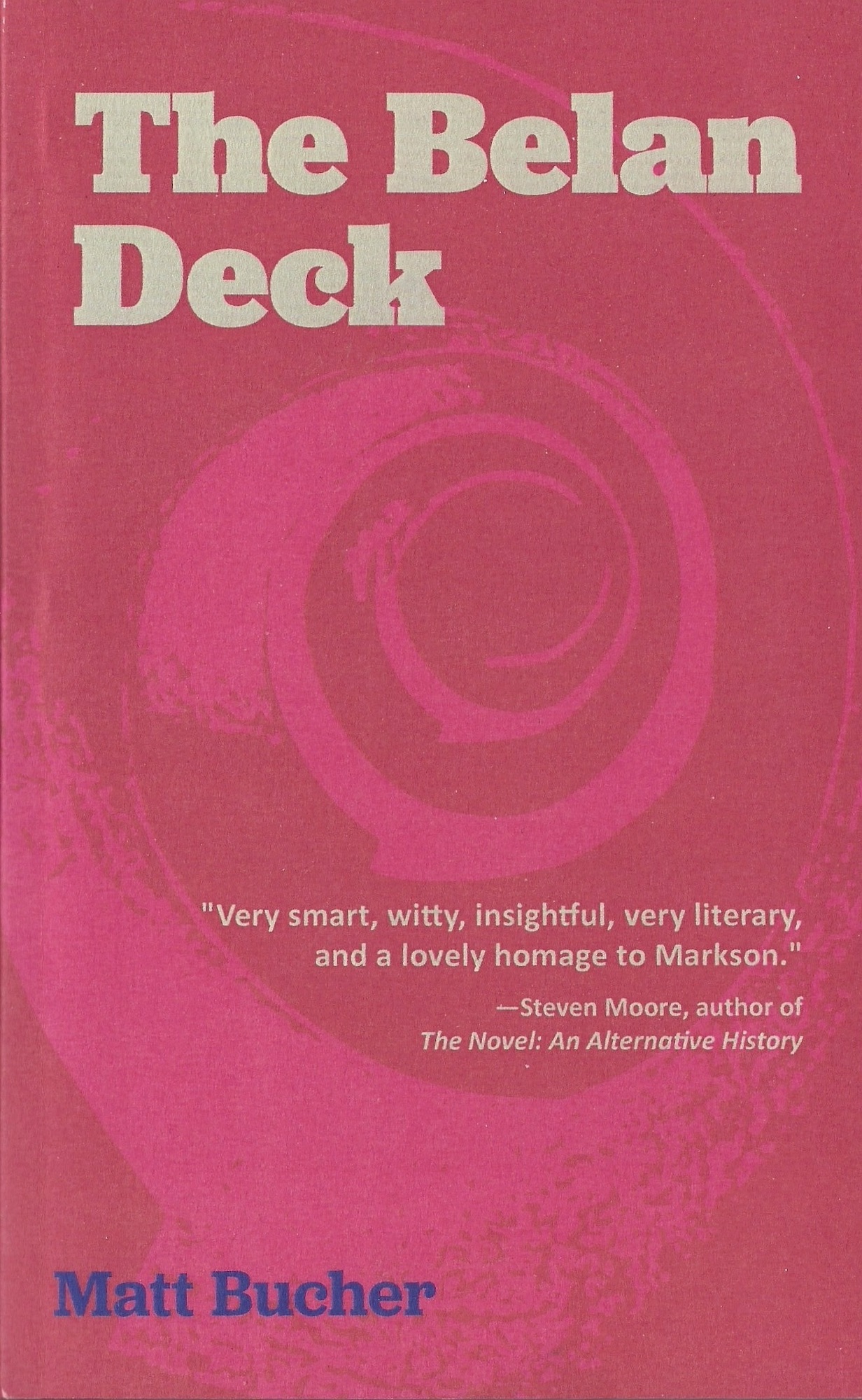

The Belan Deck, Matt Bucher. SSMG Press (2023; second printing). Cover design by David Jensen. 119 pages.

Tag: Books

“The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell),” a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers by G. Cabrera Infante

“The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell)”

a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers

by G. Cabrera Infante

translated by Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with collaboration by Infante

The Story

We arrived in Havana one Friday around three in the afternoon. The heat was oppressive. There was a low ceiling of dense gray, or blackish, clouds. As the boat entered the harbor the breeze that had cooled us off during the crossing suddenly died down. My leg was bothering me again and it was very painful going down the gangplank. Mrs. Campbell followed behind me talking the whole damned time and she found everything, but everything, enchanting: the enchanting little city, the enchanting bay, the enchanting avenue facing the enchanting dock. All I knew was that there was a humidity of 90 or 95 percent and that I was sure my leg was going to bother me the whole weekend. It was, of course, Mrs. Campbell’s brilliant idea to come to such a hot and humid island. I told her so as soon as I was on deck and saw the ceiling of rain clouds over the city. She protested, saying they had sworn to her in the travel agency that it was always, but always, spring in Cuba. Spring my aching foot! We were in the Torrid Zone. That’s what I told her and she answered, “Honey, this is the tropics!”

On the edge of the dock there was this group of enchanting natives playing a guitar and rattling some gourds and shouting infernal noises, the sort of thing that passes for music here. In the background, behind this aboriginal orchestra, there was an open-air tent where they sold the many fruits of the tropical tree of tourism: castanets, brightly painted fans, wooden rattlers, musical sticks, shell necklaces, earthenware pots, hats made of a brittle yellow straw and stuff like that. Mrs. Campbell bought one or two articles of every kind. She was simply enchanted. I told her she should wait till the day we left before making purchases. “Honey,” she said, “they are souvenirs.” She didn’t understand that souvenirs are what you buy when you leave a country. Nor was there any point in explaining. Luckily they were very quick in Customs, which was surprising. They were also very friendly, although they did lay it on a bit thick, if you know what I mean.

I regretted not bringing the car. What’s the point of going by ferry if you don’t take a car? But Mrs. Campbell thought we would waste too much time learning foreign traffic regulations. Actually she was afraid we would have another accident. Now there was one more argument she could throw in for good measure. “Honey, with your leg in this state you simply cannot drive,” she said. “Let’s get a cab.”

We waved down a taxi and a group of natives—more than we needed—helped us with our suitcases. Mrs. Campbell was enchanted by the proverbial Latin courtesy. It was useless to tell her that it was a courtesy you also pay for through your proverbial nose. She would always find them wonderful, even before we landed she knew everything would be just wonderful. When all our baggage and the thousand and one other things Mrs. Campbell had just bought were in the taxi, I helped her in, closed the door in keen competition with the driver and went around to the o

ther door because I could get in there more easily. As a rule I get in first and then Mrs. Campbell gets in, because it’s easier for her that way, but this impractical gesture of courtesy which delighted Mrs. Campbell and which she found “very Latin” gave me the chance to make a mistake I will never forget. It was then that I saw the walking stick.

It wasn’t an ordinary walking stick and this alone should have convinced me not to buy it. It was flashy, meticulously carved and expensive. It’s true that it was made of a rare wood that looked like ebony or something of that sort and that it had been worked with lavish care—exquisite, Mrs. Campbell called it—and translated into dollars it wasn’t really that expensive. All around it there were grotesque carvings of nothing in particular. The stick had a handle shaped like the head of a Negro, male or female—you can never tell with artists—with very ugly features. The whole effect was repulsive. However, I was tempted by it even though I have no taste for knickknacks and I think I would have bought it even if my leg hadn’t been hurting. (Perhaps Mrs. Campbell, when she noticed my curiosity, would have pushed me into buying it.) Needless to say Mrs. Campbell found it beautiful and original and—I have to take a deep breath before I say it—exciting. Women, good God!

We got to the hotel and checked in, congratulating ourselves that our reservations were in order, and went up to our room and took a shower. Ordered a snack from room service and lay down to take a siesta—when in Rome, etc. . . . No, it’s just that it was too hot and there was too much sun and noise outside, and our room was very clean and comfortable and cool, almost cold, with the air-conditioning. It was a good hotel. It’s true it was expensive, but it was worth it. If the Cubans have learned something from us it’s a feeling for comfort and the Nacional is a very comfortable hotel, and what’s even better, it’s efficient. When we woke up it was already dark and we went out to tour the neighborhood.

Outside the hotel we found a cab driver who offered to be our guide. He said his name was Raymond something and showed us a faded and dirty ID card to prove it. Then he took us around that stretch of street Cubans call La Rampa, with its shops and neon signs and people walking every which way. It wasn’t too bad. We wanted to see the Tropicana, which is advertised everywhere as “the most fabulous cabaret in the world,” and Mrs. Campbell had made the journey almost especially to go there. To kill time we went to see a movie we wanted to see in Miami and missed. The theater was near the hotel and it was new and air-conditioned.

We went back to the hotel and changed. Mrs. Campbell insisted I wear my tuxedo. She was going to put on an evening gown. As we were leaving, my leg started hurting again—probably because of the cold air in the theater and the hotel—and I took my walking stick. Mrs. Campbell made no objection. On the contrary, she seemed to find it funny.

The Tropicana is in a place on the outskirts of town. It is a cabaret almost in the jungle. It has gardens full of trees and climbing plants and fountains and colored lights along all the road leading to it. The cabaret has every right to advertise itself as fabulous physically, but the show consists—like all Latin cabarets, I guess—of half-naked women dancing rumbas and singers shouting their stupid songs and crooners in the style of Bing Crosby, but in Spanish. The national drink of Cuba is the daiquiri, a sort of cocktail with ice and rum, which is very good because it is so hot in Cuba—in the street I mean, because the cabaret had the “typical Cuban air-conditioning” as they call it, which means the North Pole encapsuled in a tropical saloon. There’s a twin cabaret in the open air but it wasn’t functioning that night because they were expecting rain. The Cubans proved good meteorologists. We’d only just begun to eat one of those meals they call international cuisine in Cuba, which consist of things that are too salty or full of fat or fried in oil which they follow with a dessert that is much too sweet, when a shower started pouring down with a greater noise than one of those typical bands at full blast. I say this to give some idea of the violence of the rainfall as there are very few things that make more noise than a Cuban band. For Mrs. Campbell this was the high point of sophisticated savagery: the rain, the music, the food, and she was simply enchanted. Everything would have been fine—or at any rate passable; when we switched to drinking whiskey and soda I began to feel almost at home—but for the fact that this stupid maricón of an emcee of the cabaret, not content with introducing the show to the public, started introducing the public to the show, and it even occurred to this fellow to ask our names—I mean all the Americans who were there—and he started introducing us in some godawful travesty of the English language. Not only did he mix me up with the soup people, which is a common enough mistake and one that doesn’t bother me anymore, but he also introduced me as an international playboy. Mrs. Campbell, of course, was on the verge of ecstasy! Continue reading ““The Story of a Stick (With Some Additional Comments by Mrs. Campbell),” a chapter from Three Trapped Tigers by G. Cabrera Infante”

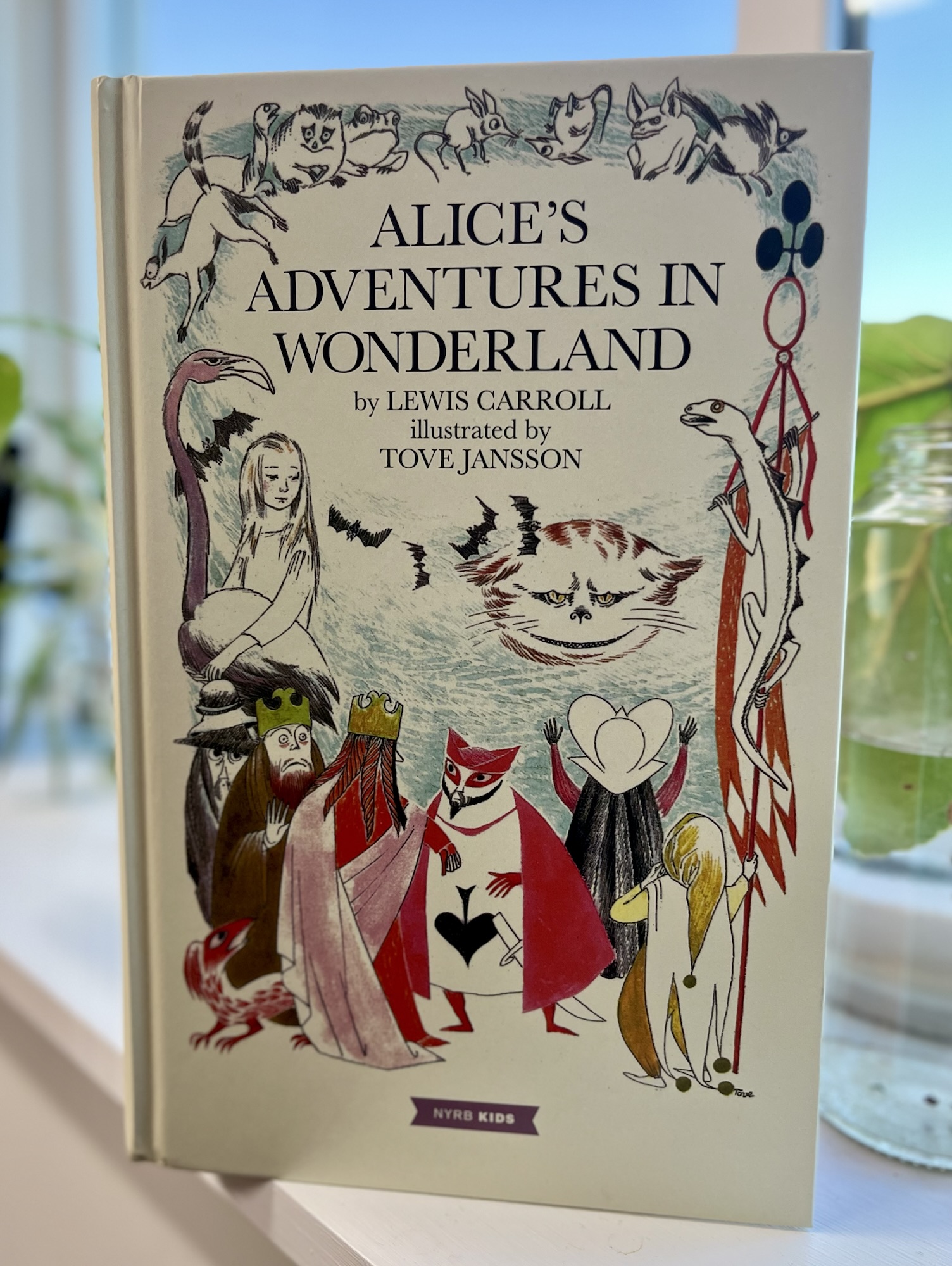

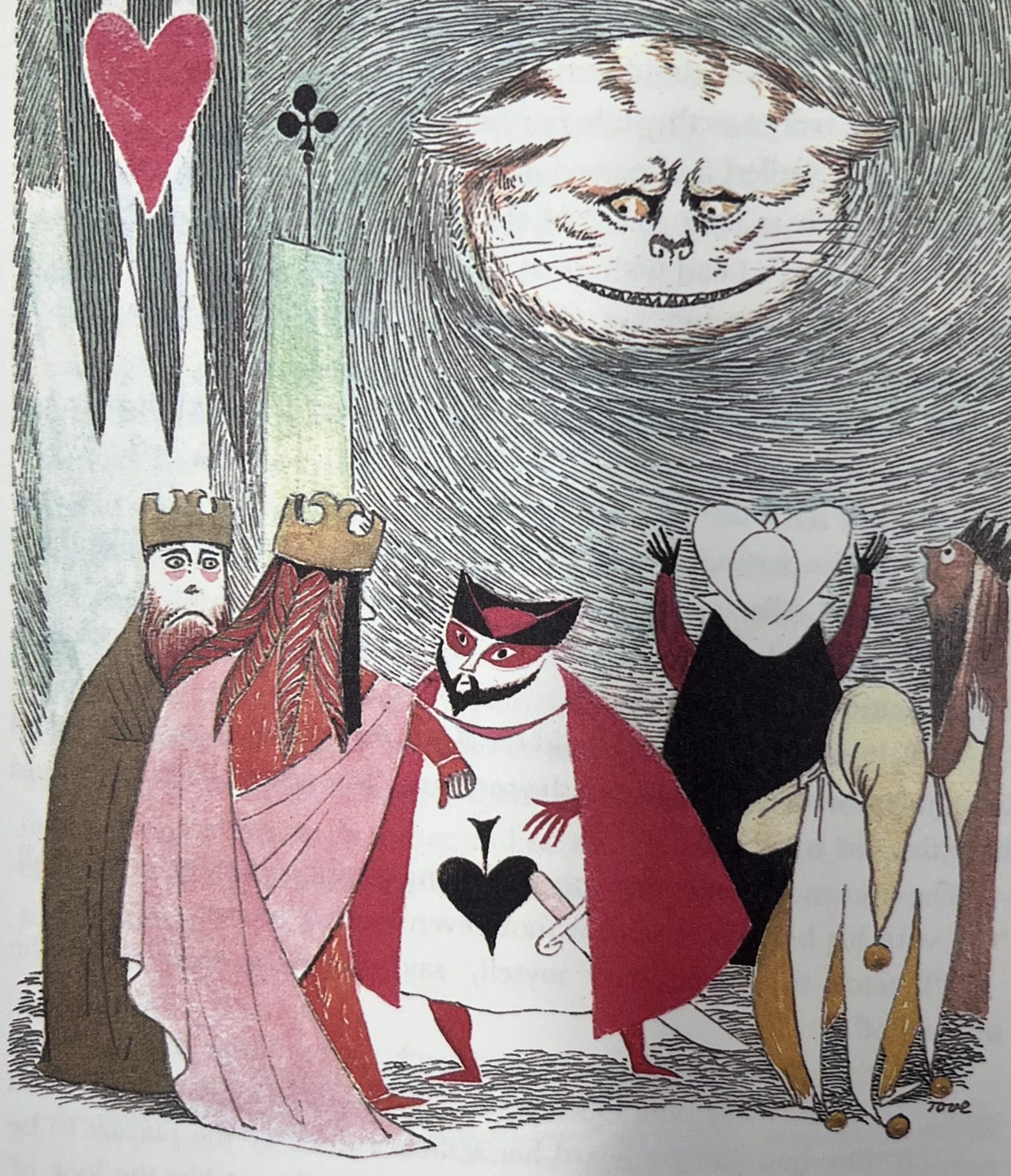

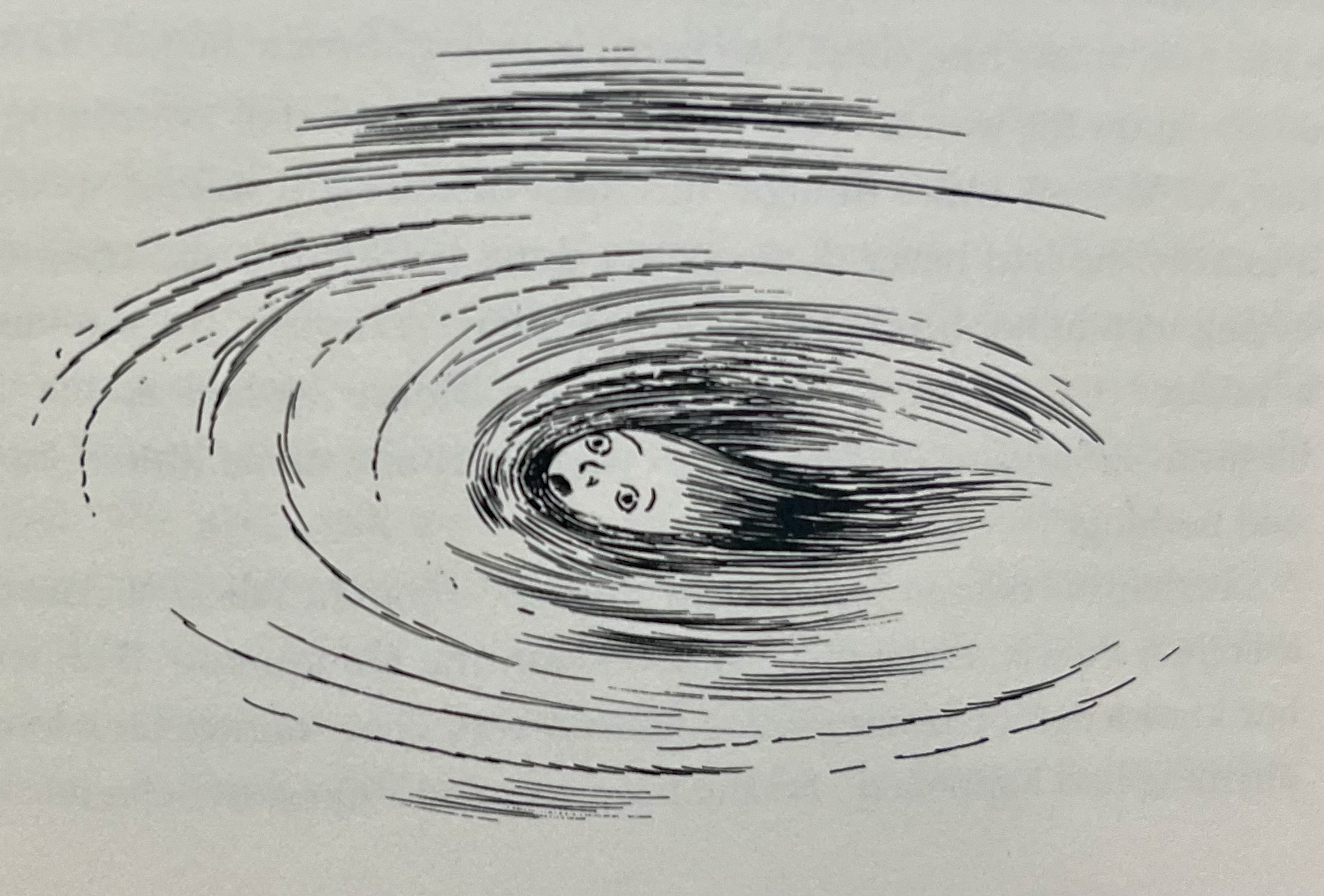

On Tove Jansson’s odd and touching illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

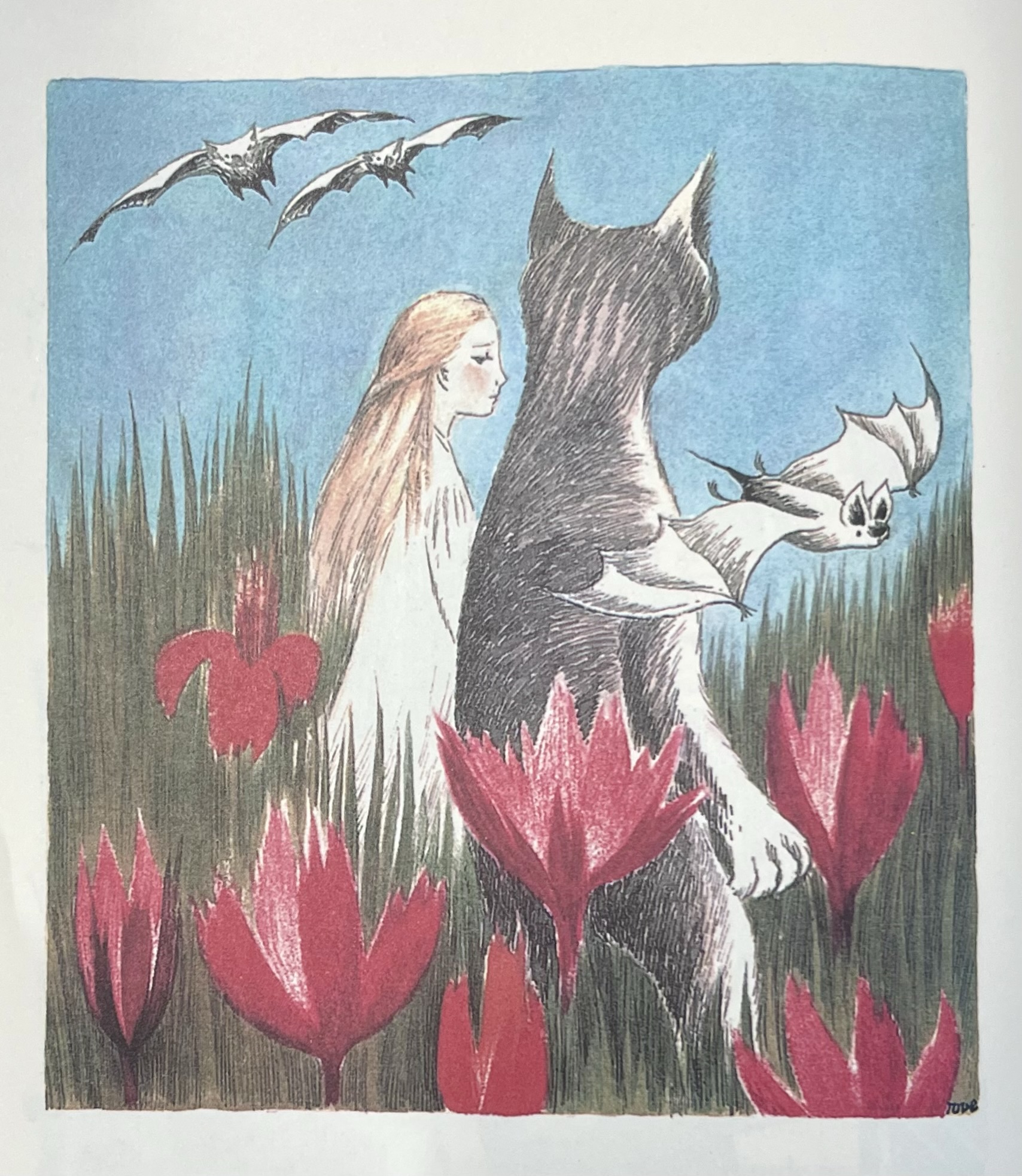

This fall–just in time for the holiday season–the NYRB Kids imprint has published an edition of Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by the Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson. Jansson is most famous for her Moomin books, which remain an influential cult favorite with kids and adults alike. She illustrated Carroll’s Alice in 1966 for a Finnish audience; this NRYB edition is the first English-language version of the book. There are illustrations on almost every page of the book; most are black and white sketches — doodles, portraits, marginalia — but there are also many full-color full-pagers, like this odd image about a dozen pages in:

Here we have Alice and her cat Dinah, transformed into a shadowy, even sinister figure, large, bipedal. Bats float in the background, echoing Goya’s famous print El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. The image accompanies Alice’s initial descent into her underland wonderland: “Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again,” addressing Dinah, who will “miss me very much to-night, I should think!” Wonderlanding if Dinah might catch a bat, which is something like a mouse, maybe, “Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?; for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.” Jansson’s red flowers suggest poppies, contributing to the scene’s slightly-menacing yet dreamlike vibe. The image ultimately echoes the myth of Hades and Persephone.

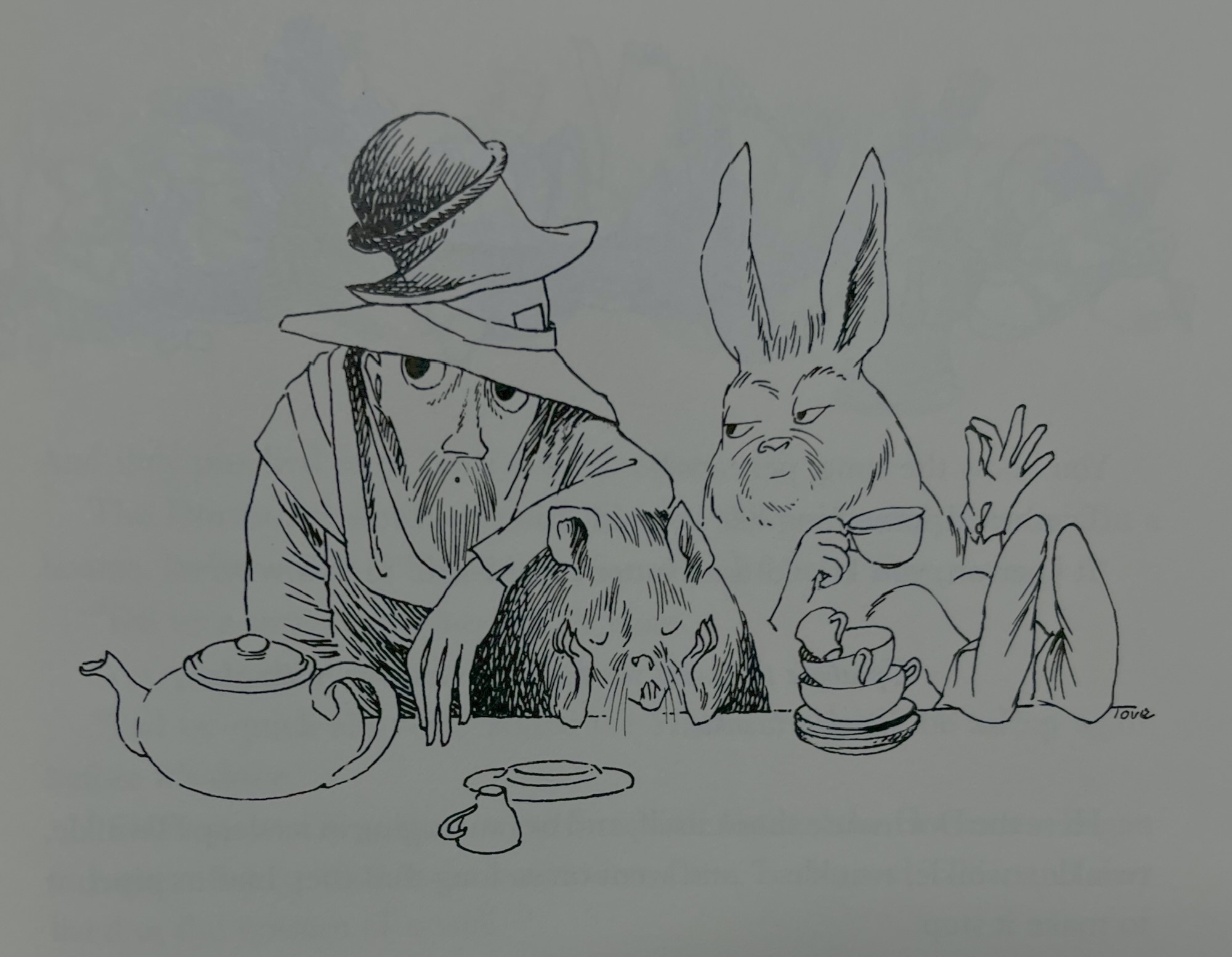

All the classic characters are here, of course, rendered in Jansson’s sensitive ink. Consider this infamous trio —

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head.

I love Jansson’s take on the Hatter; he’s not the outright clown we often see in post-Disneyfied takes on the character, but rather a creature rendered in subtle pathos. The March Hare is smug; the Dormouse is miserable.

And you’ll want a glimpse of the famous Cheshire cat who appears (and disappears) during the Queen’s croquet match:

Jansson’s figures here remind one of the surrealist Remedios Varo’s strange, even ominous characters. Like Varo and fellow surrealist Leonora Carrington, Jansson’s art treads a thin line between whimsical and sinister — a perfect reflection of Carroll’s Alice, which we might remember fondly as a story of magical adventures, when really it is much closer to a horror story, a tale of being sucked into an underworld devoid of reason and logic, ruled by menacing, capricious, and ultimately invisible forces. It is, in short, a true reflection of childhood,m. Great stuff.

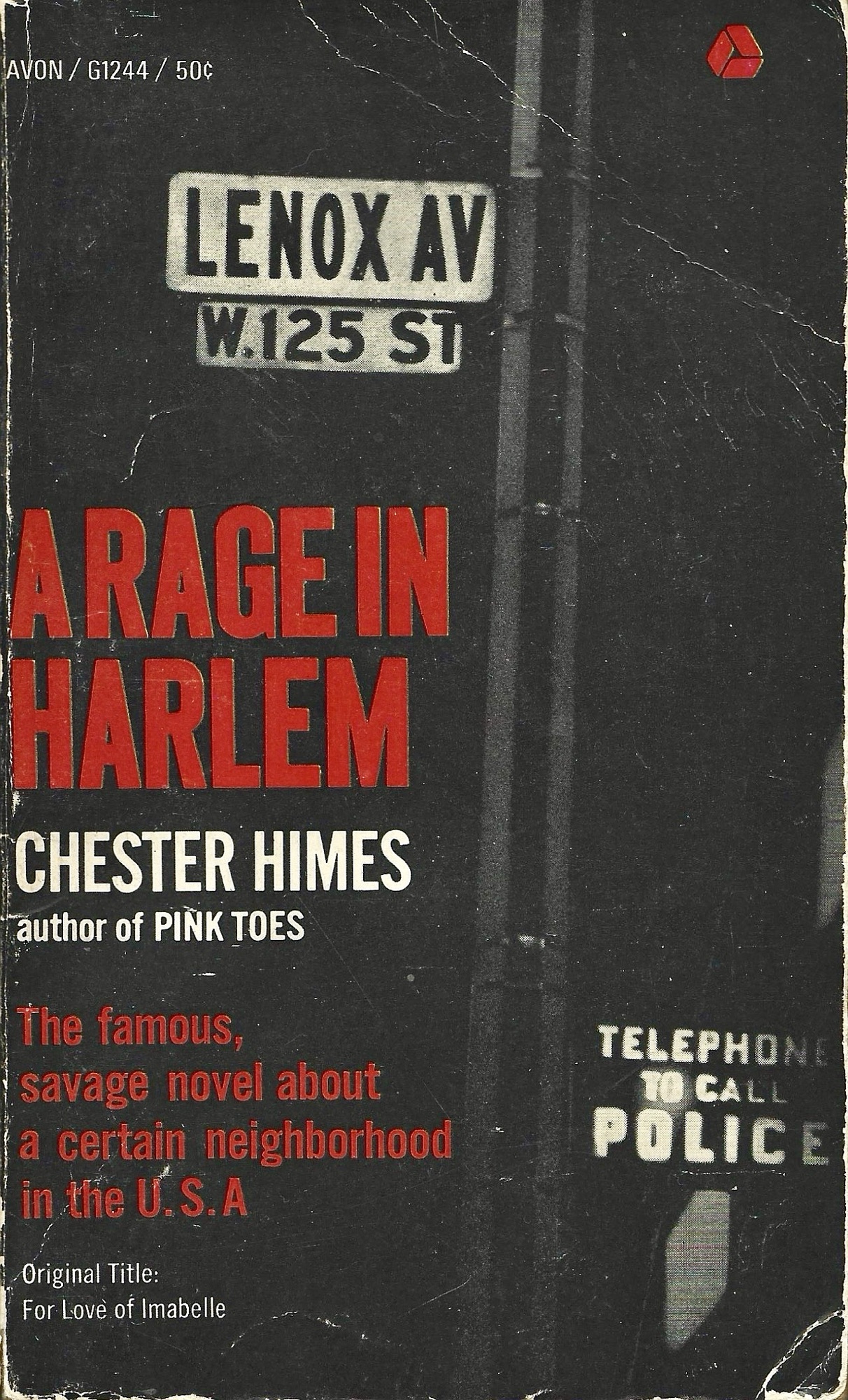

Mass-market Monday | Chester Himes’ A Rage in Harlem

A Rage in Harlem, Chester Himes. Avon Books (1965). No cover artist or designer credited. 192 pages.

Himes’ A Rage in Harlem is a quick, mean, sharp read. I came to Himes via Ishmael Reed, who wrote of the author in a 1991 LA Times review of Himes’ Collected Stories,

James Baldwin, another proud and temperamental genius, said that if he hadn’t left the United States he would have killed someone. The same could be said of Chester Himes, the intellectual and gangster who left the United States for Europe in the 1950s. He achieved fame abroad with his Harlem detective series, which are remarkable for their macabre comic sense and wicked and nasty wit so brilliantly captured in Bill Duke’s A Rage in Harlem.

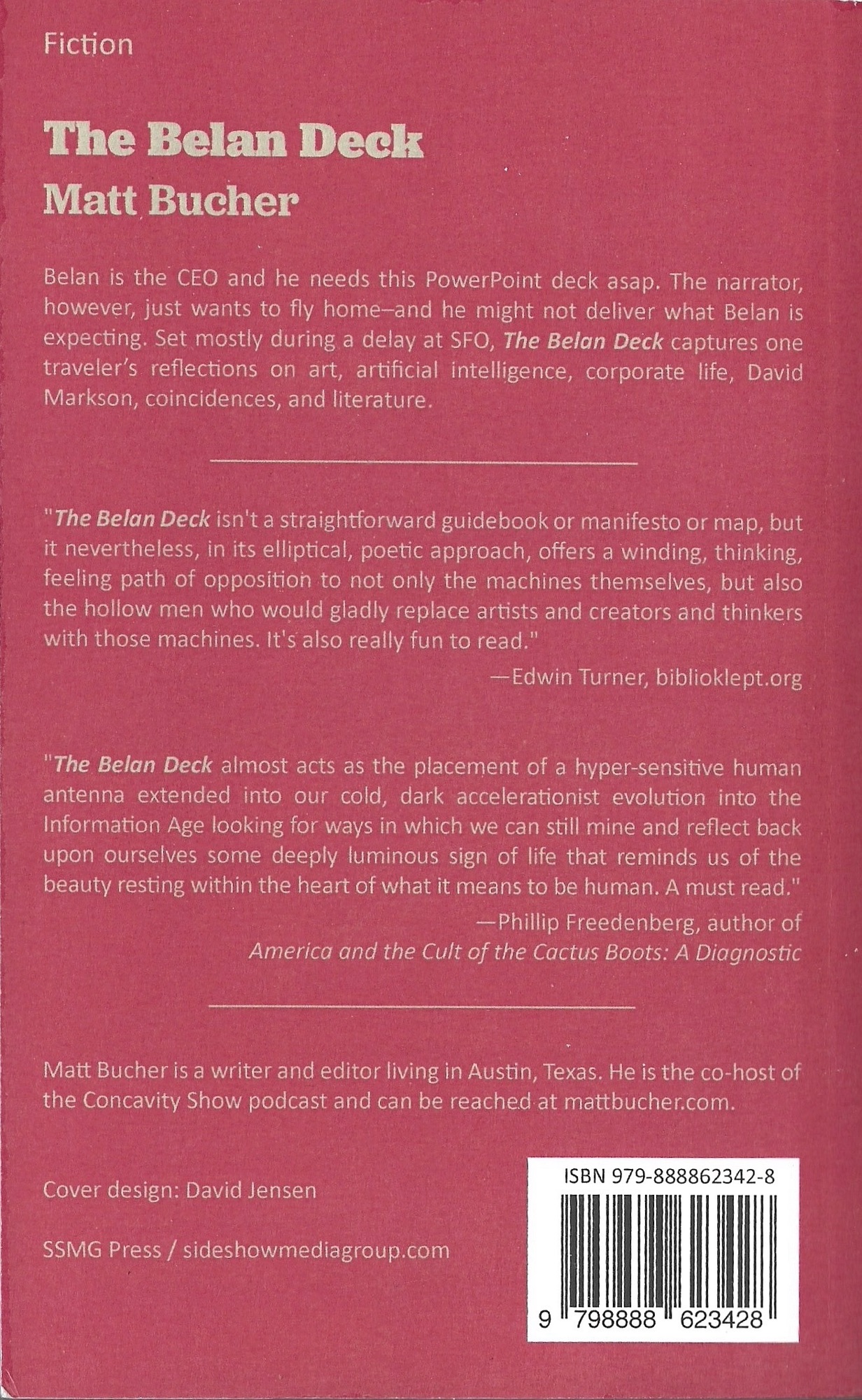

Ubik — Bob Pepper

Donald Barthelme’s Fine Homemade Soups

DONALD BARTHELME’S FINE HOMEMADE SOUPS

My fine homemade soups are interesting, economical, and tasty. To make them, one proceeds in the following way:

Fine Homemade Leek Soup

Take one package Knorr Leek Soupmix. Prepare as directed. Take two live leeks. Chop leeks into quarter-inch rounds. Throw into Soupmix.

Throw in ½ cup Tribuno Dry Vermouth. Throw in chopped parsley.

Throw in some amount of salt and a heavy bit of freshly-ground pepper.

Eat with good-quality French bread, dipped repeatedly in soup.

Fine Homemade Mushroom Soup

Take one package Knorr Mushroom Soupmix. Prepare as directed.

Take four large mushrooms. Slice. Throw into Soupmix. Throw in ⅛ cup Tribuno Dry Vermouth, parsley, salt, pepper. Stick bread as above into soup at intervals. Buttering bread enhances taste of the whole.

Fine Homemade Chicken Soup

Take Knorr Chicken Soupmix, prepare as directed, throw in leftover chicken, duck, or goose as available. Add enhancements as above.

Fine Homemade Oxtail Soup

Take Knorr Oxtail Soupmix, decant into same any leftover meat (sliced or diced) from the old refrigerator. Follow above strategies to the letter.

The result will make you happy. Knorr’s Oxtail is also good as a basic gravy-maker and constituent of a fine fake cassoulet about which we can talk at another time. Knorr is a very good Swiss outfit whose products can be found in both major and minor cities. The point here is not to be afraid of the potential soup but to approach it with the attitude that you know what’s best for it. And you do. The rawness of the vegetables refreshes the civilization of the Soupmixes. And there are opportunities for mercy-if your ox does not wish to part with his tail, for example, to dress up your fine Oxtail Soup, you can use commercial products from our great American supermarkets, which will be almost as good. These fine homemade recipes work! Use them with furious enthusiasm.

From The Great American Writers’ Cookbook (ed. Dean Faulkner Wells, 1981).

19 Nov. 2024 (Blog about missing GY!BE and Alan Sparhawk this weekend in Atlanta)

This is Friday—not today, I mean, this, this blog, is Friday, four or five days ago, depending on how you count such things. We were maybe fifteen or twenty minutes on the road heading northwest to Atlanta—my wife driving the first leg before we stopped for gas—when I checked social media again to see if Godspeed You! Black Emperor were still going to play that night. They were not. This information came via opener Low legend Alan Sparhawk, who had reported the past two nights’ shows canceled.

We headed north anyway. The kids had left school early; my daughter pointed out that she had already missed an AP Bio test and that she wasn’t going with me and the boy to the show anyway, she just wanted to go to Atlanta to hang out. Fair point, of course.

My son was bummed and I was bummed. I don’t know exactly how he came to Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s strange, hypnotic, droney anthems—via an algorithm, really—but a few years ago I heard him blasting Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven in his bedroom. I gave him my copy of their debut LP, F♯ A♯ ∞, which I’d bought from the band back in 1998 or 1999 when they opened for Low at a record story I was working at in Florida. They knocked our socks off. It seemed there were more Godspeeds Yous than audience members, and to be clear, the tiny record store was packed. It was a summer afternoon in Florida; very hot and very sunny, a throbbing miasma of sound across Hemming Park, now James Weldon Johnson Park, in beautiful ugly downtown Jacksonville.

(It was just such a night my friend Travis was arrested for skateboarding across Laura Street. Jayskating. (I don’t think it was the same night.))

After the show I bought their record. It had a pouch crammed with incidentals—flattened pennies, a Canadian stamp, some illustrated scraps. I think I listened to it a million times that summer. One of the guys in the band asked me where they could get some hash in Jacksonville. I suggested the Waffle House. Low played after; everyone sat down, exhausted from what Godspeed had required. It was lovely. Perfect day.

I had really wanted to experience my imaginative inversion of this concert this past weekend, but it didn’t emerge. I mean Alan Sparhawk, whose new record is so strange and daring and wonderful—I wanted to see that with my kid, who, he, my kid, wanted to see the ensemble Godspeed do their drone magic. I bought him an Aphex Twin record at Wax n’ Facts as a consolation prize, and he bought himself the first volume of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira at A Capella Books. I picked up a first edition hardback of William Gaddis’s last novel Agapē Agape.

And so well we made a weekend of it, browsing book stores and record stores and walking the Beltline. Love that city and my best wishes to GY!BE founding member, Efrim Menuck—I hate that we missed you on the tour but I hope that your health recovers. Thank you for making music my son and I love.

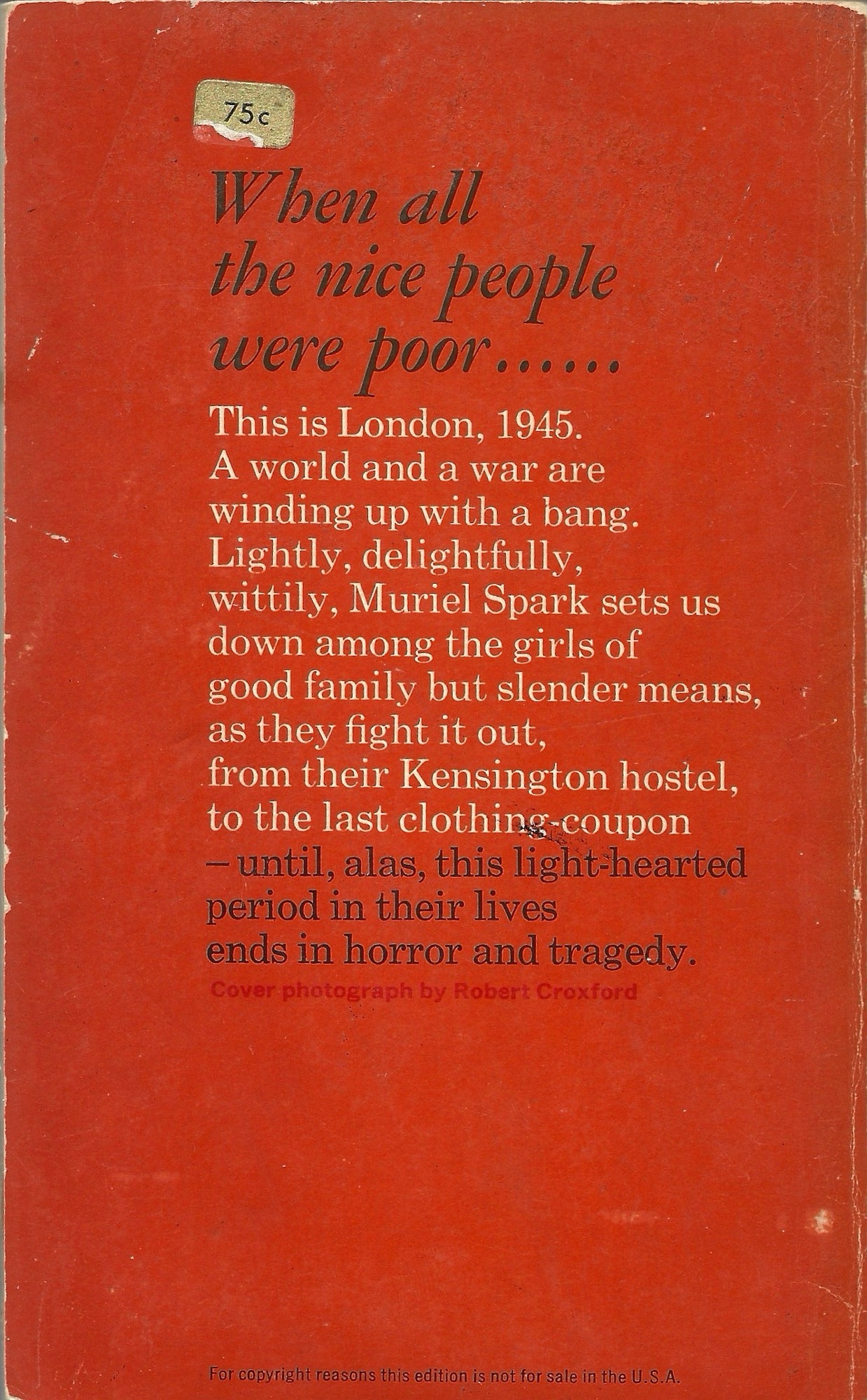

Mass-market Monday | Muriel Spark’s The Girls of Slender Means

The Girls of Slender Means, Muriel Spark. Penguin Books (1966). Cover photograph by Robert Croxford. 142 pages.

From a thing a wrote back in 2020:

Slender Means unself-consciously employs postmodern techniques to paint a vibrant picture of what the End of the War might feel like. The climax coincides with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the title takes on a whole new meaning, and the whole thing unexpectedly ends in a negative religious epiphany.

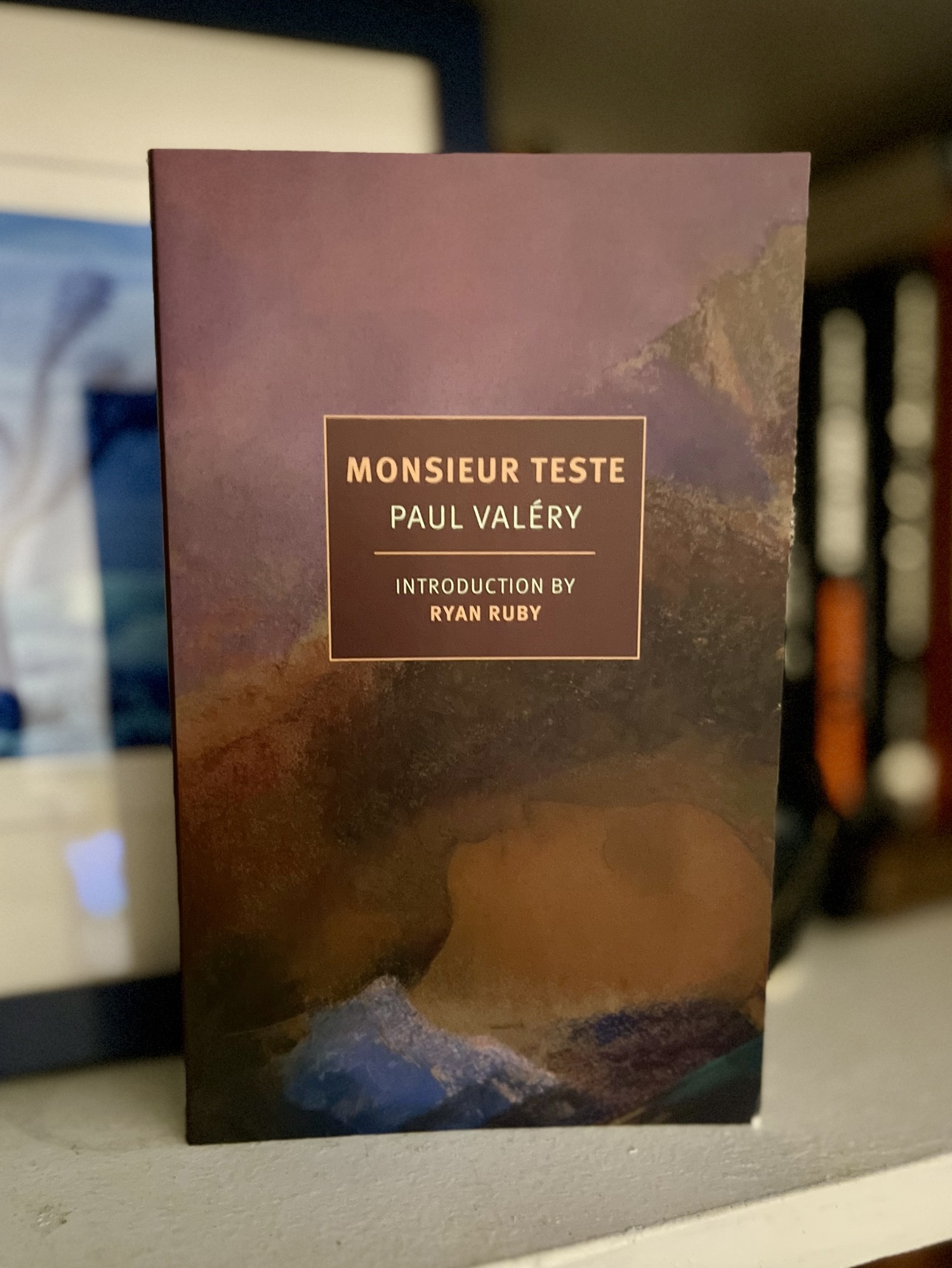

Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste (Book acquired, 14 Nov. 2024)

Got a review copy of Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste, a slim lil fellow from NYRB in translation by Charlotte Mandell. The back cover includes a blurb from William H. Gass—

Monsieur Teste is a monster, and is meant to be—an awesome, wholly individualized machine—yet in a sense he is also the sort of inhuman being Valéry aimed to become himself: a Narcissus of the best kind, a scientific observer of consciousness, a man untroubled by inroads of worldly trivia, who vacations in his head the way a Platonist finds his Florida in the realm of Forms.

What the fuck does Gass mean by “Florida” here? I really want to know.

This style of post, the book acquired post, is an established, which is to say tired, blog post format on this blog, Biblioklept, probably going back a decade now, born from a glut of review copies piling up, mostly unasked for but many asked for, books that stack up their own measures of guilt, unread, or then maybe read, months, years later—but the post style is ephemeral, yes, fluffy, sure, embarrassing even maybe. The form is stale; I apologize. I do think the Valéry book seems pretty cool.

I have a not-insubstantial stack of newly acquired new (and used books) stacked on the cherry side table by the black leather couch that I should have made book acquired posts about. These have piled up over the last few weeks. These are not interesting sentences (several of the books seem very interesting).

I am not going to find the new form I want here, am I?

When I was a freshman in high school, my then-girlfriend’s older brother gave me a mixtape that a girl had given him. He didn’t like anything on the mixtape; he liked Buddy Holly. I can’t remember why he gave me the tape—I think I saw it in his car and asked about it. But it ended up changing my life in some ways, as small giant things like songs or books or films can do when they come over you at the right time and place.

There were a few bands on the tape that I knew or had heard of, and even some I owned albums by, like the Cure and the Smiths. But for the most part, the tape opened a new aural world to me. I heard My Bloody Valentine, Big Star, Ride, the Cocteau Twins, and This Mortal Coil, among others, for the first time. There were also two songs by one band: Slowdive’s “When the Sun Hits” and “Dagger.”

(This particular blog post is no longer about acquiring a Valéry translation; it is about something else.)

Those songs are from Slowdive’s 1993 classic Souvlaki. I owned it on cassette. That cassette melted, just slightly, on the top of my 1985 Camry’s dashboard in like August of 1995. The tape was just warped enough not to fit into a cassette deck. I liked to imagine how it would sound. The next year, my lucky privileged ass found a used CD of Slowdive’s follow-up, Pygmallion on a school trip to London. Slowdive kinda sorta broke up after that.

I have always been a proponent of bands breaking up. I think a decade is long enough; get what you need done in five or six albums and move on. There are many many exceptions to this rule. But generally, I don’t think beloved bands—by which I means bands beloved by me—should keep going on too long. And if they break up, they should stay broken.

But I bought Slowdive’s 2017 reunion album Slowdive used at a St. Petersburg record store and listened to it again and again, amazed at how strong it was, how true to form. My kids liked it a lot. And then they put out a record last year, Everything Is Alive—I like that one too (not as good as the self titled one).

(There’s no point to any of this; I might’ve had some wine; I might just feel like writing.)

I guess if you’d told me back in ’95 or ’05 or even ’15 that I’d see a reunited Slowdive twice in one year I’d say that that sounded silly. (The ’15 version of me that had seen Dinosaur Jr.’s dinosaur act wouldn’t have been interested.) But we went out into the woods to see Slowdive this Sunday. They played the St. Augustine Amphitheatre to a large, strange, diverse crowd, out there in the Florida air. A band named Wisp, TikTok famous I’m told, opened, and they were pretty good. But Slowdive was perfect—better than back in May in Atlanta—echo and reverb ringing out into Anastasia State Park.

We stayed in a cheap motel off of AIA that night—another sign of my age. When I was younger, I could drive six hours, watch a band, and drive the six hours back without blinking. We are about 45 minutes from St. Augustine. It was a nice night out.

A younger version of me could’ve read the 80 pages of Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste in the time it took to twiddle my thumbs in this post and write a real (and likely bad) review to boot. Again, apologies. I’m getting old, a dinosaur act. But I can’t break up, not now.

Slowdive, St. Augustine Amphitheatre, 10 Nov. 2024

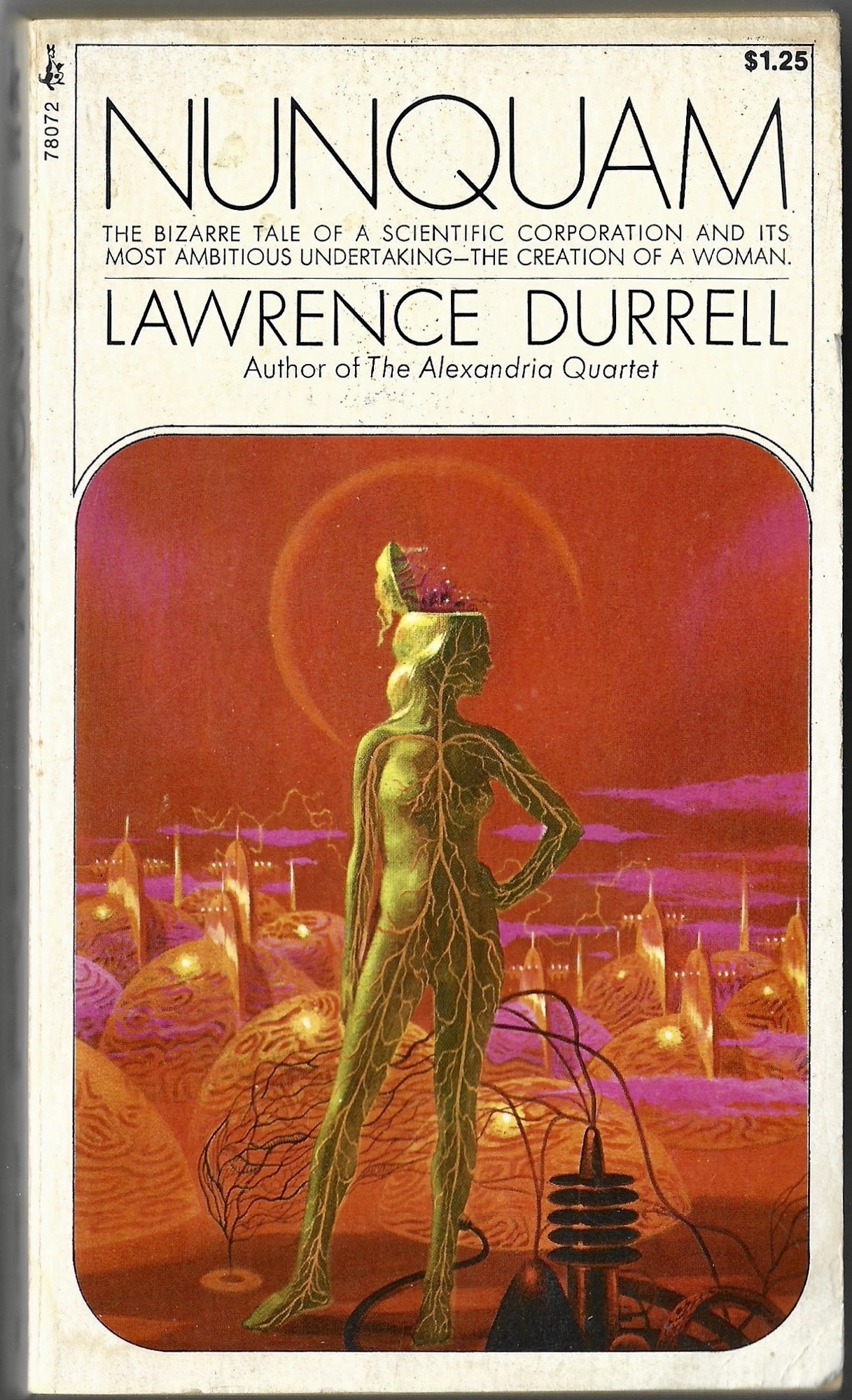

Slowdive, St. Augustine Amphitheatre, 10 Nov. 2024Mass-market Monday | Lawrence Durrell’s Nunquam

Donald Barthelme’s Forty Stories in reverse, Part I

A few years ago, I reread Donald Barthelme’s collection Sixty Stories and wrote about them on this blog. I enjoyed the project immensely. A recent comment on the last of those Sixty Stories posts asked, or demanded, I suppose (the four-word comment is in the imperative voice) that I Now do Forty Stories. Which I am going to now do, Forty Stories.

40. “January” (first published in The New Yorker, 6 April 1987)

“January” begins as a dialogue between two characters, a mode Barthelme would return to repeatedly throughout his later career. The story is ostensibly a Paris Review style interview with one “Thomas Brecker,” who has authored seven books on religion over his thirty-five year career. The story begins as light satire; our Serious Writer is “renting a small villa” in St. Thomas; the interviewer notes that “a houseboy attended us, bringing cool drinks on a brown plastic tray of the sort found in cafeterias.” The interview quickly takes the shape of a career-spanning reflection, with Brecker sliding into a more melancholy mind frame. By the end of the story, the “interviewer” disappears, leaving us in Brecker’s imagination, where we have likely always been, and it’s hard not to read Barthelme’s autobiographical flourishes beneath Brecker’s mordant quips:

I think about my own death quite a bit, mostly in the way of noticing possible symptoms—a biting in the chest—and wondering, Is this it? It’s a function of being over sixty, and I’m maybe more concerned by how than when. That’s a … I hate to abandon my children. I’d like to live until they’re on their feet. I had them too late, I suppose.

39. “The Baby” (Overnight to Many Distant Cities, 1983)

“The Baby” was composed around the same time as “Chablis” (1983); both stories are love letters of paternal affection for an infant daughter. Again, it’s hard not to see Barthelme’s own biography here. His daughter Katherine was an infant at the time he wrote them. While I don’t think “The Baby” is as strong as “Chablis” is (or, at least as strong in my memory — “Chablis” is the first story in Forty Stories, so we’ll get there, I guess) — while I don’t think “The Baby” is as strong as “Chablis,” it’s still a fun little ditty with an anarchic punchline. It’s also, like barely five short paragraphs–just read it.

38. “Great Days” (Great Days, 1979)

As I revisit my notes for “Great Days,” I realize I should probably read the story again, more slowly, and try to tune more into its voice. Or voices. Are there two voices here, or one? I think there is more of a n actual story story here than I can summarize — not that anyone wants summary of Barthelme — but my takeaway is that this is Barthelme doing Stein doing Cubism doing… In his 2009 biography of Barthelme Hiding Man, Tracy Daugherty wrote that New Yorker fiction editor (and early Barthelme champion) Roger Angell rejected an early version of the story (under the title “Tenebrae”). According to Daugherty’s bio, while Angell recognized the story as a “serious work” and a “new form,” he ultimately thought it was too “private and largely abstract” for publication.

I think this bit is lovely read aloud:

—Purple bursts in my face as if purple staples had been stapled there every which way—

—Hurt by malicious criticisms all very well grounded—

—Oh that clown band. Oh its sweet strains.

—The sky. A rectangle of glister. Behind which, a serene brown. A yellow bar, vertical, in the upper right.

—I love you, Harmonica, quite exceptionally.

—By gum I think you mean it. I think you do.

—It’s Portia Wounding Her Thigh.

—It’s Wolfram Looking at His Wife Whom He Has Imprisoned with the Corpse of Her Lover.

37. “Letters to the Editore” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

A lively little gem from Barthelme’s mid-seventies “non-fiction” collection Guilty Pleasures. Its inclusion seems to show an editorial need to pad out Forty Stories with more hits than the old boy had strung together by ’87. Anyway. “Letters to the Editore” is a fantastic send-up of small aesthetic aggressions writ large in the slim pages of little magazines. The ostensible subject is a dust-up surrounding an exhibition of so-called “asterisk” paintings by an American in a European gallery—but the real subject is language itself:

The Editor of Shock Art has hardly to say that the amazing fecundity of the LeDuff-Galerie Z controversy during the past five numbers has enflamed both shores of the Atlantic, at intense length. We did not think anyone would care, but apparently, a harsh spot has been touched. It is a terrible trouble to publish an international art-journal in two languages simultaneously, and the opportunities for dissonance have not been missed.

Barthelme’s comedic control of voices here is what makes this “story” an early (which is to say, late) standout in Forty Stories. It is the “opportunities for dissonance” that our author is most interested in and attuned to.

36. “Construction” (first published in The New Yorker, 21 April 1985)

“Construction” is the non-story of a writer flying out West to complete the “relatively important matter of business which had taken me to Los Angeles, something to do with a contract, a noxious contract, which I signed.” The documents he signs are “reproduced on onionskin, which does not feel happy in the hand.” This is one of two decent verbal flares in “Construction”; the other is an extended episode (as verbal flare-ups go) in which we find our Writer-Hero up against the wall of absurdity:

The flight back from Los Angeles was without event, very calm and smooth in the night. I had a cup of hot chicken noodle soup which the flight attendant was kind enough to prepare for me; I handed her the can of chicken noodle soup and she (I suppose, I don’t know the details) heated it in her microwave oven and then brought me the cup of hot chicken noodle soup which I had handed her in canned form, also a number of drinks which helped make the calm, smooth flight more so. The plane was half empty, there had been a half-hour delay in getting off the ground which I spent marveling at a sentence in a magazine, the sentence reading as follows: “[Name of film] explores the issues of love and sex without ever being chaste.” I marveled over this for the full half-hour we sat on the ground waiting for clearance on my return from Los Angeles, thinking of adequate responses, such as “Well we avoided that at least,” but no response I could conjure up was equal to or could be equal to the original text which I tore out of the magazine and folded and placed, folded, in my jacket pocket for further consideration at some time in the future when I might need a giggle.

Barthelme’s stand-in confesses here to what we’ve always known: He’s a scissors-and-paste man, a night ripper with a good ear, a good eye, but mostly one of us, a guy who needs a good giggle.

RIP Robert Coover, Prince of American Metafiction

RIP Robert Coover, 1932-2024

Robert Coover passed away a few days ago at ninety-two years old. In his decades-spanning career, Coover published twenty-one novels, four plays, and four short story collections. He also published dozens of (as-yet) uncollected stories, essays, and a host of so-called “electronic fiction.” A fifth short story collection, 2018’s Going for a Beer, collected some of Coover’s greatest hits, and is generally an excellent starting place for those interested in Coover’s metatextual fabulism.

Coover didn’t start out as a metatextual fabulist. His first novel, 1966’s The Origin of the Brunists, is vivid, humanist realism with the slightest tinges of magic brightening its edges. 1968’s follow-up, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., strays much deeper into the pop-myth fantasies that Coover would perfect in his mature career.

Coover’s 1969 collection Pricksongs & Descants shows a remarkable shift into postmodern metafiction. Pricksongs features some of his better stories, like “The Brother” (told from the point of view of the biblical Noah’s brother), “The Elevator,” and “The Magic Poker,” which begins with the sentence “I wander the island, inventing it” — a tidy encapsulation of Coover’s growing motif of the self-creating story. At times, this metatextual motif can exhaust the reader, as in Pricksongs’ capper “The Hat Act.” However, the collection features one of Coover’s best stories, “The Babysitter,” in which the titular character serves as a locus for a mundane suburban community’s collective repressed anxieties of sex and violence.

Coover would continue to explore such themes throughout his career, refining and sharpening his metatextual hat act in standout novels like Spanking the Maid (1982), Gerald’s Party (1986), and 1977’s The Public Burning—arguably Coover’s most important novel. It’s easy to think of The Public Burning as the last part of a loose postmodern American trilogy of large daring novels, the first two parts comprised of Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and William Gaddis’s J R (1975).

Indeed, Coover was regularly grouped with a (very white, very male) clique of postmodern American writers. In his 1980 essay “The Literature of Replenishment,” John Barth halfheartedly counted up the members: “By my count, the American fictionists most commonly included in the canon, besides the three of us at Tubingen [William H. Gass, John Hawkes and Barth himself], are Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkin, Thomas Pynchon, and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.”

There was some chatter on social media that Coover’s passing left just Pynchon–and maybe Don DeLillo and Joseph McElroy–as the last living luminaries of twentieth-century US American postmodernist fiction. Of course, Pynchon really wasn’t a member of this or any other clique (he declined an invitation to Donald Barthelme’s so-called “postmodernists dinner“), and, as is too often the case with such groupings, Ishmael Reed’s contribution to American postmodernist fiction continues to be marginalized.

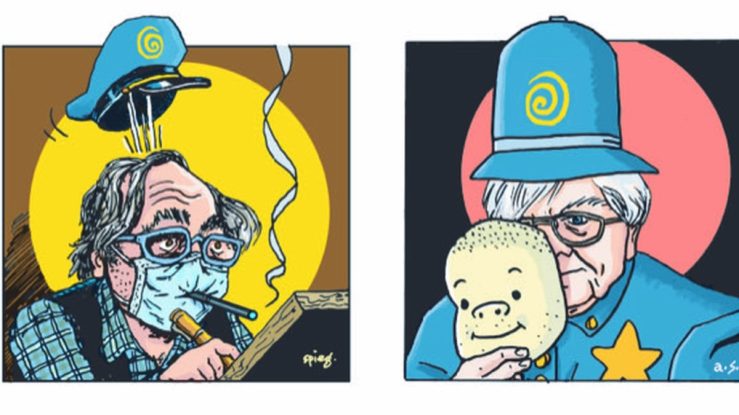

Let it stand then that Robert Coover, despite whatever connections and friendships he held with other writers and artists, was his own special self-made creation. He was prolific, especially later in life, publishing nine novels in the twenty-first century. One of these was The Brunist Day of Wrath (2014), a sequel to his debut; he also collaborated with comix artist Art Spiegelman on the graphic novelette Street Cop (2021) and even found a sliver of mainstream readers with Huck Out West, his wonderful 2017 “sequel” to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Coover’s latest novel Open House was published just over a year ago.

Clearly, Coover leaves behind a large body of work, and we’ll likely see more of his work collected and published over the next decade. I won’t pretend to have read most of what he’s written, but I’ve loved a lot of it—particularly Pricksongs & Descants, Huck Out West, Spanking the Maid, and Briar Rose, which, as far as I can recall, is likely the first thing I read of his (my girlfriend at the time’s sister had to read it in college; she professed that she hated it but thought I’d like it). The aforementioned 2018 collection Going for a Beer is a nice starting place for Coover; those more interested in novels might like Spanking the Maid. Or jump into one of his later short novels, like 2004’s Stepmother or 2018’s The Enchanted Prince, both of which exemplify his metamagicianist mode. Or hell, just go for the big boy, The Public Burning. Ultimately, Coover leaves behind a trove of trembling, writhing, vividly-living words, an oeuvre that will continue to engage readers fascinated by a certain stamp of so-called experimental literature–and for that I thank him.

Mass-market Monday | Robert Coover’s The Origin of the Brunists

The Origin of the Brunists, Robert Coover. Banatm Books Edition (1978). No cover designer credited. 534 pages.

This Bantam reprint of Coover’s first novel coincided with their mass-market paperback publication of The Public Burning.

I wrote a bit on The Origin of the Brunists a few years back. From that riff:

Coover’s metafiction always points back at its own origin, its own creation, a move that can at times take on a winking tone, a nudging elbow to the reader’s metaphorical ribs—Hey bub, see what I’m doing here? Coover’s metafictional techniques often lead him and his reader into cartoon landscapes, where postmodernly-plastic characters bounce manically off realistic contours. The best of Coover’s metafictions (like “The Babysitter,” 1969) tease their postmodern plastic into a synthesis of character, plot, and theme. However, in large doses Coover’s metafictions can tax the reader’s patience and will—the simplest example that comes to mind is “The Hat Act” (from Pricksongs & Descants, 1969), a seemingly-interminable Möbius loop that riffs on performance, trickery, and imagination. (And horniness).

I’m dwelling on Coover’s metafictional myth-making because I think of it as his calling card. And yet Origin of the Brunists bears only the faintest traces of Coover’s trademark metafictionalist moves (mostly, so far anyway, by way of its erstwhile hero, the journalist Tiger Miller). Coover’s debut reads rather as a work of highly-detailed, highly-descriptive realism, a realism that pushes its satirical edges up against the absurdity of modern American life. It reminds me very much of William Gass’s first novel Omensetter’s Luck (1966) and John Barth’s first two novels, The Floating Opera (1956) and The End of the Road (1958). (Barth heavily revised both of the novels in 1967). There’s a post-Faulknerian style here, something that can’t rightly be described as modern or postmodern. These novels distort reality without rupturing it in the way that the authors’ later works do. Later works like Barth’s Chimera (1973), Gass’s The Tunnel (1995), and Coover’s The Public Burning (1977) dismantle genre structures and tropes and rebuild them in new forms.

We have the right to convey the fictive of any reality at all | Gil Orlovitz

We have the right to convey the fictive of any reality at all–and there is nothing that is not real—by any method we wish, and to have as our goal, if we so opt, only that we maintain the reader’s tension, the solitary indication, itself mercurial, of a work-of-art event.

Syntax being nothing more nor less than the codification of selected usages, we may alter syntax or reject it wholly.

We may compose the fictive in such a manner that the result is ambiguous, baffling and sometimes altogether impossible significantly to paraphrase-but so long as the piece seizes and holds the reader, a basic meaning, impossible to state in language as we know it, has been established, a meaning that belongs to a time series of seizing-and-holding.

The notion, we submit, of clarity, remains simply a notion, real enough, of course, under whatever category it is sub-sumed, but of no universal vigor, necessarily, nor marked by socalled objective truth; clarity is a notion identifying a particular social agreement in a one-to-one sense as to what construct evokes similarity of analysis.

Empirically all that is demonstrable is that we experience as creator or audience a series of perceptions. Now, if we set forth that demonstration in the fictive in such a fashion as to generate and sustain tension in the reader whether or not he is mystified by the significs, we have met the sole possible criterion.

We are not of course here in any way concerned with the alleged scalar values of a given fiction-the notion of value belongs to ad hominen pleaders usually involved in depressing or elevating a status for economic reasons—just as we cannot in any way be concerned with the alleged scalar values of the given reader. Fiction and reader are conjoined, and may not with any sense be disjunct if we are trying to penetrate the nature of the esthetic.

Such being the case, I believe we can with some innocence look at the choices of the contemporary avant-garde herein, and digest them according to our lights or chiaroscuras.

We need remember only how much more we usually discern if we take the trouble, to begin with, to clean our own canvasses-within reason.

—Gil Orlovitz

Gil Orlovitz’s introduction to The Award Avant-Garde Reader (1965).

The Scalphunters | An excerpt from an early draft of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian

The Spring 1980 issue of Northwestern University’s literary journal TriQuarterly included an early version of a chapter from Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. The TriQuarterly excerpt, published as “The Scalphunters,” is essentially Ch. XII of the finished 1985 Random House publication of Blood Meridian with some minor differences.

Consider, for example, the following paragraph–the seventh paragraph in “The Scalphunters” —

When the company set forth in the evening they continued south as before. The tracks of the murderers bore on to the west but they were white men who preyed on travelers in that wilderness and disguised their work in this way. The trail of the argonauts of course went no further than the ashes they left behind and the intersection of these vectors seemed the work of a cynical god, the traces converging blindly in that whited void and the one going on bearing away the souls of the others with them.

McCarthy significantly expands the passage in his final revision, underscoring Blood Meridian’s theme of witnessing:

When the company set forth in the evening they continued south as before. The tracks of the murderers bore on to the west but they were white men who preyed on travelers in that wilderness and disguised their work to be that of the savages. Notions of chance and fate are the preoccupation of men engaged in rash undertakings. The trail of the argonauts terminated in ashes as told and in the convergence of such vectors in such a waste wherein the hearts and enterprise of one small nation have been swallowed up and carried off by another the expriest asked if some might not see the hand of a cynical god conducting with what austerity and what mock surprise so lethal a congruence. The posting of witnesses by a third and other path altogether might also be called in evidence as appearing to beggar chance, yet the judge, who had put his horse forward until he was abreast of the speculants, said that in this was expressed the very nature of the witness and that his proximity was no third thing but rather the prime, for what could be said to occur unobserved?

Perhaps the most jarring difference though is that in “The Scalphunters” McCarthy refers to his erstwhile protagonist not as the kid but as the boy. Here’s a longish passage from The TriQuarterly edit to give you a taste of that flavor:

Brown let the belt fall from his teeth. Is it through? he said.

It is.

The point? Is it the point? Speak up, man.

The boy drew his knife and cut away the bloody point deftly and handed it up. Brown held it to the firelight and smiled. The point was of hammered copper and it was cocked in its blood-soaked bindings on the shaft but it had held.

Stout lad, ye’ll make a shadetree sawbones yet. Now draw her.

The boy withdrew the shaft from the man’s leg smoothly and the man bowed on the ground in a lurid female motion and wheezed raggedly through his teeth. He lay there a moment and then he sat up and took the shaft from the boy and threw it in the fire and rose and went off to make his bed.

When the boy returned to his own blanket the ex-priest Tobin leaned to him and looked about stealthily and hissed at his ear.

Fool, he said. God will not love ye forever.

The boy turned to look at him.

Dont you know he’d of took you with him? He’d of took you, boy. Like a bride to the altar.

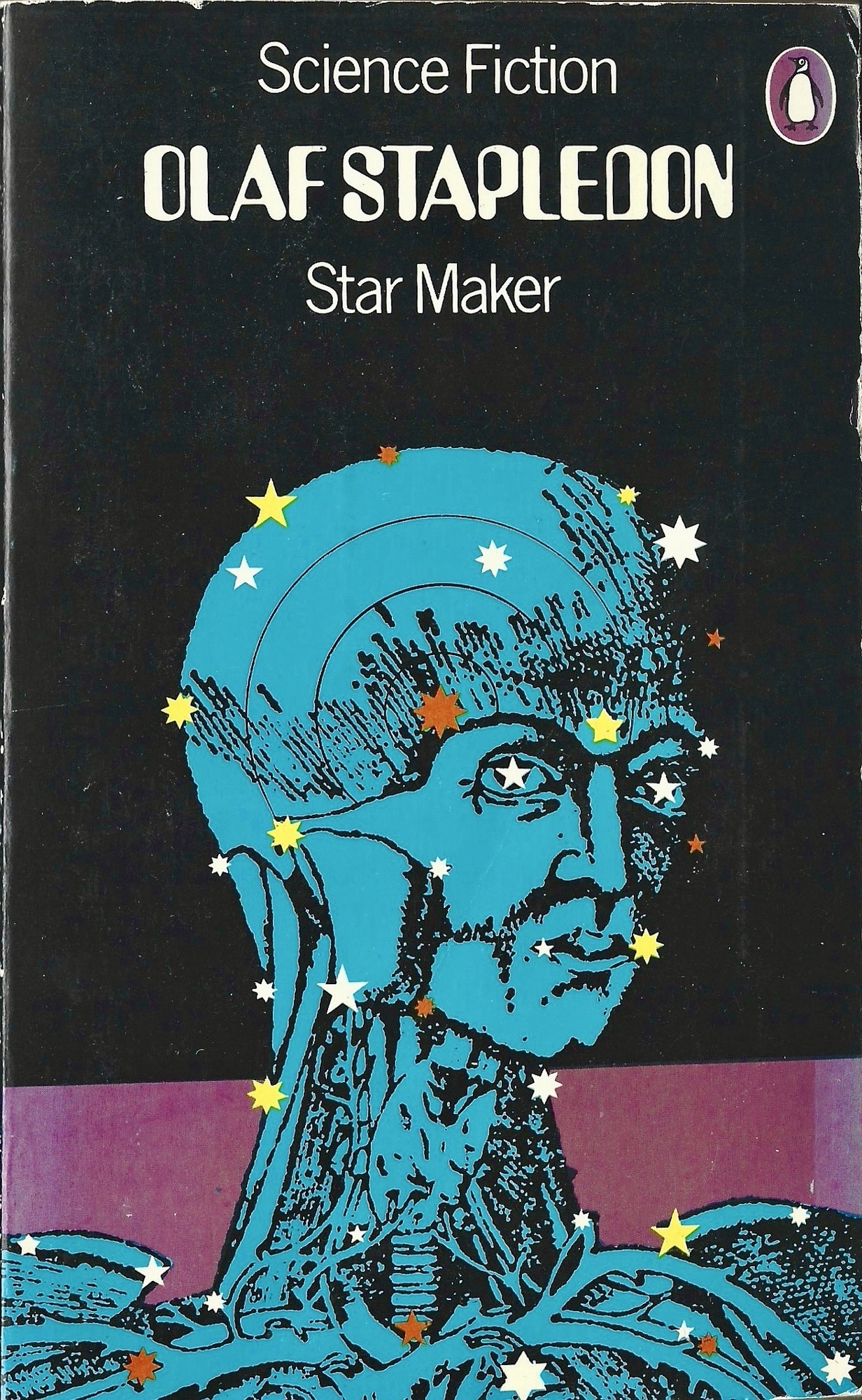

Mass-market Monday | Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker

Star Maker, Olaf Stapledon. Penguin Books (1973). Cover design by David Pelham. 268 pages.

Here is the first paragraph of Star Maker:

ONE night when I had tasted bitterness I went out on to the hill. Dark heather checked my feet. Below marched the suburban lamps. Windows, their curtains drawn, were shut eyes, inwardly watching the lives of dreams. Beyond the sea’s level darkness a lighthouse pulsed. Overhead, obscurity. I distinguished our own house, our islet in the tumultuous and bitter currents of the world. There, for a decade and a half, we two, so different in quality, had grown in and in to one another, for mutual support and nourishment, in intricate symbiosis. There daily we planned our several undertakings, and recounted the day’s oddities and vexations. There letters piled up to be answered, socks to be darned. There the children were born, those sudden new lives. There, under that roof, our own two lives, recalcitrant sometimes to one another, were all the while thankfully one, one larger, more conscious life than either alone.

More David Pelham covers here.

Afterword — Chester Arnold

Afterword, 2009 by Chester Arnold (b. 1952)