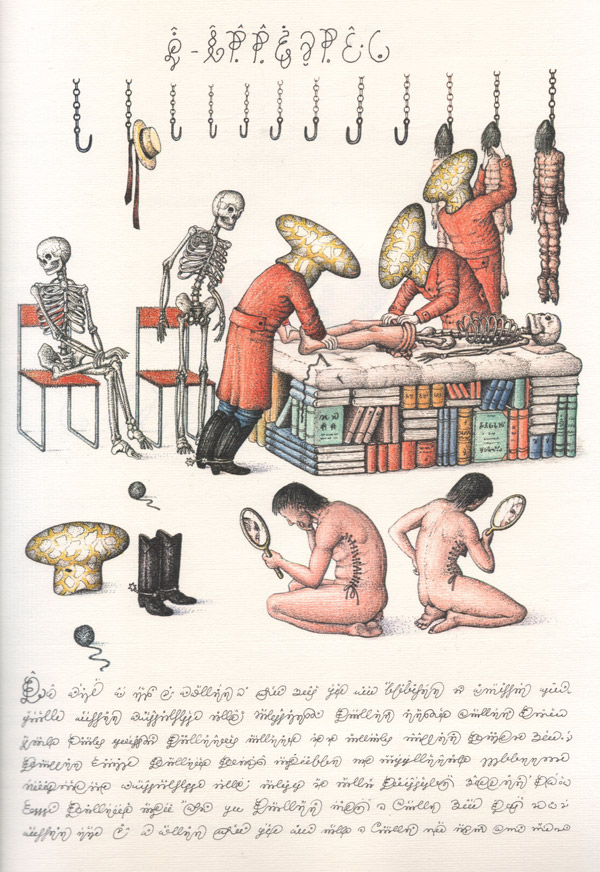

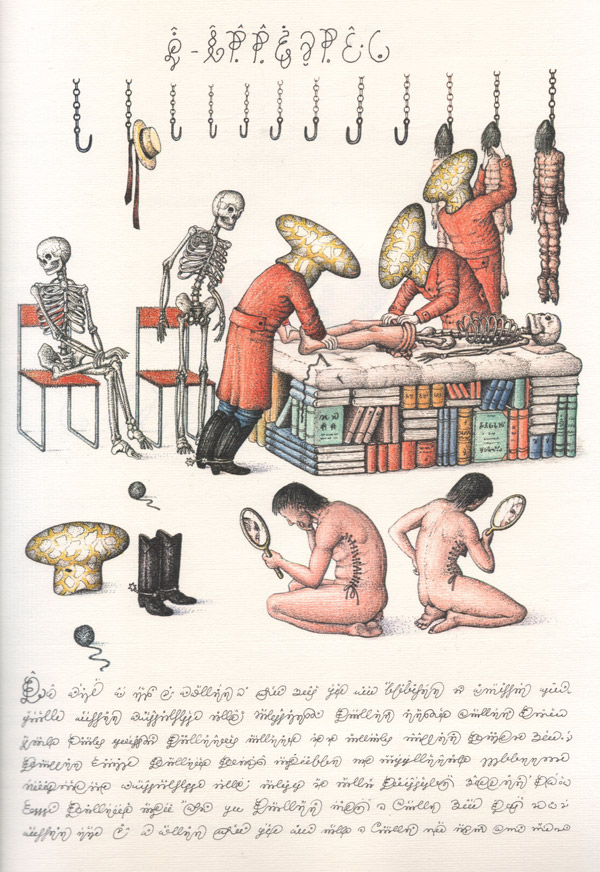

Images from Luigi Serafini’s surreal cryptoencyclopedia, Codex Seraphinianus. Learn more by reading Justin Taylor’s essay from the May 2007 issue of The Believer.

Images from Luigi Serafini’s surreal cryptoencyclopedia, Codex Seraphinianus. Learn more by reading Justin Taylor’s essay from the May 2007 issue of The Believer.

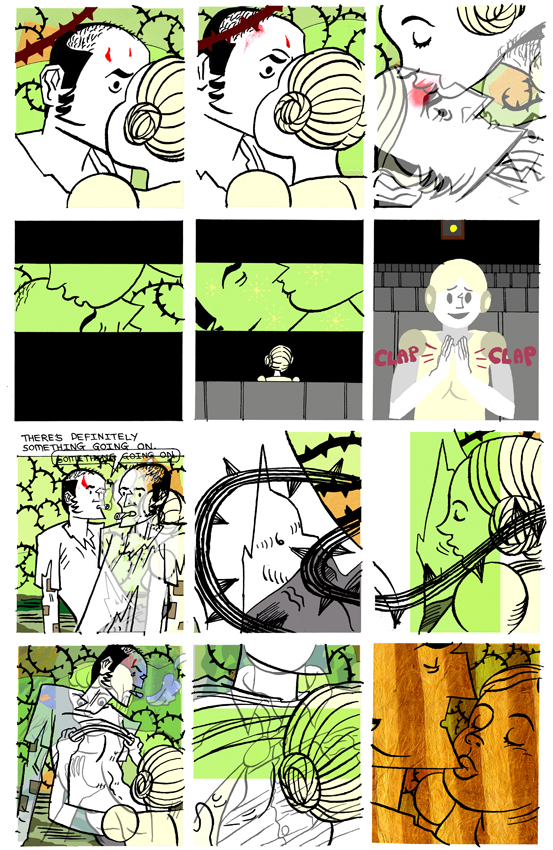

Jacksonville Public Library’s Zine Collection is one of the first–and largest– such collections in the Southeastern United States. Librarian and collection archivist Josh Jubinsky was kind enough to talk to Biblioklept about the collection, the essence of punk, the future of zines in an increasingly technologically-mediated world, and the million-fart bill. We corresponded via email, although we could have done the interview in person easily–in full disclosure, I should mention that Josh lives down the street from Biblioklept World Headquarters.

Jacksonville Public Library’s Zine Collection is one of the first–and largest– such collections in the Southeastern United States. Librarian and collection archivist Josh Jubinsky was kind enough to talk to Biblioklept about the collection, the essence of punk, the future of zines in an increasingly technologically-mediated world, and the million-fart bill. We corresponded via email, although we could have done the interview in person easily–in full disclosure, I should mention that Josh lives down the street from Biblioklept World Headquarters.

Biblioklept: What is a zine?

Josh Jubinsky: A zine is a self-published pamphlet that ranges in format, size and topic. Although zines are clearly something dating back to the chapbooks of beat poets, to early science fiction fanzines and writings, to the 1960’s super hero comic zines such as Alter Ego which help spearhead a comics industry focusing more of masked avengers than horror and romance stories – my involvement with them has been only over the last 10 or so years and from a predominantly punk background. Whether the zines are music fanzines, literary journalistic diatribe, or DIY projects of a particular focus they are grounded largely in a punk music subculture and involve some sort of activism or simply an independent alternative media appeal. Physically speaking, a zine is typically a stack of 8 1/2 x 11 paper folded in half and stapled along the folded edge – although size and format does drastically vary.

B: Tell us a little bit about the Zine Collection at the Jacksonville Library.

JJ: The collection at the library had it’s grand opening party during the October Artwalk of 2009. It was started mostly on donations we had accumulated from my contacts from having a record store and distro [Deadtank distribution — ed.] (the store for 2 years, and the distro about 8.). We’ve gotten some funding from the library that, while it may not be much money compared to many other library activities, it goes a long way when you’re purchasing zines that cost $1-$2 a piece. Everything in the collection circulates, nothing is purely a reference material. As of now we have about 500 zines, and most everything has been checked out at least once. The circulation stats are great considering the size of the collection, averaging around 100 – 150 items a month.

Personally, it’s become a great vehicle for me to branch out into other programming at the library. I work in children’s library so in the past my programming outlets were confined to children’s programming – storytimes, outreaches to schools. I took that and applied my personal tastes and preferences to the job by teaching guitar lessons, doing classes on bike repair and safety, getting a children’s band together and having kids play all the instruments à la Rock Camp. But that sort of personal job molding increases tenfold when you can do programming in the name of the zine collection. The outreaches are to the Harvest of Hope Festival, to Cinema Sounds, to punk rock shows in warehouses. The programs are bands playing and zine authors reading or being part of a panel discussion. And that focuses back on my being in the children’s department. I started and now run a weekly creative writing and comic drawing class for kids called Zine Machine. The projects the kids work on get put into a zine that becomes part of the library collection. We’re not just creating library patrons, we’re creating authors.

B: Zine Machine sounds really cool. What are some of the things the kids are writing about?

JJ: The first issue was just completed. It’s writings, collages, comics, etc. from January to April. The writing covers everything from short bios on themselves (with self-portraits of course) to designing a car. Some writing prompts are for basic journal entries, writing a review of a book, movie, or video game, asking things like what sot of super powers they’d like to have and why, describing how they think libraries could be better. . . It’s really interesting to see what kids come up with and how they approach the writing and the comics. The class is for kids ages 8-13, though I can’t seem to say no to the 7 years olds that show up. To talk about the difference between a magazine and a zine and have the kids understand that – to be exposed to what an advertisement is and why they are in magazines – to learn about why zines are important and how hey can do this themselves – it’s all really empowering for anybody, especially young kids. Before these kids even have it ingrained in them that “writing is hard” or “what you do isn’t good enough” or “it’s hard to get published” – they are learning and experiencing the opposite. The next issue won’t be from as long a time period of writing.

We’re focusing all month on a single project of designing a country. They are drawing maps, flags, and currency, making laws and deciding things like the country motto and tree. I am so excited about it. The variations in projects from kid to kid are so vast. The variation is amazingly refreshing – amazingly unique- for someone who’s only been alive for 8 years. Some kids have currency that is all based on roman numerals they look up, and others – the king of the country “Only Boys!” has currency based on farts. Everything from a 5 fart coin to a 1,000,000 fart bill. The class is hilarious and fun.

B: I guess you know you’ve made it when your face is on the million-fart bill.

One of the things I like about zines is that they tend to be the products of a very personal, different perspective; they tend to be obsessive and weird. Do you have any particular favorites from the collection you could highlight for us?

JJ: One that I really enjoyed and I wish I saw more of is A La Maison. It’s a french zine, written in English though. It’s a guide to the city of Lyon, France by some people who live there. Definitely a punk perspective on the city, maybe like a punk travel guide. It goes through the city section by section with what bars, falafel places and record stores are best. And it comes with a CDR of all these bands from Lyon. It’s amazing. The people who put out the zine set up a show for my band [Josh is in about seventy bands –ed.] when we toured Europe. I got the zine for the library when their band came through Florida on tour. Touring with your band selling a zine and CDR for a few bucks, advertising how awesome your town is – it’s amazing. Another favorite of mine is a zine called Snakepit. It’s perfect for the short attention span comic reader. Books compiling the issues focus on an entire year of his life, where every three panels is a day. Some Florida ones I love are America? by Travis Fristoe and Seven Inches to Freedom by Joe Lachut. Travis is just an amazing writer that I can’t recommend enough. Joe’s zine is primarily about music, record collecting in terms of hardcore punk. We have the book version of Zine Yearbook 9; it’s a good “best of” type-thing that helps find what you like.

JJ: One that I really enjoyed and I wish I saw more of is A La Maison. It’s a french zine, written in English though. It’s a guide to the city of Lyon, France by some people who live there. Definitely a punk perspective on the city, maybe like a punk travel guide. It goes through the city section by section with what bars, falafel places and record stores are best. And it comes with a CDR of all these bands from Lyon. It’s amazing. The people who put out the zine set up a show for my band [Josh is in about seventy bands –ed.] when we toured Europe. I got the zine for the library when their band came through Florida on tour. Touring with your band selling a zine and CDR for a few bucks, advertising how awesome your town is – it’s amazing. Another favorite of mine is a zine called Snakepit. It’s perfect for the short attention span comic reader. Books compiling the issues focus on an entire year of his life, where every three panels is a day. Some Florida ones I love are America? by Travis Fristoe and Seven Inches to Freedom by Joe Lachut. Travis is just an amazing writer that I can’t recommend enough. Joe’s zine is primarily about music, record collecting in terms of hardcore punk. We have the book version of Zine Yearbook 9; it’s a good “best of” type-thing that helps find what you like.

B: You bring up punk music, which many people closely associate with zines. What about non-punk zines? Or is zine-making punk in and of itself, despite aesthetics/ideology/taste/style?

JJ: We’re getting into really loaded words here, and I don’t think a conversation about what I think is punk and not punk will be too helpful for anyone. But yes, there are plenty of “non-punk” zines in terms of subject matter. Though to me they almost all seem like something punk – indeed not by musical interest, but an aesthetic appeal or just the fact that you’re doing a zine. People may not identify with being punk in some way, but if you do a zine you have a lot in common with punk. In terms of like doing it yourself, being part of a grassroots publishing world – in part, the medium is the message. I can’t really separate myself from that, although lots of bizarre gray areas exist. Are those little religious pamphlets people leave at the post office punk? Are these zines? That’s people expressing themselves, right? And they are sharing there thoughts at a grassroots level. Essentially, they already have the most published book in the world working for them. Take for example the Zine Machine zine. Nine year old kids aren’t automatically punk for contributing to a zine. But more punk than a kid who didn’t, maybe? It’s a very empowering exercise. It’d definitely be appreciated by anyone I’d consider punk. Does that sound too insular?

The zine collection is definitely helping me to branch out and find zines that aren’t somehow tied to the music scene I’m part of, to find zines besides fanzines, or amazing literary zines that are of course full of punk culture references or that I first got into because I know the author some other way (his or her band, label, meeting them at a show). Being a part of creating this is helping me understand it all more.

B: Why are zines important or meaningful in the age of the blogging? How are zines different than blogs? Is technology bad for zines? What’s the future of zines?

JJ: Maybe this sounds like an overused reason for me (since it’s the same main reason I give when people ask why I have records), but, essentially that zines are tangible. Personally, that tangibility helps me remember them. I can barely tell you what I read online yesterday, but I can tell you about the book or zine I’m reading. You can bring zines along when you go on a tour or go fishing or go to the bathroom or sit in the park – and you don’t have to have an expensive device you must charge to read them. They also exude a sense of time and place. A zine is self-contained, obviously not in literary or musical references, but you can’t get bored with it and click to an updated version. You can’t add it to your blog reader. Like a record, it’s not convenient. It’s romantic. You aren’t jogging while listening to an audio book – you aren’t trying to maximize productivity. You sit, enjoy and get fresh air at the same time.

JJ: Maybe this sounds like an overused reason for me (since it’s the same main reason I give when people ask why I have records), but, essentially that zines are tangible. Personally, that tangibility helps me remember them. I can barely tell you what I read online yesterday, but I can tell you about the book or zine I’m reading. You can bring zines along when you go on a tour or go fishing or go to the bathroom or sit in the park – and you don’t have to have an expensive device you must charge to read them. They also exude a sense of time and place. A zine is self-contained, obviously not in literary or musical references, but you can’t get bored with it and click to an updated version. You can’t add it to your blog reader. Like a record, it’s not convenient. It’s romantic. You aren’t jogging while listening to an audio book – you aren’t trying to maximize productivity. You sit, enjoy and get fresh air at the same time.

The interruptions are minuscule compared to reading something online. Right now as people are reading this I bet they have other windows open – your friend messaging you, some work you need to finish, your email. These readers won’t read this without clicking over to something else. What sort of compromises are we making, as readers, with this convenience? How much are we losing from what we really want to be doing by always trying to do something else in tandem? Technology isn’t bad for zines, it’s just different. Blogs and zines, these have very different cultures around them. You used to mail order zines from a paper catalog or get them at your local record store. Those catalogs are gone. Those stores stay open largely because some kid who doesn’t care about his credit is paying rent on his credit card, or people live in the back room. I’m not saying any of this is good or bad, it’s just different. The idea of convenience is literally changing our landscape. Sometimes it’s more convenient to work around modern day conveniences, and even when it’s not, you want to because it’s what you love. Zines help me relax. I like [love — ed.] your blog and I have one too, but – the internet is so full of crap. It just adds to the rushed feeling of our days. Increasingly days are becoming more and more just a series of errands and obligations. When I want to read something, I don’t want to be in front of the same machine, sitting in the same position, probably at the same place, that I do work at.

I see the future of zines as a larger part of what Jacksonville and Florida is about. Our collection here is great and items circulate rampantly. On the librarian level, we just presented at the Florida Library Association conference to roaring optimism. People are scheduling us to teach classes about how to start a zine collection. I’m hoping the local populous answers this collection’s existence, answers the authors whose work are represented with works of their own. What you do, what you write, what you create can be part of the library. It’s not lowering the bar for what we catalog – we use the same standards any other department does. It’s adjusting the aperture of our collection. We’re letting in more light, more opinions, more voices. The goal of a library it is to create equality, to level the playing field. Any economic background or any ethnic group, the library is here for you to use. Now, more than ever, it’s here not just for its community to become it’s patron, but part of its collection.

B: Have you ever stolen a book?

JJ: How dare you! I work at a library!

Inspired by Roberto Bolaño, who called it his favorite book, sections of Adam Thirlwell’s The Delighted States, Time’s Flow Stemmed’s recent review, and my own sense of literary duty, I picked up Edith Grossman’s translation of Miguel de Cervantes’ epic Don Quixote last week.

I’ve read chunks of the book over the years, but I’ve probably read more about it than I have the thing itself–never a good thing for a reader who aspires to literary criticism, I suppose. Anyway. I’m surprised at a few things so far. First–and I don’t know if it’s an effect of Grossman’s translation–but the book is very easy to read–breezy, almost. Not what I was expecting for a 400 year old tome famous for dismantling high/low distinctions. I’m also surprised at how terribly sad the book is. Most critics cite the book’s humor, its farcical depiction of Don Quixote as a satire on romanticism and erudition. But it’s also about a guy who’s batshit insane, who repeatedly attacks those he comes into contact with, and who also catches a beating himself now and then.

My goal is to finish it this summer–or at least the first book, anyway. The restaurant I ate lunch in today flaunted statues of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, which I would take to be an auspicious sign if I believed in such things (I don’t). I couldn’t really get a good picture of both with my phone’s camera so I did my best for a headshot of Quixote. The sun’s light seems to obscure him but perhaps that’s appropriate.

Big kudos to Craig Ferman who tracked down and posted an obscure 1996 Details magazine profile on David Foster Wallace by David Strietfield. You can read the full profile here. Here are a few (heartbreaking) excerpts:

He doesn’t want Infinite Jest to be seen as autobiography, which it’s not. On the other hand, if Wallace hadn’t been hospitalized in 1988 and put on a suicide watch, he might not have written so accurately about Kate, a character in Infinite Jest who keeps trying to die: “It’s like something horrible is about to happen,” she explains to her doctor, “there’s the feeling that there’s something you have to do right away to stop it but you don’t know what it is you have to do, and then it’s happening, too, the whole horrible time, it’s about to happen and also it’s happening all at the same time.” . . .

Unlike some of his characters, Wallace managed to extricate himself from the downward spiral before the damage became permanent—these days, he won’t even drink beer. Moreover, he got the raw impetus for a new book. By this point, Wallace was living in upstate New York, in an apartment so small that he had to move everything onto the bed when he wanted to write. “It was,” he says, “like spending two years in a submarine.”

Recently he found a Mennonite house of worship, which he finds sympathetic even if the hymns are impossible to sing. “The more I believe in something, and the more I take something other than me seriously, the less bored I am, the less self-hating. I get less scared. When I was going through that hard time a few years ago, I was scared all the time.” It’s not a trip he ever plans to take again.

The Believer‘s annual reader survey is always kinda sorta interesting. Here’s the top 20; linked titles go to Biblioklept reviews:

Read the rest of the list–honorable mentions–here. Read Biblioklept’s Best of 2009 list here.

Vice Magazine has published an excerpt from William T. Vollmann’s new book Kissing the Mask: Beauty, Understatement, and Femininity in Japanese Noh Theater. Read the excerpt here. The picture above is Mr. Vollmann in drag, one of the themes of his new book. Here is an excerpt from Vice‘s excerpt:

The best mask of my self (never mind my soul) may well be a chujo; my forehead will soon begin to wrinkle in a pattern like roots, and I often bear the sparse mustache, gaping mouth, and blackened teeth of the loyal bewildered lieutenant; perhaps I belong to the Komparu school. What the artist inscribed on the back of my face I will never know, being unable to see myself objectively the way a professional Noh actor would. Most of the time I am a sturdy man who wears the same clothes often, preferring garments of lifelong reliability; I shave carelessly and shrug off my latest wrinkles, because anyhow I never possessed even a waki’s hope of being beautiful, nor felt the loss.

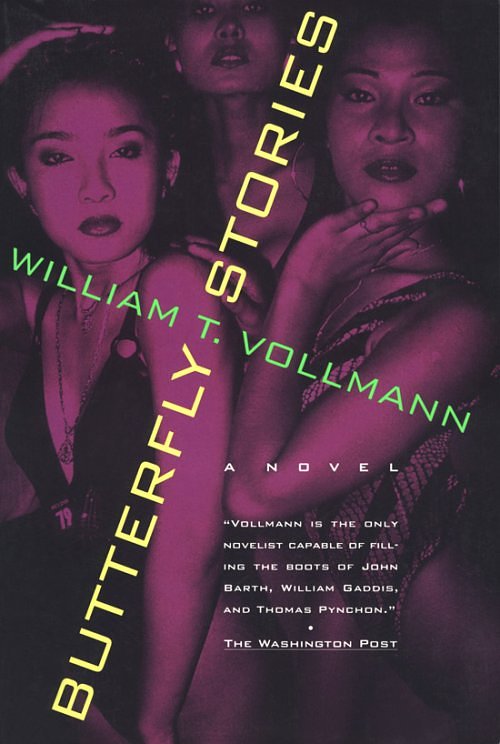

In his 1994 novel Butterfly Stories, William T. Vollmann explores the intense cost of unrelenting idealism. Butterfly Stories is a tragic-comic bildungsroman centered around the life of a protagonist who is almost certainly a semi-autobiographical stand-in for Vollmann. He’s never named in the text; few of the characters are. Instead, he goes by various appellations: the butterfly boy, the boy who wanted to be a journalist, the journalist, the husband. These names square with the protagonist’s painful idealism. He’s a professional alien, a traveler who reports on all the beautiful ugly poor places we Quiet (Ugly) Americans forget about (or never know of in the first place). The main set piece in Butterfly Stories takes place in Thailand and Cambodia:

Once upon a time a journalist and a photographer set out to whore their way across Asia. They got a New York magazine to pay for it. They each armed themselves with a tube of coll soft K-Y jelly and a box of Trojans. The photographer, who knew such essential Thai phrases as: very beautiful!, how much?, thank you and I’m gonna knock you around! (topsa-lopsa-lei), preferred the extra-strength lubricated, while the journalist selected the non-lubricated with special receptacle end. The journalist never tried the photographer’s condoms because he didn’t even use his own as much as (to be honest) he should have; but the photographer, who tried both, decided that the journalist had really made the right decision from a standpoint of friction and hence sensation; so that is the real moral of this story, and those who don’t want anything but morals need read no further.

I’ve quoted the passage at length because I think it delineates a good deal of Vollmann’s program very quickly: whoring-as-gonzo-journalism, a foreshadowing of the sexual grotesquerie to come, blackly ironic humor, and an uncomfortable gap between protagonist and narrator. It’s that gap between the narrator’s ironic detachment and the journalist’s earnest search for meaning–and love–in a world of violence and prostitution that made the book rewarding for me. However, I suspect many will not enjoy (perhaps even hate) this disconnect. The journalist falls in love with several prostitutes throughout the course of the novel, fixating on a Cambodian girl named Vanna in particular. His obsession with Vanna overcomes him, surpasses any rational course of action, and leads him to divorce his wife back in San Francisco in the hopes of marrying a girl he, over time, can no longer even visualize. In short, idealism tortures the protagonist; he’s in love with the idea of love. Late in the novel, he thinks (his thinking framed by the narrator, of course):

Better not to try anything than to be wicked! — That’s how most people acted, and they were probably right, dying their lumpish lives without collecting more than their share of the general blame; but he’d do whatever he was called to do . . .

And later, hallucinating in one of his STD-fueled fevers, he remembers the bully that tormented him back when he was the butterfly boy: “I’m not afraid of you anymore . . . Because I have someone whose life means more to me than mine.” The protagonist’s unrelentingly romanticized view of self-sacrifice is ultimately a defense mechanism against the world’s (equally unrelenting) Darwinian violence.

Vollmann’s milieu of disease-infested, war-torn, economically depressed lands dramatizes this conflict. The violence of the Khmer Rouge, the depravity of prostitution, and the specter of AIDS underpin the novel, and are never mere props for Vollmann, who places his protagonist in a paradoxically privileged vantage point from which to observe, investigate–or ignore–the atrocities of poverty. The book succeeds because of the tension between the narrator’s judgmental, ironic perspective and the protagonist’s big-hearted but ultimately facile dream of a self-sacrificing love. The narrator sees–and lets us see–the ironic selfishness of the protagonist’s dream to save the world, one prostitute at a time.

Just under 300 pages and larded with the author’s spidery black-ink sketches, Butterfly Stories is one of Vollmann’s shorter and more digestible (if that word may be used) volumes. It is bleakly funny, often depressing, and filled with erudite asides on Nobel prizewinners, transvestites, and the benefits of whiskey. And benadryl. Can’t forget the benadryl. Vollmann has an astounding gift for crafting concrete sentences that burst into blistering abstraction, but he can also drift rather aimlessly at times. Does he have an editor? What other literary writer can put out a book of at least 500 pages every year? Butterfly Stories may be a good start for those interested in Vollmann but daunted by his prolific output. It will also repel many readers with its grotesque depictions of sex, which recall Henry Miller and the best of Charles Bukowksi. I liked it very much. Recommended.

Cartoonist Kate Beaton lampoons F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby at her site Hark, A Vagrant. Wonderful send-up of what has to be one of America’s most overrated novels.

Next month (May 20th, 2010 to be precise), the fine folks at indie publisher Melville House will honor the best–and worst–book trailers. The invite promises awards for “Best Cameo,” “Best Author Appearance,” and, of course, “Best Trailer” (“both Big and Low budgets”). Melville House honcho Dennis Loy Johnson will host and author John Wray (Lowboy) will be among the special cadre of envelope-openers. Judges include Carolyn Kellogg (LA Times) and Slate’s Troy Patterson, who wondered if books really needed trailers last year. Nominate trailers here. Not sure how I feel about book trailers, but I like this one for Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, probably mostly because he reads the damn thing and it cracks me up–

ReadRollShow‘s Dave Weich interviews Sam Lipsyte. Great little short clips, perfect for internet viewing. They have three up so far, all embedded below–

There are two distinct ironies in the title of George V. Higgins’s landmark 1970 novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The first is the word “friends” to describe the collection of folks on both sides of the law who Coyle tries to get over on in order to get out of an upcoming prison sentence (of course, most of these folks are looking to use or set up Coyle in turn). The second irony is that Eddie Coyle (aka Eddie Fingers aka “the stocky man”) is not so much the headliner here as he is the catalyst in a sharp and gritty tale of Boston gangsters, gunrunners, student radicals, cops, state police, and federal agents.

Like David Simon did three decades later in his Baltimore opus The Wire, Higgins throws his audience into the deep end. Coyle features almost no exposition. Instead Higgins, a former U.S. Attorney, forwards his intricate and fast-paced plot using machine-gun dialogue. While many crime writers fall for the lure of hyperbolic argot, Higgins’s dialogue rings very true and very raw. He trusts the reader to sort out the complex relationships between hustlers and dupes, cops and finks from their conversations alone; the rest of the prose is reserved for tight, cinematic descriptions of gritty urban Boston at the end of the 1960s. The imagery is straight out of a Scorcese film, and like that director, Higgins has a wonderful gift for showing his audience action without getting in the way. Coyle features a description of a bank robbery that is so clean, precise, and sharp that I wouldn’t be surprised to hear that someone somewhere had used it as a how-to manual.

Higgins also spares authorial intrusion when it comes to a moral voice in his novel. There are certainly bad guys here, to be sure, but they are complex and human, just like the cops and feds who hunt them. In this sense, Coyle is the prototype of a type of crime fiction that came to rise in the cinema of the ’70s–gritty actioners that viewed crime and punishment through a lens of absolute ambiguity. At the same time, Coyle doesn’t unravel into a mere shaggy dog story–there’s a definite conclusion to the story here, even if it doesn’t satisfy the district attorney who tries to make sense of it all (like, in a metaphysical sense) at the end.

I’ve read more crime fiction in the past year than I ever have before, inspired perhaps by “The Part About the Crimes” in Bolaño’s 2666 or Jonathan Lethem’s forays into noir. I wrote a little bit about this the other week when I praised Denis Johnson’s noveau-noir exercise Nobody Move for its purity and its “willingness to be what it is” (whatever that means). (The tone of Nobody Move is downright lighthearted next to Coyle. Not that they need to be compared–I enjoyed both very much). What I did not directly address in that post is my own prejudice against genre fiction, a prejudice that inflamed me in my early teens to such a degree that I probably outright disregarded a lot of great writing. But there’s always more great writing out there than one can read in a lifetime, so why dwell on the past? Suffice to say that The Friends of Eddie Coyle should correct any prejudicial notions of the limits of crime fiction. Highly recommended.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle 40th Anniversary Edition with a new introduction by Dennis Lehane is new this month from Picador.

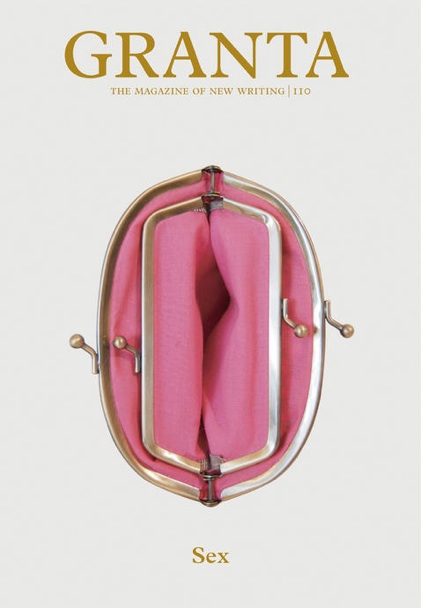

Subtly titled Sex, issue 110 of the long-running literary journal Granta hits stands this week, and it looks like a doozy. There’s a story by Roberto Bolaño called “The Redhead” about “a disturbing encounter between an eighteen-year-old girl and a narcotics cop.” Charming. No description for Tom McCarthy’s “The Spa,” but presumably it will involve sex, and Dave Eggers’s drawings “Four Animals Contemplating Sex” promises to be self-descriptive. Lots of other stuff too, of course. Order Granta 110 here. The journal has also produced short videos for four of the pieces in Sex, all directed by Luke Seomore and Joseph Bull. You can see them at the oh-so-cleverly titled website This is not a purse; the vid for Bolaño’s “The Redhead” is embedded below.

George Washington was a biblioklept. MobyLives hipped us to Ed Pilkington’s Guardian article. From the article:

George Washington was a biblioklept. MobyLives hipped us to Ed Pilkington’s Guardian article. From the article:

Founder of a nation, trouncer of the English, God-fearing family man: all in all, George Washington has enjoyed a pretty decent reputation. Until now, that is.

The hero who crossed the Delaware river may not have been quite so squeaky clean when it came to borrowing library books.

The New York Society Library, the city’s only lender of books at the time of Washington’s presidency, has revealed that the first American president took out two volumes and pointedly failed to return them.

At today’s prices, adjusted for inflation, he would face a late fine of $300,000.

The library’s ledgers show that Washington took out the books on 5 October 1789, some five months into his presidency at a time when New York was still the capital. They were an essay on international affairs called Law of Nations and the twelfth volume of a 14-volume collection of debates from the English House of Commons.

The ledger simply referred to the borrower as “President” in quill pen, and had no return date.

Sylvia Beach was the nexus point for Modernist and ex-pat literature for much of the first half of the twentieth century, running the Left Bank bookstore Shakespeare & Company until the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1941. She was the first publisher of Joyce’s Ulysses, she translated Paul Valéry into English, and was close friends to a good many great writers, including William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, H.D., and Ernest Hemingway. In The Letters of Sylvia Beach, editor Keri Walsh compiles many of Beach’s letters from 1901 to just before her death in 1962. Framed by a concise biographical introduction and a useful glossary of correspondents, Letters reveals private insights into a fascinating literary period. There’s a sweetness to Beach’s letters, whether she’s inviting the Fitzgeralds to come to a dinner party or asking Richard Wright (“Dick”) how much he thinks a fair price for a record player is. The Letters of Sylvia Beach is out now from Columbia UP.

Sylvia Beach was the nexus point for Modernist and ex-pat literature for much of the first half of the twentieth century, running the Left Bank bookstore Shakespeare & Company until the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1941. She was the first publisher of Joyce’s Ulysses, she translated Paul Valéry into English, and was close friends to a good many great writers, including William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, H.D., and Ernest Hemingway. In The Letters of Sylvia Beach, editor Keri Walsh compiles many of Beach’s letters from 1901 to just before her death in 1962. Framed by a concise biographical introduction and a useful glossary of correspondents, Letters reveals private insights into a fascinating literary period. There’s a sweetness to Beach’s letters, whether she’s inviting the Fitzgeralds to come to a dinner party or asking Richard Wright (“Dick”) how much he thinks a fair price for a record player is. The Letters of Sylvia Beach is out now from Columbia UP.

I’m a couple of chapters into William T. Vollmann’s 1993 novel Butterfly Stories, one of his (three? four? Dude’s prolific) books about prostitution. The bullied butterfly grows up to be a boy who wants to be a journalist and then a journalist/inept sex tourist in southeast Asia. Good stuff. Here’s a mordantly elegant passage:

I’m a couple of chapters into William T. Vollmann’s 1993 novel Butterfly Stories, one of his (three? four? Dude’s prolific) books about prostitution. The bullied butterfly grows up to be a boy who wants to be a journalist and then a journalist/inept sex tourist in southeast Asia. Good stuff. Here’s a mordantly elegant passage:

Once he began to combine cutting his wrists and half-asphyxiating himself he believed that he’d found the ideal. Afterwards he’d dream of mummy sex with the gentle girl, by which he meant her body being suspended ropelessly above him, then slowly drifting down; when her knee touched his leg he jerked and then went limp there; her hands reached his hands, which died; her breasts rolled softly upon his heart which fibrillated and stopped; finally she lay on top of him, quite docile and still soft . . . He knew that the others didn’t like mummy sex, but that was because they didn’t understand it; they thought that it must be cold; they thought that she must paint her mouth with something to make it look black and smell horrible and soften like something rotten . . . He wanted to open her up until the pelvis snapped like breaking a wishbone. Would that be mummy sex?

Here’s a one-star review of the book from Amazon: “This book is a sordid collection of junk. I picked it out at random from a library shelf and did not enjoy/like/sympathize with even one thing about it. Don’t waste your time.” Guy didn’t like the mummy sex, I guess.

Been working through my reader’s copy of Dave Eggers’s The Wild Things, new in trade paperback from Vintage. I’m having a hard time envisioning a kind of review of the book that escapes the context of the book; that it’s a novelization of a movie script of a Maurice Sendak book of maybe a few dozen words. I loved that book growing up, so no reason that it should be adapted into a feature film, but hoped for the best due to Eggers’s involvement and the fact that the incomparable Spike Jonze was at the rudder. Or helm. Or whatever naval metaphor you wish. Anyway, I absolutely hated the movie–it was mostly melancholy and downright depressing at times. Whereas Sendak’s book channels the joys of transgressive energy while reiterating the need for stable familial order, Jonze’s movie was all sorrow and loss, the hangover of youth, each ecstasy overshadowed in darkness. Too much yin, not enough yang. Anyway. I’ll try to give the book its proper, fair due on its own terms without all that baggage. Full review forthcoming.

Been working through my reader’s copy of Dave Eggers’s The Wild Things, new in trade paperback from Vintage. I’m having a hard time envisioning a kind of review of the book that escapes the context of the book; that it’s a novelization of a movie script of a Maurice Sendak book of maybe a few dozen words. I loved that book growing up, so no reason that it should be adapted into a feature film, but hoped for the best due to Eggers’s involvement and the fact that the incomparable Spike Jonze was at the rudder. Or helm. Or whatever naval metaphor you wish. Anyway, I absolutely hated the movie–it was mostly melancholy and downright depressing at times. Whereas Sendak’s book channels the joys of transgressive energy while reiterating the need for stable familial order, Jonze’s movie was all sorrow and loss, the hangover of youth, each ecstasy overshadowed in darkness. Too much yin, not enough yang. Anyway. I’ll try to give the book its proper, fair due on its own terms without all that baggage. Full review forthcoming.

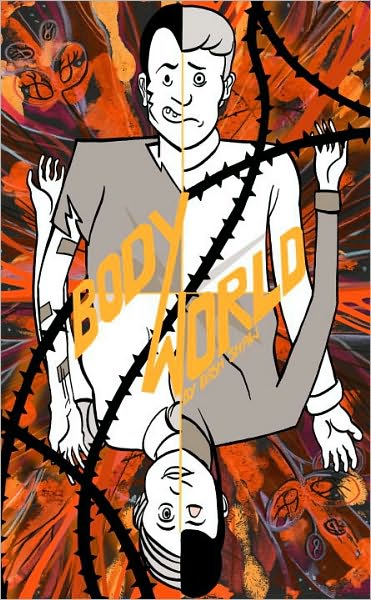

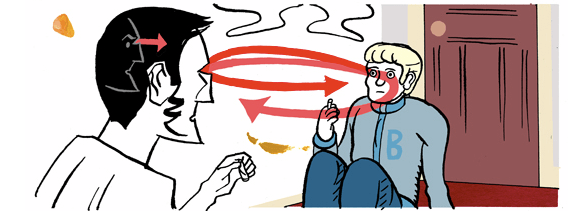

In the future Dash Shaw proposes in his graphic novel BodyWorld, the Second Civil War and rapid industrial growth have left most of America a concrete sprawl by 2060. An exception is Boney Borough, a (literal) green zone somewhere on the Atlantic seaboard. This small secluded town is a new Eden in an otherwise gray world. Enter Professor Paulie Panther, a fuck-up par excellence. He goes to Boney Borough as part of a freelance mission to find out about a new, strange plant he’s found there via the internet. Professor Panther, you see, is a botanist and poet, a would-be scientist who finds out about the psychopharmacological properties of plants by smoking them up in big fat joints (when he’s not too busy trying to commit suicide or stumbling around on one or more of the various drugs to which he’s addicted). Professor Panther is the perfect acerbic foil to the homogeneous folk of Boney Borough. He gets hot for teacher Jem Jewel, turns-on Peach Pearl, the small town girl who wants to go to the big city, and pisses off and confuses her dumb jock boyfriend Billy-Bob Borg. The alliterative names (along with Shaw’s sharp, cartoonish style) recall–and subvert–the classic all-Americanism of Archie comics. Professor Panther soon discovers that the mystery plant, when smoked, grants the user strange telepathic abilities–namely, users sense the “body-mind” of the bodies of others around them.

The plant’s telepathic effects allow Shaw to explore what happens within a literalized I-see-you-seeing-me-seeing-you-seeing-me (seeing-y0u-seeing-me . . .) structure. His bright Pop Art goes Cubist in psychedelic trip scenes, superimposing images to show a surreal conflation of not just the melding of two people’s pasts and presents, but those people’s perceptions of past and present. Very heady stuff–but seeing Shaw’s work is superior to my description, of course. Observe, as Panther sees Pearl seeing Panther seeing Pearl idealizing their attempt at romance:

BodyWorld is sardonically humorous in its psychoanalytic visions, guided in no small part by Professor Panther’s hilarious outsider perspective, but also tempered by Shaw’s larger project, a sci-fi satire of American exurbanist insularity. We wrote earlier this month about science fiction’s tendency to work within the dichotomy of wastelands and green zones, and Shaw’s work is no exception. His marvelous trick is to keep us within the green zone of Boney Borough the whole time and to make us identify with a waster, Panther. The greatest irony is that in this futurist vision, the zombies are the ones in the green zone.

Not everyone’s a conformist though. There are exceptions, of course, especially in the seedy Outer Rim where Panther takes up transient residence. We meet a psychotic latter-day Johnny Appleseed who certainly shares Panther’s weirdo proclivities. The episode is a marvelous spoof on the corny “origin stories” standard in Golden and Silver Age comics, with Shaw’s treatment more loving than mocking. To tell more about this weirdo might spoil the climax of Shaw’s graphic novel, and we don’t want to do that, of course, because you’re going to want to read it, aren’t you? Suffice to say that it’s part and parcel of Shaw’s program, a sweet and sour subversion of the 1950s comics and contemporary conformist groupthink politics. Shaw owes some debt to the neat precision, spacing, and rhythm of Chris Ware, as well as the haunting inks and sharp wit of Charles Burns but it would be a mistake to see this young talent as anything but original. Still, while we’re making comparisons: Richard Kelly could make a messy, sprawling treasure of a film out of BodyWorld.

You can read all of BodyWorld now at Shaw’s website, or you can do what I did and read Pantheon’s new graphic novel version (Pantheon, you will remember, brought us the David Mazzucchelli’s outstanding graphic novel Asterios Polyp). Either way, you should read it. Highly recommended.

Christopher Hitchens on George Orwell’s Animal Farm in this weekend’s issue of The Guardian. From the essay:

It is sobering to consider how close this novel came to remaining unpublished. Having survived Hitler’s bombing, the rather battered manuscript was sent to the office of TS Eliot, then an important editor at Faber & Faber. Eliot, a friendly acquaintance of Orwell’s, was a political and cultural conservative, not to say reactionary. But, perhaps influenced by Britain’s alliance with Moscow, he rejected the book on the grounds that it seemed too “Trotskyite”. He also told Orwell that his choice of pigs as rulers was an unfortunate one, and that readers might draw the conclusion that what was needed was “more public-spirited pigs”. This was not perhaps as fatuous as the turn-down that Orwell received from the Dial Press in New York, which solemnly informed him that stories about animals found no market in the US. And this in the land of Disney . . .

There’s an admirable precision to Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move, a dark and funny crime caper originally serialized in Playboy over four months in 2008, now available in trade paperback from Picador. Johnson limits himself to a handful of characters, a span of a few days, and four fifty-page segments to tell his story. Johnson’s economy resonates from his tight plotting and structure down to his cool, concise sentences. He works in noir archetypes, to be sure–there’s the hard-luck loser in over his head, the femme fatale with a troubled past (and present), the sadistic thug and his moll, and the sinister mastermind. Johnson’s feat here is to present all of this in a manner that’s simultaneously invigorating to the genre but also a confirmation of its pleasures.

Consider Johnson’s erstwhile protagonist, Jimmy Luntz. The name alone seems to tell us everything about this guy, a lousy gambler who spends much of his time on the run. He owes money to the wrong guys, and when a gorilla appropriately named Gambol comes to collect, Luntz makes the mistake of shooting but not killing him. Johnson traffics in immediacy in Nobody Move–there’s not a lot of backstory or dwelling on psychological motivation, thankfully–but he does offer up the occasional nugget, like this one:

Early in his teens Luntz had fought Golden Gloves. Clumsy in the ring, he’d distinguished himself the wrong way–the only boy to get knocked out twice. He’d spent two years at it. His secret was that he’d never, before or since, felt so comfortable or so at home as when lying on his back listening to the far-off music of the referee’s ten-count.

And that’s all the personal history we really need about Luntz. It’s the gaps in the story that are so engaging, that force the reader to play the role of detective in this crime story. To this end, Johnson starts the story in media res, with Luntz leaving a disappointing competition performance of his barbershop chorus. He spends much of the novel’s first half still in his white tux. The novel’s end — well, I won’t spoil the end, of course — but let’s just say that the end of the novel finds our characters poised for further nefarious adventures. But there I go, getting ahead of myself. A little more on plot: Gambol, wounded by Jimmy, finds himself being nursed by a woman named Mary. Their nascent relationship is one of the highlights of the book, funny and cruel, a bizarre study in unlikely romance. Meanwhile, Jimmy hooks up with Anita Desilvera, a dark-eyed bombshell with a serious drinking problem and a series of upcoming court dates. They complicate their problems by going on the lam together. Gambol eventually comes looking for Jimmy (he wants to literally eat his testicles) and drama and danger ensue.

Denis Johnson is arguably among the best living American writers today, having produces no fewer than two masterpieces (Tree of Smoke, one of my favorite books of the past ten years, and Jesus’ Son, one of my favorite books ever). So when he wrote a genre fiction piece under a deadline for Playboy, many critics and readers wondered what he was up to. Was he serious? How serious were we supposed to take the work? Did he need the money? The book itself offers some answers. Nobody Move is fantastic as a genre exercise, witty, dark, lean, and hard-boiled, transcending the bad or formulaic writing that can plague the genre’s novels but never trying to transcend its tropes. Put another way, Johnson here demonstrates that he can master a genre that is not his, and that he can do it under the constraints of space and time. That’s quite a feat, if you think about it, especially if you compare Nobody Move to Thomas Pynchon’s recent genre exercise, Inherent Vice, or the detective-centered works of Jonathan Lethem like Motherless Brooklyn and Gun, With Occasional Music. Pynchon’s work is in many ways a covert, loving goof on the genre, but it’s still more or less a “Thomas Pynchon” book. Lethem likes the idea of writing crime noir, but he wants to subvert it, mash it up with sci-fi, see it as a form of post-modern allegory. Roberto Bolaño is almost painfully aware of this in his fiction–his narrator in Distant Star gets to play at being a detective for a bit, but finds that it’s not nearly as fun as he would like it to be. The Savage Detectives views literature and art as a crime scene to puzzle out. And 2666 . . . well, you know about 2666 (hang on wait, you don’t know about 2666? You should really get that taken care of). Or take James Ellroy’s postmoderinst crime fiction, which owes, unwittingly or not, as much to Don DeLillo as it does to Raymond Chandler. These are all great writers, of course. But I think contrasting what they are trying to do with what Johnson is trying to do is instructive.

There’s a purity to Nobody Move, to its utter willingness to simply be what it is–and many folks won’t like that; they may even accuse Johnson of slumming. Perhaps they think it’s easy to write a tight, funny crime novel. Perhaps they know it’s not, and they think that Johnson is being solipsistic, or even mercenary. In any case, Nobody Move will probably stand outside of Johnson’s canon. And that’s unfair. Cinematic and highly visual, it recalls some of the Coen brothers’ finest work, like Blood Simple and The Man Who Wasn’t There, and even Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (minus the messy sprawl). Perhaps the best thing about Nobody Move–other than the sheer pleasure of reading it over a few afternoons, of course–is that it might motivate readers to pick up Jesus’ Son or even Tree of Smoke. For many readers, especially young readers, genre is a vital gateway to what many of us prejudicially call “more serious” literature. So pick up Nobody Move, read it, love it, and then pass it on to someone who needs to know about Denis Johnson. Recommended.

Nobody Move is available in trade paperback from Picador on April 24, 2010.