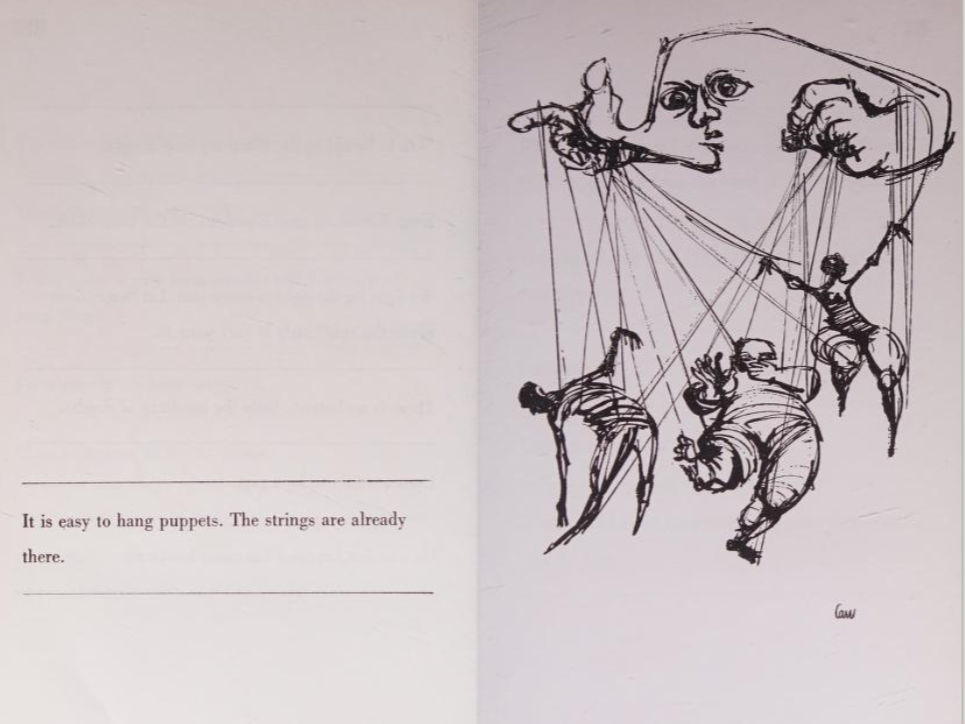

An aphorism from Stanislaw J. Lec’s Unkempt Thoughts with an illustration by Barbara Carr. Translation by Jacek Galazka.

An aphorism from Stanislaw J. Lec’s Unkempt Thoughts with an illustration by Barbara Carr. Translation by Jacek Galazka.

I want to comment on the themes and style of William Gaddis’s fourth novel, 1994’s A Frolic of His Own, and I’d like to do so without the burden of summarizing its byzantine plot, so I’ll crib from Steven Moore’s contemporary review of the novel that was first published in the Spring 1994 issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction. Although he initially protests that the “plot is too wonderfully complex to summarize,” Moore nevertheless offers a concise precis. Moore writes that A Frolic of His Own

…concerns an interlocking set of lawsuits involving the Crease family: Oscar, a historian and playwright; Christina, his stepsister and married to a lawyer named Harry Lutz; and their father Judge Thomas Crease, presiding over two cases in Virginia during the course of the novel. The story unfolds by way of Gaddis’s trademark dialogue but also by various legal opinions, brilliantly rendered in the majestic language of the law.

Law, one of the major themes of the novel, is announced in its opening lines: “Justice? —You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law.” A Frolic of His Own delves into the intersection of justice, law, art, theft, and compensation, all while foregrounding language as the mediating force of not just these nebulous concepts, but the medium, of course, of the novel itself. “What do you think the law is, that’s all it is, language,” the exasperated lawyer Harry declaims to his wife Christina.

Language is always destabilized and destabilizing in A Frolic of His Own. Gaddis lards the novel with mistakes, misinterpretations, and muddles of every mixture. Characters repeatedly fail to communicate clearly with each other, their dialogue twisting into new territories before they’ve mapped out their present concerns. A Frolic reads as linguistic channel surfing, an addled mind constantly turning the dial before a thought can fully land.

The effect of this linguistic channel surfing at times stuns and overwhelms the reader, approximating the noise of modern language that Gaddis’s heroes so often rail against, even as they participate in and create more of this noise. It’s worth sharing a paragraph in full to offer a sense of what Gaddis is doing in A Frolic of His Own. Here, Christina takes a phone call from her husband Harry, while her brother Oscar (who is slowly going mad) watches the evening news:

—Has Harry called? And when it finally rang —We’re fine, did you get to that new doctor? Well whatever you call him, you… I know that Harry but you’ve simply got to make time, if you don’t you’re going to end up like… that’s exactly what I mean, he’s sitting right here waiting for the evening news to whet his appetite for supper, I mean I can’t take care of both of you can I? Scenes of mayhem from Londonderry to Chandigarh, an overweight family rowing down main street in a freak flood in Ohio, a molasses truck overturned on the Jersey Turnpike, gunfire, stabbings, flaming police cars and blazing ambulances celebrating a league basketball championship in Detroit interspersed with a decrepit grinning couple on a bed that warped and heaved at the touch of a button —because they offered him a settlement Harry, almost a quarter million dollars but of course he insists on going ahead with the case or rather Mister Basie does, he was out here for… what? The Stars and Bars unfurled in a hail of rocks and beer cans showering the guttering remnants of a candlelight vigil—but if you can just try to be patient with her Harry, you know her mother just died and she’s been in an awful state trying to… to what? Oscar will you turn that down! that now she wants you to help her break her mother’s will? I don’t see what… well they never really got on after her mother was converted by that wildeyed Bishop Sheed was it? a million years ago convincing her that it was more exclusive with Clare Luce and all that after the wads of money she’d been giving St Bartholomew’s with these millions of Catholics jamming every slum you can think of if you call that exclusive, she…—Look! Christina look! Placards brandishing KEEP GOD IN AMERICA, MURDERER come quickly! and caught in the emergency vehicles’ floodlights towering over it all the jagged thrust of —that, that Szyrk thing that, look!

The noisy force of mass-mediated language threatens to overwhelm the reader, whom Gaddis challenges to make meaning of his mess. Later, Christina sums up the problem: “I mean you talk about language how everything’s language it seems all that language does is drive us apart.” Naive Oscar, whose multiple lawsuits initiate the plot of A Frolic, tries to clarify the problem of language in his own way too: “—Isn’t that what language is for? to say what you mean? That’s why man invented language, isn’t it? so we can say what we mean?” But the events that Gaddis arranges in his novel suggest that the answer is, Not quite. There’s only one language all Americans understand—money:

—You want to sue them for damages, that’s money isn’t it?

—Because that’s the only damn language they understand! …Steal poetry what do you sue them for, poetry? …Two hundred hours teaching Yeats to the fourth grade?

Oscar’s complaint is the apparent plagiarism of his Civil War play Once at Antietam by a major Hollywood studio that has turned it into a “piece of trash” called The Blood in the Red White and Blue. Gaddis includes large sections of Oscar’s play in A Frolic of His Own, often having various characters (including its author) stop to make critical remarks. Here, Gaddis has actually cannibalized parts of a play he wrote in the late 1950s after he’d finished The Recognitions. He was unable to get Once at Antietam produced or published. In a 1961 letter, he admitted that “Now it reads heavy-handed, obvious, over-explained, oppressive,” adding that there might be some value somewhere in the work “but the vital problem remains, to extract it, to lift out something with a life of its own, give it wings, release it.” A Frolic of His Own may, on one hand, “release” Gaddis’s old play, but it denies it any life of its own. The play is bound within the text proper, incomplete, riddled with elisions, terminally unfinished.

It also comes to light (via a lengthy legal deposition) that Oscar (and perhaps the younger Gaddis?) has plagiarized large sections of his play, notably from Plato’s Republic. Oscar pleads that his plagiarisms are justified—they are art. But in A Frolic of His Own, “it all evaporates into language confronted by language turning language itself into theory till it’s not about what it’s about it’s only about itself turned into a mere plaything.”

Language is, of course, Gaddis’s plaything, and his novel repeatedly underlines its own textuality without the preciousness that sometimes afflicts postmodernist writing. For all his innovations and experimentation with form, Gaddis here and elsewhere is at his core a traditionalist like his hero T.S. Eliot. And like Eliot, he seeks to pick up the detritus of culture and meld it into something new, all while attacking the hollow men who run America. There’s more than just crankiness here: There is howling and bleating and often despair. There’s no justice for our characters, but at the same time, they hardly deserve any. For all their apparent cares and worries, these rich, venal, petty characters are ultimately, to borrow a phrase from another book, careless people, leaving messes for others to clean up (often quite literally). The satire bites; it’s rightfully mean-spirited, caustic, and bitter.

As such, A Frolic of His Own, for all its humor, is often very bleak. It also becomes increasingly claustrophobic. The characters get stuck in their language loops; the only way out seems to be madness or death. Gaddis’s writing had long evoked suffocating domestic spaces, whether it was the paper-stuffed 96th Street apartment shared by Bast, Eigen, and Gibbs in 1975’s J R or the haunted house of 1985’s Carpenter’s Gothic. A Frolic of His Own takes the madness to another level, setting the stage for the monolingual stasis of his final work, Agapē Agape.

Even if its cramped quarters are often gloomy and crammed with sharp objects, there’s a zaniness to the linguistic channel surfing of A Frolic that propels its fractured narrative forward. “The rest of it’s opera,” repeats Harry throughout, calling attention to the novel’s satirical histrionics. “It’s a farce,” repeats Oscar, pointing to both his own legal cases and his family history. As A Frolic progresses, its farcical twists become more and more bizarre, yet Gaddis always ties his loose ends. The modern world he satirizes is absurd, but it is real.

The realism Gaddis evokes in A Frolic centers around food and shelter. The action is confined primarily to the dilapidated old Crease estate, with its family (in ever-shifting configurations) frequently trying to feed themselves: “We’ve got to get some food in the house” becomes a mantra. Poor privileged half-siblings Oscar and Christina can hardly shop for themselves, let alone cook.

They are very adroit at drinking, however. As the novel careens towards madness, the half-siblings respond by hitting the booze. Consumption runs throughout the novel, presaged in its domestic-but-dooming epigraph, a recollection of something Thoreau said to Emerson while they were walking:

What you seek in vain for, half your life, one day you come full upon, all the family at dinner. You seek it like a dream, and as soon as you find it you become its prey.

Gaddis was fond of repurposing language, and first used the lines in his first novel, 1955’s The Recognitions. The last line of the epigraph, which finds the seeker become prey to his own dream, seems to me now to further highlight A Frolic’s themes of consumption—taboo consumption: cannibalism.

Very early in the novel, the narrator calls attention to Oscar’s copy of George Fitzhugh’s 1857 defense of slavery, Cannibals All! The phrase “cannibals all” is then inverted near the very end of the novel, when a former lawyer, in the hopes of perpetrating an insurance scam, wedges his foot in Oscar’s door: “they’re cannibals Mister Crease, they’re all cannibals,” the former lawyer insists, referring broadly to the insurance industry (he’ll later extend the term to those working in the real estate market in particular and humanity in general).

These direct inversions—cannibals-all/all-cannibals—bookend A Frolic of His Own, neatly encasing the metaphorical cannibalism that runs through the novel. Gaddis depicts a “dog eat dog” world (full of literal dead dogs) ruled by venal consumption. Family members cannibalize family members, law cannibalizes art, texts cannibalize texts. “When the food supply runs out and the only ones around are your own species, why go hungry?” interjects the narrator of a nature documentary that Oscar watches absentmindedly. Harry puts it succinctly:

That’s…what this whole country’s really all about? tens of millions out there with their candy and beer cans and this inexhaustible appetite for being entertained? Anything they can get their hands on…

Gaddis depicts a world where all attempts at culture and art are ultimately cannibalized and excreted by capital. In one of the novel’s goofiest and meanest gags, an entrepreneur seeks to exploit the highly-publicized death of Spot, a dog trapped and then zapped in an ugly postmodernist sculpture. The huckster, capitalizing on the public’s love for Spot, creates “Hiawatha’s Magic Mittens…labeled ‘Genuine Simulated Spotskin® Wear ‘Em With The Furside Outside.'”

“Hiawatha’s Magic Mittens” might seem like a throwaway joke, but the joke is nevertheless part of the novel’s theme of cannibalized culture. Those familiar with the legend of Hiawatha may recall that in many versions, Hiawatha practices ritual cannibalism until he is converted by the Great Peacemaker Deganawida. After his conversion, Hiawatha ceases to eat human flesh and strives for mutual aid and cooperation.

Gaddis also evokes the Hiawatha of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, itself a cannibalization of sorts of the mytho-historical Hiawatha. Gaddis grafts the oft-cited opening line of “Hiawatha’s Childhood,” “By the shores of Gitche Gumee” a few times early in the novel. The poem seems to loll and roll around in Oscar’s skull; as his alcoholic madness increases, the poem’s trochaic tetrameter infects his thoughts. The result is some of the most beautiful prose in the book (even if the lines are intended as half-parody). Consider the following passage, which begins with Oscar watching the sunset on the wetlands around his crumbling estate, takes flight into the poetic cannibalization of Longfellow’s lines, and winds up in the jumble of Oscar’s fish tank (I strongly suggest reading the passage aloud to hear the trochaic tetrameter):

Neither the red scream of sunset blazing on the icebound pond nor the thunderous purple of its risings on a landscape blown immense through leafless trees off toward the ocean where in flocks the wild goose Wawa, where Kahgahgee king of ravens with his band of black marauders, or where the Kayoshk, the seagulls, rose with clamour from their nests among the marshes and the Mama, the woodpecker seated high among the branches of the melancholy pine tree past the margins of the pond neither rose Ugudwash, the sunfish, nor the yellow perch the Sahwa like a sunbeam in the water banished here, with wind and wave, day and night and time itself from the domain of the discus by the daylight halide lamp, silent pump and power filter, temperature and pH balance and the system of aeration, fed on silverside and flake food, vitamins and krill and beef heart in a patent spinach mixture to restore their pep and lustre spitting black worms from the feeder when a crew of new arrivals (live delivery guaranteed, air freight collect at thirty dollars) brought a Chinese algae eater, khuli loach and male beta, two black mollies and four neons and a pair of black skirt tetra cruising through the new laid fronds of the Madagascar lace plant.

Forgive the long quote. Or don’t. As the novel swerves to its gloomy end, the poem overtakes Oscar’s consciousness, the transcendental beauty of Longfellow’s vision cannibalized by the chainsaws of “land developers,” the real fauna replaced with Disneyfied simulations to send him off to drunken troubled dream. Dreamy Oscar:

…made a bed with boughs of hemlock where the squirrel, Adjidaumo, from his ambush in the oak trees watched with eager eyes the lovers, watched him fucking Laughing Water and the rabbit, the Wabasso sat erect upon his haunches, watched him fucking Minnehaha as the birds sang loud and sweetly where the rumble of the trucks drowned the drumming of the pheasant and the heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah gave a cry of lamentation from her haunts among the fenlands at the howling of the chainsaws and the screams of the wood chipper for that showplace on the corner promising a whole new order of woodland friends for the treeless landscape, where Thumper the Rabbit and Flower the Skunk would introduce the simpering Bambi to his plundered environment and instruct him in matters of safety and convenience by the shining Big-Sea-Water, by the shores of Gitche Gumee where the desolate Nokomis drank her whisky at the fireside, not a word from Laughing Water left abandoned by the windows, from the wide eyed Ella Cinders with the mice her only playmates as he turned his back upon them with his birch canoe exulting, all alone went Hiawatha.

Many contemporary reviewers suggested that A Frolic of His Own was Gaddis’s most accessible novel to date, and it might be. Whereas J R and Carpenter’s Gothic are composed almost entirely in dialogue, Gaddis provides more stage direction and connective tissue in A Frolic. There are also the fragments of other forms: legal briefs, depositions, TV news clips, Oscar’s play…Some of these departures can exhaust a reader. Gaddis’s parodies of legalese are full of jokes, but the tone of the delivery can lead one’s mind’s eye to glaze over. Oscar/Gaddis’s play is problematic too, but in a rewarding if confounding way: Is it supposed to be, like, good? The answer, I think, comes in its cannibalized version—I mean the cannibalized version that Oscar watches over broadcast television. When he finally sees The Blood in the Red White and Blue, Oscar experiences a wild array of emotions, both positive and negative—but his feelings are real.

A Frolic of His Own is not the best starting point for anyone interested in William Gaddis’s fiction, although I don’t think that’s where most people start. It is rewarding though, especially read contextually against his other works, in which it fits chaotically but neatly, underscoring the cranky themes in a divergent style that still feels fresh three decades after its original publication. Highly recommended.

[Ed. note — Biblioklept first ran this review in June 2023. I’ve been falling asleep to William Hootkins’ reading of The Song of Hiawatha every night for the past two weeks.]

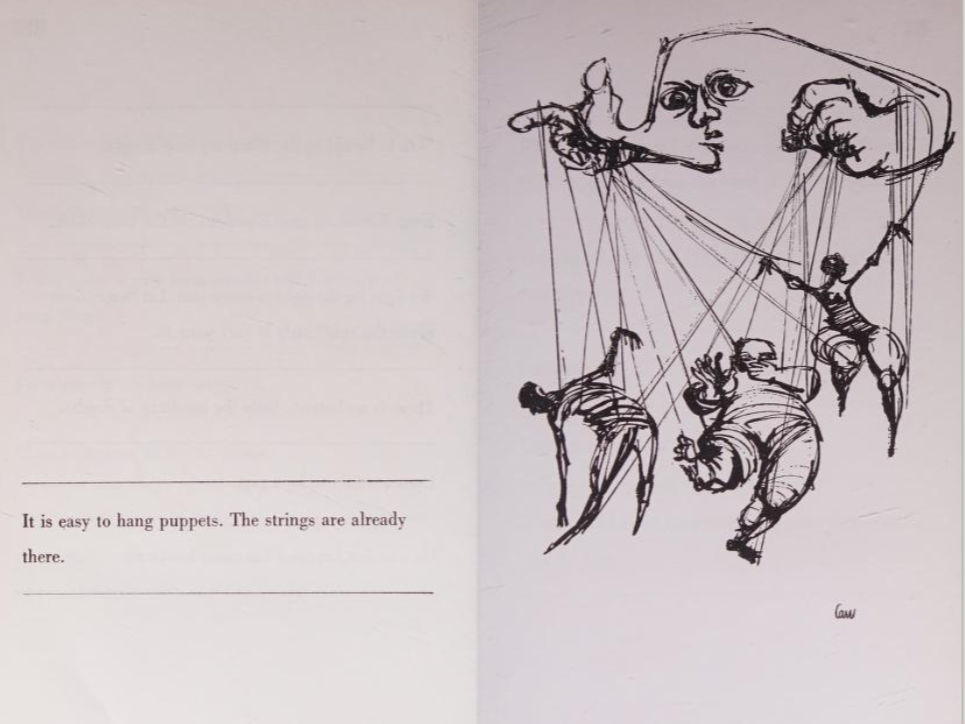

No One Writes to the Colonel and Other Stories, Gabriel García Márquez. Translation by J.S. Bernstein. Avon Bard (1973). No cover artist credited. 220 pages.

Another beautiful Avon Bard Latin American series cover that fails to attribute the cover artist. The “other” stories that supplement the titular novella are García Márquez’s 1962 collection Los funerales de la Mamá Grande. When I picked this up I fully expected the translator to be Gregory Rabassa, who did several of García Márquez’s major works, along with many, many of the other Avon Bard LA titles. But it’s J.S. Bernstein; as far as I can tell, this is their (his? her?) most famous translation. (Maybe Rabassa was doing a Richard Bachman thing.)

Continue reading “Mass-market Monday | Gabriel García Márquez’s No One Writes to the Colonel”

Reading, 1934 by Ishikawa Toraji (1875-1964)

Eco-Fiction, 1971, ed. John Stadler. Pocket Books (1971). No cover artist or designer credited. 206 pages.

The cover art is by Michael Eagle (you can see his signature in the illustration).

In addition to the names listed on the back cover, this collection also features stories by J.G. Ballard, Frank Herbert, J.F. Powers and more.

The vignette “The Turtle” condenses all of The Grapes of Wrath–and most of Steinbeck’s themes in general–into four paragraphs.

“The Turtle”

by

John Steinbeck

The concrete highway was edged with a mat of tangled, broken, dry grass, and the grass heads were heavy with oat beards to catch on a dog’s coat, and foxtails to tangle in a horse’s fetlocks, and clover burrs to fasten in sheep’s wool; sleeping life waiting to be spread and dispersed, every seed armed with an appliance of dispersal, twisting darts and parachutes for the wind, little spears and balls of tiny thorns, and all waiting for animals or the hem of a woman’s skirt, all passive but armed with appliances of activity, still, but each possessed of the anlage of movement.

The sun lay on the grass and warmed it, and in the shade under the grass the insects moved, ants and ant lions to set traps for them, grasshoppers to jump into the air and flick their yellow wings for a second, sow bugs like little armadillos, plodding restlessly on many tender feet. And over the grass at the roadside a land turtle crawled, turning aside for nothing, dragging his high-domed shell over the grass: His hard legs and yellow-nailed feet threshed slowly through the grass, not really walking, but boosting and dragging his shell along. The barley beards slid off his shell, and the clover burrs fell on him and rolled to the ground. His horny beak was partly opened, and his fierce, humorous eyes, under brows like fingernails, stared straight ahead. He came over the grass leaving a beaten trail behind him, and the hill, which was the highway embankment, reared up ahead of him. For a moment he stopped, his head held high. He blinked and looked up and down. At last he started to climb the embankment. Front clawed feet reached forward but did not touch. The hind feet kicked his shell along, and it scraped on the grass, and on the gravel. As the embankment grew steeper and steeper, the more frantic were the efforts of the land turtle. Pushing hind legs strained and slipped, boosting the shell along, and the horny head protruded as far as the neck could stretch. Little by little the shell slid up the embankment until at last a parapet cut straight across its line of march, the shoulder of the road, a concrete wall four inches high. As though they worked independently the hind legs pushed the shell against the wall. The head upraised and peered over the wall to the broad smooth plain of cement. Now the hands, braced on top of the wall, strained and lifted, and the shell came slowly up and rested its front end on the wall. For a moment the turtle rested. A red ant ran into the shell, into the soft skin inside the shell, and suddenly head and legs snapped in, and the armored tail clampled in sideways. The red ant was crushed between body and legs. And one head of wild oats was clamped into the shell by a front leg. For a long moment the turtle lay still, and then the neck crept out and the old humorous frowning eyes looked about and the legs and tail came out. The back legs went to work, straining like elephant legs, and the shell tipped to an angle so that the front legs could not reach the level cement plain. But higher and higher the hind legs boosted it, until at last the center of balance was reached, the front tipped down, the front legs scratched at the pavement, ad it was up. But the head of wild oats was held by its stem around the front legs.

Now the going was easy, and all the legs worked, and the shell boosted along, waggling from side to side. A sedan driven by a forty-year-old woman approached, She saw the turtle and swung to the right, off the highway, the wheels screamed and a cloud of dust boiled up. Two wheels lifted for a moment and then settled. The car skidded back onto the road, and went on, but more slowly. The turtle had jerked into its shell, but now it hurried on, for the highway was burning hot.

And now a light truck approached, and as it came near, the driver saw the turtle and swerved to hit it. His front wheel struck the edge of the shell, flipped the turtle like a tiddly-wink, spun it like a coin, and rolled it off the highway. The truck went back to its course along the right side. Lying on its back, the turtle was tight in its shell for a long time. But at last its legs waved in the air, reaching for something to pull it over. Its front foot caught a piece of quartz and little by little the shell pulled over and flopped upright. The wild oat head fell out and three of the spearhead seeds stuck in the ground. And as the turtle crawled on down the embankment, its shell dragged dirt over the seeds. The turtle entered a dust road and jerked itself along, drawing a wavy shallow trench in the dust with its shell. The old humorous eyes looked ahead, and the horny beak opened a little. His yellow toe nails slipped a fraction in the dust.

The Essential James Joyce, 1948, ed. Harry Levin. Penguin Books (1969). Cover art by Jacques Emile Blanche; photographed by John Freeman. 550 pages.

I found this book on the street in Shin-Kōenji, the neighborhood I lived in in Tokyo twenty-five years ago. It was, if I recall, stacked on top of a pile of pornographic manga. I may have taken those as well. Happy Bloomsday!

I can’t remember which particular Surrealist I was googling when I learned about Gisèle Prassinos. I do know that it was just a few weeks ago, and I’ve had an interest in Surrealist art and literature since I was a kid, so I was a bit stunned that I’d never heard of her before now—strange, given the origin of her first publication. In 1934, when she was 14, Prassinos was “discovered” by André Breton, and the Surrealists delighted in what they called her “automatic writing.” (Prassinos would later reject that label, and go as far as to declare that she had never been a surrealist). Her first book, La Sauterelle arthritique (The Arthritic Grasshopper) was published just a year later.

I somehow found a .pdf of one of her stories, “A Nice Family,” a bizarre little tale that runs on its own surreal mythology. The story struck me as simultaneously grandiose and miniature, dense but also skeletal. It was impossible. Surreal. I wanted more.

Luckily, just this spring Wakefield Press released The Arthritic Grasshopper: Collected Stories, 1934-1944, a new English translation of a 1976 compendium of Prassinos’s tales, Trouver sans checher. The translation is by Henry Vale and Bonnie Ruberg, whose introduction to the volume is a better review and overview than I can muster here. Ruberg offers a miniature biography, and shares details from her letters and visits with Prassinos. She situates Prassinos within the Surrealists’ gender biases: “For a young writer such as Prassinos, being involved with the surrealists would have meant gaining access to resources like publishers, but it also would have meant being fetishized and marginalized.” Ruberg characterizes Prassinos’s tales eloquently and accurately—no simple feat given the material’s utter strangeness:

Taken collectively, their effect is a piercing cackle, a complete disorientation, rather than an ethical lesson. The politics of these stories are absurdist. They upend the world by making children dangerous, by reanimating the dead, by letting the carefully tended domestic deform, foam, and melt. No social structure holds power in the world of these stories—not on the basis of gender, or nationality, or class. The force that reigns is chaos.

Let’s look at that reigning chaos.

In “The Sensitivity of Others,” one of the earliest tales in the volume, we get the sparest narrative action seemingly possible: A speaker walks forward. And yet dream-nightmare touches impinge on all sides and on all senses. The opening line shows a world that is never stable, and if monsters and other dangers lurk just on the margins of our narrator’s shifting path, so do wonders and the promise of strange knowledge. Here’s the tale in full:

I still have no idea what to make of the punchline there at the end, but those final images—a father, a faulty library, a power failure—hang heavy against the narrator’s trembling walk.

Many of Prassinos’s anti-fables conclude with such apparent non sequiturs, and yet the final lines can also cast a weird light back over the previous sentences. In “Photogenic Quality,” a dream-tale about the act of writing itself, the final line at first appears as sheer absurdity. A man receives a pencil from a child, whittles it into powder, blots the powder on paper, and throws the paper in the river (more things happen, too). The tale concludes with the man declaring, “Brass is made from copper and tin.” It’s possible to enjoy the absurdity here on its own; however, I think we can also read the last line as a kind of Abracadabra!, magic words that describe an almost alchemical synthesis—a synthesis much like the absurd modes of transformative writing that “Photogenic Quality” outlines.

You’ll see above one of Allan Kausch’s illustrations for The Arthritic Grasshopper. Kausch’s collages pointedly recall Max Ernst’s surreal 1934 graphic novel Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness). Kausch’s work walks a weird line between horror and whimsy; images from old children’s books and magazines become chimerical figures, sometimes cute, sometimes horrific, and sometimes both. They’re lovely.

Surreal figures shift throughout the book—monks and kings, daughters and mothers, deep sea divers and knights and salesmen and talking horses—all slightly out of place, or, rather, all making new places. Even when Prassinos establishes a traditional space we might think we recognize—often a fairy trope—she warps its contours, shaping it into something else. “A Marriage Proposal,” with its unsuspecting title, opens with “Once upon a time” — but we are soon dwelling in impossibility: “the garter snake appeared in the doorway, arm in arm with the snail, who was slobbering with happiness.” Other stories, like “Tragic Fanaticism,” immediately condense fairy tales into pure images, leaving the reader to suss out connections. Here is that story’s opening line: “A black hole, a little old woman, animals.” At five pages, “Tragic Fanaticism” is one of the collection’s longer stories. It ends with a four line poem, sung by five red cats to the old woman: “Go home and burn / Darling / You’re the only one we’ll love / Trash Bin.”

I still have a number of stories to read in The Arthritic Grasshopper. I’ve enjoyed its tales most when taken as intermezzos between sterner (or compulsory) reading. There’s something refreshing in Prassinos’s illogic. In longer stretches, I find that I tire, get lazy—Prassinos’s imagery shifts quickly—there’s something even picaresque to the stories—and keeping up with its veering rhythms for tale after tale can be taxing. Better not to gobble it all up at once. In this sense, The Arthritic Grasshopper reminds me strongly of another recently-published volume of surreal, imagistic stories that I’ve been slowly consuming this year: The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. In their finest moments, both of these writers can offer new ways of looking at art, at narrative, at the world itself.

I described Prassinos’s tales as “anti-fables” above—a description that I think is accurate enough, as literary descriptions go—but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something that we can learn from them (although, to be very clear, I do not think literature has to offer us anything to learn). What Prassinos’s anti-fables do best is open up strange impossible spaces—there’s a kind of radical, amorphous openness here, one that might be neatly expressed in the original title to this newly-translated volume—Trouver sans checher—To Find without Seeking.

In her preface (titled “To Find without Seeking”) Prassinos begins with the question, “To find what?” Here is a question that many of us have been taught we must direct to all the literature we read—to interrogate it so that it yields moral instruction. Prassinos answers: “The spot where innocence rejoices, trembling as it first meets fear. The spot where innocence unleashes its ferocity and its monsters.” She goes on to describe a “true and complete world” where the “earth and water have no borders and each us can live there if we choose, in just the same way, without changing our names.” Her preface concludes by repeating “To find what?”, and then answering the question in the most perfectly (im)possible way: “In the end, the mind that doesn’t know what it knows: the free astonishing voice that speaks, faceless, in the night.” Prassinos’s anti-fables offer ways of reading a mind that doesn’t know what it knows, of singing along with the free faceless astonishing voice. Highly recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally ran this review in August of 2017.]

Leonora Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet begins with its nonagenarian narrator forced into a retirement home and ends in an ecstatic post-apocalyptic utopia “peopled with cats, werewolves, bees and goats.” In between all sorts of wild stuff happens. There’s a scheming New Age cult, a failed assassination attempt, a hunger strike, bee glade rituals, a witches sabbath, an angelic birth, a quest for the Holy Grail, and more, more, more.

Composed in the 1950s and first published in 1974, The Hearing Trumpet is new in print again for the first time in nearly two decades from NYRB. NYRB also published Carrington’s hallucinatory memoir Down Below a few years back, around the same time as Dorothy issued The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. Most people first come to know Carrington through her stunning, surreal paintings, which have been much more accessible (because of the internet) than her literature. However, Dorothy’s Complete Stories brought new attention to Carrington’s writing, a revival continued in this new edition of The Hearing Trumpet.

Readers familiar with Carrington’s surreal short stories might be surprised at the straightforward realism in the opening pages of The Hearing Trumpet. Ninety-two-year-old narrator Marian Leatherby lives a quiet life with her son and daughter-in-law and her tee-vee-loving grandson. They are English expatriates living in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country, and although the weather is pleasant, Marian dreams of the cold, “of going to Lapland to be drawn in a vehicle by dogs, woolly dogs.” She’s quite hard of hearing, but her sight is fine, and she sports “a short grey beard which conventional people would find repulsive.” Conventional people will soon be pushed to the margins in The Hearing Trumpet.

Marian’s life changes when her friend Carmella presents her with a hearing trumpet, a device “encrusted with silver and mother o’pearl motives and grandly curved like a buffalo’s horn.” At Carmella’s prompting, Marian uses the trumpet to spy on her son and daughter-in-law. To her horror, she learns they plan to send her to an old folks home. It’s not so much that she’ll miss her family—she directs the same nonchalance to them that she affords to even the most surreal events of the novel—it’s more the idea that she’ll have to conform to someone else’s rules (and, even worse, she may have to take part in organized sports!).

The old folks home is actually much, much stranger than Marian could have anticipated:

First impressions are never very clear, I can only say there seemed to be several courtyards , cloisters , stagnant fountains, trees, shrubs, lawns. The main building was in fact a castle, surrounded by various pavilions with incongruous shapes. Pixielike dwellings shaped like toadstools, Swiss chalets , railway carriages , one or two ordinary bungalows, something shaped like a boot, another like what I took to be an outsize Egyptian mummy. It was all so very strange that I for once doubted the accuracy of my observation.

The home’s rituals and procedures are even stranger. It is not a home for the aged; rather, it is “The Institute,” a cult-like operation founded on the principles of Dr. and Mrs. Gambit, two ridiculous and cruel villains who would not be out of place in a Roald Dahl novel. Dr. Gambit (possibly a parodic pastiche of George Gurdjieff and John Harvey Kellogg) represents all the avarice and hypocrisy of the twentieth century. His speech is a satire of the self-important and inflated language of commerce posing as philosophy, full of capitalized ideals: “Our Teaching,” “Inner Christianity,” “Self Remembering” and so on. Ultimately, it’s Gambit’s constricting and limited patriarchal view of psyche and spirit that the events in The Hearing Trumpet lambastes.

Marian soon finds herself entangled in the minor politics and scheming of the Institute, even as she remains something of an outsider on account of her deafness. She’s mostly concerned with getting an extra morsel of cauliflower at mealtimes—the Gambits keep the women undernourished. She eats her food quickly during the communal dinner, and obsesses over the portrait of a winking nun opposite her seat at the table:

Really it was strange how often the leering abbess occupied my thoughts. I even gave her a name, keeping it strictly to myself. I called her Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva, a nice long name, Spanish style. She was abbess, I imagined, of a huge Baroque convent on a lonely and barren mountain in Castile. The convent was called El Convento de Santa Barbara de Tartarus, the bearded patroness of Limbo said to play with unbaptised children in this nether region.

Marian’s creative invention of a “Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva” soon somehow passes into historical reality. First, she receives a letter from her trickster-aid Carmella, who has dreamed about a nun in a tower. “The winking nun could be no other than Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva,” remarks Marian. “How very mysterious that Carmella should have seen her telepathically.” Later, Christabel, another member/prisoner of the Institute helps usher Marian’s fantasy into reality. She confirms that Marian’s name for the nun is indeed true (kinda sorta): “‘That was her name during the eighteenth century,’ said Christabel. ‘But she has many many other names. She also enjoys different nationalities.'”

Christabel gives Marian a book entitled A True and Faithful Rendering of the Life of Rosalinda Alvarez and the next thirty-or-so pages gives way to this narrative. This text-within-a-text smuggles in other texts, including a lengthy letter from a bishop, as well as several ancient scrolls. There are conspiracies afoot, schemes to keep the Holy Grail out of the hands of the feminine power the Abbess embodies. There are magic potions and an immortal bard. There is cross-dressing and a strange monstrous pregnancy. There are the Knights Templar.

Carrington’s prose style in these texts-within-texts diverges considerably from the even, wry calm of Marian’s narration. In particular, there’s a sly control to the bishop’s letter, which reveals a bit-too-keen interest in teenage boys. These matryoshka sections showcase Carrington’s rhetorical range while also advancing the confounding plot. They recall The Courier’s Tragedy, the play nested in Thomas Pynchon’s 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49. Both texts refer back to their metatexts, simultaneously explicating and confusing their audiences while advancing byzantine plot points and arcane themes.

Indeed, the tangled and surreal plot details of The Hearing Trumpet recall Pynchon’s oeuvre in general, but like Pynchon’s work, Carrington’s basic idea can be simplified to something like—Resistance to Them. Who is the Them? The patriarchy, the fascists, the killers. The liars, the cheaters, the ones who make war in the name of order. (One resister, the immortal traveling bard Taliesin, shows up in both the nested texts and later the metatext proper, where he arrives as a postman, recalling the Trystero of The Crying of Lot 49.)

The most overt voice of resistance is Marian’s best friend Carmella. Carmella initiates the novel by giving Marian the titular hearing trumpet, and she acts as a philosophical foil for her friend. Her constant warning that people under seventy and over seven should not be trusted becomes a refrain in the novel. Before Marian is shipped off to the Institution, Carmella already plans her escape, a scheme involving machine guns, rope, and other implements of adventure. Although she loves animals, Carmella is even willing to kill any police dogs that might guard the Institution and hamper their escape:

Police dogs are not properly speaking animals. Police dogs are perverted animals with no animal mentality. Policemen are not human beings so how can police dogs be animals?

Late in the novel, Carmella delivers perhaps the most straightforward thesis of The Hearing Trumpet:

It is impossible to understand how millions and millions of people all obey a sickly collection of gentlemen that call themselves ‘Government!’ The word, I expect, frightens people. It is a form of planetary hypnosis, and very unhealthy. Men are very difficult to understand… Let’s hope they all freeze to death. I am sure it would be very pleasant and healthy for human beings to have no authority whatever. They would have to think for themselves, instead of always being told what to do and think by advertisements, cinemas, policemen and parliaments.

Carmella’s dream of an anarchic utopia comes to pass.

How?

Well, there’s a lot to it, and I’d hate to spoil the surrealist fun. Let’s just say that Marian’s Grail quest scores a big apocalyptic win for the Goddess, thanks to “an army of bees, wolves, seven old women, a postman, a Chinaman, a poet, an atom-driven Ark, and a werewoman.” No conventional normies who might find Marian’s beard repulsive here.

With its conspiracy theories within conspiracy theories and Templar tales, The Hearing Trumpet will likely remind many readers of Umberto Eco’s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum (or one of its ripoffs). The Healing Trumpet’s surreal energy also recalls Angela Carter’s 1972 novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman. And of course, the highly-imagistic, ever-morphing language will recall Carrington’s own paintings, as well as those of her close friend Remedios Varo (who may have been the basis for Carmella), and their surrealist contemporaries (like Max Ernst) and forebears (like Hieronymus Bosch).

This new edition of The Hearing Trumpet includes an essay by the novelist Olga Tokarczuk (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones) which focuses on the novel as a feminist text. (Tokarczuk also mentions that she first read the novel without knowing who Carrington was). The new edition also includes black and white illustrations by Carrington’s son, Pablos Weisz Carrington (I’ve included a few in this review). As far as I can tell, these illustrations seem to be slightly different from the illustrations included in the 2004 edition of The Hearing Trumpet published by Exact Change. That 2004 edition has been out of print for ages and is somewhat hard (or really, expensive) to come by (I found a battered copy few years ago for forty bucks). NYRB’s new edition should reach the wider audience Carrington deserves.

Some readers will find the pacing of The Hearing Trumpet overwhelming, too frenetic. It moves like a snowball, gathering images, symbols, motifs into itself in an ever-growing, ever-speeding mass. Other readers may have difficulty with its ever-shifting plot. Nothing is stable in The Hearing Trumpet; everything is liable to mutate, morph, and transform. Those are my favorite kinds of novels though, and I loved The Hearing Trumpet—in particular, I loved its tone set against its imagery and plot. Marian’s narration is straightforward, occasionally wry, but hardly ever astonished or perplexed by the magical and wondrous events she takes part in. There’s a lot I likely missed in The Hearing Trouble—Carrington lards the novel with arcana, Jungian psychology, magical totems, and more more more—but I’m sure I’ll find more the next time I read it. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept first ran this review in December, 2020.]

Ann Quin’s third novel Passages (1969) ostensibly tells the story of an unnamed woman and unnamed man traveling through an unnamed country in search of the woman’s brother, who may or may not be dead.

The adverb ostensibly is necessary in the previous sentence, because Passages does not actually tell that story—or it rather tells that story only glancingly, obliquely, and incompletely. Nevertheless, that is the apparent “plot” of Passages.

Quin is more interested in fractured/fracturing voices here. Passages pushes against the strictures of the traditional novel, eschewing character and plot development in favor of pure (and polluted) perceptions. There’s something schizophrenic about the voices in Passages. Interior monologues turn polyglossic or implode into elliptical fragments.

Quin repeatedly refuses to let her readers know where they stand. Indeed, we’re never quite sure of even the novel’s setting, which seems to be somewhere in the Mediterranean. It’s full of light and sea and sand and poverty, and the “political situation” is grim. (The woman’s brother’s disappearance may or may not have something to do with the region’s political instability.)

Passage’s content might be too slippery to stick to any traditional frame, but Quin employs a rhetorical conceit that teaches her reader how to read her novel. The book breaks into four unnamed chapters, each around twenty-five pages long. The first and third chapters find us loose in the woman’s stream of consciousness. The second and fourth chapters take the form of the man’s personal journal. These sections contain marginal annotations, which might be meant to represent actual physical annotations, or perhaps mental annotations–the man’s stream of consciousness while he rereads his journal.

Quin’s rhetorical strategy pays off, particularly in the book’s Sadean climax. This (literal) climax occurs at a carnivalesque party in a strange mansion on a small island. We see the events first through the woman’s perception, and then through the man’s. But I’ve gone too long without offering any representative language. Here’s a passage from the woman’s section, just a few paragraphs before the climax. To set the stage a bit, simply know that the woman plays voyeur to a bizarre threesome:

Mirrors faced each other. As the two turned, approached. Slower in movement in the centre, either side of him, turning back in the opposite direction to their first movement. Contours of their shadows indistinct. The first mirror reflected in the second. The second in the first. Images within images. Smaller than the last, one inside the other. She lay on the floor, wrists tied together. She bent back over the chair. He raised the whip, flung into space.

Later, the man’s perception of events at the party both clarify and cloud the woman’s account. As you can see in the excerpt above, the woman frequently refuses to qualify her pronouns in a way that might stabilize identities for her reader. Such obfuscation often happens in the course of a sentence or two:

I ran on, knowing I was being followed. She came to the edge, jumped into expanding blueness, ultra violet tilted as she went towards the beach. We walked in silence.

The woman’s I becomes a She and then merges into a We. The other half of that We is a He, the follower (“He later threw the bottle against the rocks”), but we soon realize that this He is not the male protagonist, but simply another He that the woman has taken as a one-time lover.

The woman frequently takes off somewhere to have sex with another man. At times the sex seems to be part of her quest to find her brother; other times it’s simply part of the novel’s dark, erotic tone. The man is undisturbed by his lover’s faithlessness. He is passive, depressive, and analytical, while she is manic and exuberant. Late in the novel he analyzes himself:

How many hours I waste lying in bed thinking about getting up. I see myself get up, go out, move, drink, eat, smile, turn, pay attention, talk, go up, go down. I am absent from that part, yet participating at the same time. A voyeur in all senses, in my actions, non-actions. What a delight it might be actually to get up without thinking, and then when dressed look back and still see myself curled up fast asleep under the blankets.

The man longs for a kind of split persona, an active agent to walk the world who can also gaze back at himself dormant, passive.

This motif of perception and observation echoes throughout Passages. Consider one of the man’s journal entries from early in the book:

Above, I used an image instead of text to give a sense of what the journal entries and their annotations look like. Here, the man’s annotation is a form of self-observation, self-analysis.

Other annotations dwell on describing myths or artifacts (often Greek or Talmudic). In a “December” entry, the man’s annotation is far lengthier than the text proper. The main entry reads:

I am on the verge of discovering my own demoniac possibilities and because of this I am conscious I am not alone with myself.

Again, we see the fracturing of identity, consciousness as ceaseless self-perception. The annotation is far more colorful in contrast:

An ancient tribe of the Kouretes were sorcerers and magicians. They invented statuary and discovered metals, and they were amphibious and of strange varieties of shape, some like demons, some like men, some like fishes, some like serpents, and some had no hands, some no feet, some had webs between their fingers like gees. They were blue-eyed and black-tailed. They perished struck down by the thunder of Zeus or by the arrows of Apollo.

Quin’s annotations dare her reader to make meaning—to put the fragments together in a way that might satisfy the traditional expectations we bring to a novel. But the meaning is always deferred, always slips away. Passages collapses notions of center and margin. As its title suggests, this is a novel about liminal people, liminal places.

The results are wonderfully frustrating. Passages is abject, even lurid at times, but also rich and even dazzling in moments, particularly in the woman’s chapters, which read like pure perception, untethered by traditional narrative expectations like causation, sequence, and chronology.

As such, Passages will not be every reader’s cup of tea. It lacks the sharp, grotesque humor of Quin’s first novel, Berg, and seems dead set at every angle to confound and even depress its readers. And yet there’s a wild possibility in Passages. In her introduction to the new edition of Passages recently published by And Other Stories, Claire-Louise Bennett tries to capture the feeling of reading Quin’s novel:

It’s difficult to describe — it’s almost like the omnipotent curiosity one burns with as an adolescent — sexual, solipsistic, melancholic, fierce, hungry, languorous — and without limit.

Bennett, whose anti-novel Pond bears the stamp of Quin’s influence, employs the right adjectives here. We could also add disorienting, challenging, abject and even distressing. While clearly influenced by Joyce and Beckett, Quin’s writing in Passages seems closer to William Burroughs’s ventriloquism and the hollowed-out alienation of Anna Kavan’s early work. Passages also points towards the writing of Kathy Acker, Alasdair Gray, and João Gilberto Noll, among others. But it’s ultimately its own weird thing, and half a century after its initial publication it still seems ahead of its time. Passages is clearly Not For Everyone but I loved it. Recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally posted this review in May 2021.]

Dinah Brooke’s 1973 novel Lord Jim at Home had been out of print for five decades — and had never gotten a U.S. release — until McNally Editions republished in 2023 with a new foreword by the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh. I always save forewords until after I’ve finished a novel, so I missed Moshfegh’s implicit advice to go into Lord Jim at Home cold. She notes that the recommendation she received to read it “came with no introduction,” and that “I wouldn’t have wanted the effect of the novel to be mitigated in any way, so I’m reluctant to introduce it now.”

I am not reluctant to write about Brooke’s novel because I am so enthusiastic about it and I think those with tastes in literature similar to my own will find something fascinating in its plot and prose. However, l agree with Moshfegh’s advice that Lord Jim at Home is best experienced free from as much mitigating context as possible. I had never heard of the novel before lifting it from a bookseller’s shelf, attracted by the striking cover; I flipped it over to read a blurb parsed from Moshfegh’s foreword attesting that Brooke’s novel “was an instrument of torture. It’s that good.” The inside flap informed me that reviews upon its publication “described it as ‘squalid and startling,’ ‘nastily horrific,’ and a ‘monstrous parody’ of upper-middle class English life.” I was sold.

Lord Jim at Home is squalid and startling and nastily horrific. It is abject, lurid, violent, and dark. It is also sad, absurd, mythic, often very funny, and somehow very, very real for all its strangeness. The novels I would most liken Lord Jim at Home to, at least in terms of the aesthetic and emotional experience of reading it, are Ann Quin’s Berg, Anna Kavan’s Ice, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and James Joyce’s Portrait (as well as bits of Ulysses). (I have not read Conrad’s Lord Jim, which Brooke has taken as something of a precursor text for Lord Jim at Home.)

After finishing Lord Jim at Home, I read it again by accident. At first I intended to take a few notes for a possible review, but after the first few pages I just kept reading. On a second reading, Brooke’s novel was just as strange—maybe even stranger—even if I was able to read it much more quickly, finding myself quicker to tune into the novel’s competing (and complementary) narrative registers. I found it far more precise, too, in the rhetorical development of its themes; Brooke’s styles and tones shift to capture the different ages of its hero. The novel begins in a mythical, archetypal mode and works its way through various registers, exploring the tropes of schoolboy novels, romances, war stories, adventure tales, modernism, realism, and journalism. But despite its shifting modes, Lord Jim at Home is not a parodic pastiche. Rather, at its core, Lord Jim at Home skewers how aesthetic modes—primarily those derived from notions of class and manners—cover over abject cruelty. As Moshfegh puts it in her forward, Lord Jim at Home is “an accurate portrayal of how fucked-up people behave, artfully conveyed in a way that nice people are too polite to admit they understand.”

I’ve tried to be clear that I think it’s best to come to Lord Jim at Home without too much context—it’s best to just go with the novel’s strangeness. Below, however, I offer a more detailed discussion of the novel, its language, and some elements of the plot for those so inclined.

Continue reading “A review of Dinah Brooke’s excellent cult novel Lord Jim at Home”

“Titian Paints a Sick Man”

by

Roberto Bolaño

translated by Natasha Wimmer

At the Uffizi, in Florence, is this odd painting by Titian. For a while, no one knew who the artist was. First the work was attributed to Leonardo and then to Sebastiano del Piombo. Though there’s still no absolute proof, today the critics are inclined to credit it to Titian. In the painting we see a man, still young, with long dark curly hair and a beard and mustache perhaps slightly tinged with red, who, as he poses, gazes off toward the right, probably toward a window that we can’t see, but still a window that somehow one imagines is closed, yet with curtains open or parted enough to allow a yellow light to filter into the room, a light that in time will become indistinguishable from the varnish on the painting.

The young man’s face is beautiful and deeply thoughtful. He’s looking toward the window, if he’s looking anywhere, though probably all he sees is what’s happening inside his head. But he’s not contemplating escape. Perhaps Titian told him to turn like that, to turn his face into the light, and the young man is simply obeying him. At the same time, one might say that all the time in the world stretches out before him. By this I don’t mean that the young man thinks he’s immortal. On the contrary. The young man knows that life renews itself and that the art of renewal is often death. Intelligence is visible in his face and his eyes, and his lips are turned down in an expression of sadness, or maybe it’s something else, maybe apathy, none of which excludes the possibility that at some point he might feel himself to be master of all the time in the world, because true as it is that man is a creature of time, theoretically (or artistically, if I can put it that way) time is also a creature of man.

In fact, in this painting, time — sketched in invisible strokes — is a kitten perched on the young man’s hands, his gloved hands, or rather his gloved right hand which rests on a book: and this right hand is the perfect measure of the sick man, more than his coat with a fur collar, more than his loose shirt, perhaps of silk, more than his pose for the painter and for posterity (or fragile memory), which the book promises or sells. I don’t know where his left hand is.

How would a medieval painter have painted this sick man? How would a non-figurative artist of the twentieth century have painted this sick man? Probably howling or wailing in fear. Judged under the eye of an incomprehensible God or trapped in the labyrinth of an incomprehensible society. But Titian gives him to us, the spectators of the future, clothed in the garb of compassion and understanding. That young man might be God or he might be me. The laughter of a few drunks might be my laughter or my poem. That sweet Virgin is my friend. That sad-faced Virgin is the long march of my people. The boy who runs with his eyes closed through a lonely garden is us.

Memento Mori, 1954, Muriel Spark. Avon Bard (1978). No cover artist or designer credited. 191 pages.

From David Lodge’s 2010 reappraisal of the novel in The Guardian:

The fiction of the 50s was dominated by a new wave of social realism, represented by novels such as Lucky Jim, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and Room at the Top, whose originality lay in tone and attitude rather than technique. Typically they were narrated in the first person or in free indirect style, articulating the consciousness of a single character, usually a young man, whose rather ordinary but well observed life revealed new tensions and fault-lines in postwar British society. An unsympathetic character in Memento Mori called Eric has evidently written two dispiriting works of this kind. Memento Mori itself was an utterly different and virtually unprecedented kind of novel. It is a short book, but it has a huge cast of characters, to nearly all of whose minds the reader is given access. The speed and abruptness with which the narrative switches from one point of view to another, managed and commented on by an impersonal but intrusive narrator, is a distinguishing feature of nearly all Spark’s fiction, and it violated the aesthetic rules not only of the neorealist novel, but also of the modernist novel from Henry James to Virginia Woolf. Spark was a postmodernist writer before that term was known to literary criticism. She took the convention of the omniscient author familiar in classic 19th-century novels and applied it in a new, speeded-up, throwaway style to a complex plot of a kind excluded from modern literary fiction – in this case involving blackmail and intrigues over wills, multiple deaths and discoveries of secret scandals, almost a parodic update of a Victorian sensation novel. And she added to the mix an element of the uncanny, through which the existence of a transcendent, eternal and immaterial reality impinges on the lives of her ageing characters, reminding them of their mortality.

Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick is probably my favorite book.

***

Years ago at an awful dinner party a man I didn’t know asked me What do you do?, by which he meant how I made money to live, or, maybe charitably, if I had a specific profession. When I told him it had something to do with literature and college students he followed up with a question no stranger should aim at another stranger-

-So what’s your favorite book then?

-Moby-Dick is my favorite book, I offered, this being my somewhat standard answer then.

-Oh no, I mean, what’s your real favorite book—not just the one you say to impress people?

–Okay Gravity’s Rainbow is my favorite book.

-I haven’t read that one yet but I like Tom Clancy too.

***

A dear friend at our house this weekend, under truly awful circumstances, circumstances that have no bearing on this riff, claimed to have counted “eighteen copies” of Moby-Dick around the house. As far as I could tell, there are only about thirteen, including a children’s pop up version and three comic book adaptations (I don’t know how he would’ve found the comic adaptations, as they are slim and I think in drawer or box). He asked for one; I offered him the UC Press edition illustrated by Barry Moser, the one I’d used the last time I reread Moby-Dick. He opted instead for the most recent Norton Critical Edition, which a rep sent me a few years ago.

***

The last time I reread Moby-Dick I used the UC Press edition illustrated by Barry Moser. This was in 2021. I ended up writing forty riffs on the novel, likely trying the patience of any regular readers of this blog.

***

If you’re not up for forty riffs, I wrote a very short riff on this very long book back in 2013.

***

The two preceding notes are my way of saying: Moby-Dick is probably my favorite novel; it’s fantastic and I’ve written about it in both short and long form, and I think anyone can read it and should–it’s funny, sad, thrilling, captivating, meditative, beguiling, baffling–a thing larger than its own frame, certainly larger than its author and his era. And so now–

***

I have another Moby-Dick. This one is designed and illustrated by Dmitry Samarov. It’s about 650 pages, and is a pleasing, squarish shape that rests easy in the hands (a contrast to the coffin-shaped Norton Critical Editions). The pages are not too bright (I hate bright white pages) nor too crisp; the spine is not so rigid that one seeks to break it before setting about the business of checking into the Spouter Inn. It is a very readable copy — relaxed, not too heavy and not too cramped, no precious footnotes. And there are Samarov’s sketches.

***

***

Rifling (or is it riffling? I can never remember) through this edition today, reading a few passages aloud even, just to feel myself go a little crazy and then get a small relief from that craze, the dominant sense I got from Samarov’s accompanying sketches is something like this: Someone riffing along to Ishmael’s ghost-voice, not competing with it nor trying to turn the mechanics of its verbs and nouns and adjectives into a mimetic representation of action or thought. I think the drawings, as a body, rather approximate something like an aesthetic ear tuned to Ishmael’s wail: scratchy ink lines tangle into and out of shapes in a discourse with the narrative. Others tuned to the voice might on any given page jot down a note or circle a phrase or even, dare, dream of a crowded footnote; Samarov offers a sketch. His love for the novel comes through.

***

If you haven’t read Moby-Dick, you should. Samarov’s edition is a worthy entry into the fold. Check it out.

“The Meaning of Mourning”

by

Sabine Baring-Gould

from Curiousities of Olden Times, 1896

A strip of black cloth an inch and a half in width stitched round the sleeve—that is the final, or perhaps penultimate expression (for it may dwindle further to a black thread) of the usage of wearing mourning on the decease of a relative.

The usage is one that commends itself to us as an outward and visible sign of the inward sentiment of bereavement, and not one in ten thousand who adopt mourning has any idea that it ever possessed a signification of another sort. And yet the correlations of general custom—of mourning fashions, lead us to the inexorable conclusion that in its inception the practice had quite a different signification from that now attributed to it, nay more, that it is solely because its primitive meaning has been absolutely forgotten, and an entirely novel significance given to it, that mourning is still employed after a death.

Look back through the telescope of anthropology at our primitive ancestors in their naked savagery, and we see them daub themselves with soot mingled with tallow. When the savage assumed clothes and became a civilised man, he replaced the fat and lampblack with black cloth, and this black cloth has descended to us in the nineteenth century as the customary and intelligible trappings of woe.

The Chinaman when in a condition of bereavement assumes white garments, and we may be pretty certain that his barbarous ancestor, like the Andaman Islander of the present day, pipeclayed his naked body after the decease and funeral of a relative. In Egypt yellow was the symbol of sorrow for a death, and that points back to the ancestral nude Egyptian having smeared himself with yellow ochre.

Black was not the universal hue of mourning in Europe. In Castile white obtained on the death of its princes. Herrera states that the last time white was thus employed was in 1498, on the death of Prince John. This use of white in Castile indicates chalk or pipeclay as the daub affected by the ancestors of the house of Castile in primeval time as a badge of bereavement. Continue reading ““The Meaning of Mourning” – – Sabine Baring-Gould”

Sadness, 1972, Donald Barthelme. Kangaroo Pocket Books (1980). No cover artist or designer credited. 159 pages.

Here is the fifth section of “Departures,” a series of vignettes. It stands alone as its own short story–

My grandfather once fell in love with a dryad—a wood nymph who lives in trees and to whom trees are sacred and who dances around trees clad in fine leaf-green tutu and who carries a great silver-shining axe to whack anybody who does any kind of thing inimical to the well-being and mental health of trees. My grandfather was at that time in the lumber business.

It was during the Great War. He’d got an order for a million board feet of one-by-ten of the very poorest quality, to make barracks out of for the soldiers. The specifications called for the dark red sap to be running off it in buckets and for the warp on it to be like the tops of waves in a distressed sea and for the knotholes in it to be the size of an intelligent man’s head for the cold wind to whistle through and toughen up the (as they were then called) doughboys.

My grandfather headed for East Texas. He had the timber rights to ten thousand acres there, Southern yellow pine of the loblolly family. It was third-growth scrub and slash and shoddy—just the thing for soldiers. Couldn’t be beat. So he and his men set up operations and first crack out of the box they were surrounded by threescore of lovely dryads and hamadryads all clad in fine leaf-green tutus and waving great silver-shining axes.

“Well now,” my grandfather said to the head dryad, “wait a while, wait a while, somebody could get hurt.”

“That is for sure,” says the girl, and she shifts her axe from her left hand to her right hand.

“I thought you dryads were indigenous to oak,” says my grandfather, “this here is pine.”

“Some like the ancient tall-standing many-branched oak,” says the girl, “and some the white-slim birch, and some take what they can get, and you will look mighty funny without any legs on you.”

“Can we negotiate,” says my grandfather, “it’s for the War, and you are the loveliest thing I ever did see, and what is your name?”

“Megwind,” says the girl, “and also Sophie. I am Sophie in the night and Megwind in the day and I make fine whistling axe-music night or day and without legs for walking your life’s journey will be a pitiable one.”

“Well Sophie,” says my grandfather, “let us sit down under this tree here and open a bottle of this fine rotgut here and talk the thing over like reasonable human beings.”

“Do not use my night-name in the light of day,” says the girl, “and I am not a human being and there is nothing to talk over and what type of rotgut is it that you have there?”

“It is Teamster’s Early Grave,” says my grandfather, “and you’ll cover many a mile before you find the beat of it.”

“I will have one cupful,” says the girl, “and my sisters will have each one cupful, and then we will dance around this tree while you still have legs for dancing and then you will go away and your men also.”

“Drink up,” says my grandfather, “and know that of all the women I have interfered with in my time you are the absolute top woman.”

“I am not a woman,” says Megwind, “I am a spirit, although the form of the thing is misleading I will admit.”

“Wait a while,” says my grandfather, “you mean that no type of mutual interference between us of a physical nature is possible?”

“That is a thing I could do,” says the girl, “if I chose.”

“Do you choose?” asks my grandfather, “and have another wallop.”

“That is a thing I will do,” says the girl, and she had another wallop.

“And a kiss,” says my grandfather, “would that be possible do you think?”

“That is a thing I could do,” says the dryad, “you are not the least prepossessing of men and men have been scarce in these parts in these years, the trees being as you see mostly scrub, slash and shoddy.”

“Megwind,” says my grandfather, “you are beautiful.”

“You are taken with my form which I admit is beautiful,” says the girl, “but know that this form you see is not necessary but contingent, sometimes I am a fine brown-speckled egg and sometimes I am an escape of steam from a hole in the ground and sometimes I am an armadillo.”

“That is amazing,” says my grandfather, “a shape-shifter are you.”

“That is a thing I can do,” says Megwind, “if I choose.”

“Tell me,” says my grandfather, “could you change yourself into one million board feet of one-by-ten of the very poorest quality neatly stacked in railroad cars on a siding outside of Fort Riley, Kansas?”

“That is a thing I could do,” says the girl, “but I do not see the beauty of it.”

“The beauty of it,” says my grandfather, “is two cents a board foot.”

“What is the quid pro quo?” asks the girl.

“You mean spirits engage in haggle?” asks my grandfather.

“Nothing from nothing, nothing for nothing, that is a law of life,” says the girl.

“The quid pro quo,” says my grandfather, “is that me and my men will leave this here scrub, slash and shoddy standing. All you have to do is to be made into barracks for the soldiers and after the War you will be torn down and can fly away home.”

“Agreed,” says the dryad, “but what about this interference of a physical nature you mentioned earlier? for the sun is falling down and soon I will be Sophie and human men have been scarce in these parts for ever so damn long.”

“Sophie,” says my grandfather, “you are as lovely as light and let me just fetch another bottle from the truck and I will be at your service.”

This is not really how it went. I am fantasizing. Actually, he just plain cut down the trees.

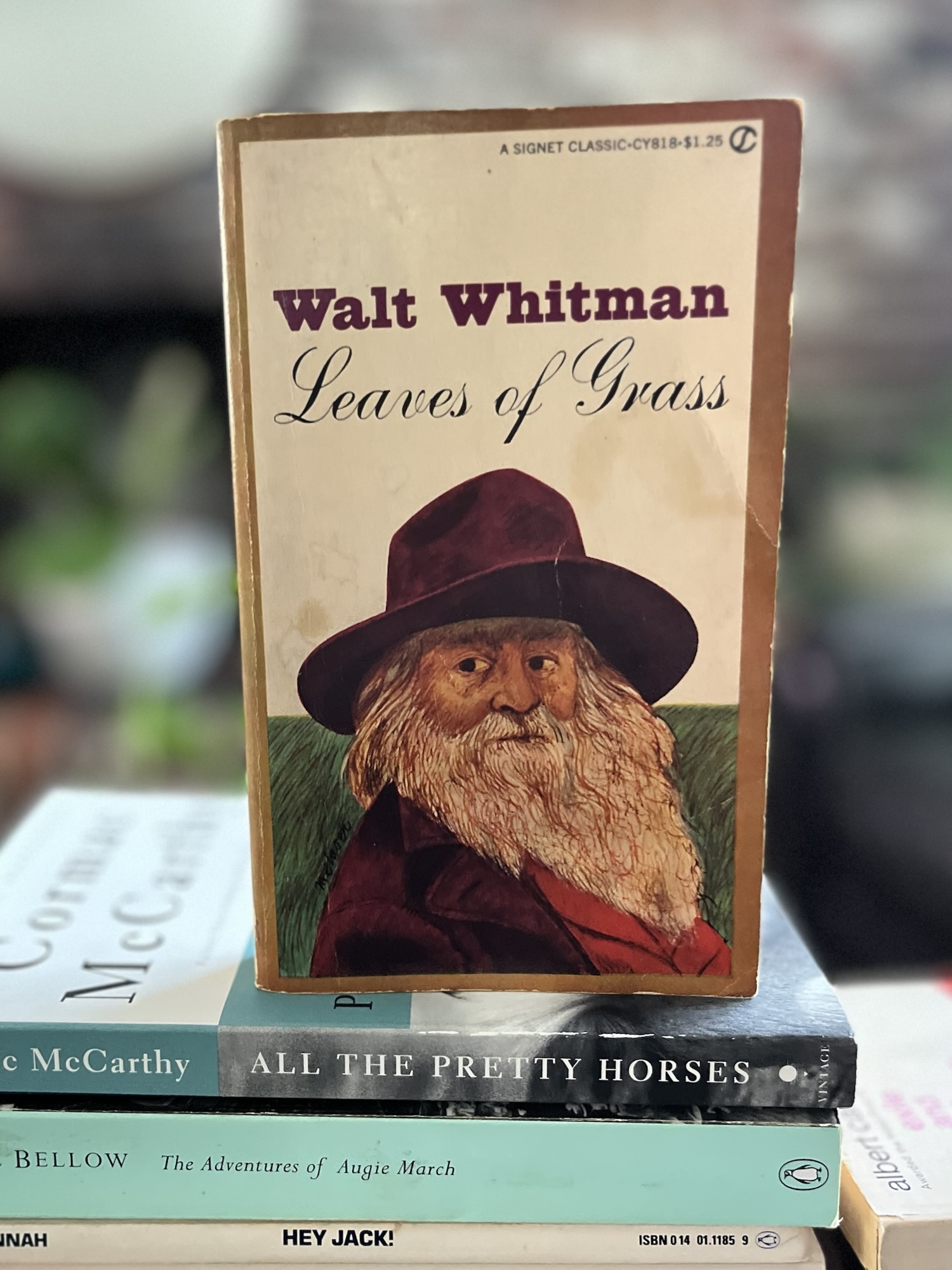

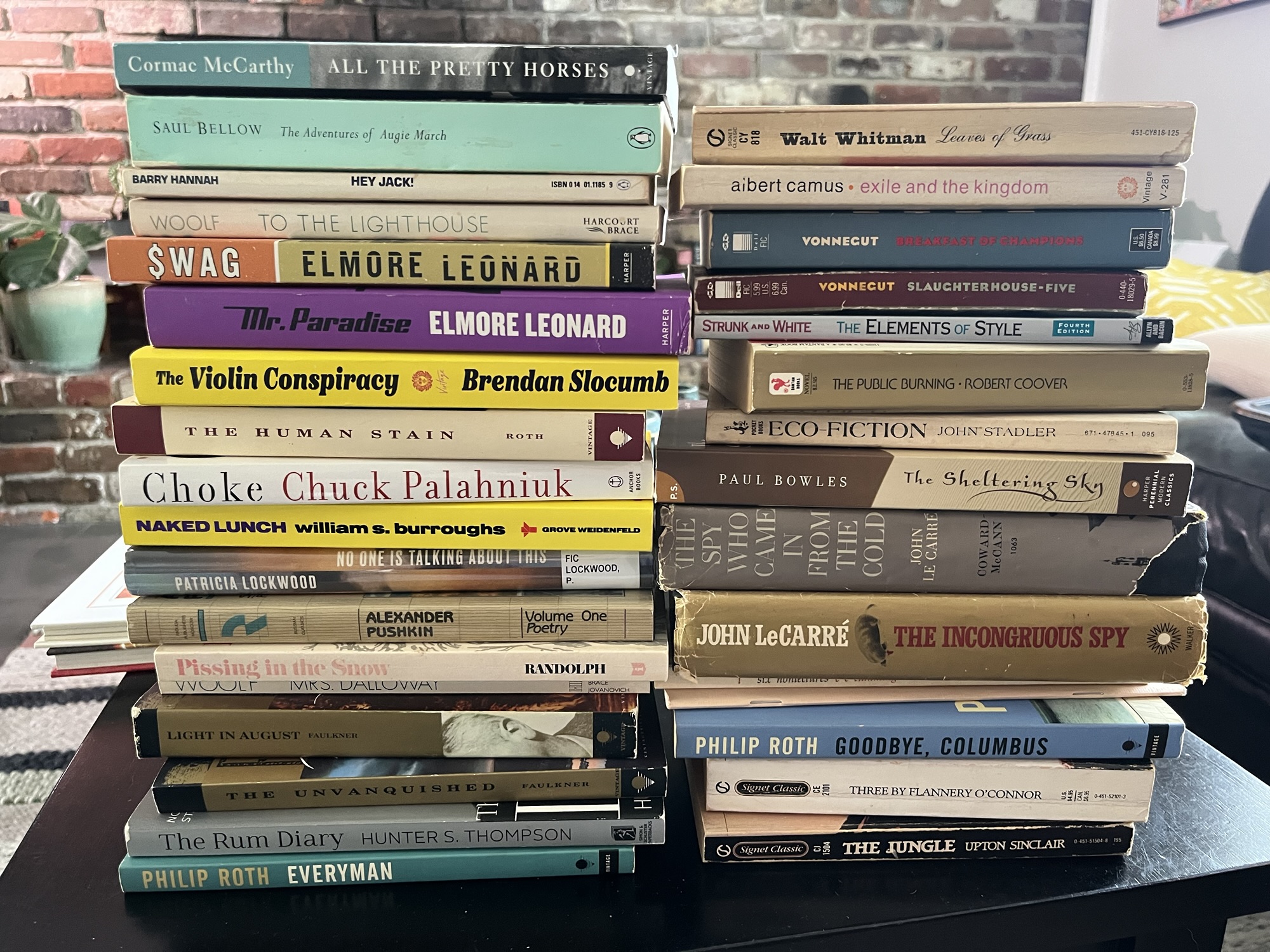

My move over the last few years when I go to a Friends of the Library Sale is to fill the ten dollar paper bag with a handful of pristine trade paperbacks I think will recoup the ten bucks in trade at my local used bookstore. I then pick through for titles to bolster my children’s growing personal libraries and for books that I might want to give away to friends, family, and students. And maybe I might get lucky with some overlooked gem — a first edition, a rarity, an oddity.

Most of what I picked up today was for my son to pick through. He took the Camus, Vonnegut, O’Connor, Palahniuk, and McCarthy. My daughter had zero interest in any of the haul.

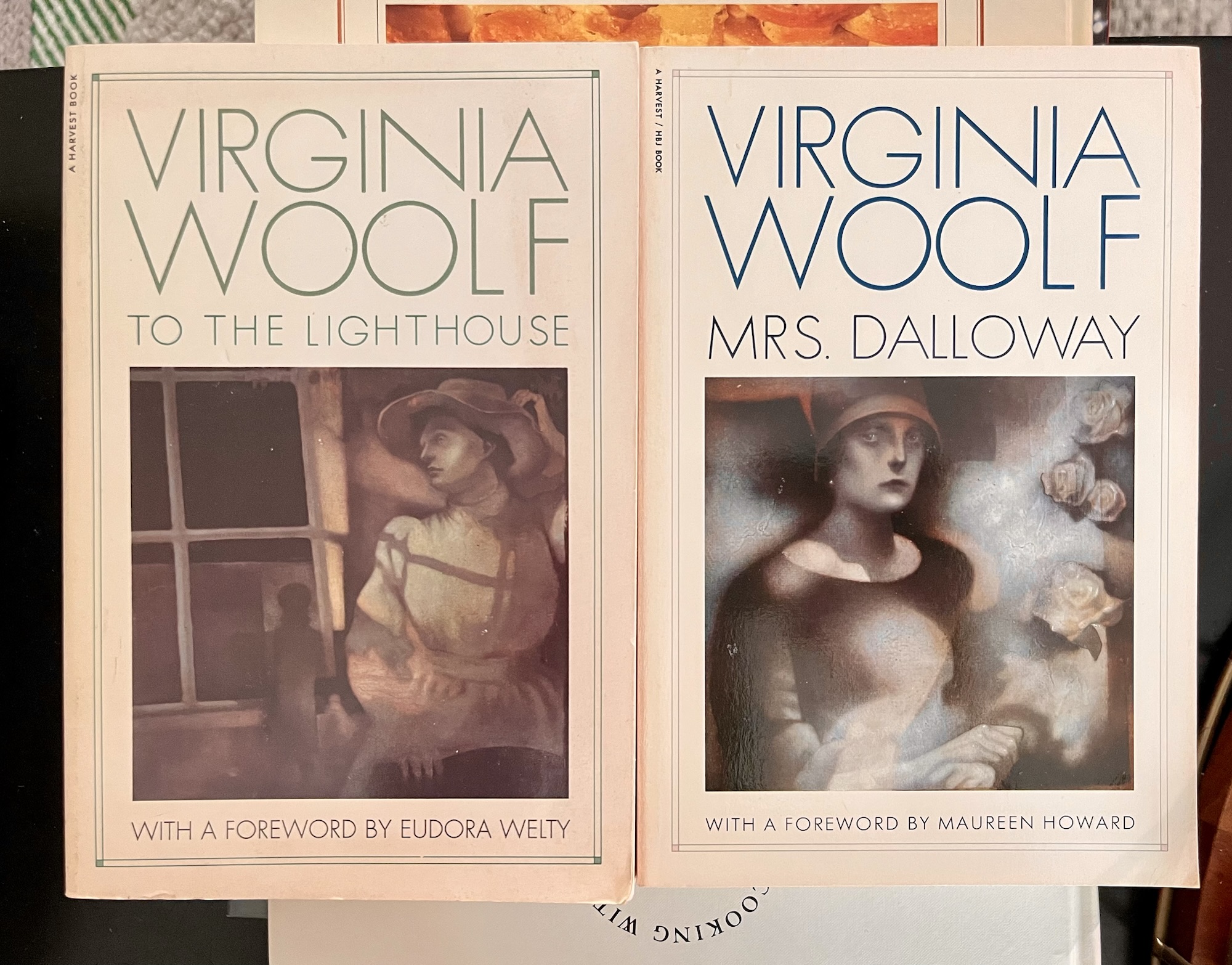

I wound up with several of the exact same editions of titles I already own (Camus’ Exile and Kingdom; Faulkner’s A Light in August; William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch) and lots of books we already have in other editions, most of which I’ll give away or trade. But I’ll be happy to trade out the cheap mass markets of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse I’ve had forever in favor of these HBJ Woolfs (Wolves?):

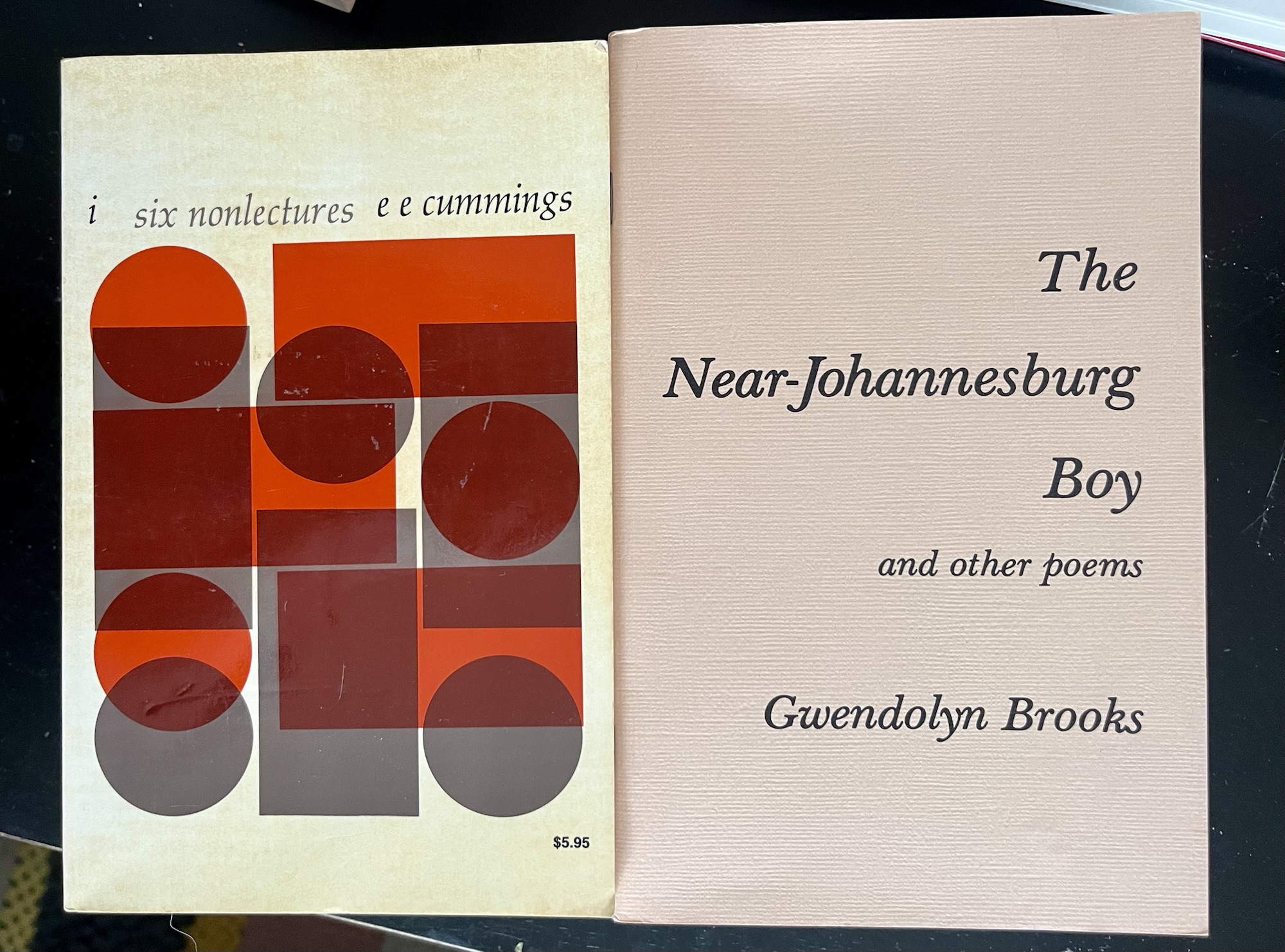

My two favorite finds today were cummings’ six nonlectures (the midcentury cover is lovely) and a Gwendolyn Brooks chapbook, The Near-Johannesburg Boy:

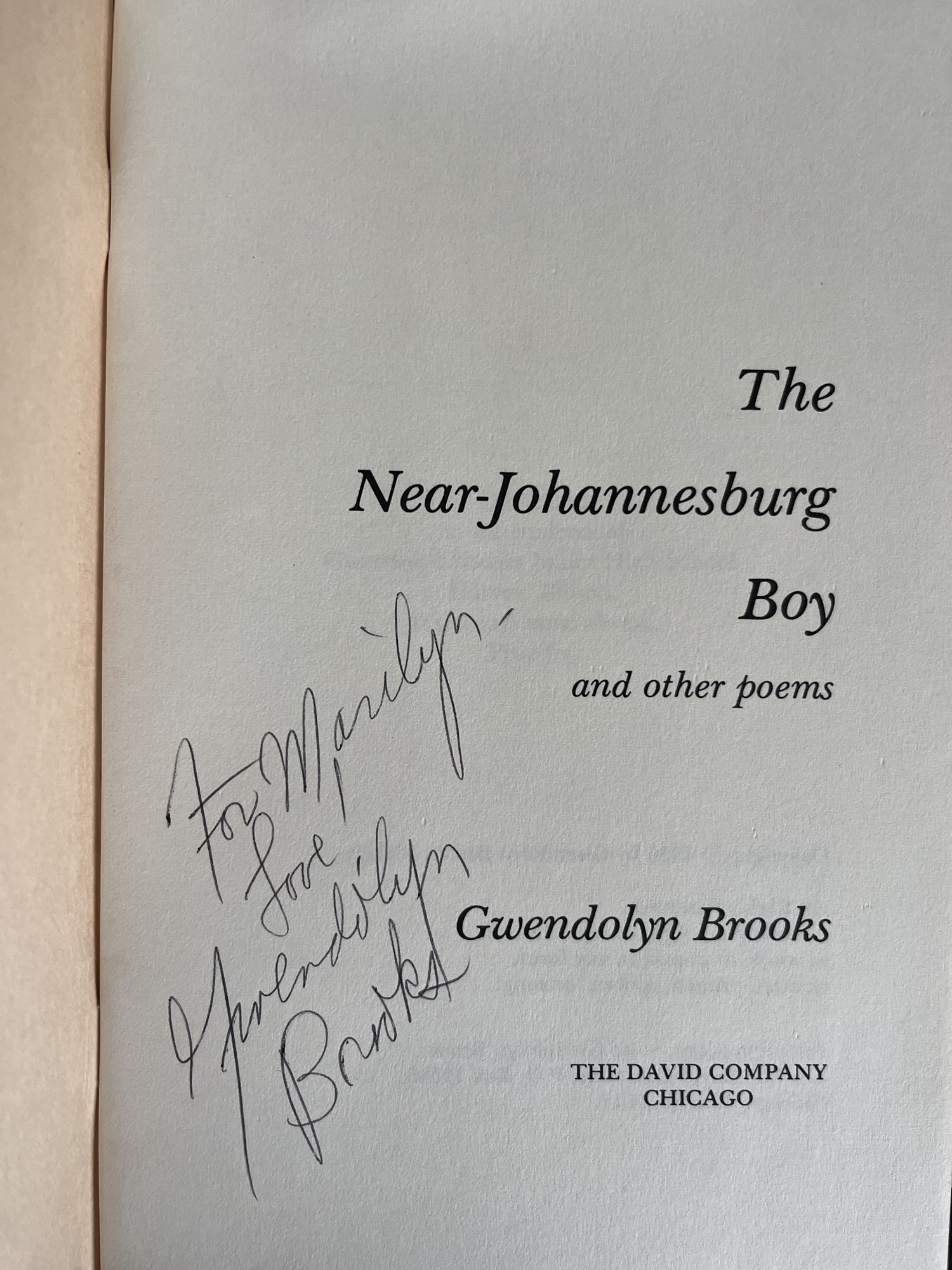

It wasn’t until I got home that I realized the Brooks’ chapbook was signed:

I had actually found two signed Brooks’ books at my favorite local used shop, also both inscribed to “Marilyn” (one was Blacks; I can’t remember the other one; they were both priced a bit beyond my casual range).

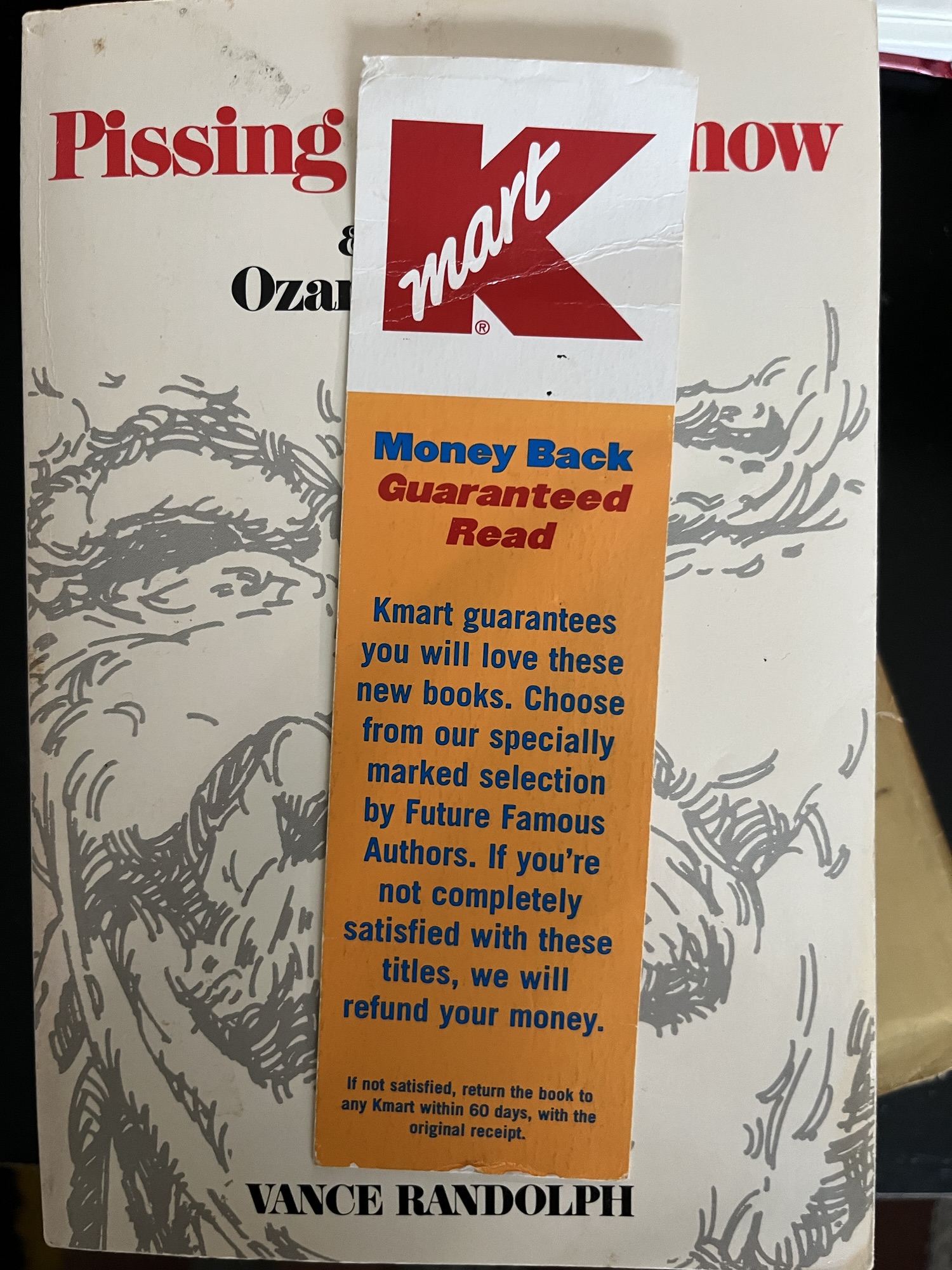

But maybe my favorite find was this Kmart bookmark:

The Kmart bookmark was tucked into a trade paperback University of Illinois Press copy of Randolph’s Pissing in the Snow. I doubt the collection of Ozark folktales was originally purchased at Kmart. But who knows.

Pissing in the Snow was one of the first books I wrote about on this blog, nearly twenty years ago. I look forward to passing it on to a student sooner or later.