I downloaded the audiobook of version of William Gaddis’s first novel The Recognitions the other afternoon. The recording is 51 hours and 41 minutes long, and read by Nick Sullivan.

I am almost exactly six hours in, over halfway through the novel’s third chapter, an aural space that correlates to page 114 of my 956-page Penguin edition of the novel. In this particular moment, Wyatt Gwyon, the sorta-hero of The Recognitions, rants to his wife Esther about literary modernism. I stopped the book at that particular moment to find that particular passage in my copy of The Recognitions; it was particularly easy to find because I’d already dogeared that particular page.

I’m not sure if I dogeared that particular page when I first attempted The Recognitions in 2009 (I stalled out in the book’s second of three sections, somewhere around page 330 or so), or if I dogeared it on my second (and successful) reading in 2012. And while I’m tempted to focus on the passage I’ve just audited and then reread—a meta-moment where Wyatt raves about Modernism (even making a dig at Hemingway)—I’m more interested in making a few generalizations about the audiobook and the first chapter of The Recognitions.

So a few generalizations:

Nick Sullivan, who reads The Recognitions, is excellent. He’s expressive, and imbues the novel with a wonderful rhythm and vitality, differentiating the voices of each of the characters (no mean feat). I have audited Sullivan’s reading of Gaddis’s second novel JR, which is marvelous, and in many ways taught me to “read” that novel, which is told in almost entirely unattributed dialogue. I would strongly recommend anyone daunted by JR to read it in tandem with Sullivan’s audiobook version.

I would not, however, recommend using the audiobook of The Recognitions for a first go through (unless you intend to use the audiobook chapters after you’ve read the chapters yourself). The Recognitions simply contains a density of information unparalleled in almost any other novel I can think of). You’ll need to attend closely to it to parse the threads that matter in terms of the plot and the threads that are there to build the theme. And unless you’re a polyglot, hearing all the untranslated Latin, Spanish, Italian, and German read aloud does little for comprehension. No, I think The Recognitions is best read slowly, and ideally the reader should take the time to attend to its many allusions and motifs (Steven Moore’s online guide is invaluable here). This isn’t to say that readers need to get every damn little reference to enjoy and appreciate Gaddis’s novel—but it doesn’t hurt to try.

Still, there’ a lot in The Recognitions. The book is wonderful, a work of genius, and this is perhaps one of its faults—it suffers from First Novel Syndrome, the author cramming in all that he can, anxious that the audience Recognize Genius. Gaddis was young when it was published—just 34 (amazing). A much older Gaddis seemed to recognize this, saying the following in 1990:

So, in the work I’ve tried to do, in J R, especially the awful lot of description and narrative interference, as I see it now, in The Recognitions, where I am awfully pleased with information that I have come across and would like to share it with you-so I go on for two pages about, oh, I don’t know, the medieval Church,… the forgery, painting, theories of forgery and so forth, and descriptions, literally, of houses or landscapes. And when I got started on the second novel, which was J R, 726 pages, almost entirely my intention was to get the author out of there, to oblige the characters to create themselves and each other and their story, and all of it in dialogue

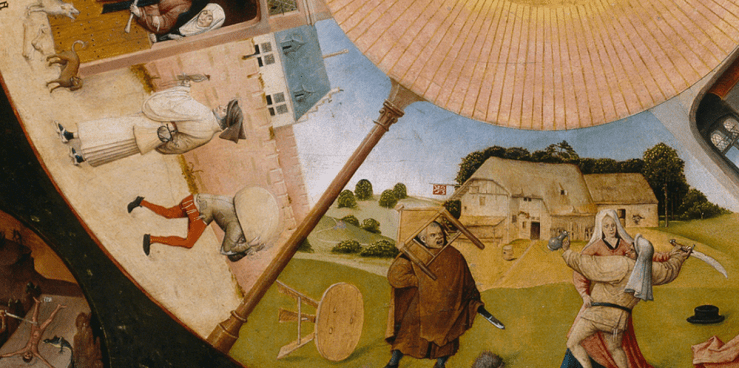

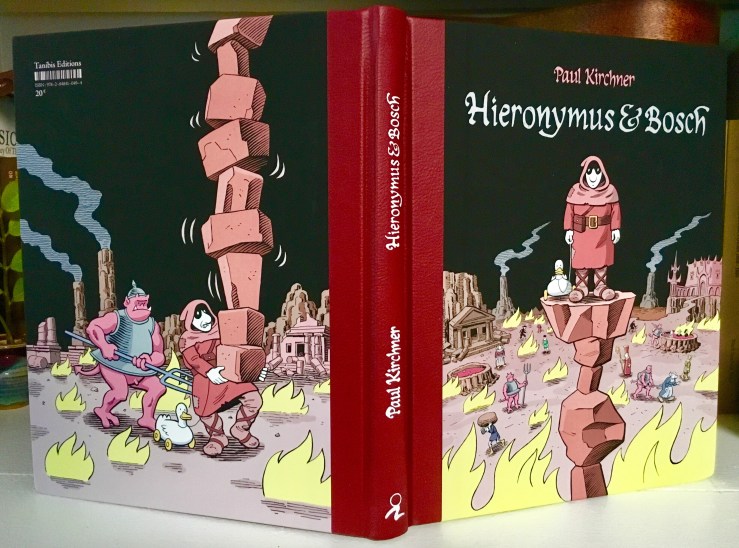

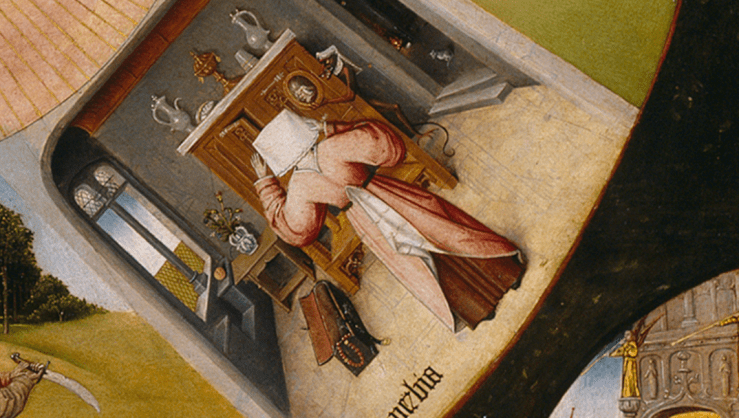

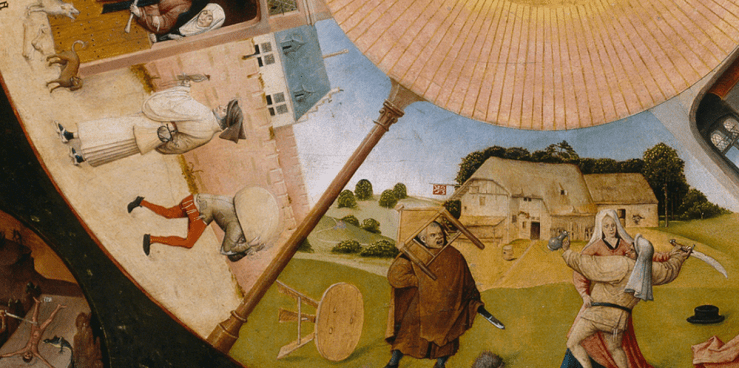

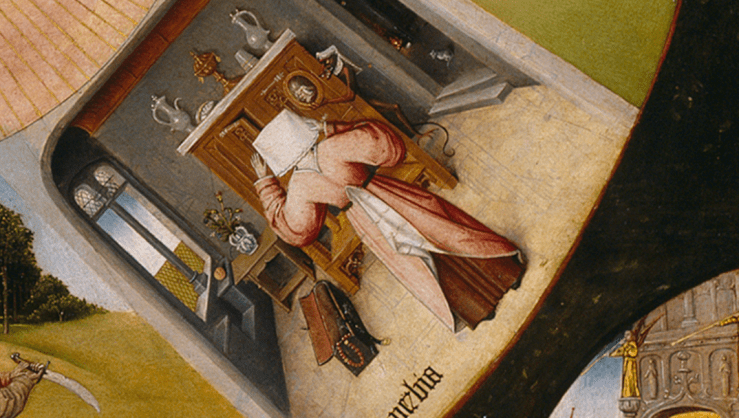

The first chapter of The Recognitions, the fruit of an author awfully pleased with information that he has come across, lays out an encyclopedic range of references to literature, art, religion, history, and every other manifestation of culture you might think of. The chapter is impossibly rich, and in some ways, the rest of the novel can never quite match it. Or rather, the rest of the novel teases out the material that Gaddis offers at its outset, threading the material into cables of plot and theme. Or maybe what I’m trying to say is, The first chapter of The Recognitions might be the best first chapter of any novel I can think of. At 62 pages, it’s almost a novella, and it can arguably stand on its own. Let me borrow my own summary of Chapter I from my 2009 write-up:

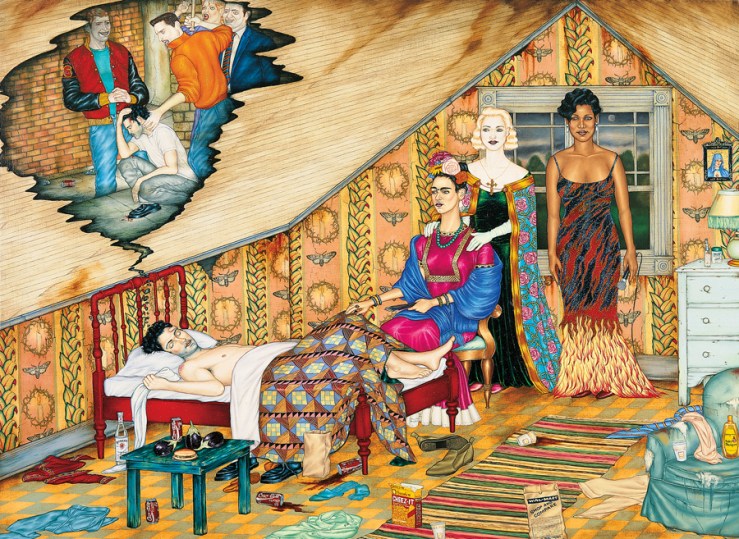

The first chapter is the best first chapter of any book I can remember reading in recent years. It tells the story of Rev. Gwyon looking for solace in the Catholic monasteries of Spain after his wife’s death at sea under the clumsy hands of a fugitive counterfeiter posing as a doctor (already, the book posits the inherent dangers of forgery, even as it complicates those dangers by asking who isn’t in some sense a phony). There’s a beautiful line Gaddis treads in the first chapter, between pain, despair, and melancholy and caustic humor, as Gwyon slowly realizes the false limits of his religion. The chapter continues to tell the story of young Wyatt, growing up under the stern care of his puritanical Aunt May, whose religious attitude is confounded by the increasingly erratic behavior of Wyatt’s often-absent father. While deathly ill, Wyatt teaches himself to paint by copying masterworks. He also attempts an original, a painting of his dead mother, but he cannot bear to finish it because, as he tells his father, “There’s something about . . . an unfinished piece of work . . . Where perfection is still possible. Because it’s there, it’s there all the time, all the time you work trying to uncover it.” This problem of originality, of Platonic perfection guides much of the novel’s critique on Modernism.

(The “novel’s critique on Modernism” — well, hey, that’s sort of how I came into this riff—stopping the audiobook six hours in to go track down pages 113-14, where Wyatt attacks Hemingway’s modern prose style). There’s more to the plot of Ch. 1, including a ritual sacrifice that’s easy to miss if you’re not paying close enough attention. There are also numerous references to pipe organs, planting the seeds of The Recognitions’ strange conclusion. But now of course is not the time to write about that conclusion; instead, I’ll conclude by remarking that I saw more of the novel’s form—including its conclusion—in its introduction than I had previously thought was there. And that’s the value in rereading a big novel—recognizing what we previously did not recognize.