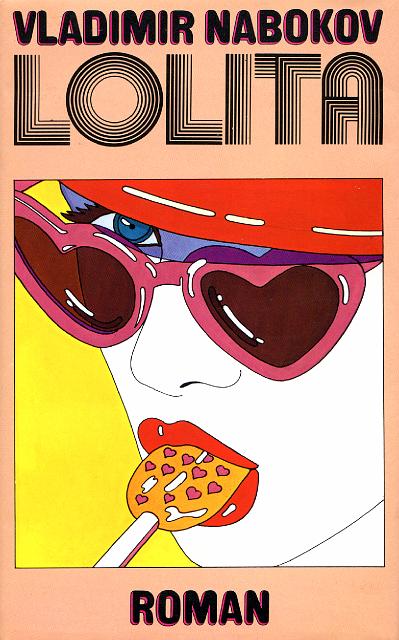

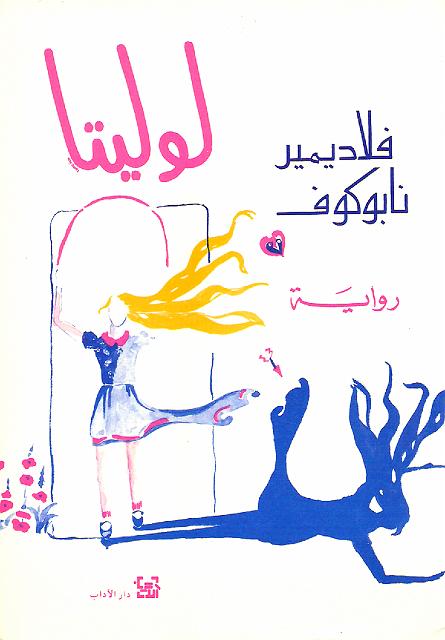

1962, Brazil.

1962, Brazil.

Nearly a year after earning

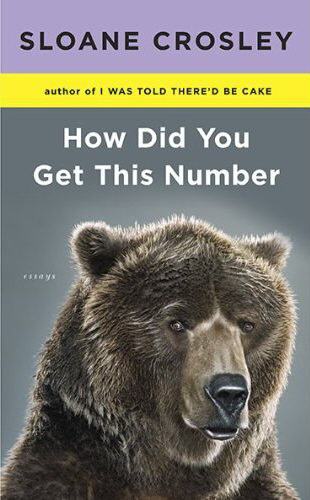

Nearly a year after earning  Sloane Crosley’s new collection of memory essays, How Did You Get This Number, finds the witty, observational young lass being witty and observational in and out of New York City–but mostly in. There are trips to Portugal and Paris, and a weird wedding in Alaska. There’s a remembrance of all the childhood pets that didn’t make it. There’s a story about buying furniture of questionable origin off the back of a truck. At times Crosley’s archness can be grating, as dry observations pile one upon the other, but her gift for exacting, sharp detail and her willingness to let her guard down at just the right moment in most of the selections make for a funny and compelling read. I’m still not sure why there’s no question mark in the title, though. How Did You Get This Number is new in hardback from Riverhead Books.

Sloane Crosley’s new collection of memory essays, How Did You Get This Number, finds the witty, observational young lass being witty and observational in and out of New York City–but mostly in. There are trips to Portugal and Paris, and a weird wedding in Alaska. There’s a remembrance of all the childhood pets that didn’t make it. There’s a story about buying furniture of questionable origin off the back of a truck. At times Crosley’s archness can be grating, as dry observations pile one upon the other, but her gift for exacting, sharp detail and her willingness to let her guard down at just the right moment in most of the selections make for a funny and compelling read. I’m still not sure why there’s no question mark in the title, though. How Did You Get This Number is new in hardback from Riverhead Books. I just got my advance review copy of James Ellroy’s forthcoming memoir The Hilliker Curse, so I haven’t had time to read much of it, but the story so far is morbidly fascinating (like, you know, an Ellroy novel. But this is real. Because it’s a memoir). In 1958, James’s mother Jean Hilliker had divorced her husband and begun binge drinking. When she hit him one night, the ten year old boy wished that she would die. Three months later she was found murdered on the side of the road–the case remains unsolved. The memoir details Ellroy’s extreme guilt; his sincere belief that he had literally cursed his mother pollutes his life, particularly in his complex relationships with women. Full review forthcoming. The Hilliker Curse is available September 7th, 2010 from Knopf.

I just got my advance review copy of James Ellroy’s forthcoming memoir The Hilliker Curse, so I haven’t had time to read much of it, but the story so far is morbidly fascinating (like, you know, an Ellroy novel. But this is real. Because it’s a memoir). In 1958, James’s mother Jean Hilliker had divorced her husband and begun binge drinking. When she hit him one night, the ten year old boy wished that she would die. Three months later she was found murdered on the side of the road–the case remains unsolved. The memoir details Ellroy’s extreme guilt; his sincere belief that he had literally cursed his mother pollutes his life, particularly in his complex relationships with women. Full review forthcoming. The Hilliker Curse is available September 7th, 2010 from Knopf.