—No it’s all right . . . he’d brought his eyes up sharply from the loose collar of her blouseless suit, more the appeal of asking a favor than granting one in his tone—that was when he was old though, Wagner I mean, when Wagner was old and . . .

—Yes but that’s what you meant isn’t it, about creating an entirely different world when you write an opera, about asking the audience to suspend its belief in the . . .

—No not asking them making them, like that E flat chord that opens the Rhinegold goes on and on it goes on for a hundred and thirty-six bars until the idea that everything’s happening under water is more real than sitting in a hot plush seat with tight shoes on and . . .

—Mrs Joubert could I have a dime?

—I think you’ve had enough to eat Debby, we’re . . .

—It’s Linda.

—Linda yes I’m sorry, where’s your sweater.

—Over on the table, I don’t want to eat they said it costs a dime to go to the toilet here, you have to put a dime in to get in the . . .

—Yes yes all right if, oh thank you again we must be taking every penny you.

—No no it’s all right I’ve, I’d put some aside for the union and when they wouldn’t take me, when you say you’re a concert pianist they give you as hard a score as they can find there was a drummer there and all they asked for was give us a paradiddle . . .

—But why must you join at all, if you simply want to compose . . .

—No well since this teaching was, since it didn’t really work out too well I thought if I could find some work playing I could keep on with my . . .

—Mrs Jou . . .

—Here . . .! he thrust a dime at the figure shifting rapidly foot to foot beside her,—that I could keep working on my . . .

—But couldn’t you earn something writing music for, I don’t know but there must be somewhere you could . . .

—Yes well that’s what I did, what I’m doing I mean somebody I met there, a bass player, he was on standby he’s getting paid not to play at a Broadway show they say is a musical just because it . . .

—Mis . . .

—Excuse me, boys please! You’ve just had a dollar J R you don’t need . . .

—No I know, I just wondered if Mister Bast wants me to change some nickels from a dollar for him.

—Not, no but if you’d like something?

—Some, just some tea I think, I don’t feel awfully well . . .

—Yes wait, here . . . he peeled away a bill under the table.

—And he found you something? this bass player?

—No well yes sort of indirectly, he said he wanted to help me out and sent me to a place over on the West Side where they said they wanted some nothing music, three minutes of nothing music it’s for television or something, they said they had three minutes of talk on a track or a tape they needed music behind it but it couldn’t have any real form, anything distinctive about it any sound anything that would distract from this voice this, this message they called it, they . . .

—But of all things how absurd, paying a composer to . . .

—Yes well they didn’t, I couldn’t do it I mean, they were in a hurry they would have paid me three hundred dollars and I tried and all I could, everything I did they said was too . . .

—And that’s hardly what I meant, someone being paid not to play who sends you somewhere to write nothing mus . . .

—Well what do you think I . . .! he caught one hand back with the other,—I’m sorry I, three hundred dollars all I could think of was that concerto of Mozart’s the D-minor, that’s more than he got paid for the whole series and I couldn’t even . . .

—But I think it’s marvelous, that you couldn’t write their nothing music? I mean just because you can’t get paid to play Chopin or even write music that’s . . .

—No but I am though, I didn’t finish . . . he looked up from her fingertips touching his hands clenched there,—when I left somebody else there said he’d like to help me out and sent me downtown to see some dancers who want their own music for . . .

—Boys . . .! her hand was gone,—settle down! she called after the collision at the marbled cashier’s cage—I’m sorry, we . . .

—Do you like Chopin?

—Oh of course I do yes, that ballade the Ballade in G? it’s simply the most roman . . .

—In G-minor yes that’s on the program if I could get tickets would you, it’s next week would you like to go if I can get the tickets it’s a recital by . . .

—That’s awfully sweet Mister Bast I . . .

—No well I guess I, I mean you’re married I didn’t think of that I just . . .

—That’s hardly the reason no but, I’m just afraid I can’t, I’m . . .

—No that’s all right I just, I just thought you, you wanted some tea yes I’m sorry I’ll get it . . .

—Thank you I’d, oh be careful! she’d seized his wrist.

—No I’m all right . . . he came up slowly as her hand fell away,—I’ll get it . . . he righted the chair and stood looking, turned toward the figures huddled at a table near the telephone booths foreheads almost touching, hands churning coins.

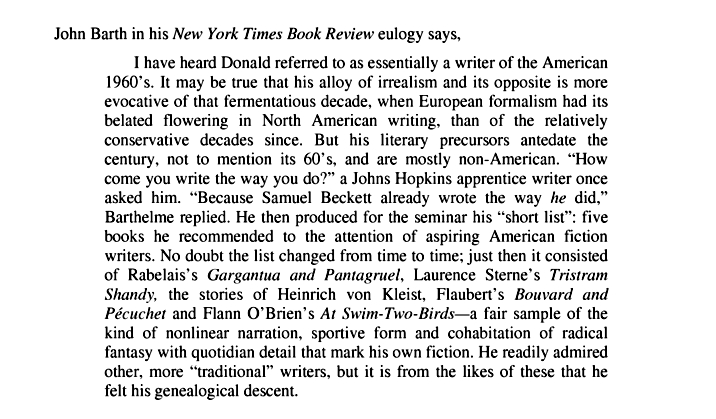

From Michael Thomas Hudgens’s Donald Barthelme, Postmodernist American Writer

From Michael Thomas Hudgens’s Donald Barthelme, Postmodernist American Writer