In his 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy said, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” McCarthy’s fourth novel, 1979’s Suttree is such a book, a masterful synthesis of the great literature — particularly American literature — that came before it. And like any masterful synthesis, Suttree points to something new, even as it borrows, lifts, and outright steals from the past. But before we plumb its allusions and tropes and patterns, perhaps we should overview the plot, no?

The novel rambles over several years in the life of Cornelius Suttree. It is the early 1950s in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Suttree ekes out a mean existence on the Tennessee River as a fisherman, living in a ramshackle houseboat on the edge of a shantytown. This indigent life is in fact a choice: Suttree is the college-educated son of an established, wealthy family. His choice is a choice for freedom and self-reliance, those virtues we like to think of, in our prejudicial manner, as wholly and intrinsically American. Suttree then is both Emersonian and Huck Finnian, a reflective and insightful man who finds his soul via a claim to agency over his own individuality, an individuality poised in quiet, defiant rebellion against the conforming forces of civilization. These forces manifest most pointedly in the Knoxville police, a brutal, racist organization, but we also see social constraint in the form of familial duty. One thinks of the final lines of Huckleberry Finn: “I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can’t stand it. I been there before.”

Like Huck, Suttree aims to resist all forces that would “sivilize” him. His time on the river and in the low haunts of Tennessee (particularly the vice-ridden borough of McAnally) brings him into close contact with plenty of other outcasts, but also his conscience, which routinely mulls over its place in the world. Suttree is punctuated by–perhaps even organized by–several scenes of hallucination. Some of these psychotrips result from drunkeness, one comes from accidentally ingesting the wrong kind of mushrooms (or, the right kind, if that’s your thing), and the final one, late in the novel, sets in as Suttree suffers from a terrible illness. In his fever dream, a small nun–surely a manifestation of the guilt that would civilize us–accuses him–

Mr. Suttree it is our understanding that at curfew rightly decreed by law in that hour wherein night draws to its proper close and the new day commences and contrary to conduct befitting a person of your station you betook yourself to various low places within the shire of McAnally and there did squander several ensuing years in the company of thieves, derelicts, miscreants, pariahs, poltroons, spalpeens, curmudgeons, clotpolls, murderers, gamblers, bawds, whores, trulls, brigands, topers, tosspots, sots and archsots, lobcocks, smellsmocks, runagates, rakes, and other assorted and felonious debauchees.

The passage is a marvelous example of McCarthy’s stream-of-consciousness technique in Suttree, moving through the various voices that would ventriloquize Suttree, into the edges of madness, strangeness, and the sublimity of language. The tone moves from somber and portentous into bizarre imagery that blends humor and pathos. This is the tone of Suttree, a language that gives voice to transients and miscreants, affirming the dignity of their humanity even as it details the squalor of their circumstance.

It is among these criminals and whores, transvestites and gamblers that Suttree affirms his own freedom and humanity, a process aided by his comic foil, Gene Harrogate. Suttree meets Harrogate on a work farm; the young hillbilly is sent there for screwing watermelons. After his release, Harrogate moves to a shantytown in Knoxville. He’s the country mouse determined to become the city rat, the would-be Tom Sawyer to Suttree’s older and wiser Huck Finn. Through Harrogate’s endless get-rich-quick schemes, McCarthy parodies that most-American of tales, the Horatio Alger story. Simply put, the boy is doomed, on his “way up to the penitentiary” as Suttree constantly admonishes. In one episode, Harrogate tries to buy arsenic from “a grayhaired and avuncular apothecary” to poison bats he hopes to sell to a hospital (don’t ask)–

May I help you? said the scientist, his hands holding each other.

I need me some strychnine, said Harrogate.

You need some what?

Strychnine. You know what it is dont ye?

Yes, said the chemist.

I need me about a good cupful I reckon.

Are you going to drink it here or take it with you?

Shit fire I aint goin to drink it. It’s poisoner’n hell.

It’s for your grandmother.

No, said Harrogate, craning his neck suspectly. She’s done dead

Suttree, unwilling father-figure, eventually buys the arsenic for the boy against his better judgment. The scene plays out as a wonderful comic inversion of William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” from which it is so transparently lifted. McCarthy borrows liberally from Faulkner here, of course, most notably in the language and style of the novel, but also in scenes like this one, or a later episode that plays off Faulkner’s comic-romantic story of a man and a woman navigating the aftermath of a flood, “Old Man.” Unpacking the allusions in Suttree surpasses my literary knowledge or skill, but McCarthy is generous, if oblique, with his breadcrumb trail. Take, for example, the following sentence: “Suttree with his miles to go kept his eyes to the ground, maudlin and muttersome in the bitter chill, under the lonely lamplight.” The forced phrase “miles to go” does not immediately present itself as a reference to Robert Frost’s famous poem, yet the direction of the sentence retreats into the history of American poetry; with its dense alliteration and haunted vowels, it leads us into Edgar Allan Poe territory. Only a few dozen pages later, McCarthy boldly begins a chapter with theft: “In just spring the goatman came over the bridge . . .” The reference to e.e. cummings explicitly signifies McCarthy’s intentions to play with literature. Later in the book, while tripping on mushrooms in the mountains, Suttree is haunted by “elves,” the would-be culprits in Frost’s poem “Mending Wall.” The callback is purposeful, but tellingly, McCarthy’s allusions are not nearly as fanciful as their surface rhetoric might suggest: the goatman does not belong in Knoxville–he’s an archaic relic, forced out of town by the police; the elves are not playful spirits but dark manifestations of a tortured psyche.

Once one spots the line-lifting in Suttree it’s hard to not see it. What’s marvelous is McCarthy’s power to convert these lines, these riffs, these stories, into his own tragicomic beast. An early brawl at a roadhouse recalls the “Golden Day” episode of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; a rape victim’s plight echoes Hubert Selby’s “Tralala”; we find the comic hobos of John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row–we even get the road-crossing turtle from The Grapes of Wrath. A later roadhouse chapter replays the “Circe/Nighttown” nightmare in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Ulysses is an easy point of comparison for Suttree, which does for Knoxville what Joyce did for Dublin. Suttree echoes Ulysses’s language, both in its musicality and appropriation of varied voices, as well as its ambulatory structure, its stream-of-consciousness technique, its rude earthiness, and its size (nearly 600 pages). But, as I argued earlier, there’s something uniquely American about Suttree, and its literary appropriations tend to reflect that. Hence, we find Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, Walt Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, and William Carlos Williams, to name just a few writers whose blood courses through this novel (even elegant F. Scott Fitzgerald is here, in an unexpected Gatsbyish episode late in the novel).

Making a laundry list of writers is weak criticism though, and these sources–all guilty of their own proud plagiarisms–are mentioned only as a means to an end, to an argument that what McCarthy does in Suttree is to synthesize the American literary tradition with grace and humor, while never glossing over its inherent dangers and violence. So, while it appropriates and plays with the tropes of the past, Suttree is still pure McCarthy. Consider the following passage, which arrives at the end of a drunken, awful spree, Suttree locked up for the night–

He closed his eyes. The gray water that dripped from him was rank with caustic. By the side of a dark dream road he’d seen a hawk nailed to a barn door. But what loomed was a flayed man with his brisket tacked open like a cooling beef and his skull peeled, blue and bulbous and palely luminescent, black grots his eyeholes and bloody mouth gaped tonguless. The traveler had seized his fingers in his jaws, but it was not alone this horror that he cried. Beyond the flayed man dimly adumbrate another figure paled, for his surgeons move about the world even as you and I.

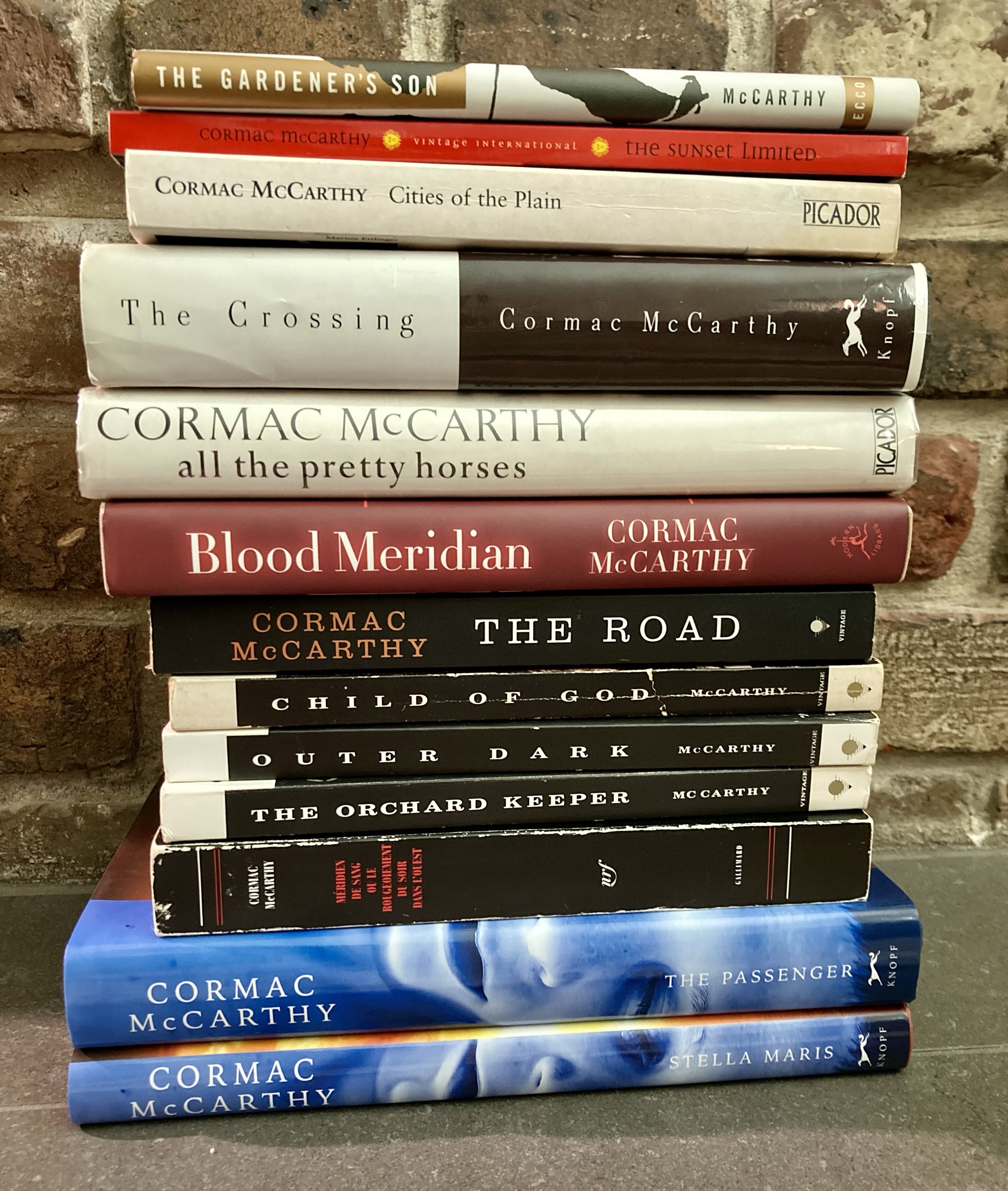

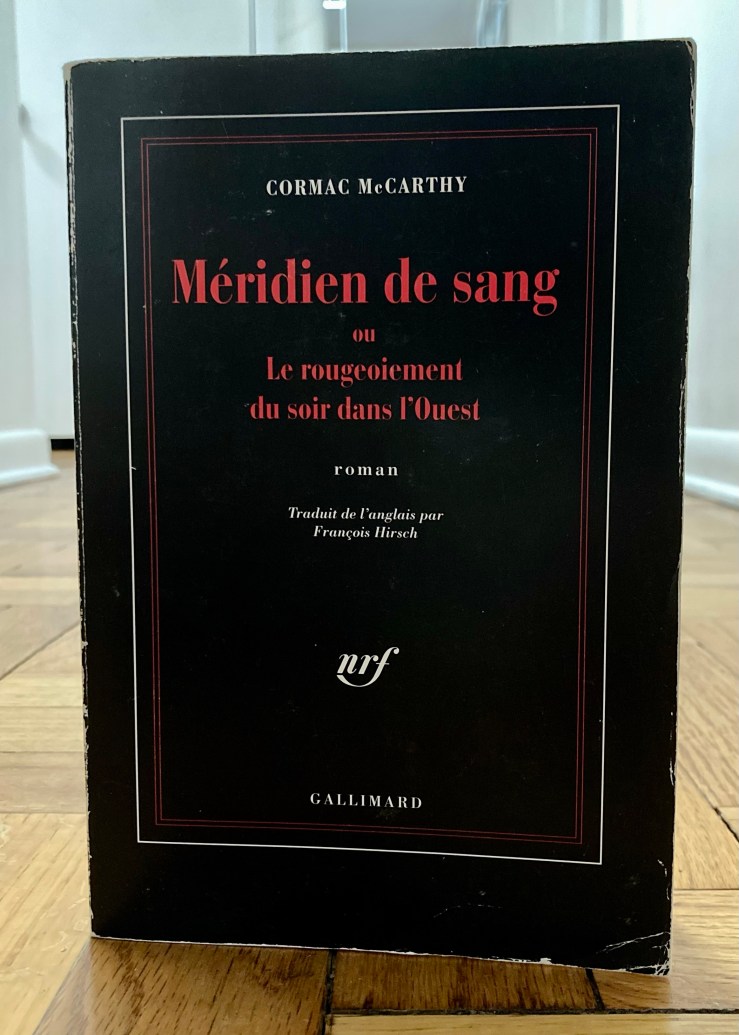

Suttree’s dark vision points directly toward the language of McCarthy’s next novel, 1985’s Blood Meridian, roundly considered his masterpiece. Critics who disagree tend to point to Suttree as the pinnacle of McCarthy’s writing. I have no interest at this time in weighing the books against each other, nor do I think that doing so would be especially enlightening. For all of their sameness, they are very different animals: Suttree provides us intense access to its hero’s consciousness, where Blood Meridian always keeps the reader on the outside of its principals’ souls (if those grotesques could be said to have souls). And while Blood Meridian does display some humor, it is the blackest and driest humor I’ve ever read. Suttree is broader and more compassionate; it even has a fart joke. Blood Meridian, at least in my estimation (and many critics will contend this notion) has no flawed episodes; much of this results from the book’s own internal program–it resists love, compassion, and even human dignity. In contrast, Suttree is punctuated by two deaths the audience is meant to read as tragic, yet I found it impossible to do so. The first is the death of Suttree’s child, whom he has abandoned, along with its mother. As such, he is not permitted to take part in the funeral, observing the process rather from its edges. The second tragedy is the death of Suttree’s young lover in a landslide. The book begs us to empathize with Suttree, just as he often empathizes with the marginal figures in the novel, but ultimately these tragedies are a failed ploy. They underwrite a sublime encounter with death for Suttree, an encounter that deepens and enriches his character while paradoxically freeing him from the burdens of social duty and familial order. McCarthy is hardly alone in such a move; indeed, it seems like the signature trope of American masculine literature to me. It’s the move that Huck Finn wishes to make when he promises to light out for the Territory to escape the civilizing body of Aunt Sally; it’s the ending that Hemingway was compelled to give to Frederic Henry at the end of A Farewell to Arms; it’s all of Faulkner, with his mortification of fatherhood and the dramatic responsibility fatherhood entails. It is a cost analysis that neglects any potential benefits.

But these are small criticisms of a large, beautiful, benevolent novel, a book that begs to be reread, a rambling picaresque of comic and tragic proportions. “I learned that there is one Suttree and one Suttree only,” our hero realizes, but this epiphany is set against a larger claim. Near the end of the novel, Suttree goes to check on an old ragman who he keeps a watchful eye on. He finds the man dead, his shack robbed, his body looted. Despairing over the spectacle’s abject lack of humanity, Suttree cries, “You have no right to represent people this way,” for “A man is all men. You have no right to your wretchedness.” Here, Suttree’s painful epiphany is real and true, an Emersonian insight coded in the darkest of Whitman’s language. If there is one Suttree and one Suttree only, he is still beholden to all men; to be anti-social or an outcast is not to be anti-human. Self-hood is ultimately conditional on others and otherness. To experience the other’s wretchedness is harrowing; to understand the other’s wretchedness and thus convert it to dignity is life-affirming and glorious. Suttree is a brilliant, bold, marvelous book. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note—Biblioklept originally published a version of this review on November 27, 2010].

Readers looking for redemptive story arcs or tales of heroism will likely be turned off by Child of God, and squeamish readers will probably not get past the first fifty pages. Those interested in McCarthy’s fiction will find more in common here with the visceral grit of

Readers looking for redemptive story arcs or tales of heroism will likely be turned off by Child of God, and squeamish readers will probably not get past the first fifty pages. Those interested in McCarthy’s fiction will find more in common here with the visceral grit of  In his

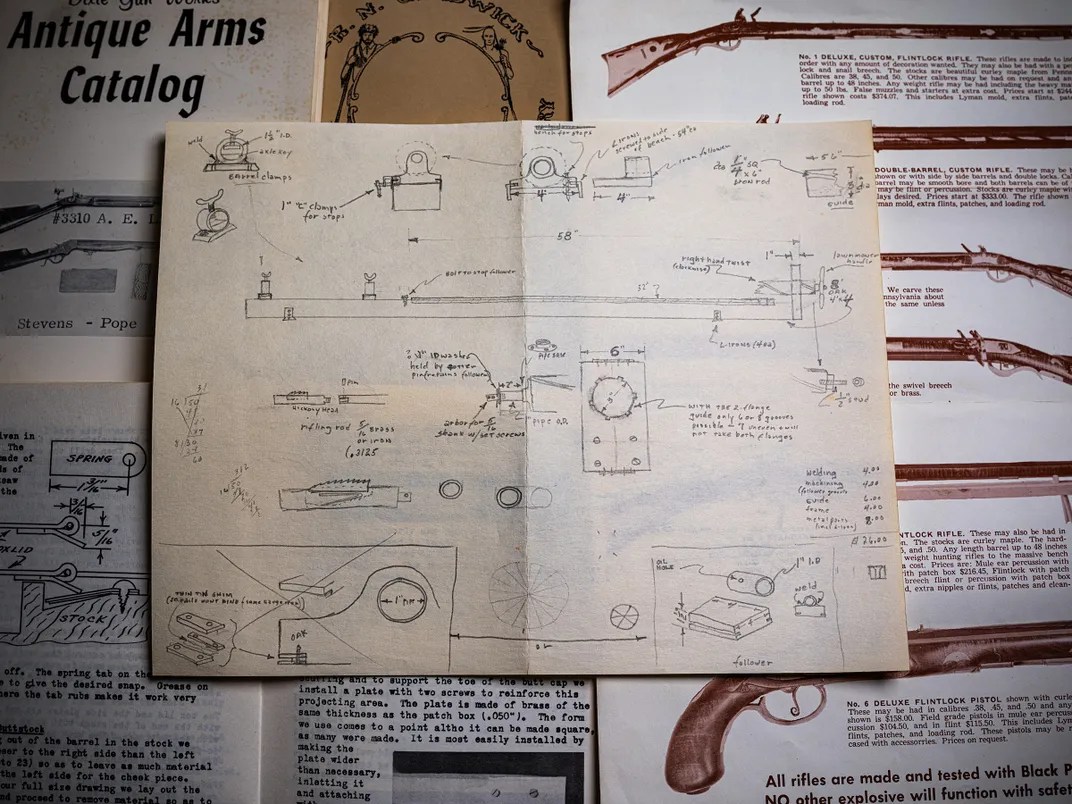

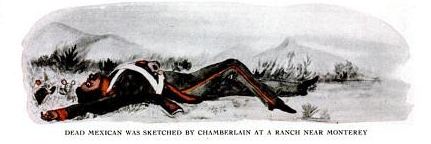

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s