Is there anything worse than a beloved book sporting a movie tie-in cover? (Okay. Maybe Oprah’s blazon is worse).

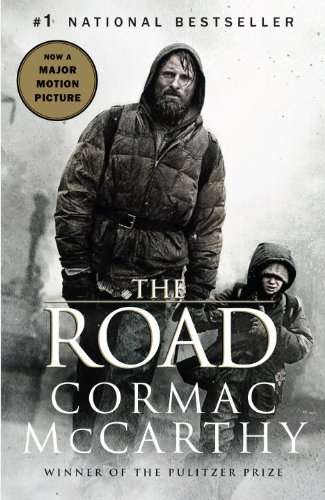

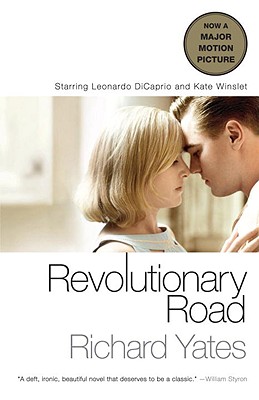

It’s not like the original cover was that great, or that the movie was that bad, but the whole enterprise of slapping grim Viggo Mortensen all over Cormac McCarthy’s The Road doesn’t seem to make much sense (maybe they didn’t realize that the film was going to flop and hoped that it would re-energize book sales). It seems like a slight to any reader new to the book. The austere original cover omits all imagery and thus places McCarthy’s language front and center. Movie tie-ins tend to plaster major Hollywood actors all over the cover, making it difficult for readers to re-frame or re-image the characters that those actors are playing–it’s an egregious intrusion between the writer’s text and the reader. It disrupts visualization. It also tends to look tacky, even when it’s “classy.” Take for example this cover for Richard Yates’s novel Revolutionary Road —

I’ve never read the novel, although I’ve often heard it referred to as an under-read or “lost” classic (the film promos made it look dreadfully boring, but there is probably nothing more unfair than judging a book by its movie). Spying its spine, I picked the book up the other day at the bookstore but could not even flick through it. All I could see was Leo and Kate. Then there’s that Big Gold Sticker procliaimng the work is “Now A Major Motion Picture.” The statement, emboldened in all-caps seems set apart in its little golden sphere, but oddly enough there’s a clause that must logically follow it — “Starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet.” The aesthetic logic of the cover though seems to suggest, however ludicrous, that DiCaprio and Winslet actually star in the book. Were I to attempt to read this edition of the book my poor imagination, weakened by years of watery domestic beer and bad television, would not be able to surmount the challenge posed by the cover. Each time I dipped into its pages, surely Yates’s prose, no matter how descriptive or visceral or imagistic, must fall to the glamor of Leo and Kate.

I’ve never read the novel, although I’ve often heard it referred to as an under-read or “lost” classic (the film promos made it look dreadfully boring, but there is probably nothing more unfair than judging a book by its movie). Spying its spine, I picked the book up the other day at the bookstore but could not even flick through it. All I could see was Leo and Kate. Then there’s that Big Gold Sticker procliaimng the work is “Now A Major Motion Picture.” The statement, emboldened in all-caps seems set apart in its little golden sphere, but oddly enough there’s a clause that must logically follow it — “Starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet.” The aesthetic logic of the cover though seems to suggest, however ludicrous, that DiCaprio and Winslet actually star in the book. Were I to attempt to read this edition of the book my poor imagination, weakened by years of watery domestic beer and bad television, would not be able to surmount the challenge posed by the cover. Each time I dipped into its pages, surely Yates’s prose, no matter how descriptive or visceral or imagistic, must fall to the glamor of Leo and Kate.

Maybe it’s just me though–I can remember having this problem even in childhood, absolutely hating to read any book that proffered a photograph of a person, especially an actor, masquerading as a character that my imagination was supposed to bring to life. For some reason paintings and other stylized images didn’t –and don’t — offend me in this way.

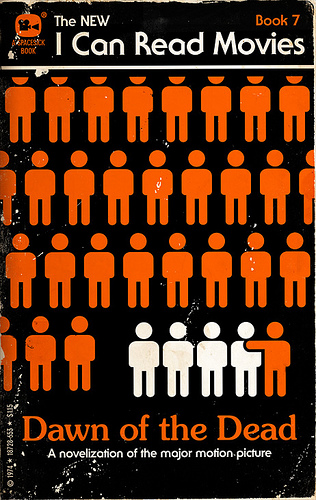

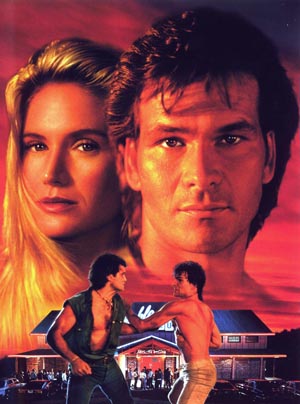

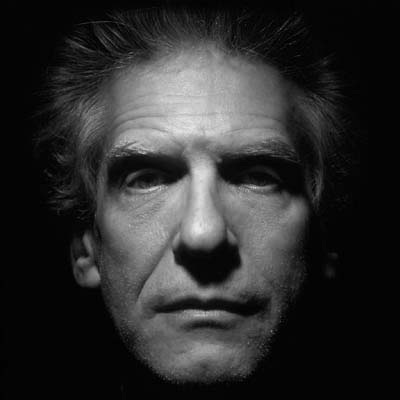

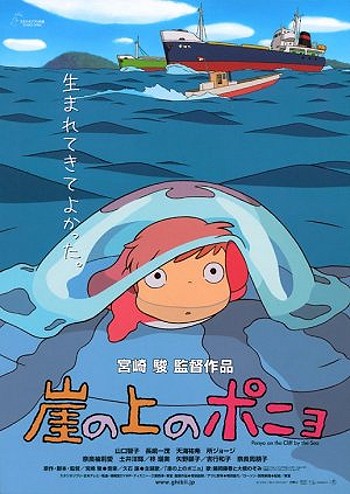

I suppose that movie tie-in covers help sell books and, ultimately, that’s a good thing, but I can’t think of a single one I’ve ever seen that’s aesthetically pleasing. I’m reminded now of Spacesick’s “I Can Read Movies” Series, which achieves the opposite, turning movies into witty, wonderful book covers. Observe: