I say we had best look our times and lands searchingly in the face, like a physician diagnosing some deep disease. Never was there, perhaps, more hollowness at heart than at present, and here in the United States. Genuine belief seems to have left us. The underlying principles of the States are not honestly believ’d in, (for all this hectic glow, and these melodramatic screamings,) nor is humanity itself believ’d in. What penetrating eye does not everywhere see through the mask? The spectacle is appaling. We live in an atmosphere of hypocrisy throughout. The men believe not in the women, nor the women in the men. A scornful superciliousness rules in literature. The aim of all the littérateurs is to find something to make fun of. A lot of churches, sects, &c., the most dismal phantasms I know, usurp the name of religion. Conversation is a mass of badinage. From deceit in the spirit, the mother of all false deeds, the offspring is already incalculable. An acute and candid person, in the revenue department in Washington, who is led by the course of his employment to regularly visit the cities, north, south and west, to investigate frauds, has talk’d much with me about his discoveries. The depravity of the business classes of our country is not less than has been supposed, but infinitely greater. The official services of America, national, state, and municipal, in all their branches and departments, except the judiciary, are saturated in corruption, bribery, falsehood, mal-administration; and the judiciary is tainted. The great cities reek with respectable as much as non-respectable robbery and scoundrelism. In fashionable life, flippancy, tepid amours, weak infidelism, small aims, or no aims at all, only to kill time. In business, (this all-devouring modern word, business,) the one sole object is, by any means, pecuniary gain. The magician’s serpent in the fable ate up all the other serpents; and money-making is our magician’s serpent, remaining to-day sole master of the field.

Category: Literature

“October” — Robert Frost

“Discovery” — Guy de Maupassant

The steamer was crowded with people and the crossing promised to be good. I was going from Havre to Trouville.

The ropes were thrown off, the whistle blew for the last time, the whole boat started to tremble, and the great wheels began to revolve, slowly at first, and then with ever-increasing rapidity.

We were gliding along the pier, black with people. Those on board were waving their handkerchiefs, as though they were leaving for America, and their friends on shore were answering in the same manner.

The big July sun was shining down on the red parasols, the light dresses, the joyous faces and on the ocean, barely stirred by a ripple. When we were out of the harbor, the little vessel swung round the big curve and pointed her nose toward the distant shore which was barely visible through the early morning mist. On our left was the broad estuary of the Seine, her muddy water, which never mingles with that of the ocean, making large yellow streaks clearly outlined against the immense sheet of the pure green sea.

As soon as I am on a boat I feel the need of walking to and fro, like a sailor on watch. Why? I do not know. Therefore I began to thread my way along the deck through the crowd of travellers. Suddenly I heard my name called. I turned around. I beheld one of my old friends, Henri Sidoine, whom I had not seen for ten years. Continue reading ““Discovery” — Guy de Maupassant”

“The Absence of Any Purpose Is the Starting Point for My Work” | An Interview with Roman Muradov

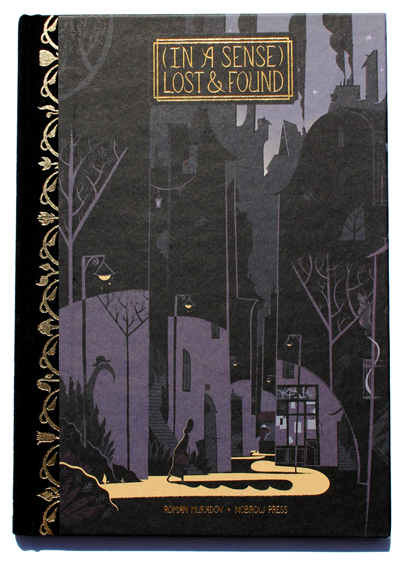

I’ve been a fan of Roman Muradov’s strange and wonderful illustrations for a while now, so I was excited late this summer to get my hands on his début graphic novella, (In a Sense) Lost and Found (Nobrow Press). In my review, I wrote: “I loved Lost and Found, finding more in its details, shadowy corners, and the spaces between the panels with each new reading.” The book is a beauty, so I was thrilled when Roman agreed to discuss it with me over a series of emails. We also discussed his influences, his audience, his ongoing Yellow Zine projects, his recent cover for Joyce’s Dubliners, and his reaction to some of the confused Goodreads reviews his novella received. Check out Roman’s work at his website. You won’t be disappointed.

Biblioklept: When did you start working on (In a Sense) Lost and Found? Did you always have the concept kicking around?

Roman Muradov: The idea came to me in 2010 in the form of the title and the image of a protracted awakening. I wrote it as a short story, which had a much more conventional development and actually had some characters and plot movements, all of them completely dropped one by one on the way to the final version apart from the basic premise. I didn’t have a clear understanding of what was to be done with that premise, but the idea kept bothering me for some time, until I rewrote it a few times into a visual novella when Nobrow asked me if I wanted to pitch them something. Since then it went through several more drafts and even after everything was drawn and colored I had to go back and edit most of the dialogues, which is a nightmarish task in comics, since it involved re-lettering everything by hand.

Biblioklept: When you say you wrote it as a short story, I’m intrigued—like, do you mean as a sketch, or a set of directions, or as a tale with imagery? Part of the style of the book (and your style in general) is a confidence in the reader and the image to work together to make the narrative happen. When you were editing the dialogues, were you cutting out exposition, cues, contours?

RM: No, I mean a traditional pictureless short story. I was struggling with forms at the time and didn’t feel confident with any of them. In a way this still persists, because my comics are often deliberately deviating from the comics form, partially in my self-published experiments. The story itself was still ambiguous, I never considered showing what she lost, or how. With time I edited down all conversation to read as one self-interrupting monologue.

Biblioklept: I want to circle back to (In a Sense) Lost and Found, but let’s explore the idea that your work intentionally departs from the conventions of cartooning. When did you start making comics? What were the early comics that you were reading, absorbing, understanding, and misunderstanding?

RM: I came to comics pretty late; I only discovered Chris Ware & co around 2009. As a child I spent one summer drawing and writing little stories, ostensibly comics, then I stopped for a couple of decades. I’m not really sure why I started or stopped. In general my youth was marked by extraordinary complacency and indifference. I followed my parents’ advice and studied petroleum engineering, then worked as a petroleum engineer of sorts for a year and a half, then quit and decided to become an artist. I still feel that none of these decisions were made by me. Occasionally certain parts of my work seem to write themselves and I grow to understand them much later, which is weird.

Biblioklept: Was Ware a signal figure for you? What other comic artists did you find around that time?

Ware, Clowes & Jason were the first independent cartoonist I discovered and I ended up ripping them off quite blatantly for a year or so. Seth was also a big influence, particularly his minute attention to detail and his treatment of time, the way he stretches certain sequences into pages and pages, then skips entire plot movements altogether. Reading Tim Hensley’s Wally Gropius was a huge revelation, it felt like I was given permission to deviate from the form. Similarly, I remember reading Queneau’s “Last Days” in Barbara Wright’s translation, and there was the phrase “the car ran ovaries body” or something like that, and I thought “oh, I didn’t know this was allowed.”

Biblioklept: Your work strikes me as having more in common with a certain streak of modernist and postmodernist prose literature than it does with alt comix. Were you always reading literature in your petroleum engineer days?

RM: That’s certainly true, nowadays I’m almost never influenced by other cartoonists. I wasn’t a good reader until my mid-twenties, certainly not back in Russia. I stumbled upon Alfred Jarry (not in person) while killing time in the library, and then it was a chain reaction to Quenau, Perec and Roussel, then all the modernists and postmodernists, particularly Kafka, Joyce, Nabokov and Proust.

Biblioklept: How do you think those writers—the last four you mention in particular—influence your approach to framing your stories?

RM: From Nabokov I stole his love for puzzles and subtle connections, a slightly hysterical tone, his shameless use of puns and alliteration, from Kafka–economy of language and a certain mistrust of metaphors–it always seems to me that his images and symbols stretch into an infinite loop defying straightforward interpretation by default, from Joyce and Proust the mix of exactitude and vagueness, and the prevalence of style over story, the choreography of space and time. I should’ve say “I’m in the process of stealing,” I realize that all of these things are far too complex, and I doubt that I’ll ever feel truly competent with any of these authors as a reader, let alone as a follower.

Biblioklept:(In a Sense) Lost and Found begins with a reference to Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and then plunges into a Kafkaesque—to use your phrasing—“infinite loop defying straightforward interpretation.” How consciously were you following Kafka’s strange, skewed lead?

RM: I wanted the reference to be as obvious as possible, almost a direct copy, as if it’s placed there as an act of surrender–I’m not going to come up with a story, here’s one of most famous opening lines that you already know. Usually I know the beginning and the ending and I often downplay their importance, so that the work becomes focused mostly on the process and so that readers don’t expect any kind of resolution or satisfactory narrative development. In the password scene the phrases are copied directly from Eliot’s Wasteland, which itself refers to Paradise Lost in these passages. It’s a bit like a broken radio, shamelessly borrowing from the narrator’s visual and literary vocabulary, the way it happens in a dream.

“The Chemist’s Wife” — Anton Chekhov

“The Chemist’s Wife”

by

Anton Chekhov

The little town of B——, consisting of two or three crooked streets, was sound asleep. There was a complete stillness in the motionless air. Nothing could be heard but far away, outside the town no doubt, the barking of a dog in a thin, hoarse tenor. It was close upon daybreak.

Everything had long been asleep. The only person not asleep was the young wife of Tchernomordik, a qualified dispenser who kept a chemist’s shop at B——. She had gone to bed and got up again three times, but could not sleep, she did not know why. She sat at the open window in her nightdress and looked into the street. She felt bored, depressed, vexed . . . so vexed that she felt quite inclined to cry—again she did not know why. There seemed to be a lump in her chest that kept rising into her throat. . . . A few paces behind her Tchernomordik lay curled up close to the wall, snoring sweetly. A greedy flea was stabbing the bridge of his nose, but he did not feel it, and was positively smiling, for he was dreaming that every one in the town had a cough, and was buying from him the King of Denmark’s cough-drops. He could not have been wakened now by pinpricks or by cannon or by caresses.

The chemist’s shop was almost at the extreme end of the town, so that the chemist’s wife could see far into the fields. She could see the eastern horizon growing pale by degrees, then turning crimson as though from a great fire. A big broad-faced moon peeped out unexpectedly from behind bushes in the distance. It was red (as a rule when the moon emerges from behind bushes it appears to be blushing).

Suddenly in the stillness of the night there came the sounds of footsteps and a jingle of spurs. She could hear voices. Continue reading ““The Chemist’s Wife” — Anton Chekhov”

Harold Bloom on Wallace Stevens

The dark patches fall (Walt Whitman)

They will not do us any good—the good books (William H. Gass)

They will not do us any good—the good books—no—if by good we mean good looks, good times, good shoes; yet they still offer us salvation, for salvation does not wait for the next life, which is anyhow a vain and incautious delusion, but is to be had, if at all, only here—in this one. It is we who must do them honor by searching for our truth there, by taking their heart as our heart, by refusing to let our mind flag so that we close their covers forever, and spend our future forgetting them, denying the mind’s best moments. They extend the hand; we must grip it. Spinach never made Popeye strong sitting in the can. And the finest cookbook ever compiled put not one pot upon the stove or dish upon the table. Here, in the library that has rendered you suspect, you have made their acquaintance—some of the good books. So now that you’ve been nabbed for it, you must become their lover, their friend, their loyal ally. But that is what the rest of your life is for. Go now, break jail, and get about it.

From William H. Gass’s essay “To a Young Friend Charged with Possession of the Classics.” Collected in A Temple of Texts.

“On Being in the Blues” — Jerome K. Jerome

“On Being in the Blues”

by

Jerome K. Jerome

I can enjoy feeling melancholy, and there is a good deal of satisfaction about being thoroughly miserable; but nobody likes a fit of the blues. Nevertheless, everybody has them; notwithstanding which, nobody can tell why. There is no accounting for them. You are just as likely to have one on the day after you have come into a large fortune as on the day after you have left your new silk umbrella in the train. Its effect upon you is somewhat similar to what would probably be produced by a combined attack of toothache, indigestion, and cold in the head. You become stupid, restless, and irritable; rude to strangers and dangerous toward your friends; clumsy, maudlin, and quarrelsome; a nuisance to yourself and everybody about you.

While it is on you can do nothing and think of nothing, though feeling at the time bound to do something. You can’t sit still so put on your hat and go for a walk; but before you get to the corner of the street you wish you hadn’t come out and you turn back. You open a book and try to read, but you find Shakespeare trite and commonplace, Dickens is dull and prosy, Thackeray a bore, and Carlyle too sentimental. You throw the book aside and call the author names. Then you “shoo” the cat out of the room and kick the door to after her. You think you will write your letters, but after sticking at “Dearest Auntie: I find I have five minutes to spare, and so hasten to write to you,” for a quarter of an hour, without being able to think of another sentence, you tumble the paper into the desk, fling the wet pen down upon the table-cloth, and start up with the resolution of going to see the Thompsons. While pulling on your gloves, however, it occurs to you that the Thompsons are idiots; that they never have supper; and that you will be expected to jump the baby. You curse the Thompsons and decide not to go. Continue reading ““On Being in the Blues” — Jerome K. Jerome”

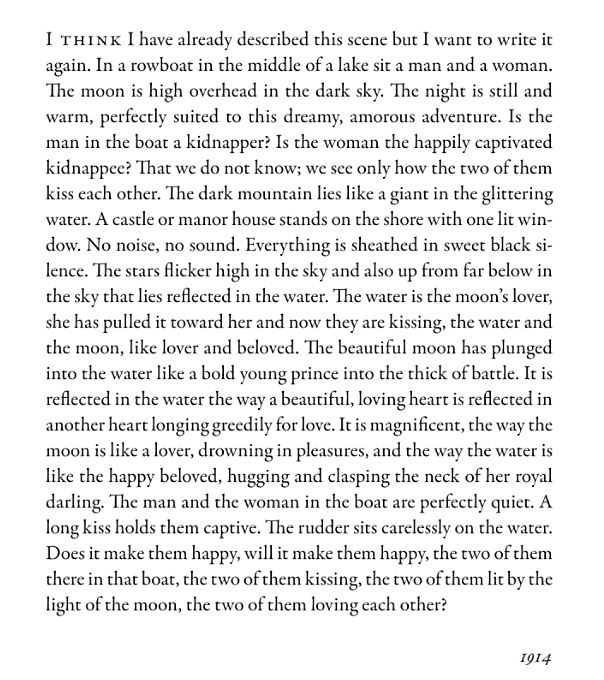

“The Rowboat” — Robert Walser

“Secret Breathing Techniques” — Ben Marcus

I HAD APPARENTLY BEEN living in one of the towns that was now gone. According to reports, I held my own against one of the younger organizations. I fought well and long. The ending of the report is muddy, with many foreign words and phrases, and an indecipherable series of pictures. There is no clear sense that I survived.

Photographs of my body had circulated, flags had been stitched with secret instructions.

There were instances of my name in the registry—the spelling varied, and my date of birth was frequently listed as unknown. A scroll of hair, probably my own, was taped to the paper. Mention was made of what must have been my house, a vehicle I summoned to cross the water (skirmishes, courtship, evasions—the report is unclear), and the amount of sacking I had contributed to the yearly mountain effort. I ranked slightly above average.

People wrote of seeing me in the morning by the water; several photographs featured me wearing a beard, concealing something in my coat. A Nacht diagram rated me favorably, prior to the revision. The Wixx index claimed I might have perished. I read accounts of myself ostensibly accompanying a family to the market on Saturdays. I may have been their assistant; I may have been their captor. The wording is vague. Some sentences depicted me handling the bread in an aggressive manner, as if searching for something inside it.

It is possible I was collecting samples. I would not rule it out. It would explain the long clear jars I found stored in my clothing that day when I woke. But it would not explain why those jars were empty.

Read the rest of “Secret Breathing Techniques” by Ben Marcus in Conjunctions.

“The Motive for Metaphor” — Wallace Stevens

“The Motive for Metaphor”

by

Wallace Stevens

You like it under the trees in autumn,

Because everything is half dead.

The wind moves like a cripple among the leaves

And repeats words without meaning.

In the same way, you were happy in spring,

With the half colors of quarter-things,

The slightly brighter sky, the melting clouds,

The single bird, the obscure moon–

The obscure moon lighting an obscure world

Of things that would never be quite expressed,

Where you yourself were not quite yourself,

And did not want nor have to be,

Desiring the exhilarations of changes:

The motive for metaphor, shrinking from

The weight of primary noon,

The A B C of being,

The ruddy temper, the hammer

Of red and blue, the hard sound–

Steel against intimation–the sharp flash,

The vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X.

September 23, 1843 — From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Journal

September 23d.–I have gathered the two last of our summer-squashes to-day. They have lasted ever since the 18th of July, and have numbered fifty-eight edible ones, of excellent quality. Last Wednesday, I think, I harvested our winter-squashes, sixty-three in number, and mostly of fine size. Our last series of green corn, planted about the 1st of July, was good for eating two or three days ago. We still have beans; and our tomatoes, though backward, supply us with a dish every day or two. My potato-crop promises well; and, on the whole, my first independent experiment of agriculture is quite a successful one.

This is a glorious day,–bright, very warm, yet with an unspeakable gentleness both in its warmth and brightness. On such days it is impossible not to love Nature, for she evidently loves us. At other seasons she does not give me this impression, or only at very rare intervals; but in these happy, autumnal days, when she has perfected the harvests, and accomplished every necessary thing that she had to do, she overflows with a blessed superfluity of love. It is good to be alive now. Thank God for breath,–yes, for mere breath! when it is made up of such a heavenly breeze as this. It comes to the cheek with a real kiss; it would linger fondly around us, if it might; but, since it must be gone, it caresses us with its whole kindly heart, and passes onward, to caress likewise the next thing that it meets. There is a pervading blessing diffused over all the world. I look out of the window and think, “O perfect day! O beautiful world! O good God!” And such a day is the promise of a blissful eternity. Our Creator would never have made such weather, and given us the deep heart to enjoy it, above and beyond all thought, if he had not meant us to be immortal. It opens the gates of heaven and gives us glimpses far inward.

Bless me! this flight has carried me a great way; so now let me come back to our old abbey. Our orchard is fast ripening; and the apples and great thumping pears strew the grass in such abundance that it becomes almost a trouble–though a pleasant one–to gather them. This happy breeze, too, shakes them down, as if it flung fruit to us out of the sky; and often, when the air is perfectly still, I hear the quiet fall of a great apple. Well, we are rich in blessings, though poor in money. . . .

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

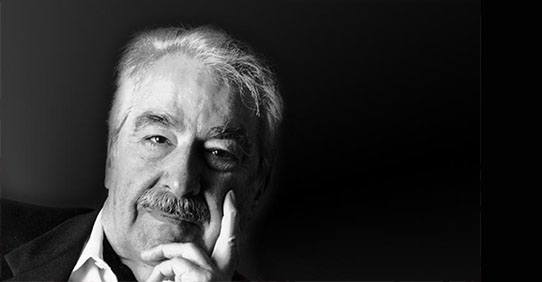

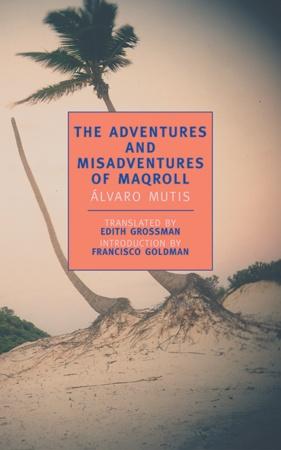

Reviving Álvaro Mutis, Who Died One Year Ago Today

The Colombian writer Álvaro Mutis died one year ago today.

Mutis wasn’t on my radar until a few years ago, when a friend of mine, Dave Cianci, urged me to read the author’s opus, The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll, a collection of seven novellas that speak to each other in a loose, rich, intertextual poetics of adventure, romance, and loss. My friend Cianci was so enthusiastic about the book that he reviewed it for this blog (the review convinced me to read it). I’ll crib from that review:

The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll is difficult to categorize. It’s an outlaw adventure story populated by men and women who live where and how they must; these are the people who work near shipyards and the banks of unexplored river tributaries, people who value candor and honesty but for whom strict adherence to the law is often inconvenient. The book is a philosophical rumination on friendship and creation, romance and deception, obstinance and poverty.

Later in his review, Cianci characterizes the titular Maqroll—the Gaviero, the “lookout” —as “who we all dream of being when we contemplate throwing everything away.” In one of my own pieces on Maqroll, I described the world that Mutis offers, part fantasy, part nightmare, as

a life of picaresque adventures (and titular misadventures), of loss and gain, of love and despair, drinking, sailing, scheming and plotting—a life full of allusions and hints and digressions. Mutis’s technique is marvelous (literally; he made this reader marvel): he gives us an aging (anti-)hero, a hero whose life is overstuffed with stories and mishaps and feats and enterprises and hazards; he gives us one strand of that life at a time in each novella—but then he points to the other adventures, the other serials of Maqroll that we would love to tune into if only we could.

John Updike explained the attraction to Mutis and Maqroll in his 2003 New Yorker review of NYRB’s Maqroll collection:

The problem of energy, in this enervated postmodern era, keeps arising in Mutis’s pursuit of a footloose, offhandedly erudite, inexplicably attractive shady character. A lowly seaman with some high-flying acquaintances on land, Maqroll is a drifter who tends to lose interest in his adventures before the dénouement is reached. Readers even slightly acquainted with Latin-American modernism will hear echoes of Borges’s cosmic portentousness, of Julio Cortázar’s fragmenting ingenuities, of Machado De Assis’s crisp pessimism, and of the something perversely hearty in Mutis’s fellow-Colombian and good friend Gabriel García Márquez—a sense of genial amplitude, as when a ceremonious host sits us down to a lunch provisioned to stretch into evening. Descriptions of food consumed and of drinks drunk, amid flourishes of cosmopolitan connoisseurship, are frequent in Mutis, even as the ascetic Maqroll goes hungry. North Americans may be reminded of Melville—more a matter, perhaps, of affinity than of influence.

Updike’s review is one of the only prominent and long English-language pieces about Álvaro Mutis that I’ve come across. There’s a good 2001 interview with Mutis in Bomb by Francisco Goldman (who wrote the NYRB edition’s introduction), and a few translated poems of Mutis’s can be found online, but on the whole, despite accolades throughout the Spanish-reading world, his reputation among English-readers seems relegated to “friend of Gabriel Garcia Marquez” (who called Mutis “one of the greatest writers of our time”).

Álvaro Mutis deserves a bigger English-reading audience. NYRB’s collection of his novellas in Edith Grossman’s translation bristles with energy. At once accessible and confounding, these tales that ask us to read them again, like Borges’s puzzles Bolaño’s labyrinths.

Is it tactless to name Bolaño here? Maybe—he’s perhaps too-easy an example: A Spanish-language author whose readership radically expanded after his death. Anyone who follows literary trends (ach!) will see how quickly a writer’s currency elevates after his or her death. (Ach! again). But I think that Mutis should attract fans of Bolaño, whose currency still spends (and will spend in the future, I think). Another comparison I would like to be able to make though would be John Williams’s sad novel Stoner, which, as any one who follows literary trends (ach!) could tell you became an unexpected best seller last year. Stoner—also published by the good people at NYRB—had to wait half a century to get its due. I don’t see why the English-reading world should wait that long to embrace Mutis.

“The Man of the Crowd” — Edgar Allan Poe

Harry Clarke’s illustration for “The Man of the Crowd,” 1923

“The Man of the Crowd”

by

Edgar Allan Poe

Ce grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul.

La Bruyère.

IT was well said of a certain German book that “er lasst sich nicht lesen“—it does not permit itself to be read. There are some secrets which do not permit themselves to be told. Men die nightly in their beds, wringing the hands of ghostly confessors and looking them piteously in the eyes—die with despair of heart and convulsion of throat, on account of the hideousness of mysteries which will not suffer themselves to be revealed. Now and then, alas, the conscience of man takes up a burthen so heavy in horror that it can be thrown down only into the grave. And thus the essence of all crime is undivulged.

Not long ago, about the closing in of an evening in autumn, I sat at the large bow window of the D——- Coffee-House in London. For some months I had been ill in health, but was now convalescent, and, with returning strength, found myself in one of those happy moods which are so precisely the converse of ennui—moods of the keenest appetency, when the film from the mental vision departs—the [Greek phrase]—and the intellect, electrified, surpasses as greatly its every-day condition, as does the vivid yet candid reason of Leibnitz, the mad and flimsy rhetoric of Gorgias. Merely to breathe was enjoyment; and I derived positive pleasure even from many of the legitimate sources of pain. I felt a calm but inquisitive interest in every thing. With a cigar in my mouth and a newspaper in my lap, I had been amusing myself for the greater part of the afternoon, now in poring over advertisements, now in observing the promiscuous company in the room, and now in peering through the smoky panes into the street.

This latter is one of the principal thoroughfares of the city, and had been very much crowded during the whole day. But, as the darkness came on, the throng momently increased; and, by the time the lamps were well lighted, two dense and continuous tides of population were rushing past the door. At this particular period of the evening I had never before been in a similar situation, and the tumultuous sea of human heads filled me, therefore, with a delicious novelty of emotion. I gave up, at length, all care of things within the hotel, and became absorbed in contemplation of the scene without. Continue reading ““The Man of the Crowd” — Edgar Allan Poe”

A Conversation about Ben Lerner’s Novel 10:04 (Part 2)

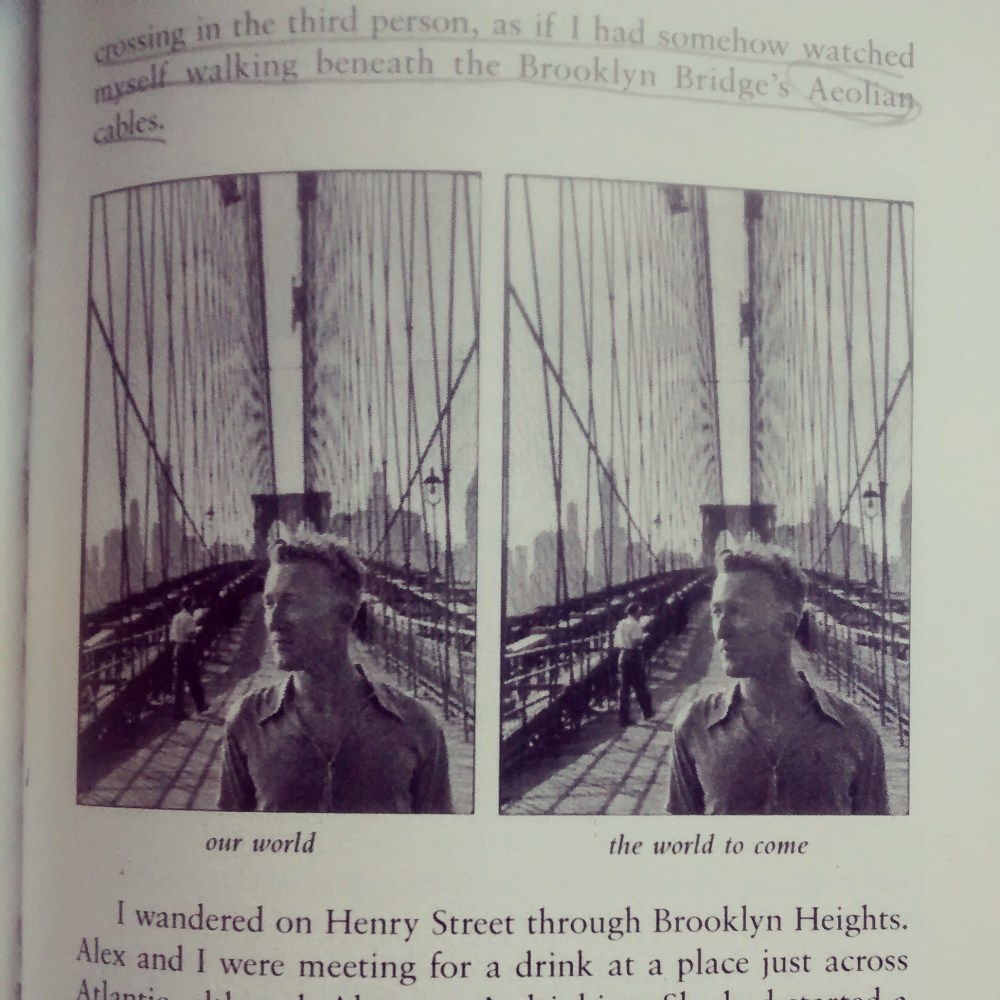

Does [the novel’s] ironic tone (which often feels like a reflex, a tic) preclude sincerity? Is all this talk of community no more than an artful confection, the purest kind of cynicism? The question is impossible to resolve, so each of these episodes — and indeed the book as a whole — takes on a sort of hermetic undecidability.

Ryan Chang: Hey man, I just skimmed the NYT review—per the excerpt you provided—because I don’t want Kunzru clouding any of my response. It’s certainly a question I too grapple with, and I think Kunzru is right insofar that the question is “undecidable” but not for the reason(s) he suggests. I agree with you that he dodges the question, whether or not from editorial pressure or a reticence to actually address “hermetic undecidability.”

For one, I’m not sure myself if The Author ever arrives at the Whitmanic model of democracy he posits. I’m also not sure if he is supposed to “arrive” in the sense that a finality is set. I guess I also want to riff a bit on how finality might be described. Is finality then something static; as in, somehow 10:04 transmits–electrocutes, reverberates–through its readership, now coeval (the when negligent, the position of the reader enmeshed in the text is the same at 10 PM here as it is at 5 AM there), the novel’s theses and everything is suddenly Whitmanic? Community successfully reimagined and cemented? That sounds too easy, too convenient, too short-sighted. Or is it a kind of arrival into an embodiment of time that exists outside of conventional literary clocks, which is also a Market-based clock — it’s my sense that the kind of democracy Whitman envisions in his work is one constantly in flux, a “reality in process” and thus in opposition to the capitalist clock? That is, we know we are supposed to “stop” working at 5, the embodiment of the currency-based clock disappears after 5, but it’s a contrasting relationship. Our time outside of the currency then absorbs a negative value (I think The Author only mentions once or twice how we are all connected by our debt, a negativity projected into the future), though the illusion of the clock is that we are “free” in our time. OK: in a literary sense, wouldn’t this be a sense of a text’s world stopping, a suspension that retroactively pauses the whole book? That 10:04 ends not only with a dissolution of prose into poetry, but also The Author into Whitman and thus recasting the first-/third-person narrator into a lyric-poet mode suggests the book’s integration into our, the reader’s, time (and also, retroactively, the entirety of the text). In that sense, for me, the issue whether or not The Author of 10:04 integrates the book fully into a Whitmanic model is not necessarily the point — it is that he, and also we hopefully through him — actively participate in remaking a “bad form of collectivity” less so. Continue reading “A Conversation about Ben Lerner’s Novel 10:04 (Part 2)”

“Clay” — James Joyce

“Clay”

by

James Joyce

The matron had given her leave to go out as soon as the women’s tea was over and Maria looked forward to her evening out. The kitchen was spick and span: the cook said you could see yourself in the big copper boilers. The fire was nice and bright and on one of the side-tables were four very big barmbracks. These barmbracks seemed uncut; but if you went closer you would see that they had been cut into long thick even slices and were ready to be handed round at tea. Maria had cut them herself.

Maria was a very, very small person indeed but she had a very long nose and a very long chin. She talked a little through her nose, always soothingly: “Yes, my dear,” and “No, my dear.” She was always sent for when the women quarrelled over their tubs and always succeeded in making peace. One day the matron had said to her:

“Maria, you are a veritable peace-maker!”

And the sub-matron and two of the Board ladies had heard the compliment. And Ginger Mooney was always saying what she wouldn’t do to the dummy who had charge of the irons if it wasn’t for Maria. Everyone was so fond of Maria.

The women would have their tea at six o’clock and she would be able to get away before seven. From Ballsbridge to the Pillar, twenty minutes; from the Pillar to Drumcondra, twenty minutes; and twenty minutes to buy the things. She would be there before eight. She took out her purse with the silver clasps and read again the words A Present from Belfast. She was very fond of that purse because Joe had brought it to her five years before when he and Alphy had gone to Belfast on a Whit-Monday trip. In the purse were two half-crowns and some coppers. She would have five shillings clear after paying tram fare. What a nice evening they would have, all the children singing! Only she hoped that Joe wouldn’t come in drunk. He was so different when he took any drink. Continue reading ““Clay” — James Joyce”