* * * * *

The hen sparrow believes that her cock sparrow is not chirping but singing beautifully.

* * * * *

When one is peacefully at home, life seems ordinary, but as soon as one walks into the street and begins to observe, to question women, for instance, then life becomes terrible. The neighborhood of Patriarshi Prudy (a park and street in Moscow) looks quiet and peaceful, but in reality life there is hell.

* * * * *

These red-faced young and old women are so healthy that steam seems to exhale from them.

* * * * *

The estate will soon be brought under the hammer; there is poverty all round; and the footmen are still dressed like jesters.

* * * * *

There has been an increase not in the number of nervous diseases and nervous patients, but in the number of doctors able to study those diseases.

* * * * *

The more refined the more unhappy.

* * * * *

Life does not agree with philosophy: there is no happiness which is not idleness and only the useless is pleasurable.

* * * * *

The grandfather is given fish to eat, and if it does not poison him and he remains alive, then all the family eat it.

* * * * *

A correspondence. A young man dreams of devoting himself to literature and constantly writes to his father about it; at last he gives up the civil service, goes to Petersburg, and devotes himself to literature—he becomes a censor.

* * * * *

Category: Literature

“Physiognomy of a Dog” — Ryan Chang

Frequent Biblioklept contributor Ryan Chang’s new short story, “Physiognomy of a Dog” (about shame and feces and etc.) is up now at Hypothetical. Here’s a taster:

It’s come to my attention that a rumor, of which I am the sole authority to its verity, has been pinging through the halls of our fine institution. He, the normal student, M—, enrolled in a program that would take at least one hundred years to complete—this being the exception, established by the Exceptional Student—supposedly reported to me that were it not for the existence of such an exception his “anxieties and pains” may have been relieved; the dream of graduation in just 99 years would not have evaporated. Red-rashed, he’d said, according to the halls, the normal student rushed a letter to the Advisory, only to be told to consult the framed statement on the wall that details the circumstances of this particular exception; he’d see it on his way to the Advisory, near the door to the infirmary, which often doubles as our morgue.—Before I continue, the Advisory, the governing body pro-tem, now entering its seventh century, having caught wind of this normal student’s experience, would have me preface this with the acknowledgment of said student’s discomforts, and their, let’s say, profound effects.

Read the rest of “Physiognomy of a Dog.”

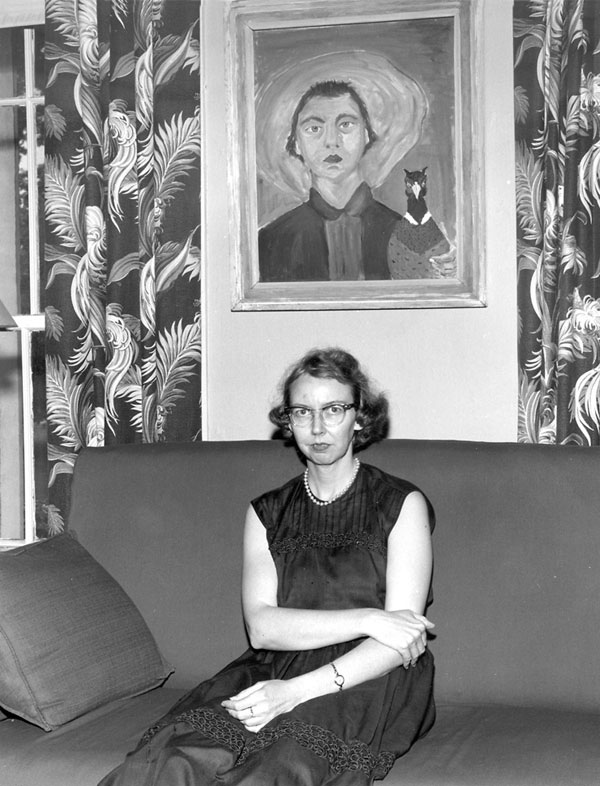

Flannery O’Connor Sitting Under Her Self-Portrait

“On Angels” — Donald Barthelme

“On Angels”

by Donald Barthelme

The death of God left the angels in a strange position. They were overtaken suddenly by a fundamental question. One can attempt to imagine the moment. How did they look at the instant the question invaded them, flooding the angelic consciousness, taking hold with terrifying force? The question was,”What are angels?”

New to questioning, unaccustomed to terror, unskilled in aloneness, the angels (we assume) fell into despair.

The question of what angels “are” has a considerable history. Swedenborg, for example, talked to a great many angels and faithfully recorded what they told him. Angels look like human beings, Swedenborg says. “That angels are human forms, or men, has been seen by me a thousand times.” And again:”From all my experience, which is now of many years, I am able to state that angels are wholly men in form, having faces, eyes, ears, bodies, arms, hands, and feet…” But a man cannot see angels with his bodily eyes, only with the eyes of the spirit.

Swedenborg has a great deal more to say about angels, all of the highest interest: that no angel is ever permitted to stand behind another and look at the back of his head, for this would disturb the influx of good and truth from the Lord; that angels have the east, where the Lord is seen as a sun, always before their eyes; and that angels are clothed according to their intelligence. “Some of the most intelligent have garments that blaze as if with flame, others have garments that glisten as if with light; the less intelligent have garments that are glistening white or white without the effulgence; and the still less intelligent have garments of various colors. But the angels of the inmost heaven are not clothed.”

All of this (presumably) no longer obtains.

Gustav Davidson, in his useful Dictionary of Angels, has brought together much of what is known about them. Their names are called: the angel Elubatel, the angel Friagne, the angel Gaap, the angel Hatiphas (genius of finery), the angel Murmur (a fallen angel), the angel Mqttro, the angel Or, the angel Rash, the angel Sandalphon (taller than a five hundred years’ jouney on foot), the angel Smat. Davidson distinguishes categories: Angels of Quaking, who surround the heavenly throune, Masters of Howling and Lords of Shouting, whose work is praise; messengers, mediators, watchers, warners. Davidson’s Dictionary is a very large book; his bibliography lists more than eleven hundred items.

The former angelic consciousness has been most beautifully described by Joseph Lyons (in a paper titles The Psychology of Angels published in 1957). Each angel, Lyons says, knows all that there is to know about himself and every ohter angel. “No angel could ever ask a question, because questioning proceeds out of situation of not knowing, and of being in some way aware of not knowing. An angel cannot be curious; he has nothing to be curious about. He cannot wonder. Knowing all that there is to know, the world of possible knowledge must appear to him as as ordered set of facts which is completely behind him, completely fixed and certain and within his grasp…”

But this, too, no longer obtains.

It is a curiosity of writing about angels that, very often, one turns outto be writing about men. The themes are twinned. Thus one finally learns that Lyons, for example, is really writing not about angels but about schizophrenics–thinking about men by invoking angels. And this holds true of much other writing on the subject– a point, we may assume, that was not lost on the angels when they began considering their new relation to the cosmos, when the analogues (is an angel more like a quetzal or more like a man? or more like music?) were being handed about.

We may frther assume that some attempt was made at self-definition by function. An angel is what he does. Thus it was necessary to investigate possible new roles (you are reminded that this is impure speculation). After the lamentation had gone on for hundreds and hundreds of whatever the angels use for time, an angel proposed that lamentation be the function of angels eternally, as adoration was formerly. The mode of lamentation would be silence, in contrast to the unceasing chanting of Glorias that had been their former employment. But it is not in the nature of angels to be silent.

A counterproposal was that the angels affirm chaos. There were to be five great proofs of the existence of chaos, of which the first was the abscence of God. The other four could surely be located. The work of definition and explication could, if done nicely enough, occupy the angels forever, as the contrary work has occupied human theologians. But there is not much enthusiasm for chaos among the angels.

The most serious because most radical proposal considered by the angels was refusal –that they would remove themselves from being, not be. The tremendous dignity that would accrue to the angels by this act was felt to be a manifestation of spiritual pride. Refusal was refused.

There were other suggestions, more subptle and complicated, less so, none overwhelmingly attractive.

I saw a famous angel on television; his garments glistened as if with light. He talked about the situation of angels now. Angels, he said are like men in some ways. The problem of adoration is felt to be central. He said that for a time the angels had tried adoring each other, as we do, but had found it, finally, “not enough.” He said they are continuing to search for a new principle.

I did some digital coloring pages of famous writers

“Caterpillar” — Christina Rossetti

Ravens and bats swarm as Don Quixote hacks a passage into the cave of Montesinos (Gustave Dore)

“The world was at war, sillies” (William H. Gass)

The world was at war, sillies. Everywhere. It was a very large war, deserving the name of “World.” It contained countless smaller ones, and the smaller ones were made of campaigns and battles, deadly encounters and single shootings, calamities on all fronts. But history can hold up for our inspection many different sorts of wars, and World War Two was made of nearly all of them: trade wars—tribal wars—civil wars—wars by peaceful means—wars of ideas—wars over oil—over opium—over living space—over access to the sea—whoopee, the war in the air—among feudal houses—raw raw siss-boom-bah—so many to choose from—holy wars—battles on ice floes between opposing ski patrols—by convoys under sub pack attacks—in the desert there might be a dry granular war fought between contesting tents, dump trucks, and tanks—or—one can always count on the perpetual war between social classes—such as—whom do you suppose? the Rich, the Well Off, the Sort Of, the So-So, and the Starving—or—the Smart, the Ordinary, and the Industriously Ignorant—or—the Reactionary and the Radical—not just the warmongers for war but those conflicts by pacifists who use war to reach peace—the many sorts of wars that old folks arrange, the middle-aged manage, and the young fight—oh, all of these, and sometimes simultaneously—not to neglect the wars of pigmentation: color against color, skin against skin, slant versus straight, the indigenous against immigrants, city slickers set at odds with village bumpkins, or in another formulation: factory workers taught to shake their fists at field hands (that’s hammer at sickle)—ah, yes—the relevant formula, familiar to you, I’m sure, is that scissors cut paper, sprawl eats space—Raum!—then in simpler eras, wars of succession—that is, wars to restore some king to his john or kill some kid in his cradle—wars between tribes kept going out of habit—wars to keep captured countries and people you have previously caged, caged—wars in search of the right death, often requiring suicide corps and much costly practice—wars, it seems, just for the fun of it, wars about symbols, wars of words—uns so weiter—wars to sustain the manufacture of munitions—bombs, ships, planes, rifles, cannons, pistols, gases, rockets, mines—wars against scapegoats to disguise the inadequacies of some ruling party—a few more wars—always a few more, wars fought to shorten the suffering, unfairness, and boredom of life.

From William H. Gass’s novel Middle C.

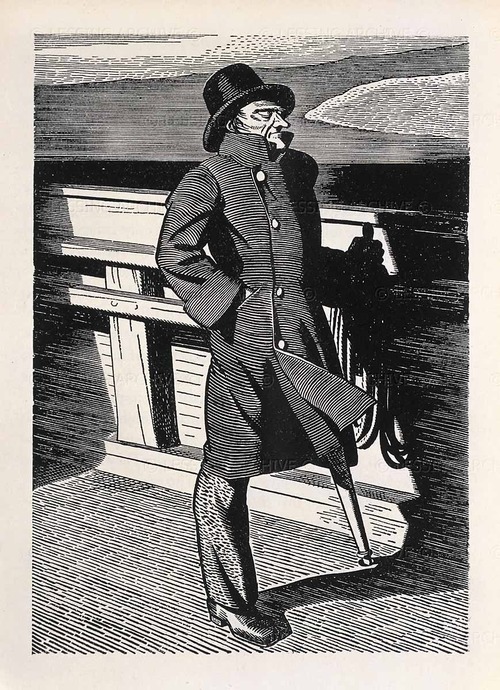

Ahab — Rockwell Kent

“The Bohemian Dinner” — Charles Green Shaw

Scenes from the Inhumanity Museum (William H. Gass)

416 b.c. Athens besieges the island colony of Melos, an ally of Sparta, during the Peloponnesian War. Melos is chosen for its particular weakness and to prove to others the power of Athens. The Melians refuse to surrender because it would look bad on their résumé (they were a shame society) and result in slavery for their citizens. The Athenians decimate the population by killing the men and boys, taking the women into service, and later repopulate the place with their own kind.

149–146 b.c. Weakened by its victory at Cannae during the Second Punic War, the Romans, who simply outlasted their foe, burned Carthaginian ships, the pride of the sea, in their own harbor, then murdered the men, raped the women, and rampaged each street. Fifty thousand were sold into slavery, although, with such a plentiful harvest, prices could not have been advantageous. Emptied of all contents, the city was razed and left in shards and shatters, but scholars (the pen exceeding the sword once again) waited until the nineteenth century to salt the very earth the city once stood on. It made for a better story. I can only agree.

339. Because, among the Jews and the Magi, the number of Assyrians was, in clear evidence, multiplying, a firman was issued (possibly called a fatwa now) that doubled their taxes. Mar Shimun, head of the Assyrian cities of Seleusa and Ctesiphon, refused to enforce this levy, so it was carried out by collectors of particular violence and brutality in the hope that the Christians would abjure their religion in order to escape taxation and mistreatment. Just in case they did not, on the morning of Good Friday, 339, he had Shimun arrested for treason, all Assyrian vessels seized by the government, priests and ministers put to the sword, and churches torn from their moorings in the earth.

1200 et passim. Genghis Khan carried out mass murders in many of the cities he conquered, Baghdad, Samarkand, Urgench, Vladimir, and Kiev among them. Afterward, he appeared in several inferior films I have been forced by my mother to see.

1850–1890. Having infected the natives of America with smallpox, pushed them from their hunting grounds, thrashed them thoroughly in small engagements over many years, broken numerous treaties and agreements, the colonists resorted to death marches and emaciating dislocations over a period of nearly fifty years (the Trail of Tears that followed the Indian Removal Act in 1830 rid us of four thousand). Feeling a bit ashamed about collecting more scalps than the barbaric tribesmen, the white man made amends with bad booze, attic rugs, and baby rattles. The final indignity, in our present age, is permission we have given to the tribes to oversee and profit from tawdry gambling casinos erected on their reservations. Liquor and various drugs are available at cut rates, especially near borders. Speaking of borders, Dominican dictator Trujillo ordered all cattle-rustling Haitians, living close to the republic’s legal edges, be eliminated. Twenty to thirty thousand were—more than the number of cattle. Haitians speak a sort of French, Dominicans a pretty good Spanish, but the nationalities may otherwise be indistinguishable. The test chosen by their murderers was to require their suspect to identify a sprig of parsley: what is this? Instead of our present choice of curly or flat, Haitians would either say persil or pèsi instead of the Dominican perejil. Nazis were no doubt similarly inspired to inspect their prey for circumcisions. Australians treated their indigenous populations rather as Americans did. They began with measles and smallpox, concluded with sabering, burning, and shooting. Tasmanian aborigines were nearly exterminated, but, like the buffalo, have since made a comeback, so all is well. Some claim our pacification program in the Philippines (1902–13), using cholera to do most of the damage, killed more than a million Filipinos, some of whom were actually dissidents. Nazis were no doubt similarly inspired by these advances in germ warfare to encourage families of malarial mosquitoes to set up shop in the Pontine Marshes where they produced ninety-eight thousand cases in only two years. Nazis were no doubt similarly inspired by their own example in German South-West Africa. They gave to history its first case, it is claimed, of state-organized genocide, led by a man perfectly named for it—General Lothar von Trotha. Two ethnic groups made up the colony’s population. The general removed 80 percent of one but scarcely 50 percent of the other. [Required two cards]

1639–1651. Cromwell’s army invaded Ireland to deny Royalists their farms and to put many of these properties in Protestant hands, at the same time preventing them from serving as a base for the return of the Crown to England. Colonization was indeed a British habit. When the French explored the New World they built outposts to facilitate trade; when the Spanish did so, after the initial slaughter, they settled in among the natives, often marrying them; but when the British arrived they drove the Indians away and built houses for themselves and handsome sideboards for their manners. This was not a new strategy but a successful one, except in Ireland’s case. Nazis were no doubt similarly inspired to repopulate Poland, as the Israelis to enlarge Zion. The Irish were encouraged to remain bitter by British behavior during the potato famine of 1845–49. The Brits outpaid the Irish for their own crop, vesseled the potatoes away, and left the people to starve. Stupid, stubborn, slippery: the British do not own these qualities, but in England’s case, they built an empire with them. The Irish moved to big-city America where they became cops. In their spare time, some rioted with German immigrants over saloon hours.

1793–1796. A part of France called Vendée was a persistent arena of religious conflict. It is difficult to separate the killing and maiming that takes place during a war with the sort that qualifies for the Inhumanity Museum. They didn’t want to pay taxes. (I’ve heard that before.) This time the tax was to be paid by their church. Economics and religion will always set a place blazing. At first, supporters of the church and Crown prevailed, the insurgency seemed on the point of success; but the new bloodthirsty Republican state sent a huge army to “pacify” the region by killing most of the people in it. Until these ruffians arrived, there was not enough “inhumanity” to qualify it for membership. Women and children, houses and municipal buildings, flags and symbols, were all equally eradicated. Beliefs had sharp queries run through them, but beliefs, however stupid or foolish or bizarre, have no more material a body than God himself. They cannot be so easily destroyed, and always outlive their believers, if only in quaint volumes and old tomes. There they lie until some half-wit gives them animation.

From William H. Gass’s novel Middle C.

Teju Cole’s Every Day Is for the Thief (Book Acquired, 3.17.2014)

Teju Cole’s Open City is one of my favorite novels of recent years, so I was psyched when Every Day Is for the Thief (which is kinda sorta his latest—it was published nearly a decade ago in Nigeria) showed up in the mail earlier this week. I read the first fifty pages yesterday (about a third of this short book). Thief reads like a memoir-essay, its reportorial style engaged and critical but at times obliquely distant. Our unnamed narrator (surely an iteration of Cole himself) returns “home” to Lagos after fifteen years in New York. Interspersed are Cole’s black and white photographs (echoes of Sebald). Full review to come; for now, publisher Random Houses’ blurb:

A young Nigerian living in New York City goes home to Lagos for a short visit, finding a city both familiar and strange. In a city dense with story, the unnamed narrator moves through a mosaic of life, hoping to find inspiration for his own. He witnesses the “yahoo yahoo” diligently perpetrating email frauds from an Internet café, longs after a mysterious woman reading on a public bus who disembarks and disappears into a bookless crowd, and recalls the tragic fate of an eleven-year-old boy accused of stealing at a local market.

Along the way, the man reconnects with old friends, a former girlfriend, and extended family, taps into the energies of Lagos life—creative, malevolent, ambiguous—and slowly begins to reconcile the profound changes that have taken place in his country and the truth about himself.

In spare, precise prose that sees humanity everywhere, interwoven with original photos by the author, Every Day Is for the Thief—originally published in Nigeria in 2007—is a wholly original work of fiction. This revised and updated edition is the first version of this unique book to be made available outside Africa. You’ve never read a book like Every Day Is for the Thief because no one writes like Teju Cole.

“Spring” — William Carlos Williams

Humpty Dumpty — John Wesley

I Review (Version #10786 of) Nanni Balestrini’s Novel Tristano

Let’s start with some facts:

Nanni Balestrini originally composed Tristano in the 1960s with the aid of an algorithm supplied to an IBM computer.

There are ten chapters in the novel.

Each chapter is comprised of twenty paragraphs.

Balestrini’s algorithm shuffles fifteen of those paragraphs within each chapter.

There are thus 109,027,350,432,000 possible versions of Tristano.

Tristano was published in 1966 by the Italian press Feltrinelli, but in only one of those 109,027,350,432,000 possible versions.

Now, Verso Books has published 4,000 different versions of Tristano in English.

They sent me #10786 to review.

Maybe a few more facts, and then some opinions—and citations from the novel—no?

Umberto Eco spends the first five pages of his six page introduction to Tristano situating Balestrini’s project in its proper literary-historical context. (He names some names: Pascal, Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, Christopher Clavius, Pierre Guldin, Mersenne, Leibniz, Borges, Queneau, Mallarmé, Manzoni, Joyce. There is no mention of Cortázar’s Hopscotch or Bantam’s Choose Your Own Adventure series).

Mike Harakis translated Tristano into English.

Harakis preserves Balestrini’s spare (and often confusing) style of punctuation.

The book is exactly 120 pages.

In his contemporary “Note on the Text” of Tristano, Balestrini says that the book is “an ironic homage to the archetype of the love story.”

The title of course alludes to the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

In his note, Balestrini uses the term “experiment” at least three times, suggesting that “to experiment with a new way of conceiving literature and novels” can make it more “possible to represent effectively the complexities and unpredictability of contemporary reality.”

Balestrini’s 2004 novel Sandokan is in my estimation one of the finest books of the past decade: A poetic examination of criminal brutality told in a bold voice, its syntactical experiments not experiments at all, but rather the base of a strong, strange tone that perfectly synthesizes plot and voice.

Okay. Opinions and citations:

In chapter 2 of my edition of Tristano—on page 19 of version #10786—we get a paragraph that begins: “To be one-sided means not to look at problems all-sidedly.”

Does Tristano, through its formal, discursive, algorithmic structure seek to approach an all-sided perspective? Significantly, we can’t be sure who says the line. There are two characters, male and female, both named C (an algebraic variable?).

There seems to be an argument here, an investigation. A crime, a love affair. But Tristano is a dialectic without synthesis. Or maybe that failure is mine. Maybe I’ve failed as the reader. Neglected my part. “Treat life as if it were a game,” we’re told in the aforementioned paragraph (page 19 of version #10786, if you’re keeping score). Or maybe we’re not told. Maybe C is telling C to treat life as a game (and not just telling the reader), but the context is not (cannot) be clear.

But again, that’s probably maybe almost certainly but okay maybe not quite the point of Tristano. From paragraph 18 of chapter 6 (page 71 of version #10786): “First of all one must have a fairly clear idea of the content of the text.” And a few lines down: “Her story weaves and unweaves like the tapestry she was working on.” And: “It’s the unconditional loss of language that starts.” And: “It might never have an end.” Freeing these lines from the sentences around them ironically stabilizes them.

Tristano isn’t just line after line of Postmodernism 101 though. There is actual imagery here, content. In fairness, let me share entire paragraph (from page 69 of version #10786):

In the internal part of the cave along with an abundance of Pleistocene fauna a human Neanderthaloid tooth was recovered. You’ve already told me this story. The cave is divided into two levels one upper and one lower that host a subterranean lake which can be visited by boat. It might even be another story. They had warned him it wouldn’t be a walk in the park. Inside you can go down into a great cavern in the centre of which there is a rock surmounted by a giant stalagmite. We’ll stay and look for another thirty seconds then we’ll leave. All the stories are different one from the other. On returning he found that C had bought herself a new blue silk dress. C remained standing while he explained to her how it had gone. She ran a finger over his lips to wipe the lipstick off them. I have to go. It’s still early. I’ll be away all day perhaps tomorrow too. He gave her a long kiss on the lips.

This paragraph is maybe almost kind of sort of a synecdoche of the entire book—sentences that seem to belong to other paragraphs, story threads that seem part of another tapestry. Let us pull a thread from another paragraph, another chapter (chapter 9, paragaph 8, page 102 of of version #10786):

All imaginable pathways of the line that represents a direct connexion to the objective are equally impracticable and no adjustment of the shape of the body to the spatial forms of the surrounding objects can allow the objective to be reached.

Do you believe that? Did Balestrini? Or did it just allow him a neat little piece of rhetoric to gel with the concept of his experiment? The verbal force, dexterity, and dare I claim truth of Sandokan, composed a few decades later, suggests that yes, language can be shaped to mean.

And this, I think, is the big failure of Tristano—it’s a text afraid to mean, to even take a shot at meaning. Content to be simply an experiment, its sections adding up to nothing more than the suggestion that its sections could never add up to anything, Tristano offers little beyond its concept and a few observations on storytelling that dwell on paralysis instead of freedom. The whole experiment strikes me as the set up for a joke played on the reader: Look at all this possibility, look at all these iterations—and what’s at the core? Nothing.

I hate to end on such a negative note. I’m thankful that Verso published Tristano, which I think shows courage as well as a commitment to literature that you just aren’t going to see from a corporate house. I’m thankful that I got to read (version #10786 of) Tristano, and I plan to order his novel The Unseen via my local bookstore. The expectations that I brought to the book were huge: Loved the concept, loved the last book I’d read by the author—and I want to read more by the author. Indeed, it’s entirely possible that I failed Tristano’s experiment. But I would’ve been happier to learn something or feel something from that failure other than disappointment.

Ten Notes from Hawthorne’s Note-Books

- On being transported to strange scenes, we feel as if all were unreal. This is but the perception of the true unreality of earthly things, made evident by the want of congruity between ourselves and them. By and by we become mutually adapted, and the perception is lost.

- An old looking-glass. Somebody finds out the secret of making all the images that have been reflected in it pass back again across its surface.

- Our Indian races having reared no monuments, like the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians, when they have disappeared from the earth their history will appear a fable, and they misty phantoms.

- A woman to sympathize with all emotions, but to have none of her own.

- A portrait of a person in New England to be recognized as of the same person represented by a portrait in Old England. Having distinguished himself there, he had suddenly vanished, and had never been heard of till he was thus discovered to be identical with a distinguished man in New England.

- Men of cold passions have quick eyes.

- A virtuous but giddy girl to attempt to play a trick on a man. He sees what she is about, and contrives matters so that she throws herself completely into his power, and is ruined,–all in jest.

- A letter, written a century or more ago, but which has never yet been unsealed.

- A partially insane man to believe himself the Provincial Governor or other great official of Massachusetts. The scene might be the Province House.

- A dreadful secret to be communicated to several people of various characters,–grave or gay, and they all to become insane, according to their characters, by the influence of the secret.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

Kenneth Patchen (Book Acquired, 3.07.2014)