Newsweek has published a series of scenes David Foster Wallace cut from his manuscript of Infinite Jest. Fascinating for fans. (Thanks to @mattbucher for the tip). Here’s “Hal’s Essay on Ducks”–

Newsweek has published a series of scenes David Foster Wallace cut from his manuscript of Infinite Jest. Fascinating for fans. (Thanks to @mattbucher for the tip). Here’s “Hal’s Essay on Ducks”–

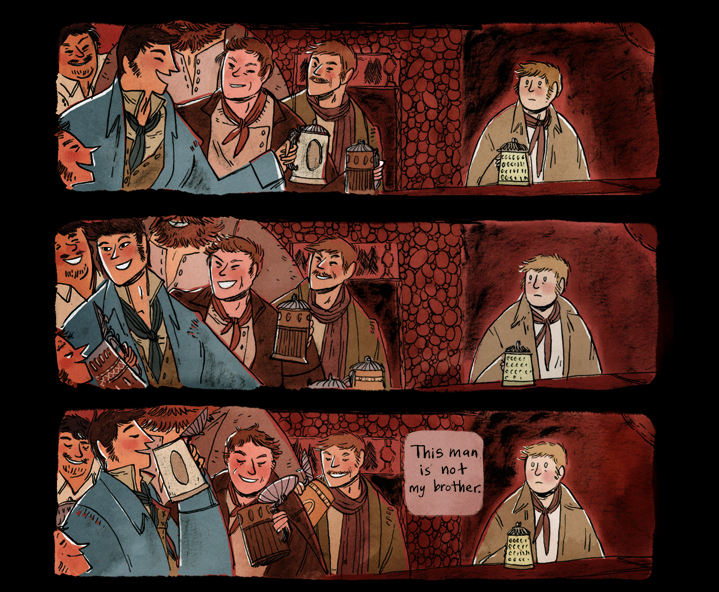

Cartoonist Kate Beaton riffs on Macbeth. From her site Hark! A Vagrant.

The AV Club’s Sam Adams interviews Charles Burns about Tintin, Burroughs, why he’s not involved in making the Black Hole movie, 1977, why he had to change how he colored his art, and his new book, X’ed Out. There’s also this nugget (we’d been wondering)–

The AV Club’s Sam Adams interviews Charles Burns about Tintin, Burroughs, why he’s not involved in making the Black Hole movie, 1977, why he had to change how he colored his art, and his new book, X’ed Out. There’s also this nugget (we’d been wondering)–

AVC: Is the completed three-volume work going to be called X’ed Out?

CB: They’re all going to be different stories. So for the next one, it says “Next: The Hive.” So the next book is called The Hive.

AVC: Is there a name for the trilogy?

CB: No, not in my mind.

[Editorial note–We originally ran this post in the summer of 2009 when Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was in theaters. We run it again now to celebrate the premiere of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part I (we also are running it again ’cause we’re lazy)].

First thing’s first: if you’re looking for Harry Potter slash fiction, you’ll have to check out our original Harry Potter Sex Romp post for links, you dirty dawg (you’re weird but you’re welcome). Just like that post a few years ago, this post’s title is really kinda sorta mostly irrelevant to what this post is about. What is it about? I want to take a look at some of the homoerotic tension in the new Harry Potter movie, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. If you want to find a proper review of the film, with plot summary and insight, shop around. That’s not gonna happen here.

Also, there will be SPOILERS, okay? Fair warning.

Okay. So, I saw the new film last night (henceforth HP6). And it was pretty good or whatever. But I noticed a subtext that cracked me up quite a bit, an underlying motif that might be lost on most summer blockbuster audiences. I’m talking about the implicit love between men and boys in this film.

At the beginning of the film, in an apparently insignificant scene, young Harry makes a date with an attractive young girl. However, old man Dumbledore shows up and dashes any hopes for a late sumer romance. Instead of meeting up with this lithe young thing, Harry has to grip hard to Dumbledore’s stiff arm to be apparated away to meet Horace Slughorn, an old potions master. Dumbledore uses Harry as fresh young bait for Slughorn, who has something the old wizard needs–a key memory about the development of Tom Riddle–Voldemort–a former protégé of Horace’s (lots of mentors and mentees here). Much of the narrative’s conflict revolves around the task Dumbledore has given Harry; it’s almost as if Dumbledore is pimping out the young wizard. These multiple man-boy relationships are doubled darkly in the failing bond between Snape and emo Draco.

In contrast, heterosexual relationships between the teens are treated with a lightness and even frivolity that codes such romances as ephemeral, or perhaps even inessential. Although the film solidifies the groundwork for the long-term relationships between the series’ principals (Harry-Ginny/Ron-Hermione), the real love story here is between older men and their young apprentices. HP6 depicts teen romance as silly without coloring any of its fragility with pathos. What the film really argues for is a sort of Greek or Platonic ideal of love; that love exists as a conduit for wisdom, passed from an older, experienced man to a younger boy in exchange for some of that youth’s beauty and vitality. Although moments of teenage adventure punctuate the film, the real scope of heroic encounters are shared between older men and their attendant lads (particularly Dumbledore and Harry, although even Snape, through the annotations of his old textbook, manages to plant part of himself into Harry).

The film reaches its climax with a lot of phallic wand waving and a bit of indecision over who gets to shoot off at whom. The climactic scene encodes the strange aggressions and series of shifting allegiances between the male wizards present. Dumbledore becomes the tragic figure; his death allows for Harry’s maturation, enacting a definitive arc in Harry’s Oedipal complex, where Dumbledore is both father figure and secret sex object. The weight of this tragedy initiates Harry into the adult world and adult responsibilities.

So why bother to write about this? No reason really, and I’m sure plenty of readers will find my analysis insupportable, silly, offensive, or just plain wrong. That’s fine. I guess I mostly find it remarkable that this motif should prevail so heavily in a summer blockbuster. There was also a whole drug motif going on–so many of the film’s plot development hinge on the ingestion of mind-altering substances–so maybe I just like the idea that the film is kinda sorta subversive.

The Ozark folktale “Have You Ever Been Diddled?” from Vance Randolph’s indispensable collection, Pissing in the Snow & Other Ozark Folktales–

[Told by J.L. Russell, Harrison, Ark., April, 1950. He heard this one near Berryville, Ark., in the 1890s.]

One time there was a town girl and a country girl got to talking about the boys they had went with. The town girl told what kind of car her boyfriends used to drive, and how much money their folks has got. But the country girl didn’t take no interest in things like that, and she says the fellows are always trying to get into her pants.

So finally the town girl says, “Have you ever been diddled?” The country girl giggled, and she says yes, a little bit. “How much?” says the town girl. “Oh, about like that,” says the country girl, and she held up her finger to show an inch, or maybe an inch and a half.

The town girl just laughed, and pretty soon the country girl says, “Have you ever been diddled?” The town girl says of course she has, lots of times. “How much?” says the country girl. “Oh, about like that,” says the town girl, and she marked off about eight inches, or maybe nine.

The country girl just sat there goggle-eyed, and she drawed a deep breath. “My God,” says the country girl, “that ain’t diddling! Why, you’ve been fucked!“

UPDATE: The contest is closed–and in record time.

Want to win a copy of The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis? Of course you do. The book makes a hefty stocking stuffer, so you could even give it away if you wanted to, but we suggest you do the selfish thing and hold on to it. It’s excellent.

Picador has kindly agreed to give a copy to one lucky Biblioklept reader (you must have a U.S. address, though). Win this handsome Davis volume by being the first to correctly answer all three questions of our quiz. Post your answers in the comments section.

1. Lydia Davis was married to another famous writer back in the 1970s. Name that writer and his new novel.

2. One of Davis’s short story collections is titled Samuel Johnson Is Indignant. Why is Dr. Johnson indignant? (Hint: Read our review).

3. In a 2008 interview with The Believer, Davis commented that she tried to translate/update a famous 18th century Irish novelist’s work. Who was the writer?

Vodpod videos no longer available.

“Hostess” by Amy Hempel–

She swallowed Gore Vidal. Then she swallowed Donald Trump. She took a blue capsule and a gold spansule–a B-complex and an E–and put them on the tablecloth a few inches apart. She pointed the one at the other. “Martha Stewart,” she said, “meet Oprah Winfrey.” She swallowed them both without water.

(From Micro Fiction, edited by Jerome Stern).

The Ozark folktale “Pissing in the Snow,” as told to Vance Randolph by Frank Hembree in 1945. Hembree first heard the tale in the 1890s. From Randolph’s indispensable collection, Pissing in the Snow & Other Ozark Folktales—

One time there was two farmers that lived out on the road to Carico. They was always good friends, and Bill’s oldest boy had been a-sparking one of Sam’s daughters. Everything was going fine till the morning they met down by the creek, and Sam was pretty goddam mad. “Bill,” says he, “from now on I don’t want that boy of yours to set foot on my place.”

“Why, what’s he done?” asked the boy’s daddy.

“He’s pissed in the snow, that’s what he done, right in front of my house!”

“But surely there ain’t no great harm in that,” Bill says.

“No harm!” hollered Sam. “Hell’s fire, he pissed so it spelled Lucy’s name, right there in the snow!”

“The boy shouldn’t have done that,” says Bill. “But I don’t see nothing so terrible bad about it.”

“Well, by God, I do!” yelled Sam. “There was two sets of tracks! And besides, don’t you think I know my own daughter’s handwriting?”

Henry Miller, in a 1962 Paris Review interview, speaks about surrealism, dada, and his love for Lewis Carroll—

INTERVIEWER

In “An Open Letter to Surrealists Everywhere” you say, “I was writing surrealistically in America before I ever heard the word.” Now, what do you mean by surrealism?

MILLER

When I was living in Paris, we had an expression, a very American one, which in a way explains it better than anything else. We used to say, “Let’s take the lead.” That meant going off the deep end, diving into the unconscious, just obeying your instincts, following your impulses, of the heart, or the guts, or whatever you want to call it. But that’s my way of putting it, that isn’t really surrealist doctrine; that wouldn’t hold water, I’m afraid, with an André Breton. However, the French standpoint, the doctrinaire standpoint, didn’t mean too much to me. All I cared about was that I found in it another means of expression, an added one, a heightened one, but one to be used very judiciously. When the well-known surrealists employed this technique, they did it too deliberately, it seemed to me. It became unintelligible, it served no purpose. Once one loses all intelligibility, one is lost, I think.

INTERVIEWER

Is surrealism what you mean by the phrase “into the night life”?

MILLER

Yes, there it was primarily the dream. The surrealists make use of the dream, and of course that’s always a marvelous fecund aspect of experience. Consciously or unconsciously, all writers employ the dream, even when they’re not surrealists. The waking mind, you see, is the least serviceable in the arts. In the process of writing one is struggling to bring out what is unknown to himself. To put down merely what one is conscious of means nothing, really, gets one nowhere. Anybody can do that with a little practice, anybody can become that kind of writer.

INTERVIEWER

You have called Lewis Carroll a surrealist, and his name suggests the kind of jabberwocky which you use occasionally . . .

MILLER

Yes, yes, of course Lewis Carroll is a writer I love. I would give my right arm to have written his books, or to be able to come anywhere near doing what he did. When I finish my project, if I continue writing, I would love to write sheer nonsense.

INTERVIEWER

What about Dadaism? Did you ever get into that?

MILLER

Yes, Dadaism was even more important to me than surrealism. The Dadaist movement was something truly revolutionary. It was a deliberate conscious effort to turn the tables upside down, to show the absolute insanity of our present-day life, the worthlessness of all our values. There were wonderful men in the Dadaist movement, and they all had a sense of humor. It was something to make you laugh, but also to make you think.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

Via Ubuweb—

Dinner With Henry is a rare, 30-minute documentary about Henry Miller. It is exactly what the title implies: footage of Henry having dinner. With him at the table is the film crew, and actress/model Brenda Venus, to whom Henry was enamoured in the final years of life. Henry – at age 87 – spends the majority of his time speaking on a number of subjects, the most persistent of which is Blaise Cendrars. Occasionally, he complains about the food. That is all. It may not be of much interest to a general audience, but is a curious “slice of life” for any Miller fan who likes to imagine being at the table with him.

Jonathan Safran Foer’s new book, Tree of Codes, is a cut-up — or cut-out, rather — of Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles. More here.

I’ve heard that you said, when a scene you had revised

Still didn’t suit a man you used to know,

“But I am not Kafka!” What artist hasn’t sized

Himself in the dwindling lacquer row

Of chinese dolls that, with no loss of face,

Can be out back inside one another now

And only a fool quarrel about his place.

There are such ranks; and yet I quarrel with

Those who have put a price on mere despair,

Ranking a man as he can fetch up death

And senselessness, and finding you famous so.

You called your foe by name: a naive faith.

It is a naive disillusion, everywhere

Fudging the good and bad, we must call foe.

The truth is hidden as cunningly from one

Time as another; what they change is the decoys,

And it takes a wily man to use the gun.

I think you would not be fooled by our bully-boys

Who say, “As Brecht said, I live in an age of blood.”

You might stop with an oath their shrill, untimely noise:

Evil is nothing until it touches good.

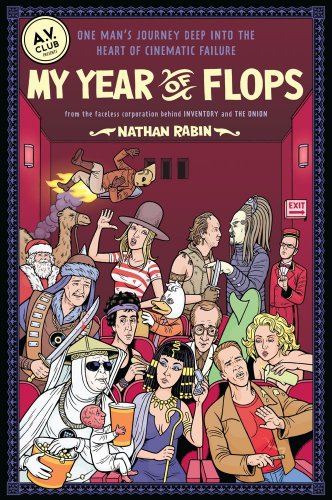

Let me admit biases up front: for the past few years, I’ve looked forward every Wednesday to Nathan Rabin’s regular column at the AV Club,“My Year of Flops,” where he reviews–and reappraises–some of the worst-received films of all time. I’m also a fan of Rabin’s other columns, “THEN! That’s What They Called Music!” and “Nashville or Bust,” as well as the general tone of the AV Club, which he no doubt helps set as its head writer. I also thought Rabin’s memoir The Big Rewind was pretty good. So, I’m probably not the most objective person to review Rabin’s new book My Year of Flops, which comprises 35 of Rabin’s past columns, 15 new entries, and interview snippets with some of the actors who had the (mis)fortune to turn up in these flops. I’ll do my best to assess how well these columns–most of which were written for the internet–hold up as a book.

So, what, exactly, constitutes a flop? There are the biggies here, of course, infamous studio-busting career-killers like Heaven’s Gate, Battlefield Earth, and Ishtar; the batshit crazy weirdfests that were destined to become cult classics, like Southland Tales, Howard the Duck, and The Apple; the disposable movies made to be forgotten, like Bratz: The Movie; there are forgotten and overlooked oddballs, like Robert Altman’s teen sex comedy, O.C. and Stiggs, and Gospel Road, where Johnny Cash tells the life story of Jesus. All of these films share disappointing (or non-existent) box office results as well as general critical disapproval (or at least bewilderment). As part of his revisionist project, Rabin ends each entry by declaring the re-appraised film a “Secret Success,” a “Fiasco,” or a “Failure.” Tellingly, most of the time Rabin finds his subject to be a “Fiasco.” He’s willing to take each film on its own terms; he’s also incredibly open to viewing each film in a way that transcends the trappings of its marketing to an intended audience.

Take, for example Tough Guys Don’t Dance, a film macho novelist Norman Mailer thought it would be a totally sound idea to not only write but direct. Rabin’s initial analysis derides the film for its cardboard characters, debased gimmickry, and embarrassing dialog. By the end of his reassessment, however, Rabin has given the would-be thriller a new life as “a darkly comic, horror-tinged melodrama about the emptiness of excess and the soul-crushing costs of pursuing endless pleasure.” His review rests not on a personal ironic vision, but rather on a willingness to see Mailer’s own ironic vision at work behind (and in front of) the camera.

In the same way, Rabin is able to put aside–even while acknowledging–the dreadful reputations surrounding films like Ishtar and Heaven’s Gate. Even though the latter film essentially destroyed both its studio and the maverick filmmaking style of the 1970s, Rabin finds in it more than a slight redemption–he finds a flawed masterpiece, a gorgeous treatise on Manifest Destiny that doesn’t deserve its reputation. Similarly, Rabin would have us believe that Istar actually is funny. Both of these entries are remarkable not just in their clear revisionist goal, but also for how instructive they are. In both write-ups, Rabin reveals much of how movies are made, and how movies are made flops–the ways that infighting, firings, and studio expectations can damn a film before it even premieres.

While My Year of Flops is instructive in its criticism, it’s also very entertaining. Rabin has a keen sense of satire, and if he occasionally tips into snark, it’s always earned (and if you have a problem with a writer being snarky at the expense of Battlefield Earth, well, you’re probably a prig anyway). A great illustration of how Rabin combines his sense of humor with his instructive criticism in his coinage of the term “Manic Pixie Dream Girl”–

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors, who use them to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl serves as a means to an end, not a flesh-and-blood human being. Once life lessons have been imparted, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl might as well disappear in a poof! for her life’s work is done.

Cameron Crowe is particularly guilty of employing the MPDG trope, but you can find her pretty much everywhere you look–at least in the domain of rom-coms. Rabin proposes the term in his first entry in the series (also the first entry in the book) a review of Crowe’s much maligned Elizabethtown. Rabin finds it to be a Fiasco. In a move that sums up both Rabin’s program and his generous spirit, Rabin concludes My Year of Flops by re-reassessing Elizabethtown–he now dubs it a Secret Success. While I don’t subscribe to the idea that a critic should-be a starry-eyed optimist who finds the best of all possible worlds in each work, I do think that it has become far too easy to outright dismiss someone’s hard work. We live in a hyper-mediated age that moves too fast: all propositions are disposable, including the arts. Rabin, in taking each work on its own terms, does a service to both criticism and creativity.

Rabin’s own columns might, of course, fall prey to this disposable age. Today’s columns and blog posts are meant to be consumed quickly; although the best might find a life of new clicks in cyberspace, most are tomorrow’s virtual bird-cage liners. The blog-book is thus a tenuous grasp at some permeability–or at least respectability. My Year of Flops is fun, energetic, and insightful, but it does not bear sustained reading. The entries are best consumed one at time, probably between other tasks (or other books). It’s a great book for the john. Still, in an ideal library, My Year of Flops would stand squarely along side any other work of film criticism (it’s certainly sharper than anything by Leonard Maltin or Gene Shalit). Ultimately, Rabin does here what all great critics do–he makes a case for the works he’s appraising. He makes you want to see his Secret Successes and even the Fiascos (and, at times, even the Failures). I’ll even forgive him for making me watch The Apple. Recommended.

Vodpod videos no longer available.

More info here.

“His Face All Red” is a lovely, disturbing little self-contained webcomic by Em Carroll. Fratricide, an American gothic setting, and a horrifyingly ambiguous conclusion: what’s not to love? Read it here.