INTERVIEWER

You’ve said that “one constantly takes prototypes from literature who may actually influence one’s conduct.” Could you give specific examples?

MURDOCH

Did I say that? Good heavens, I can’t remember the context. Of course, one feels affection for, or identifies with, certain fictional characters. My two favorites are Achilles and Mr. Knightley. This shows the difficulty of thinking of characters who might influence one. I could reflect upon characters in Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy; these writers particularly come to mind—wise moralistic writers who portray the complexity of morality and the difficulty of being good.

Plato remarks in The Republic that bad characters are volatile and interesting, whereas good characters are dull and always the same. This certainly indicates a literary problem. It is difficult in life to be good, and difficult in art to portray goodness. Perhaps we don’t know much about goodness. Attractive bad characters in fiction may corrupt people, who think, So that’s OK. Inspiration from good characters may be rarer and harder, yet Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov and the grandmother in Proust’s novel exist. I think one is influenced by the whole moral atmosphere of literary works, just as we are influenced by Shakespeare, a great exemplar for the novelist. In the most effortless manner he portrays moral dilemmas, good and evil, and the differences and the struggle between them. I think he is a deeply religious writer. He doesn’t portray religion directly in the plays, but it is certainly there, a sense of the spiritual, of goodness, of self-sacrifice, of reconciliation, and of forgiveness. I think that is the absolutely prime example of how we ought to tell a story—invent characters and convey something dramatic, which at the same time has deep spiritual significance.

Tag: Literature

Complaint to God (Alasdair Gray’s Lanark)

The more he worked the more the furious figure of God kept popping in and having to be removed: God driving out Adam and Eve for learning to tell right from wrong, God preferring meat to vegetables and making the first planter hate the first herdsman, God wiping the slate of the world clean with water and leaving only enough numbers to start multiplying again, God fouling up language to prevent the united nations reaching him at Babel, God telling a people to invade, exterminate and enslave for him, then letting other people do the same back. Disaster followed disaster to the horizon until Thaw wanted to block it with the hill and gibbet where God, sick to death of his own violent nature, tried to let divine mercy into the world by getting hung as the criminal he was. It was comical to think he achieved that by telling folk to love and not hurt each other. Thaw groaned aloud and said, “I don’t enjoy hounding you like this, but I refuse to gloss the facts. I admire most of your work. I don’t even resent the ice ages, even if they did make my ancestors carnivorous. I’m astonished by your way of leading fertility into disaster, then repairing the disaster with more fertility. If you were a busy dung beetle pushing the sun above the skyline, if you had the head of a hawk or the horns and legs of a goat I would understand and sympathize. If you headed a squabbling committee of Greek departmental chiefs I would sympathize. But your book claims you are a man, the one perfect man of whom we are imperfect copies. And then you have the bad taste to put yourself in it. Only the miracle of my genius stops me feeling depressed about this, and even so my brushes are clogged by theology, that bastard of the sciences. Let me remember that a painting, before it is anything else, is a surface on which colours are arranged in a certain order.

From Alasdair Gray’s novel Lanark.

Very few people who are supposedly interested in writing are interested in writing well (Flannery O’Connor)

But there is a wide spread curiosity about writers and how they work, and when a writer talks on this subject, there are always misconceptions and mental rubble for him to clear away before he can even begin to see what he wants to talk about. I am not, of course, as innocent as I look. I know well enough that very few people who are supposedly interested in writing are interested in writing well. They’re interested in publishing something, and if possible in making a “killing.” They are interested in seeing their names at the top of something printed, it matters not what. And they seem to feel that this can be accomplished by learning certain things about working habits and about markets and about what subjects are currently acceptable.

From “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” by Flannery O’Connor. Collected in Mystery and Manners.

RIP Walter Dean Myers

RIP Walter Dean Myers, 1937-2014

Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books? Where are the future white personnel managers going to get their ideas of people of color? Where are the future white loan officers and future white politicians going to get their knowledge of people of color? Where are black children going to get a sense of who they are and what they can be?

I taught for seven years in an inner city high school. I cannot overstate how important Myers’s books were to my students. His novel Monster—a classic—was one of the first books I wrote about on Biblioklept. I love the book, and I loved reading it with my students. Monster was an especially effective bridge to others by Myers–Slam!, Hoops, Bad Boy, The Beast—and one of my favorites, Fallen Angels—but I also saw it turn kids who hated reading into voracious readers. I read Myers myself as a young teen (his book Scorpions is especially good), but reading them again with my students revealed a depth and precision I hadn’t detected as a kid. Those books are all true, even the ones that are made up. RIP Walter Dean Myers.

A Riff on Stuff I Wish I’d Written About In the First Half of 2014

1. Leaving the Sea, Ben Marcus: A weird and (thankfully) uneven collection that begins with New Yorkerish stories of a post-Lish stripe (like darker than Lipsyte stuff) and unravels (thankfully) into sketches and thought experiments and outright bizarre blips. Abjection, abjection, abjection. The final story “The Moors” is a minor masterpiece.

2. Novels and stories, Donald Barthelme: A desire to write something big and long on Barthelme seems to get in the way of my writing anything about Barthelme. Something short then? Okay: Barthelme is all about sex. He posits sex as the solution (or at least consolation) for the problems of language, family, identity, etc.

3. Enormous Changes at the Last Minute and The Little Disturbances of Man by Grace Paley: I gorged on these precise, sad, funny stories, probably consuming too many at once (by the end of Little Disturbances I had the same stomach ache I got after eating too much of Barthelme’s Sixty Stories at once).

4. Concrete by Thomas Bernhard: Unlike the other novels I’ve read by Bernhard, Concrete seems to offer some kind of vision of moral capability, one which the narrator is unable to fully grasp, but which is nevertheless made available to the reader in the book’s final moments, accessible only through the novel’s layers of storytelling. Continue reading “A Riff on Stuff I Wish I’d Written About In the First Half of 2014”

Selections from One-Star Amazon Reviews of Joyce’s Ulysses

[Ed. note: The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To be clear, I think Ulysses is a marvelous, rewarding read. While one or two of the reviews are tongue-in-cheek, most one-star reviews of the book are from very, very angry readers who feel duped]

I can sum this book up in two words: “Ass Beating”.

What an awful book this is?

I bought this having been a huge fan of the cartoon series, but Mr Joyce has taken a winning formula and produced a prize turkey. After 20 pages not only had Ulysses failed to even board his spaceship, but I had no idea at all what on earth was going on. Verdict: Rubbish.

When an English/American writer try to explain his/her ideas about life(I mention ideas about meaning,purpose and philosophy of life)and when he/she try to do this with complicated ideas and long sentences(or like very short ones especially in this particular book);what his/her work become to is:A tremendous nonsense!!!

Thi’ got to be the worst, I- I – I mean the worst ever written book ever. Know why? ‘Cause he’ such a showoff, know what I MEAN? He’s ingenious I’ll giv’ ’em that, but ingenuity my friends tire and enervate. Get to the point and stick to it ‘s my motto.

This is one of those books that “smart” people like to “read.”

The grammar is so disjointed as to make it nearly impossible to read.

Ulysses is basically an unbridled attack on the very ideas of heroism, romantic love and sexual fulfillment, and objective literary expression.

What’s with all the foreign languages?

It has no real meaning.

It is a blasphemy that it ever was published.

Anyone who tells you they’ve read this so-called book all the way through is probably lying through their teeth.It is impossible to endure this torture.

A babbling, senseless tome upheld by “literary luminaries” who fear being cast into the tasteless bourgeois darkness for dissent? Yes, that’s the gist.

I discovered that the novel was not what I though it would be.

Joyce is an aesthetic bother of Marcel Duchamp (known for The Fountain, a urinal, now a museum piece) and John Cage (the composer of pieces for prepared piano, where the piano’s strings are mangled with trash.

Two positive things I can say about James Joyce is that he has a great sounding name and he gives wonderful titles to his works.

Ask yourself – are you going to enjoy a book that neccesitates your literature teacher lie next to you and explain its ‘sophistication’ to you ?

It’s the worst book which has ever been written.

Unless you really hate yourself, do not attempt to read this book.

The truth is this book stinks. For one thing it is vulgar, which, I hate to disappoint anyone, requires no talent at all. This is a talent any six year-old boy possesses.

The book is not so good, it is boring, it is a colection of words and a continuous experimentation of styles that, unhappily, do not mean anything to the meaning of the story; that is, the book’s language is snobbish and useless. Those who say that “love” such a writing are to be thought about as non-readers or as victims of a literary abnormality.

…the single most destructive piece of Literature ever written…

I’m all for challenging reads, but not for gibberish which academics persist in labeling erudition.

This book is extremely dull!!! My book club decided to read this book after one of the members visited the James Joyce tower in Ireland, which the author supposedly wrote part of the book in.

Ulysses is a failed novel because Joyce was a bad writer (shown by his other works).

In conclusion, Don’t read the book. Burn it hard. Do not let your children read the book—it will mutilate their brain cells.

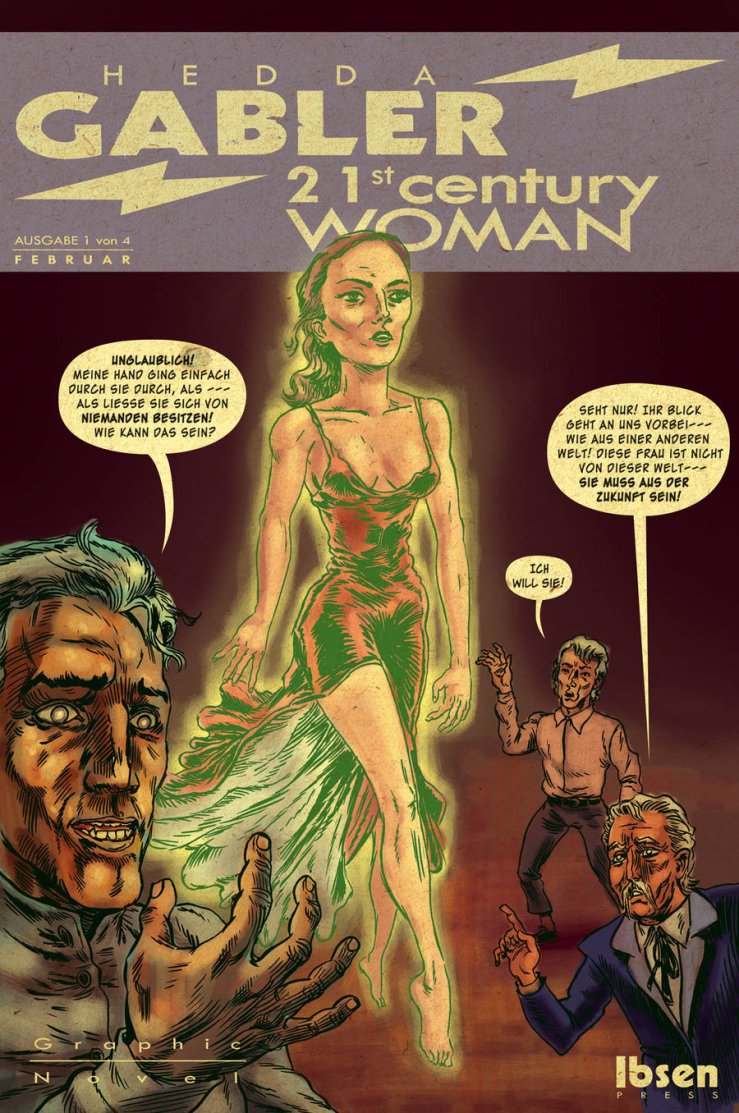

Hedda Gabler, 21st Century Woman — Ralph Niese

C’mon (Life in Hell)

Portrait of Walt Whitman — Thomas Wilmer Dewing

“Indian Camp” — Ernest Hemingway

“Indian Camp”

by

Ernest Hemingway

At the lake shore there was another rowboat drawn up. The two Indians stood waiting.

Nick and his father got in the stern of the boat and the Indians shoved it off and one of them got in to row. Uncle George sat in the stern of the camp rowboat. The young Indian shoved the camp boat off and got in to row Uncle George.

The two boats started off in the dark. Nick heard the oarlocks of the other boat quite a way ahead of them in the mist. The Indians rowed with quick choppy strokes. Nick lay back with his father’s arm around him. It was cold on the water. The Indian who was rowing them was working very hard, but the other boat moved further ahead in the mist all the time.

“Where are we going, Dad?” Nick asked.

“Over to the Indian camp. There is an Indian lady very sick.”

“Oh,” said Nick.

Across the bay they found the other boat beached. Uncle George was smoking a cigar in the dark. The young Indian pulled the boat way up on the beach. Uncle George gave both the Indians cigars. Continue reading ““Indian Camp” — Ernest Hemingway”

“Flavia and Her Artists” — Willa Cather

“Flavia and Her Artists”

by

Willa Cather

As the train neared Tarrytown, Imogen Willard began to wonder why she had consented to be one of Flavia’s house party at all. She had not felt enthusiastic about it since leaving the city, and was experiencing a prolonged ebb of purpose, a current of chilling indecision, under which she vainly sought for the motive which had induced her to accept Flavia’s invitation. Continue reading ““Flavia and Her Artists” — Willa Cather”

“As books multiply to an unmanageable excess, selection becomes more and more a necessity for readers” (Thomas De Quincey)

As books multiply to an unmanageable excess, selection becomes more and more a necessity for readers, and the power of selection more and more a desperate problem for the busy part of readers. The possibility of selecting wisely is becoming continually more hopeless as the necessity for selection is becoming continually more pressing. Exactly as the growing weight of books overlays and stifles the power of comparison, pari passu is the call for comparison the more clamorous; and thus arises a duty correspondingly more urgent of searching and revising until everything spurious has been weeded out from amongst the Flora of our highest literature, and until the waste of time for those who have so little at their command is reduced to a minimum. For, where the good cannot be read in its twentieth part, the more requisite it is that no part of the bad should steal an hour of the available time; and it is not to be endured that people without a minute to spare should be obliged first of all to read a book before they can ascertain whether in fact it is worth reading. The public cannot read by proxy as regards the good which it is to appropriate, but it can as regards the poison which it is to escape. And thus, as literature expands, becoming continually more of a household necessity, the duty resting upon critics (who are the vicarious readers for the public) becomes continually more urgent — of reviewing all works that may be supposed to have benefited too much or too indiscriminately by the superstition of a name. The praegustatores should have tasted of every cup, and reported its quality, before the public call for it; and, above all, they should have done this in all cases of the higher literature — that is, of literature properly so called.

Kierkegaard is an ugly hunchback loser

(And Yet Another) Moby-Dick (Book Acquired, 4.18.2014)

So I bought yet another copy of Moby-Dick, despite the many several editions already in our home.

I’d looked for an edition of the Barry Moser illustrated M-D for years—casually, in used book shops—but after a few (ahem) glasses of chardonnay, I bought one for next to nothing on eBay.

Moser’s etchings are superb, of course, and they most often illustrate the technical, scientific, or historical aspects of the novel. Great stuff.

With the assurance of a sleepwalker (William T. Vollmann)

Their slave-sister Guthrún, marriage-chained to Huns on the other side of the dark wood, sent Gunnar and Hogni a ring wound around with wolf’s hair to warn them not to come; but such devices cannot be guaranteed even in dreams. As the two brothers gazed across the hall-fire at the emissary who sat expectantly or ironically silent in the high-seat, Hogni murmured: Our way’d be fairly fanged, if we rode to claim the gifts he promises us! . . .—And then, raising golden mead-horns in the toasts which kingship requires, they accepted the Hunnish invitation. They could do nothing else, being trapped, as I said, in a fatal dream. While their vassals wept, they sleepwalked down the wooden hall, helmed themselves, mounted horses, and galloped through Myrkvith Forest to their foemen’s castle where Guthrún likewise wept to see them, crying: Betrayed!—Gunnar replied: Too late, sister . . .—for when dreams become nightmares it is ever too late.

When on Z-Day 1936 the Chancellor of Germany, a certain Adolf Hitler, orders twenty-five thousand soldiers across six bridges into the Rhineland Zone, he too fears the future. Unlike Gunnar, he appears pale. Frowning, he grips his left wrist in his right. He’s forsworn mead. He eats only fruits, vegetables and little Viennese cakes. Clenching his teeth, he strides anxiously to and fro. But slowly his voice deepens, becomes a snarling shout. He swallows. His voice sinks. In a monotone he announces: At this moment, German troops are on the march.

What will the English answer? Nothing, for it’s Saturday, when every lord sits on his country estate, counting money, drinking champagne with Jews. The French are more inclined than they to prove his banesmen . . .

Here comes an ultimatum! His head twitches like a gun recoiling on its carriage. He grips the limp forelock which perpetually falls across his face. But then the English tell the French: The Germans, after all, are only going into their own back garden.—By then it’s too late, too late.

I know what I should have done, if I’d been the French, laughs Hitler. I should have struck! And I should not have allowed a single German soldier to cross the Rhine!

To his vassals and henchmen in Munich he chants: I go the way that Providence dictates, with the assurance of a sleepwalker.—They applaud him. The white-armed Hunnish maidens scream with joy.

From William Vollmann’s Europe Central.

For the past 100 pages or so, Vollmann has referred to Hitler as the sleepwalker (I’m almost positive that the word Hitler hasn’t been used in the text up until now), and while context has made it clear that this sleepwalker is Hitler, the source of the moniker is only clarified at this point.

How can love be self-ironic? (William T. Vollmann)

I promise you that from the first time she took his hand—the very first time!—he actually believed; she was ready, lonely, beautiful; she wanted someone to love with all her heart and he was the man; she longed to take care of him, knowing even better than he how much he needed to be taken care of—he still couldn’t knot his necktie by himself, and, well, you know. He believed, because an artist must believe as easily and deeply as a child cries. What’s creation but self-enacted belief? —Now for a cautionary note from E. Mravinsky: Shostakovich’s music is self-ironic, which to me implies insincerity. This masquerade imparts the spurious impression that Shostakovich is being emotional. In reality, his music conceals extremely deep lyric feelings which are carefully protected from the outside world. In other words, is Shostakovich emotional or not? Feelings conceal—feelings! Could it be that this languishing longing I hear in Opus 40 actually masks something else? But didn’t he promise Elena that she was the one for him? And how can love be self-ironic? All right, I do remember the rocking-horse sequence, but isn’t that self-mockery simply self-abnegation, the old lover’s trick? Elena believes in me, I know she does! How ticklishly wonderful! Even Glikman can see it, although perhaps I shouldn’t have told Glikman, because . . . What can love be if not faith? We look into each other’s faces and believe : Here’s the one for me! Lyalya, never forget this, no matter how long you live and whatever happens between us: You will always be the one for me. And in my life I’ll prove it. You’ll see. Sollertinsky claims that Elena’s simply lonely. What if Elena’s simply twenty? Well, I’m lonely, too. Oh, this Moscow-Baku train is so boring. I can’t forgive myself for not kidnapping my golden Elenochka and bringing her to Baku with me. Or does she, how shall I put this, want too much from destiny? My God, destiny is such a ridiculous word. I’ll try not to be too, I mean, why not? It’s still early in my life. That nightmare of the whirling red spot won’t stop me! I could start over with Elena and . . . She loves me. Ninusha loves me, but Elena, oh, my God, she stares at me with hope and longing; her love remains unimpaired, like a child’s. I love children. I want to be a father. I’ll tell Nina it’s because she can’t have children. That won’t hurt her as much as, you know. Actually, it’s true, because Nina . . . Maybe I can inform her by letter, so I don’t have to . . . Ashkenazi will do that for me if I beg him. He’s very kind, very kind. Then it will be over! As soon as I’m back in my Lyalka’s arms I’ll have the strength to resolve everything. If I could only protect that love of hers from ever falling down and skinning its knee, much less from growing up, growing wise and bitter! Then when she’s old she’ll still look at me like that; I’ll still be the one for her.

From William T. Vollmann’s big fat historical novel Europe Central, which is so big and fat that I think a comprehensive review of it will be just maybe beyond me by the time I get to the end of it, so maybe some citation, a bit of riffing, yes?

The novel recounts (a version) of the Eastern front of WWII. Polyglossic, discontinuous, musical, mythic, often discordant, Vollmann shifts through a series of narrators, his turns oblique, jarring. And while Vollmann includes political and military leaders, his analsyis/diagnosis focuses on artists, musicians, and writers. The above passage—which struck me especially for its discussion of the feeling of feeling, the aesthetics of feeling—this passage offers a neat encapsulation of Vollmann’s narrative digressions.

The “I” at the beginning of the citation is one of the “Shostakovich” sections narrators. Although unnamed (as of yet), he seems to be a high-ranking officer in Stalin’s secret police. At times though, this narrator—all of the narrators!—seem to merge consciousness with Vollmann, the novel’s architect, who interposes his own research and readings (or are they the narrators?). We see this in the dash introducing some lines from the conductor Evegny Mravinsky—key lines that I find fascinating—which Vollmann (or Vollmann’s narrator) uses to critique/question the relationship between art, emotion, intention, and authenticity (current subjects of deep fascination for me). Then—then!—without warning, Vollmann enters the consciousness of another “I,” Shostakovich himself, whose elliptical thoughts, muddied and warbling, illustrate, illuminate, and complicate Mravinsky’s critique.

Feelings conceal—feelings!—yes, yes, yes I think so: Here Vollmann (through several layers of complicating narrators, which lets just set aside for a second, or perhaps altogether, at least for now)—here Vollmann offers a fascinating description followed by its problem: If earnest expression can be couched in irony—if we use feelings to hide other feelings in art (etc.)—then what does that mean for love, which I think Vollmann (here, elsewhere) believes to be A Big Important Thing? Is a self-ironic love possible? Likely even?

I’m tempted here to deflect, move to another piece of art, like say, It’s A Wonderful Life, a film that I understand anew every year, a film I found baffling, frightening as a child; a film that bored me as teen; a film that I resented as a young man; a film that I appreciated with a winking ironic cheer a few years later—and then, now, or nowish, as an adult, a film I feel I understand, that its sentiment, raw, affects me more deeply than ever. (I was right as a child to be baffled and frightened). (What if anything self-ironic love?).

So I deflected. And am ranting, trying to set out a few thoughts for Something Bigger—something on Authenticity and Inauthenticity, The Con-Artist vs. The Poseur, the Aesthetics of Feeling the Feeling, of Anesthetizing the Feeling (of Feeling the Feeling). Look at me, I capitalized some of my words. Sorry.

“I stole a book” (Clarice Lispector)

The moment her aunt went to pay for her purchases, Joana removed the book and slipped it furtively between the others she was carrying under her arm. Her aunt turned pale.

Once in the street, the woman chose her words carefully:

— Joana.. . Joana, I saw you…

Joana gave her a quick glance. She remained silent.

— But you have nothing to say for yourself? — her aunt could no longer restrain herself, her voice tearful. — Dear God, what is to become of you?

— There’s no need to fuss, Auntie.

— But you’re still a child… Do you realize what you’ve done?

— I know…

— Do you know… do you know what it’s called… ?

— I stole a book, isn’t that what you’re trying to say?

— God help me! I don’t know what I’m going to do, you even have the nerve to own up!

— You forced me to own up.

— Do you think that you can… that you can just go around stealing?

— Well… perhaps not.

— Why do you do it then… ?

— Because I want to.

— You what?

— her aunt exploded.

— That’s right, I stole because I wanted to. I only steal when I feel like it. I’m not doing any harm.

— God help me! So, stealing does no harm, Joana.

— Only if you steal and are frightened. It doesn’t make me feel either happy or sad.

The woman looked at her in despair.

— Look child, you’re growing up, it won’t be long before you’re a young lady… Very soon now you will be wearing your clothes longer… I beg of you: promise me that you won’t do it again, promise me, think of your poor father who is no longer with us.

Joana looked at her inquisitively:

— But I’m telling you I can do what I like, that…

A biblioklept episode from Clarice Lispector’s novel Near to the Wild Heart.