PREVIOUSLY:

Introductions + stories 1956-1959

IN THIS RIFF:

Stories published in 1961:

“Studio 5, The Stars”

“Deep End”

“The Overloaded Man”

“Mr. F Is Mr. F”

“Billennium”

“The Gentle Assassin”

1. “Studio 5, The Stars” (1961)

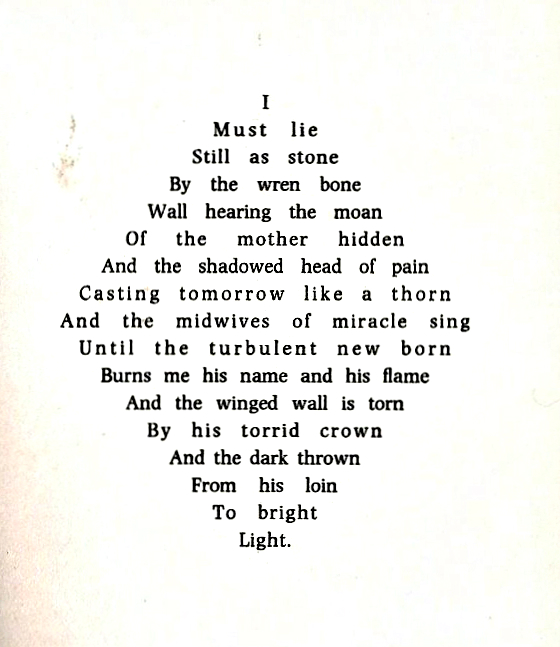

“Studio 5, The Stars” takes poetry as its subject and is the first story in The Complete Short Stories to focus on writing. Ballard’s tales usually concern some aspect of art, but up until now he’s been mainly concerned with music (and to a lesser extent visual art).

“Studio 5, The Stars” is the third tale in the collection set in “the crazy season at Vermilion Sands.” Our narrator is the editor of “Wave IX, an avant–garde poetry review.” Ballard constructs his story around the conceit that writing poetry has become (quite literally) a soulless, mechanical activity. Our narrator explains to his interlocutor:

I used to write a fair amount myself years ago, but the impulse faded as soon as I could afford a VT set. In the old days a poet had to sacrifice himself in order to master his medium. Now that technical mastery is simply a question of pushing a button, selecting metre, rhyme, assonance on a dial, there’s no need for sacrifice, no ideal to invent to make the sacrifice worthwhile –

Our narrator’s interlocutor is Aurora Day, a femme fatale who either is or believes she is “Melander,” an archetypal muse of poetry (invented by Ballard, of course). Aurora is distraught over the state of poetry. And no wonder. Verse is now composed on a “VT set”:

‘Hold on,’ I told him. I was pasting down one of the Xero’s satirical pastiches of Rupert Brooke and was six lines short. I handed Tony the master tape and he played it into the IBM, set the metre, rhyme scheme, verbal pairs, and then switched on, waited for the tape to chunter out of the delivery head, tore off six lines and passed them back to me. I didn’t even need to read them.

The story can perhaps be condensed into this wonderful line:

Fifty years ago a few people wrote poetry, but no one read it. Now no one writes it either. The VT set merely simplifies the whole process.

In his introduction to the collection, Ballard insisted that he “was interested in the real future” he saw coming, not an invented one. The notion of machines recording art that no one will bother to read seems particularly resonant today. Reading “Studio 5, The Stars,” I was reminded of Kenneth Goldsmith’s recent “art” project/stunt of printing the internet. There’s also something in the VT that recalls Slavoj Žižek’s riff on VCRs, machines recording and storing films that the viewer will never actually watch.

“Studio 5, The Stars” takes aim at a commercial culture that pays lip service to the high ideals of “culture” while simultaneously insuring that “culture” can be consumed at no sacrifice—no work—on the part of the consumer.

2. “Deep End” (1961)

Humanity migrates to Mars after sucking all the resources from the Earth. “Deep End” is a brief tale (and another in the collection to feature one of Ballard’s signature images, the drained swimming pool). An ecological dystopia, “Deep End” feels like a sketch for something bigger—but it gains power from its brevity, and Ballard is content to focus his energies on just a few characters and one core idea here. The restraint pays off in the story’s nihilistic punchline, which I won’t spoil here.

3. “The Overloaded Man” (1961)

“Faulkner was slowly going insane” is an excellent way to begin a story, and Ballard delivers on his promise. Faulkner can no longer stand his cookie-cutter life in a cookie-cutter house. To alleviate his alienation from modern living, Faulkner builds a strange defense mechanism—he learns that he can dissociate himself from objective reality:

Steadily, object by object, he began to switch off the world around him. The houses opposite went first. The white masses of the roofs and balconies he resolved quickly into flat rectangles, the lines of windows into small squares of colour like the grids in a Mondrian abstract. The sky was a blank field of blue. In the distance an aircraft moved across it, engines hammering. Carefully Faulkner repressed the identity of the image, then watched the slim silver dart move slowly away like a vanishing fragment from a cartoon dream.

How to overcome alienation in a Ballardian world? Even more radical alienation. While “The Overloaded Man” points to a nihilism even bleaker than that in “Deep End,” it also demonstrates a marked improvement in Ballard’s writing from the earlier stories in the collection. We see Ballard controlling metaphor and imagery with a much stronger command than in the first half-dozen stories of his career. He sets out his poor hero’s mechanized domestic milieu in one savage line:

Her kiss was quick and functional, like the automatic peck of some huge bottle–topping machine.

There’s perhaps a slight streak of misogyny in “The Overloaded Man,” which at its core might be described as a story of a man whose nagging wife depresses him. Any ambivalence or fear of the female body that we’ve seen so far in the collection—in the dull, bothersome wives of “The Overloaded Man” or “Escapement,” or the powerful femme fatales of “Prima Belladonna,” “Venus Smiles,” or “Studio 5, The Stars”—any such hint burns vividly in the next story in the collection.

4. “Mr. F Is Mr. F” (1961)

“Mr. F Is Mr. F” tells the story of Charles Freeman and his pregnant wife, a woman presented with an almost-bovine simplicity that quickly escalates into horror. Charles Freeman grows younger and younger until he’s eventually absorbed into the maternal body.

The story is so nakedly Freudian that even its narrator has no problem spelling out the subtext for readers slow on the uptake:

He was forty when he married Elizabeth, two or three years her junior, and had assumed unconsciously that he was too old to become a parent, particularly as he had deliberately selected Elizabeth as an ideal mother–substitute, and saw himself as her child rather than as her parental partner.

“Mr. F Is Mr. F” is, by my count, the first Ballard story that explicitly takes the human body as its major object of study. Time, of course, is the ever-present grand theme of Ballard’s work, but up until now he’s concentrated his attention on time’s impact on geology, psychology, and culture—but not the human body. The story doesn’t so much analyze a fear of the maternal body so much as it uses that trope to generate fear and abject disgust.

There’s a teleological neatness to “Mr. F Is Mr. F” that one senses Ballard was trying to pull off in some of his stories of the late 1950s, but couldn’t quite achieve. His chops are stronger here, and, paradoxically perhaps, less slavishly beholden to Edgar Allen Poe, he actually turns in a tale worthy of his hero.

5. “Billennium” (1961)

“Billennium” sees Ballard returning to the themes of overpopulation and overcrowding that he began exploring in 1957’s “The Concentration City.” The world Ballard imagines is horrifying—moreso because his representation of it is in some ways so terribly banal:

As for the streets, traffic had long since ceased to move about them. Apart from a few hours before dawn when only the sidewalks were crowded, every thoroughfare was always packed with a shuffling mob of pedestrians, perforce ignoring the countless ‘Keep Left’ signs suspended over their heads, wrestling past each other on their way to home and office, their clothes dusty and shapeless. Often ‘locks’ would occur when a huge crowd at a street junction became immovably jammed. Sometimes these locks would last for days. Two years earlier Ward had been caught in one outside the stadium, for over forty–eight hours was trapped in a gigantic pedestrian jam containing over 20,000 people, fed by the crowds leaving the stadium on one side and those approaching it on the other. An entire square mile of the local neighbourhood had been paralysed, and he vividly remembered the nightmare of swaying helplessly on his feet as the jam shifted and heaved, terrified of losing his balance and being trampled underfoot. When the police had finally sealed off the stadium and dispersed the jam he had gone back to his cubicle and slept for a week, his body blue with bruises.

“Billennium,” like many of the stories of 1961, benefits from Ballard’s increasing restraint. While “The Concentration City” is overfreighted with too many ideas to succeed as a perfect short story, Ballard maintains a focus in “Billennium” that pays off. And if the story is predictable—and predictably nihilistic—it nevertheless offers a chilling vision of the future that could very likely come to pass.

6. “The Gentle Assassin” (1961)

“The Gentle Assassin” is basically Ballard’s mechanism to discuss the so-called “Grandfather Paradox,” a time-travel conundrum of causality and intent. The tale is as neat and tidy as “Mr. F,” but it also showcases a patience and restraint; Ballard slowly builds an ominous, ironic atmosphere before executing his narrative trick. “The Gentle Assassin” isn’t particularly memorable, and there are dozens and dozens of versions of it to be found throughout sci-fi. Still, we see here–and in the other stories of 1961—that Ballard is more confident and able in his prose and plotting.

7. On the horizon:

We’re still a long way out from the formal experimentation of “1966’s The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race” or 1968’s “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan,” but Ballard’s pulp fiction gets tighter—and weirder—as we go.