So, this is Biblioklept’s 500th post [pauses for applause].

Thank you, thank you. To mark the special occasion, we’ve artfully and scientifically compiled a list of the best stuff of the aughties (or 2000s, or whatever you want to call this decade that’s ending so soon). We know the year’s not over yet, and we readily admit that our list is incomplete: we didn’t read every book published in the decade, listen to every record, watch every film, etc. So, feel free to drop a line and let us know who we forgot (or, perhaps, snubbed).

Here, in no particular order, is the best of the past decade:

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Children of Men, The Fiery Furnaces, The Wire, Kill Bill, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikushi (Spirited Away), The Believer, Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” (and its marvelous video), David Foster Wallaces’s essays in Consider the Lobster, Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, Animal Collective, Barack Obama, Terrence Malick’s The New World, Mad Men, Deadwood, Dave Chappelle, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Mitch Hedberg, R. Kelly, YouTube, Drag City Records, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Nathan Rabin’s “My Year of Flops,”

Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, Extras, Harry Potter on Extras, Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Missy Elliott’s “Get Ur Freak On,” Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, Pixar movies–especially the latest three: WALL-E, Up, and Ratatouille, McSweeney’s #13 (the Chris Ware Issue), Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, that time the Shins were on Gilmore Girls, the first six episodes of The OC, Arrested Development, Nintendo Wii, Andre 3000’s “Hey Ya!,” The Office, Will Ferrell, Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, Picador Books, Donnie Darko,

Veronica Mars, The Venture Brothers, Home Movies, the third Harry Potter movie, Wikipedia, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude, DFW’s Oblivion, especially “The Suffering Channel,” Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon commencement address, Wonder Showzen, Toni Morrison’s A Mercy, the totally goofy but totally fun troubadour sequence from Gilmore Girls with Yo La Tengo, Thurston, Kim, and daughter Coco Haley, and Sparks jamming, OutKast’s Stankonia, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Devil’s Backbone, The Orphanage, Cat Power’s “Willie Deadwilder,”Flight of the Conchords, Girl Talk’s Night Ripper, The Daily Show with John Stewart, The Colbert Report,

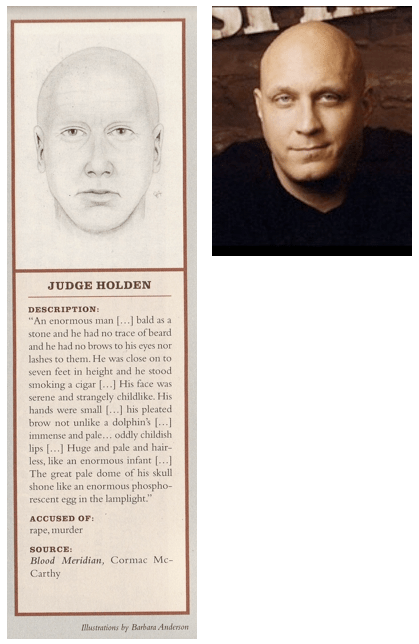

Andy Samberg’s Digital Shorts, Autotune the News, Tim Tebow, Panda Bear’s Person Pitch, Nels Cline’s guitar solo in “Impossible Germany,” Judd Apatow, Be Kind Rewind, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Thrill Jockey Records, I Heart Huckabees, Chris Bachelder’s U.S.!, David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE, Fennesz’s Endless Summer, Gmail, the Coens’ No Country for Old Men, MF Doom (all iterations), Broken Social Scene’s You Forgot It in People, Satrapi’s Persepolis, UGK’s “International Player’s Anthem,” Bob Dylan’s “Things Have Changed,” Bonnie “Prince” Billy,

The Silver Jews’ Tanglewood Numbers, lolcatz, Once, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, web two point oh, 30 Rock, Belle & Sebastian’s “Stay Loose,” It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Philip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass, Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man, WordPress, Jim O’Rourke’s Insignificance, the first season of Battlestar Galactica, Superbad, half a dozen or so short stories by Wells Tower, David Cross’s Shut Up, You Fucking Baby!, Drunk History, the action sequence at the end of Tarantino’s Death Proof (and especially the joyous, headcrushing final shot), Slavoj Žižek’s Violence, The Royal Tennenbaums, the first 20 minutes of Gangs of New York,

Firefox, the increasing and continuing availability of English translations of authors like Roberto Bolaño and W.G. Sebald, Bill Murray, Margot at the Wedding, Rachel Getting Married, Top Chef, The Dirty Projector’s Bitte Orca, Battles’ “Atlas,” Revenge of the Sith, Sarah Vowell, Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, Christoph Waltz’s bravura performance in Inglourious Basterds, the surreal animations of Carson Mell, Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, Tina Fey’s impression of Sarah Palin, David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, Neko Case’s “Star Witness,” Jason Statham, The Pirate Bay, HDTV, Charles Burns’s Black Hole, &c . . .