Five Dream Units:

1. Knock the frog

2. Kick it out

3. Push it through

4. Cranial amphibian

5. Forget the happening

6. Your head/furnace

From “Riot in the Eye” by David Berman

Five Dream Units:

1. Knock the frog

2. Kick it out

3. Push it through

4. Cranial amphibian

5. Forget the happening

6. Your head/furnace

From “Riot in the Eye” by David Berman

It is the responsibility of society to let the poet be a poet

It is the responsibility of the poet to be a woman

It is the responsibility of the poets to stand on street corners giving out poems and beautifully written leaflets also leaflets they can hardly bear to look at because of the screaming rhetoric

It is the responsibility of the poet to be lazy, to hang out and prophesy

It is the responsibility of the poet not to pay war taxes

It is the responsibility of the poet to go in and out of ivory towers and two-room apartments on Avenue C and buckwheat fields and Army camps

It is the responsibility of the male poet to be a woman

It is the responsibility of the female poet to be a woman

It is the poet’s responsibility to speak truth to power, as the Quakers say

It is the poet’s responsibility to learn the truth from the powerless

It is the responsibility of the poet to say many times: There is no freedom without justice and this means economic justice and love justice

It is the responsibility of the poet to sing this in all the original and traditional tunes of singing and telling poems

It is the responsibility of the poet to listen to gossip and pass it on in the way storytellers decant the story of life

There is no freedom without fear and bravery. There is no freedom unless earth and air and water continue and children also continue

It is the responsibility of the poet to be a woman, to keep an eye on this world and cry out like Cassandra, but be listened to this time.

From Grace Paley’s 1986 essay “Poetry and the Women of the World.” Collected in Just as I Thought.

Picked up Christine Brooke-Rose’s 1984 postmodern novel Amalgamemnon and the Grove Press collection of Three Exemplary Novels by Miguel de Unamuno the other day. Those three exemplary novels are Marquis of Lubria; Two Mothers; and Nothing Less Than a Man, in translation by Angel Flores. It’s an older edition; Grove Press’s contemporary copy offers the following:

In Two Mothers, the demonic will of a woman runs amok in a whirlwind of maternal power, and in The Marquis of Lumbria, another unforgettable heroine steers a violent course through the dense sea of tradition. By contrast, Nothing Less Than a Man, Unamuno’s most forceful piece of writing, focuses on a truly Nietzchean hero, a man who embodies human will deprived of spiritual strength.

And here’s a bit on Brooke-Rose’s Amalgamemnon from Susie E. Hawkins’ essay “Innovation/History/Politics: Reading Christine Brooke-Rose’s Amalgamemnon” from the Spring 1991 issue of Contemporary Literature:

While the title signals possible mythic revisions of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, such anticipations on the reader’s part prove to be utterly unfounded. To begin with, there is no “story” as such, there are no “characters,” no “plot,” no “conflict,” and certainly no “climax.” In addition, the fiction is cast entirely in the future and conditional tenses with a few imperatives and subjunctives thrown in. Although Amalgamemnon exhibits few remnants of a traditional narrative desire for unity, presence, psychological accuracy, closure, and so forth, it does do what most innovative writing should do: it challenges the audience in terms of accustomed modes of perception, interpretation, and reading strategies – in short, challenges readerly ideology. In part, this text enacts such a challenge by performing itself, by “being about” language, by being a performance. The text becomes a space in which a cacophony of voices, or discursive amplifications, or babble, or little stories – whichever term best suits — enact their own sounding.

From Djuna Barnes’s Ladies Almanack.

At the next class meeting, Everett informed us that we would be taking an essay examination that day.

“You said ‘no tests,’ ” one of the women said.

“This is an examination,” Everett said.

“That doesn’t make sense,” she said.

“Well, be that as it may.” He passed around the exam. “There are three questions, and I urge you to divide your time unevenly on them, as they are of equal value. Since one hundred is not divisible by three, there is no way for you to achieve a perfect score. Unless of course we decide that ninety-nine is a perfect score, and I wouldn’t mind that at all.”

The examination:

1) Imagine a radical and formidable contextualism that derives from a hypostatization of language and that it anticipates a liquefied language, a language that exists only in its mode of streaming. How is a speaker to avoid the pull into the whirl of this nonoriented stream of language?

2) Is the I one’s body? Is fantasy the specular image? And what does this have to do with the Borromean knot? In other words, why is there no symptom too big for its britches?

3) How might it feel to burn with missionary zeal? Don’t be shy in your answer.

We students looked at each other with varying degrees of confusion, panic, and anger. And like idiots, we set to work. At least they did. I read the questions over and over and after the numbers 1 and 2 on my paper I wrote, I don’t know. After the number 3 I wrote, Awful, then added, damn it.

From Percival Everett’s novel I Am Not Sidney Poitier.

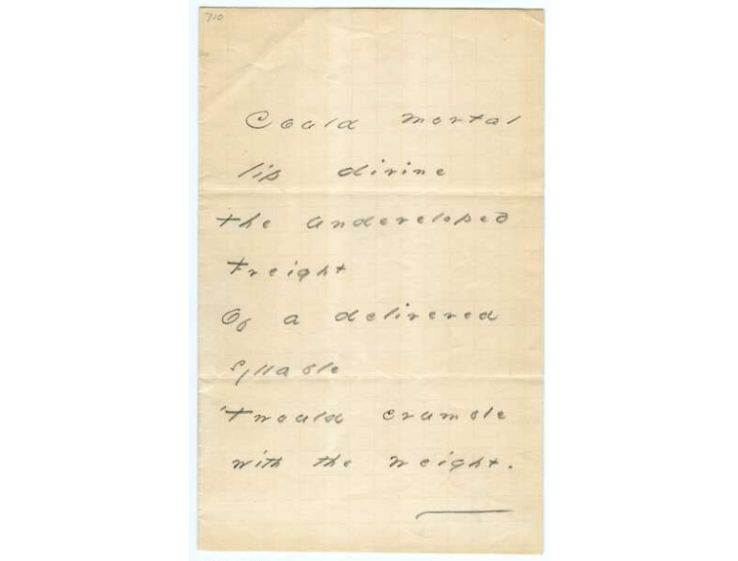

Could mortal lip divine

The undeveloped freight

Of a delivered syllable,

‘T would crumble with the weight.

Emily Dickinson

So I started in on Tomoé Hill’s Songs for Olympia last night—poetic, critical, personal, strange in the right ways. Here’s publisher Sagging Meniscus’ blurb:

In the twilight of life, a black ribbon emerges from a frame and coils itself inside the mind of one of the great French chroniclers of the internal. Across the world, a young girl stares at an image in a book: a woman, naked but for slippers, jewels, and the same ribbon which so captivates the writer. At opposite poles of experience, one follows the ribbon as it winds its way round longings, regrets, and contemplations; the other, at the beginning of development and yet to discover the world, traces the ribbon with a finger, not realising how it will imprint itself upon her.

Years later, the girl—now woman—encounters the ribbon face to face and on the page. Manet’s Olympia and the words of Michel Leiris come together, and an imaginary conversation ensues. It will be a collision and collaboration of sensorial memories and observations on everything from desire and illness to writing and grief. These frames are used to examine both interlocutors; simultaneously, a frame of another sort is removed from Olympia and her artistic kin. Everything from her flowers, Louise Bourgeois’s Sainte Sébastienne, and Francis Bacon’s Henrietta Moraes are reimagined and given new regard.

Songs for Olympia, written in the form of a response to Michel Leiris’s The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat, itself a highly personal response to Manet’s painting, is an ode to the both the ribbon and the memory: what leads us to constantly rediscover ourselves and a world so easily assumed as viewed through a single frame.

“Monkey Junk”

by

Zora Neale Hurston

1. And it came to pass in those days that one dwelt in the land of the Harlemites who thought that he knew all the law and the prophets.

2. Also when he arose in the morning and at noonday his mouth flew open and he said, “Verily, I am a wise guy. I knoweth all about women.”

3. And in the cool of the evening he saith and uttereth, “I know all that there is about the females. Verily, I shall not let myself be married.”

4. Thus he counselled within his liver for he was persuaded that merry maidens were like unto death for love of him.

5. But none desired him.

6. And in that same year a maiden gazeth upon his checkbook and she coveted it.

7. Then became she coy and sweet with flattery and he swalloweth the bait.

8. And in that same month they became man and wife.

9. Then did he make a joyful noise saying, “Behold, I have chosen a wife, yea verily a maiden I have exalted above all others, for see I have wed her.”

10. And he gave praises loudly unto the Lord saying, “I thank thee that I am not as other men—stupid and blind and imposed upon by every female that listeth. Behold how diligently I have sought and winnowed out the chaff from the wheat! Verily have I chosen well, and she shalt be rewarded for her virtue, for I shall approve and honor her.”

11. And for an year did he wooed her with his shekels and comfort her with his checkbook and she endured him.

12. Then did his hand grow weary of check signing and he slackened his speed.

13. Then did his pearl of great price form the acquaintance of many men and they prospered her.

14. Then did he wax wrathful in his heart because other men posed the tongue into the cheek and snickered behind the hand as he passed, saying, “Verily his head is decorated with the horns, he that is so wise and knoweth all the law and the profits.”

16. And he chided his wife saying, “How now dost thou let others less worthy bite thy husband in the back? Verily now I am sore and I meaneth not maybe.”

17. But she answered him laughingly saying, “Speak not out of turn. Thou wast made to sign checks, not to make love signs. Go now, and broil thyself an radish.”

18. Then answered he, “Thy tongue doth drip sassiness and thy tonsils impudence, know ye not that I shall leave thee?”

19. But she answered him with much gall, “Thou canst not do better than to go—but see that thou leave behind thee many signed checks.”

20. And when he heard these things did he gnash his teeth and sweat great hunks of sweat.

21. And he answered, “Verily I am through with thee—thou canst NOT snore in my ear no more.

22. Then placeth she her hands upon the hip and sayeth, “Let not that lie get out, for thou art NOT through with me.”

23. And he answered her saying, “Thou has flirted copiously and surely the backbiters shall sign thy checks henceforth—for I am through with thee.”

24. But she answered him, “Nay, thou art not through with me—for I am a darned sweet woman and thou knowest it. Don’t let that lie get out. Thou shalt never be through with me as long as thou hath bucks.”

25. “Thou art very dumb for now that I, thy husband, knoweth that thou art a flirt, making glad the heart of back-biters, I shall support thee no more—for verily know I ALL the law and the profits thereof.”

26. Then answered she with a great sassiness of tongue, “Neither shalt not deny me thy shekels for I shall seek them in law, yea shall I lift up my voice and the lawyers and judges shall hear my plea and thou shalt pay dearly. For, verily, they permit no turpitudinous mama to suffer. Selah and amen.”

27. But he laughed at her saying hey! hey! hey! many times for verily he considered with his kidneys that he knew his rights.

28. Then went she forth to the market place and sought the places that deal in fine raiment and bought much fine linen, yea lingerie and hosiery of fine silk, for she knew in her heart that she must sit in the seat of a witness and hear testimony to many things lest she get no alimony.

29. Even of French garters bought she the finest.

30. Then hastened she away to the houses where sat Pharisees and Sadducees and those who know the law and the profits, and one among them was named Miles Paige, him being a young man of a fair countenance.

31. And she wore her fine raiment and wept mightily as she told of her wrongs.

32. But he said unto her, “Thou has not much of a case, but I shall try it for thee. But practice not upon me neither with tears nor with hosiery—for verily I be not a doty juryman. Save thy raiment for the courts.”

33. But her husband sought no counsel for he said, “Surely she hath sinned against me—even cheated most vehemently. Shall not the court rebuke her when I shall tell of it. For verily I know also the law.”

34. Then came the officer of the court and said, “Thou shalt give thy wife temporary alimony of fifty shekels until the trial cometh.”

35. And he was wrathful but he wagged the head and said, “I pay now, but after the trial I shall pay no more. He that laughest last is worth two in the bush.”

36. And entered he boldly into the courts of law and sat down at the trial. And his wife and her lawyer came also.

37. But he looked upon the young man and laughed for Miles Paige had yet no beard and the husband looked upon him with scorn, even as Goliath looked upon David.

38. And the judge sat upon the high seat and the jury sat in the box and many came to see and to hear, and the husband rejoiced within his heart for the multitude would hear him speak and confound the learned doctors.

39. Then called he witnesses and they did testify that the wife was an flirt. And they sat upon the stand again and the young Pharisee, even Paige questioned them, and verily they were steadfast.

40. Then did the husband rejoice exceedingly and ascended the stand and testified of his great goodness unto his spouse.

41. And when the young lawyer asked no questions he waxed stiff necked for he divined that he was afraid.

42. And the young man led the wife upon the stand and she sat upon the chair of witnesses and bear testimony.

43. And she gladdened the eyes of the jury and the judge leaned down from his high seat and beamed upon her for verily she was some brown.

44. And she turned soulful eyes about her and all men yearned to fight for her.

45. Then did she testify and cross the knees, even the silk covered joints, and weep. For verily she spoke of great evils visited upon her.

46. And the young Pharisee questioned her gently and the jury leaneth forward to catch every word which fell from her lips.

47. For verily her lips were worth it.

48. Then did they all glare upon the husband; yea, the judge and jury frowned upon the wretch, and would have choked him.

49. And when the testimony was finished and she had descended from the stand, did the young man, even Miles Paige stand before the jury and exhort them.

50. Saying, “When in the course of human events, Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou and how come what for?” And many other sayings of exceeding wiseness.

51. Then began the jury to foam at the mouth and went the judge into centrance. Moreover made the lawyer many gestures which confounded the multitude, and many cried, “Amen” to his sayings.

52. And when he had left off speaking then did the jury cry out “Alimony (which being interpreted means all his jack) aplenty!”

53. And the judge was pleased and said “An hundred shekels per month.”

54. Moreover did he fine the husband heavily for his cruelties and abuses and his witnesses for perjury.

55. Then did the multitude rejoice and say “Great is Miles Paige, and mighty is the judge and jury.”

56. And then did the husband rend his garments and cover his head with ashes for he was undone.

57. But privately he went to her and said, “Surely, thou has tricked me and I am undone by thy guile. Wherefore, now should I not smite thee, even mash thee in the mouth with my fist?”

58. And she answered him haughtily saying, “Did I not say that thou wast a dumb cluck? Go to, now, thou had better not touch this good brown skin.”

59. And he full of anger spoke unto her, “But I shall surely smite thee in the nose—how doth old heavy hitting papa talk?”

60. And she made answer unto him, “Thou shalt surely go to the cooler if thou stick thy rusty fist in my face, for I shall holler like a pretty white woman.”

61. And he desisted. And after many days did he receive a letter saying “Go to the monkeys, thou hunk of mud, and learn things and be wise.”

62. And he returned unto Alabama to pick cotton.

Selah.

Continue reading “Read Zora Neale Hurston’s short story “Monkey Junk””

A few weeks ago, I picked up Anthony Kerrigan’s translation of Miguel de Unamuno’s Abel Sanchez and Other Stories based on its cover and the blurb on its back. I wound up reading the shortest of the three tales, “The Madness of Dr. Montarco,” that night. The story’s plot is somewhat simple: A doctor moves to a new town and resumes his bad habit of writing fiction. He slowly goes insane as his readers (and patients) query him about the meaning of his stories, and he’s eventually committed to an asylum. The tale’s style evokes Edgar Allan Poe’s paranoia and finds an echo in Roberto Bolaño’s horror/comedy fits. The novella that makes up the bulk of the collection is Abel Sanchez, a Cain-Abel story that features one of literature’s greatest haters, a doctor named Joaquin who grows to hate his figurative brother, the painter Abel. Sad and funny, this 1917 novella feels contemporary with Kafka and points towards the existentialist novels of Albert Camus. (I’m saving the last tale, “Saint Manuel Bueno, Martyr,” for a later day.)

I’m near the end of Iain Banks’s second novel, Walking on Glass (1985), which so far follows three separate narrative tracks: one focusing on an art student pining after an enigmatic beauty; one following an apparent paranoid-schizophrenic who believes himself to be a secret agent of some sort from another galaxy, imprisoned on earth; and one revolving around a fantastical castle where two opposing warriors, trapped in ancient bodies, play bizarre table top games while they try to solve an unsolvable riddle. I should finish later tonight, I think, and while there are some wonderful and funny passages, I’m not sure if Banks will stick the landing here. My gut tells me his debut novel The Wasp Factory is a stronger effort.

I’ve been soaking in Sorokin lately, thanks to his American translator Max Lawton, with whom I’ve been conducting an email-based interview over the past few months. Max had kindly shared some of his manuscripts with me, including an earlier draft of the story collection published as Red Pyramid. I’ve found myself going through the collection again now that it’s in print from NYRB—skipping around a bit (but as usual with most story collections, likely leaving at least one tale for the future.)

I very much enjoyed Gerhard Rühm’s Cake & Prostheses (in translation by Alexander Booth)—sexy, surreal, silly, and profound. Lovely little thought experiments and longer meditations into the weird.

I really enjoyed Debbie Urbanski’s debut novel After World. The novel’s “plot,” such as it is, addresses the end of the world: Or not the end of the world, but the end of the world of humans: Or the beginning of a new world, where consciousness might maybe could who the fuck actually can say be uploaded to a virtual after world. After World is a pastiche of forms, but dominated by the narrator [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc whose task is to reimagine the life of Sen Anon, one of the final humans to live and die on earth—and the last human to be archived/translated/transported into the Digital Human Archive Project. This ark will carry humanity…somewhere. [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc creates Sen’s archive through a number of sources, including drones, cameras, Sen’s own diary, and a host of ancillary materials. [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc also crafts the story, drawing explicitly on the tropes and forms of dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature. After World is thus explicitly and formally metatextual; [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc archives the life of Sen Anon, last witness to the old world and Urbanski archives the dystopian and post-apocalyptic pop narratives that populate bestseller lists and serve as the basis for Hollywood hits. [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc namechecks a number of these authors and novels, including Octavia Butler, Margaret Atwood, and Ann Leckie, while Sen Anon holds tight to two keystone texts: Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves and Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. But the end-of-the-world novel it most reminded me of was David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. Even as it works to a truly human finale, Urbanski’s novel is spare: post-postmodern, post-apocalyptic, and post-YA. Good stuff.

Speaking of: Carole Masso’s 1991 novel Ava also strongly reminded me of Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. Its controlling intelligence is the titular Ava, dying too young of cancer. The novel is an elliptical assemblage of quips, quotes, observations, dream thoughts, and other lovely sad beautiful bits. Masso creates a feeling, not a story; or rather a story felt, intuited through fragmented language, experienced.

I continue to pick my way through Frederick Karl’s American Fictions. He is going to make me buy Joseph McElroy’s 1974 novel Lookout Cartridge.

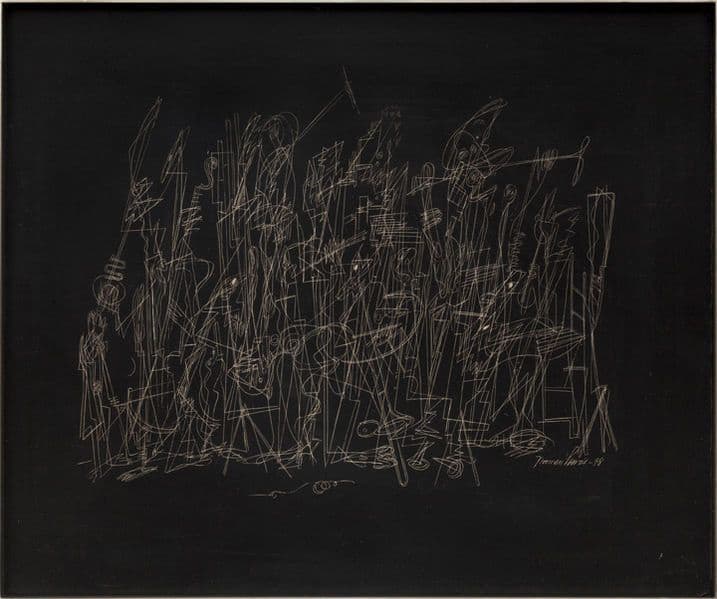

Jazz Band, 1948 by Norman Lewis (1909-1979)

Patrick Langley’s novel The Variations is new from NYRB. Their blurb:

Selda Heddle, a famously reclusive composer, is found dead in a snowy field near her Cornish home. She was educated at Agnes’s Hospice for Acoustically Gifted Children, which for centuries has offered its young wards a grounding in the gift—an inherited ability to tune into the voices and sounds of the past.

When she dies, Selda’s gift passes down to her grandson Wolf, who must make sense of her legacy, and learn to live with the newly unleashed voices in his head. Ambitious and exhilarating, The Variations is a novel of startling originality about music and the difficulty—or impossibility—of living with the past.

“Strictly Business”

by

Chester Himes

What his real name was, no one knew or cared.

At various times, during his career of assaults, homicides, and murders, he had been booked under the names of Patterson, Hopkins, Smith, Reilly, Sanderson, and probably a dozen others.

People called him “Sure.”

He was twenty-five years old, five feet, eleven inches tall, weighed one-eighty-seven, had light straw-colored hair and wide, slightly hunched shoulders. His pale blue eyes were round and flat as poker chips, and his smooth, white face was wooden.

He wore loose fitting, double-breasted, drape model suits, and carried his gun in a shoulder sling.

His business was murder.

At that time he was working for Big Angelo Satulla, head of the numbers mob.

The way Big Angelo’s mob operated was strictly on the muscle. They took their cut in front—forty per cent gross, win, lose, or draw—and the colored fellows operated the business on what was left.

Most of the fellows in the mob were relatives of Big Angelo’s. There were about forty of them and they split a million or more a year.

Sure was there because Big Angelo didn’t trust any of his relatives around the corner. He was on a straight salary of two hundred and fifty dollars a week, and got a bonus of a grand for a job.

Business was good. He could remember when at eighteen he had worked for fifty bucks a throw, and if you got caught with the body you were just S.O.L.

He and Big Angelo were at the night drawing of the B&B house, a little before midnight, when the word came about Hot Papa Shapiro. Pipe Jimmy Sciria, the stooge Big Angelo had posted in the hotel as a bellhop to keep tabs on Hot Papa, called and said it looked as if Hot Papa was going to spill because a police escort had just pulled up to the hotel to take him down to the court house where the Grand Jury was holding night sessions during the DA’s racket-busting investigation.

Big Angelo had had the feeling all along that Hot Papa had rat in his blood, but now when he got the word that the spill was on the turn, he went green as summer salad. Continue reading ““Strictly Business,” a short story by Chester Himes”

Witness, 1968 by Benny Andrews (1930-2006)

A Youth, 1934 by Hale Woodruff (1900-1980)

Last week I got physical copies of two forthcoming Vladimir Sorokin books, both translated by Max Lawton and both published by NYRB.

Sorokin’s 1999 novel Blue Lard is one of the strangest and most daring books I’ve ever read—simultaneously compelling and repulsive, confounding and rewarding, a novel that twists from scenario to scenario, occasionally looking back at its reader to holler, Hey, catch up! Its English-language translator Max Lawton was kind enough to share his manuscript for Blue Lard with me during a long and enjoyable interview we undertook in the summer of 2022 (around the time of the publication of his translation of Sorokin’s 2014 novel Telluria). While Max was, on one hand, trying to help me better understand Sorokin in context by sharing Blue Lard with me, on the other, I think he was mostly trying to share a really fucking great book with someone who might like it—which is the kind of love one could only hope for from a translator. From our first interview:

BIBLIOKLEPT: Blue Lard might benefit from a brief introduction, so I’ll offer my unasked-for services: “This shit is wild. Just go for it. Don’t try to make it do what you think a novel should be doing. Just go with it.”

ML: BLUE LARD is about that state of confusion—ontological and linguistic—as it unfurls. To introduce the text beyond something like your pithy statement above might be a disservice to the book. The reader should be confused and it should hurt—then feel fucking good ….when reading Sorokin, we’re fucking nostrils with forked dicks (or—getting our nostrils fucked by the same).

The book’s real introduction is the Nietzsche quote at the beginning.

Does FINNEGANS WAKE need an introduction? Is one even possible?

I loved BLUE LARD when I first read it precisely because I had no point of reference for understanding it

Hey but so well guess what! I have another interview with Max on deck! Here’s a bit of a teaser from that interview, again on Blue Lard:

Like TELLURIA, BLUE LARD is all about textures: literary, historical, ideological… However, unlike TELLURIA, BLUE LARD has a telos to it—an endpoint. I am firmly of the belief that BLUE LARD is Vladimir’s best novel. He had taken a long break from prose (about 7 years) before writing it, so this text simply burst forth from him and ended up as a neat showcase of all of his aesthetic preoccupations, but lorded over by an edifice that has proportions none too short of classically harmonious. What should readers expect… hmm.. the first section is rather challenging. One needs to surf its wave and not expect full comprehension. There is a glossary of Chinese words and neologisms at the back of the book, but I’m not sure it’s worth consulting in the expectation of further understanding. The middle section of the book—characterized by a faux-archaic language—is also terribly strange, but with fewer neologisms. The last section of the book—an alternate iteration of Post-WWII Europe—is formally very smooth, but insanely transgressive in terms of content. And I haven’t even mentioned the rather unorthodox parodies of Russian classics in the novel’s first section! What should readers expect? In short: to have their minds blown!

Red Pyramid offers an overview of Sorokin’s development as a writer, collecting stories composed between 1981 and 2018. From Will Self’s introduction:

Fundamental to the fiction of Vladimir Sorokin is not the pornography his detractors accuse him of producing but the paradoxical topologies his carefully spun tales evoke. Each of his stories is a sort of mutant Möbius strip, in which to follow the narrative is to experience the real and the fantastic as simultaneously opposed and coextensive. There comes a point—it may be early on; it may be comparatively late-when the strictures of orthodox plotting seem to overwhelm its author, such that idiom and plain speech converge even as events spiral ineluctably out of human control.

And here’s Joy Williams’ blurb:

Extravagant, remarkable, politically and socially devastating, the tone and style without precedent, the parables merciless, the nightmares beyond outrance, the violence unparalleled, these stories, translated with fearless agility by Max Lawton, showcase the great novelist Vladimir Sorokin at his divinely disturbing best.

(Williams deploys the word outrance here, which was new to me, and I think it fits.)