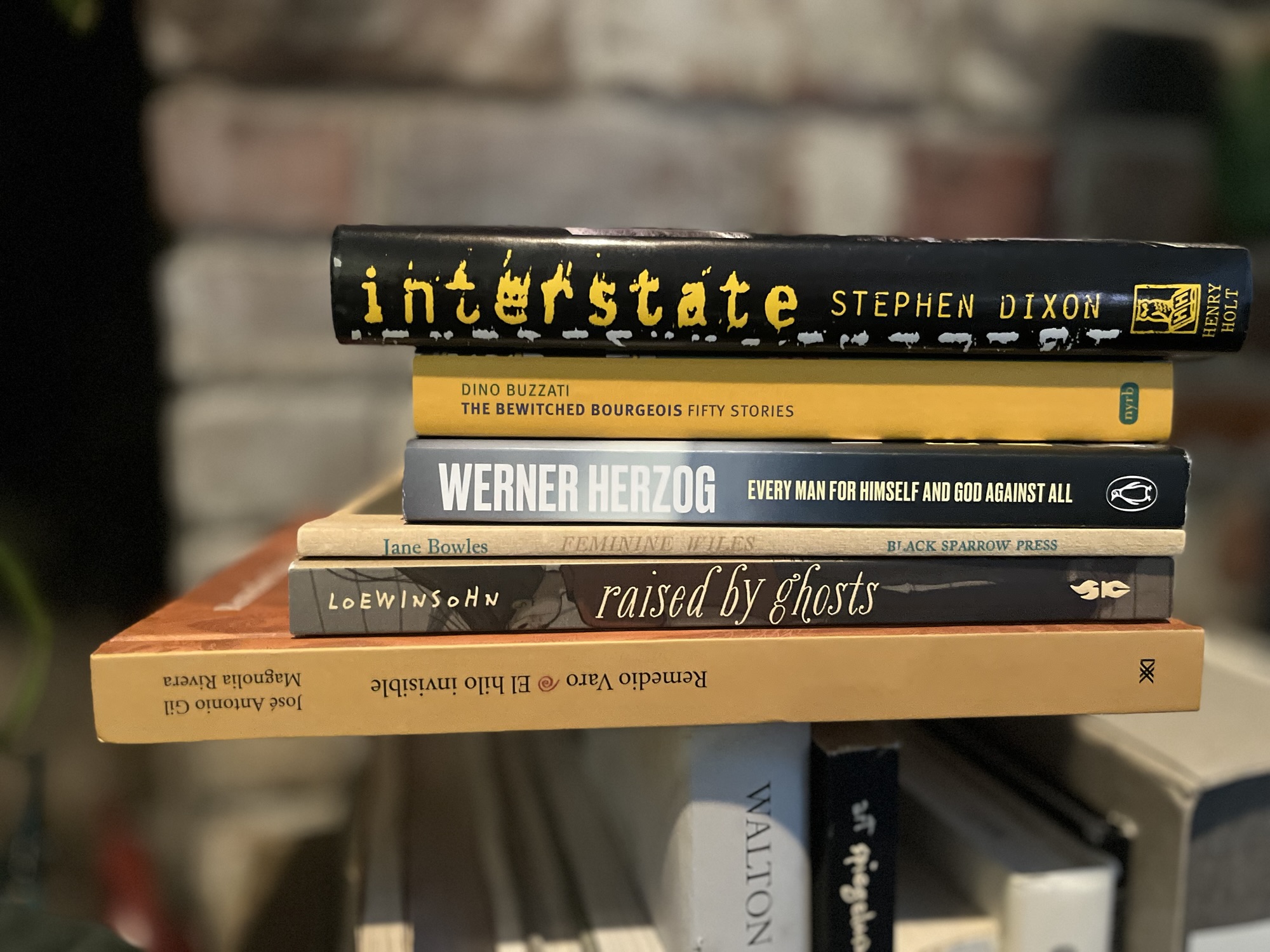

Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Notes on Chapters 21-23 | Phantom gearbox.

Chapter 24: Another fairly long chapter for Shadow Ticket. I’ve been over-summarizing in these notes, and maybe I’ll keep over-summarizing — at this point doing these notes has been my second reading of Shadow Ticket. I would say though, that we’ve reached a point well beyond the novel’s quick change glamour, its bilocative split — or its bait n’ switch, if you feel that way. The novel initially presents as a hardboiled noir send-up in the dark American Heartland only to pivot (or bilocate, to misapporpriate a term from Against the Day) to Central Europe where there’s preparation for a war on (moron). Hero Hicks fades, just a little, in the background; a larger cast steps up.

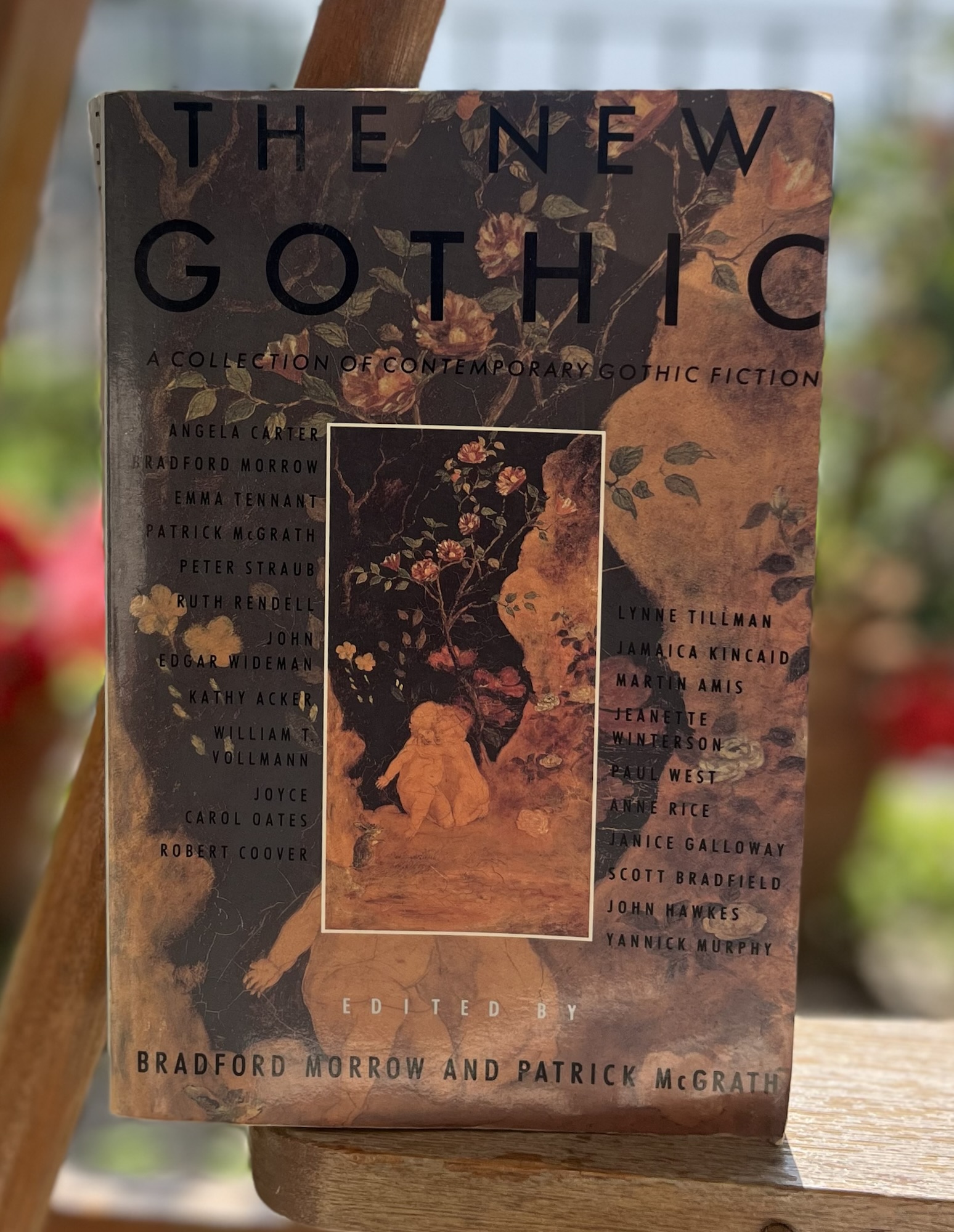

But Hicks is still the heart of Ch. 24, which begins at Egon Praediger’s office in Budapest, where the ICPC detective is snorting soup spoonfuls of cocaine while ranting about his inability to catch Bruno Airmont. Egon fears he’s wasting his talent “not on an evil genius but on an evil moron, dangerous not for his intellect, what there may be of it, but for the power that his ill-deserved wealth allows him to exert, which his admirers pretend is will, though it never amounts to more than the stubbornness of a child.” Oh man–wonder if that sounds like any evil moron of recent vintage? Egon would rather face off against a worthy villain, a “Dr. Mabuse or Fu Manchu,” references again underlining Shadow Ticket’s lurid pop Goth bona fides.

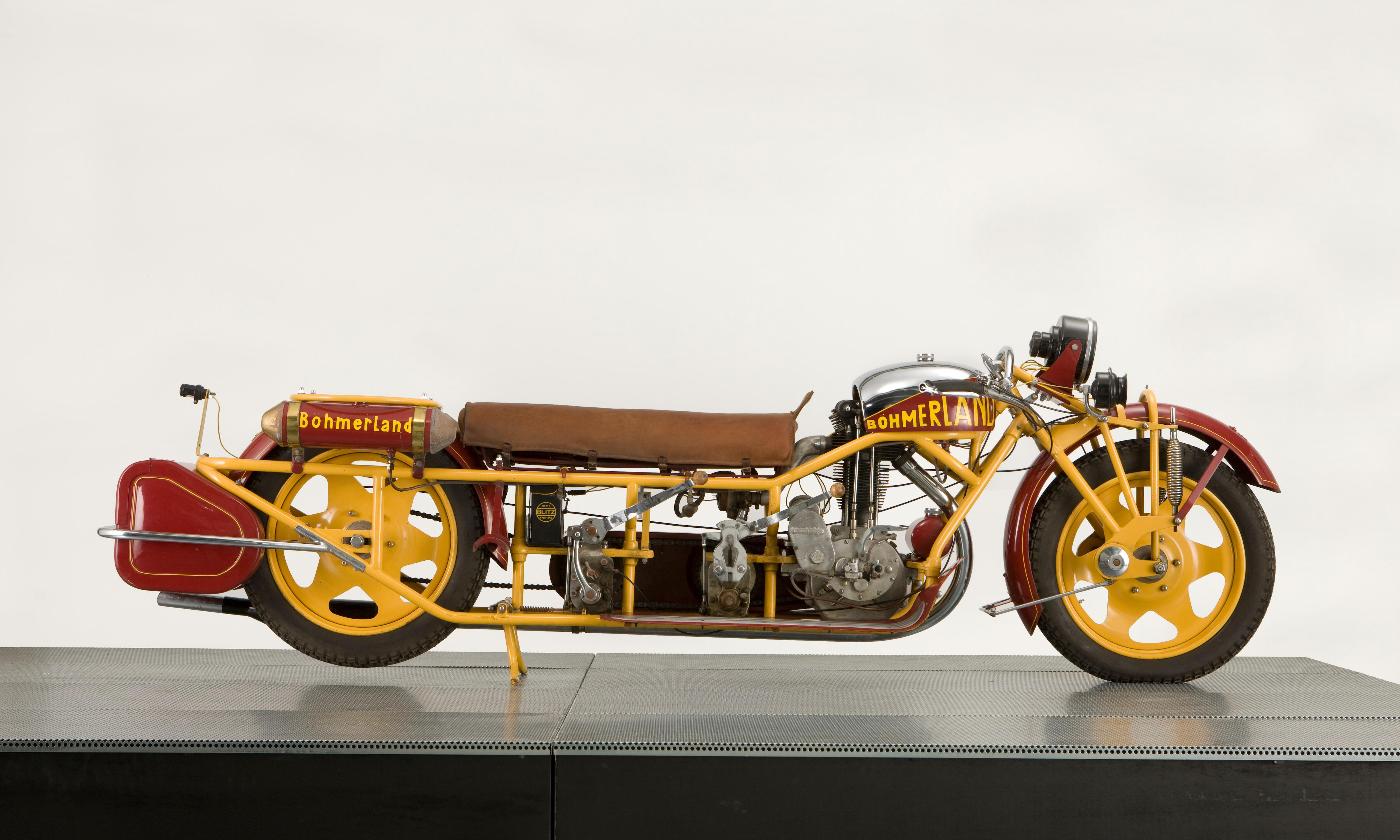

Hicks then runs into Terike, “just emerging from her latest run-in with the authorities over her motorcycle, a 500 cc Guzzi Sport 15″ — which more on this transport later. On the way to the bike, Hicks finds that he has somehow “percolated through“ Terike, who has performed some kind of metaphysical quick change. He apports, I guess.

For Terike, the Guzzista “is a metaphysical critter. We know, the way you’d say a cowboy knows, that there’s a fierce living soul here that we have to deal with.” As we should expect now in Ole Central Europe, this bike is spooky, and Terike is a superhero on it: “she can go straight up the sides of walls, pass through walls, ride upside down on the overheads, cross moving water, jump ditches, barricades, urban chasms one rooftop to the next, office-building corridors to native-quarter alleyways quicker than a wink.”

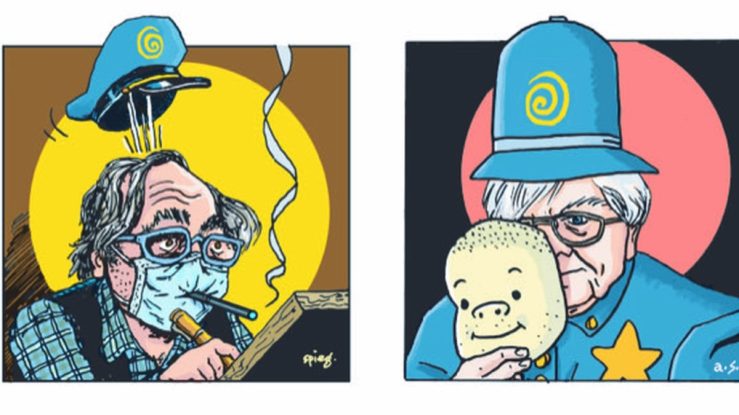

Hicks rides along in the sidecar. (A bit later we’ll see a charming pig, a spirit animal, really, riding sidecar–perhaps there’s a link between Hicks and Pynchon’s other pigmen, like Seaman Bodine or Tyrone Slothrop (or the unfortunate Major Marvy.) Their mission: deliver a batch of experimental vacuum tubes “specially designed for the theremin” to “Club Hypotenuse,” a “cheerfully neon-lit” venue featuring a rotating dance floor and “not just one soloist on theremin but a half dozen, each expensively gowned tomato with more or less identical platinum bobs, waving their hands at these units and pulling music out of some deep invisibility, swooping one note to the next, hitting each one with pitch as perfect, Terike assures him, as the instrument’s reigning queen, Clara Rockmore. The joint effect of these six virtuoso cuties all going at once in close harmony is strangely symphonic.”

(Forgive me if I let the quote linger too long, the image is just too lovely.)

At Club Hypotenuse we get a bit of background on Terike, her rejection of her bourgeoisie upbringing, and recent Hungarian political struggles, before meeting yet another character, freelance foreign correspondent Slide Gearheart (he uses the alias “Judge Crater” at the bar. We last heard the name back in Ch. 18, but Crater, icon of the disappearing act, will pop up again). Slide lets Hicks in on a lead he has to cheese heiress Daphne Airmont’s whereabouts; he also gives our P.I. some advice about (not) fitting in to Hungary: “…best stick to English and there’s a chance they’ll take you for an idiot and leave you alone. It might help if you could also pretend now and then to hear voices they don’t. Idiots get respect out here, they’re believed to be in touch with invisible forces.”

But Slide’s bigger note for Hicks is a soft warning to prepare him for the reality that you can never really go home.

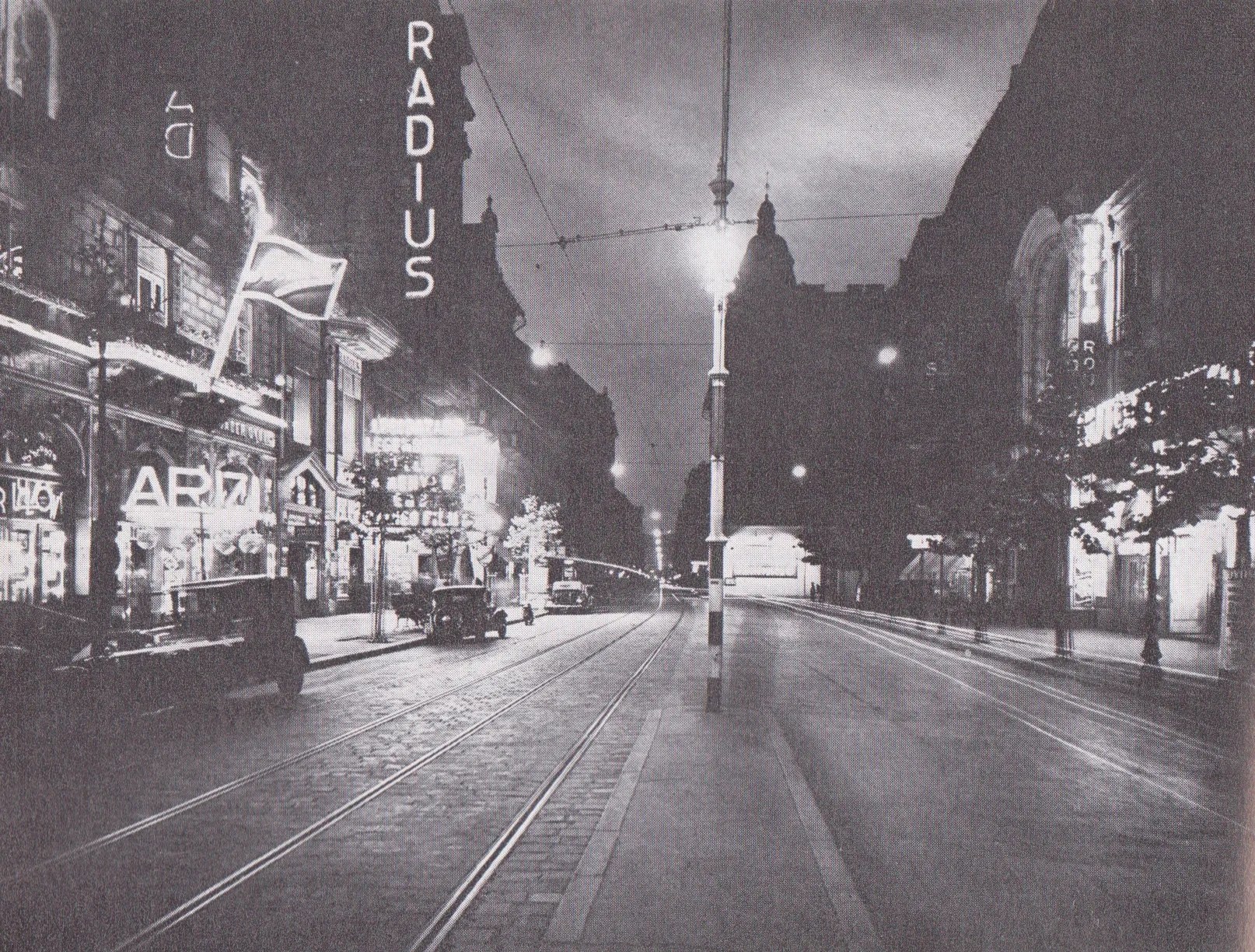

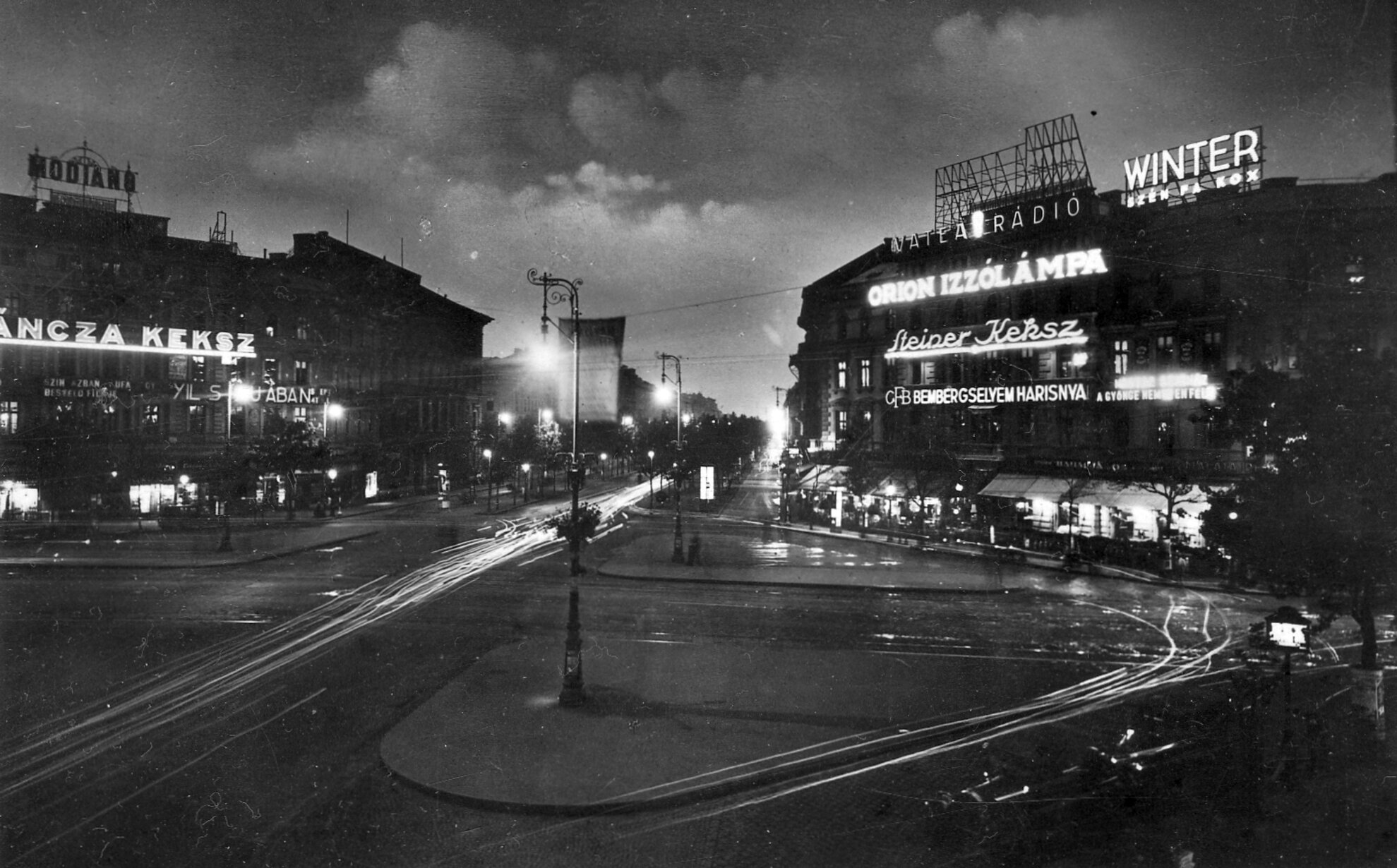

Chapter 25: “Things pick up a day or two later when Slide reports that Daphne has been sighted at the Tropikus nightclub, in Nagymező utca, the Broadway of Budapest.” (This is I suppose the inspiration for the use of the photograph of Nagymező Street used on the cover of the first edition of Shadow Ticket.)

Daphne sings a song and then she and Hicks dance together.

So–I have really neglected Shadow Ticket as a song and dance routine. I think if you’ve read Pynchon you’d expect it; it’s a bit more prevalent here, the singing and dancing, in Shadow Ticket I mean, then in some of the other novels, but it’s certainly what you’d expect. The songs probably deserve their own whole blog or something to deal with (which I will never do); the dancing — well the dancing — I think something I should’ve highlighted much earlier is that Hicks is a really good dancer. Like fucking excellent. He’s a magician who goes into “one of those hoofer’s trances” in the previous chapter while dancing with Terike to the theremin orchestra. That notation — of the trance state — is given for various characters in Shadow Ticket who achieve a kind of short-term perfection outside the physical realm. (It’s the drummer Pancho Caramba (and like, Pynchon, c’mon man, that’s too much, name wise) — it’s the drummer Pancho Caramba in Ch. 25 who goes “into this kind of trance” at his drum kit, enchanting his audience.)

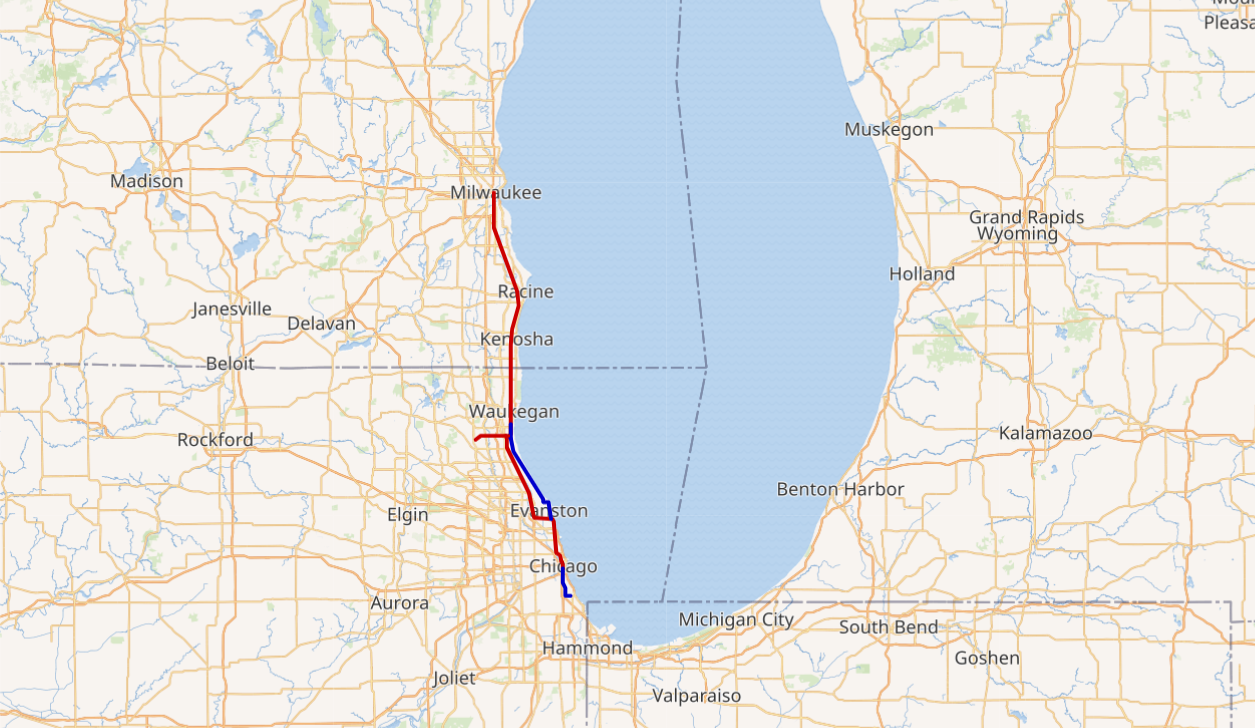

Most of the chapter is the dance and the dance-within-the-dance between Hicks and Daphne. There are Gothic-tinged allusions to their past in Wisconsin–his saving her from the “North Shore Zombie Two-Step” of forced psychiatric hospitalization, incurring a “Chippewa hoodoo” debt as her caretaker in perpetual.

We also start to get Daphne’s backstory with Hop Wingdale, the jazz clarinetist she left home for. She’s followed Hop and his band the Klezmopolitans around Europe, but is worried that the ill-fated lovers “need to relocate before it’s all Storm Trooper chorales and three-note harmony.” Daphne again underlines Shadow Ticket’s departure point — a big ugly change is gonna come. Hop is (rightfully) worried about Papa “Bruno’s invisible hand…” though. “Awkwardly enough,” he tells Daphne, “it turns out more of your life than you think is being run on the Q.T. by none other” but her pops.

The phrase “on the Q.T.” — meaning quiet (or “on the quiet tip,” as I thought way back as a teen encountering it) — shows up a few times in Shadow Ticket. It’s phonetically doubled in the word cutie, which shows up more than a few times in Shadow Ticket.

Chapter 26: Another longish section by Shadow Ticket standards, and less breezy than the novel as a whole.

There’s a lot of Daphne-Hicks and Daphne-Hop stuff here — more bilocations, maybe? — in any case, our boy Hicks gets himself more wrapped up than he intended to. After Daphne urges him to help hunt down Hop, who’s kinda sorta left her, he reminds himself of his mantra “No More Matrimonials! Ever!”

By the end of the chapter our American idiot is wondering if “wouldn’t it be a nice turnaround to bring some couple back together again, put the matrimony back in ‘matrimonial’ for a change, instead of divorce lawyers into speedsters and limousines.” Here, I couldn’t help but think of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film revision to Pynchon’s novel Inherent Vice; PTA ties a neater bow on the narrative by letting its lead P.I. Doc Sportello restore the marriage of musician Coy Harlingen.

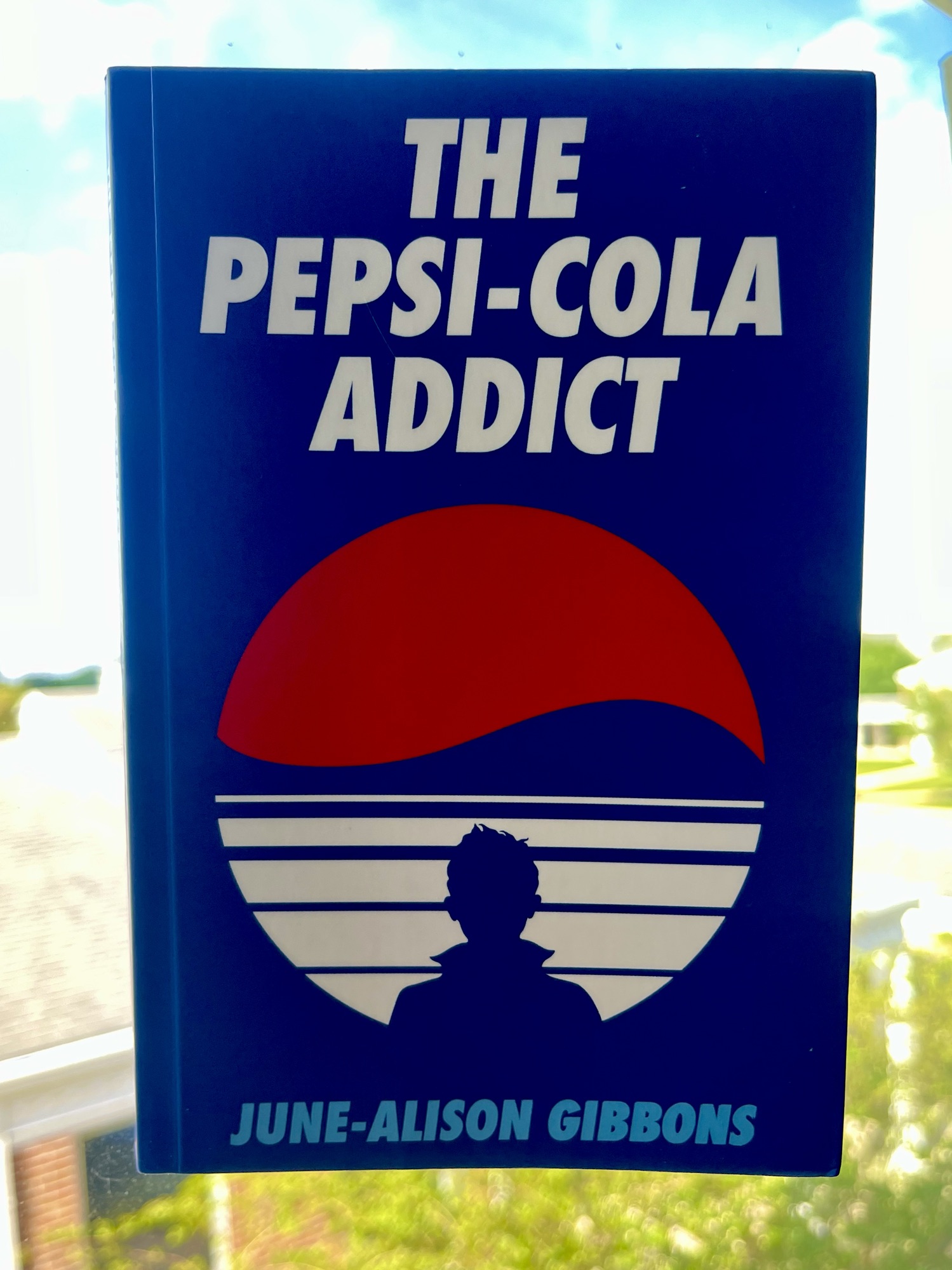

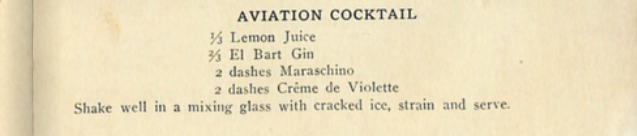

Anyway, we get Daphne and Hop’s origin story: “Talk about meeting cute. You’d think she’d have known better by then. It was in Chicago a few years back, still deep in her teen playgirl phase.” General gunplay shatters Daphne’s double aviation cocktail. She’s smitten with his woodwind serenades.

This chapter is chocked full of motifs and mottoes we’d expect from Shadow Ticket in particular at this point and Pynchon in general: invisibility, inconvenience, Judge Crater, “Who killed vaudeville?,” etc. It’s also pretty horny, with Hicks and Daphne finally consummating their meet cute from years gone by. Sorry if I’m breezing through.

I’m more interested in a specific exchange.

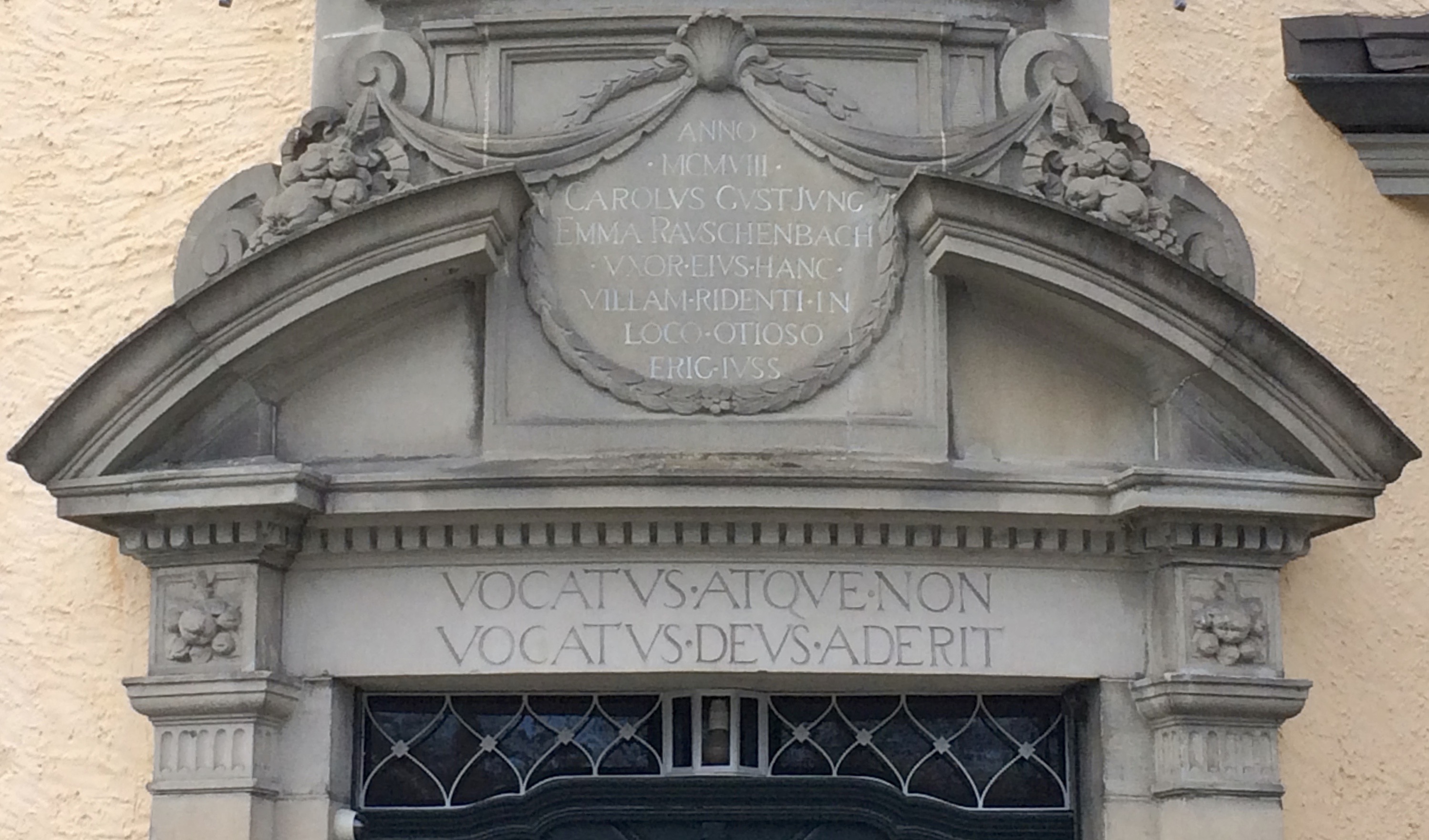

Daphne hips Hicks to something she saw “once, in one of these mental fix-it shops I kept getting sent to, up on the office wall was a motto of Carl Jung—Vocatus atque non vocatus deus aderit. I said what’s this my Latin’s a little rusty, he sez that’s called or not called, the god will come.”

The end of Ch. 23, at least in my guess, seemed to obliquely reference Jung’s Answer to Job, with the narrator suggesting that a trinity can only truly operate as a whole in the form of a stealth quatro — it’s phantom fourth piece balancing out the visible trio in the foreground. The reference to Jung here is not oblique but direct and maybe I will do something more direct with it down the line.

Of course the thing that comes to save Daphne isn’t “the god” but that Big Gorilla Hicks. He notes that, “Your old pals from the rez think it’s spoze to be a critter” who shows up to save the day. In a moment of vulnerability that I take to be sincere, Daphne asks Hicks if he didn’t think that she might actually be insane and should be returned to the hospital and not set free. His reply is a repetition of one of the novel’s several theses: “You were on the run, that was enough.”

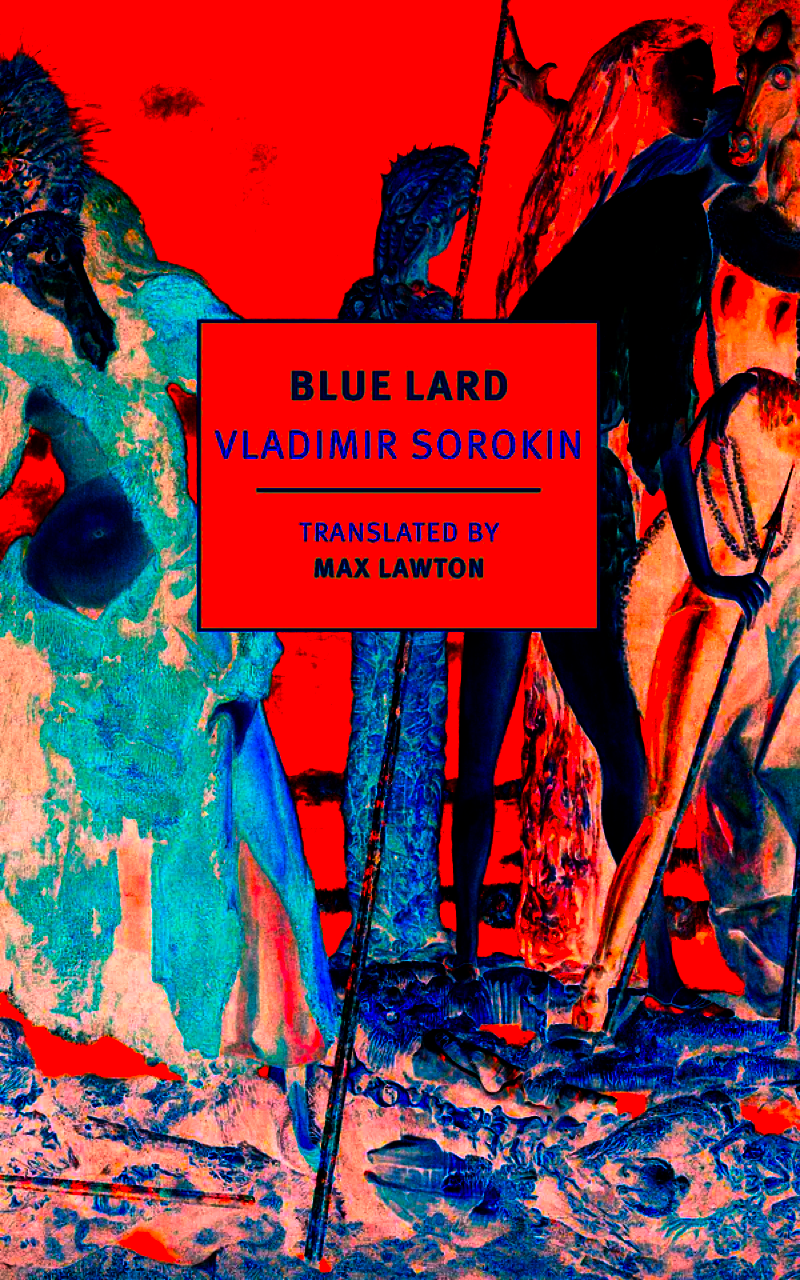

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…