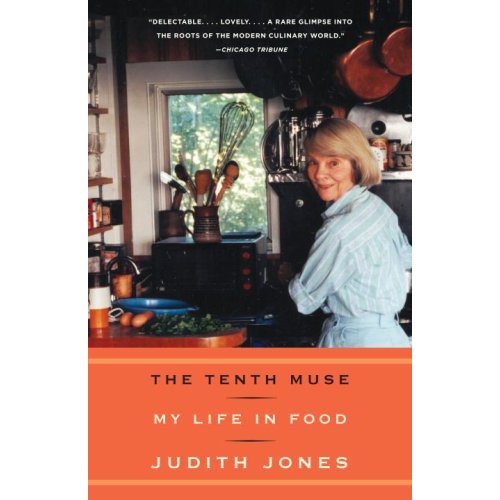

Judith Jones’s memoir The Tenth Muse, aptly subtitled My Life in Food, chronicles the life of one of the most influential foodies you’ve never heard of. The book moves quickly through Jones’s terse blueblooded Vermont childhood, through her time at Bennington College, and her first trip to Paris, all the while keeping Jones’s passion for food as its focus. This passion leads her to move to Paris after her college days, where she and future husband (and fellow writer) Evan Jones can eat pâté to their hearts’ content while palling around with writers, artists, and other beautiful people (even Balthus pops up in her narrative here). After some years of bohemian bliss, Jones returns to the U.S. to champion Julia Child, working hard to get her seminal cook book Mastering the Art of French Cooking to an American audience (she also manages to get The Diary of Anne Frank translated for publication as well). Shocked at the paltry selection of fresh foods in New York City, Jones and her now-husband Evan learn to make many of the fine French foods they enjoyed in their Paris days. At the same time, they continue to introduce a wider audience of Americans to cooks like James Beard, M.F.K. Fisher and Edna Lewis. Through it all, food (rich, thick, luscious French food) remains the primary focus, with the art of writing–and editing–a close second. Jones’s narrative abounds with anecdotes of chefs (Claudia Roden, Lidia Bastianich), editors, and writers (Camus, Capote, Updike), but readers who pine for psychological introspection or juicy melodrama won’t find much to chew on here.

Jones tends to gloss over information that most memoirs would milk for maximum drama. Evan was married when she first began living with him, a fact that would’ve scandalized many women in the 1950s but here goes largely unremarked. Two teenage children are adopted with little explanation or follow-up. Even the focus of Jones’s mastectomy returns to food, her pre-op meal, which Evans sneaks in to the hospital (“good pâté de campagne, some ripe cheese, a baguette, and a bottle of wine”). Also, readers who tend to pay attention to matters of class and economics might find Jones’s complete lack of self-reflection on how her wealth and background have allowed her to live and eat so richly a bit distasteful, particularly when she rails against the state of the modern American kitchen (too unused, or too full of processed, “quick and easy solutions.” Jones would have us killing and dressing beavers we catch on our vast estates, apparently. (Relax, I’m exaggerating (although she does prepare a beaver her son-in-law shoots)–but seriously, preparing a duck for dinner is not nearly as easy as she cheerily suggests)). But ultimately in The Tenth Muse, such lack of reflection simply leaves room for the food, which is really why you want to read this book anyway.

Jones caps off her book with over 80 pages of recipes, lovingly arranged in their own sort of narrative, one that parallels her life story. Jones includes favorite dishes from her early youth (“Spaghetti and Cheese”), plenty of French favorites (“Boudin Blanc,” simple “Baguettes,” “Brains with a Mustard Coating”), and recipes from her country estate (“Gooseberry Tart”). The selection of recipes at the end, “Cooking for One,” inspired by her continued love of complex cooking even after the death of her husband, is particularly poignant (Jones includes seven things to make from one duck).

The Tenth Muse may not meet the usual memoir-reader’s needs for salacious detail or analytical introspection, but those who simply want a glimpse into the life of an influential foodie–and some great recipes to boot–will not be disappointed. Recommended.

The Tenth Muse is now available in paperback from Anchor Books.