We were about an hour north of the border, driving a rented car from Quebec City to a hiker hostel our friends own in Maine, when I got a text from my uncle: “It seems your favorite author has died…” (The ellipses were part of his text.)

At first, I thought he meant Thomas Pynchon, who is 86, which is pretty old. I opened Twitter and realized he meant Cormac McCarthy, who is also my favorite author, who died at the age of 89 about a week ago.

It may be unseemly to bring up another author, Pynchon, in an ostensible eulogy for McCarthy (to be clear, this is not a eulogy, this is a riff)—but I found my reactions to the non-news of Pynchon’s non-death and the true-news of McCarthy’s true-death revealing, insomuch as my reactions revealed how I thought about these two writers’ latest and last works. Simply put, I felt a sharp, ugly pang at the thought that there might not be one last Pynchon novel in the author’s lifetime, one last big, baggy, flawed, majestic synthesis of the artist’s oeuvre to capstone the grand career.

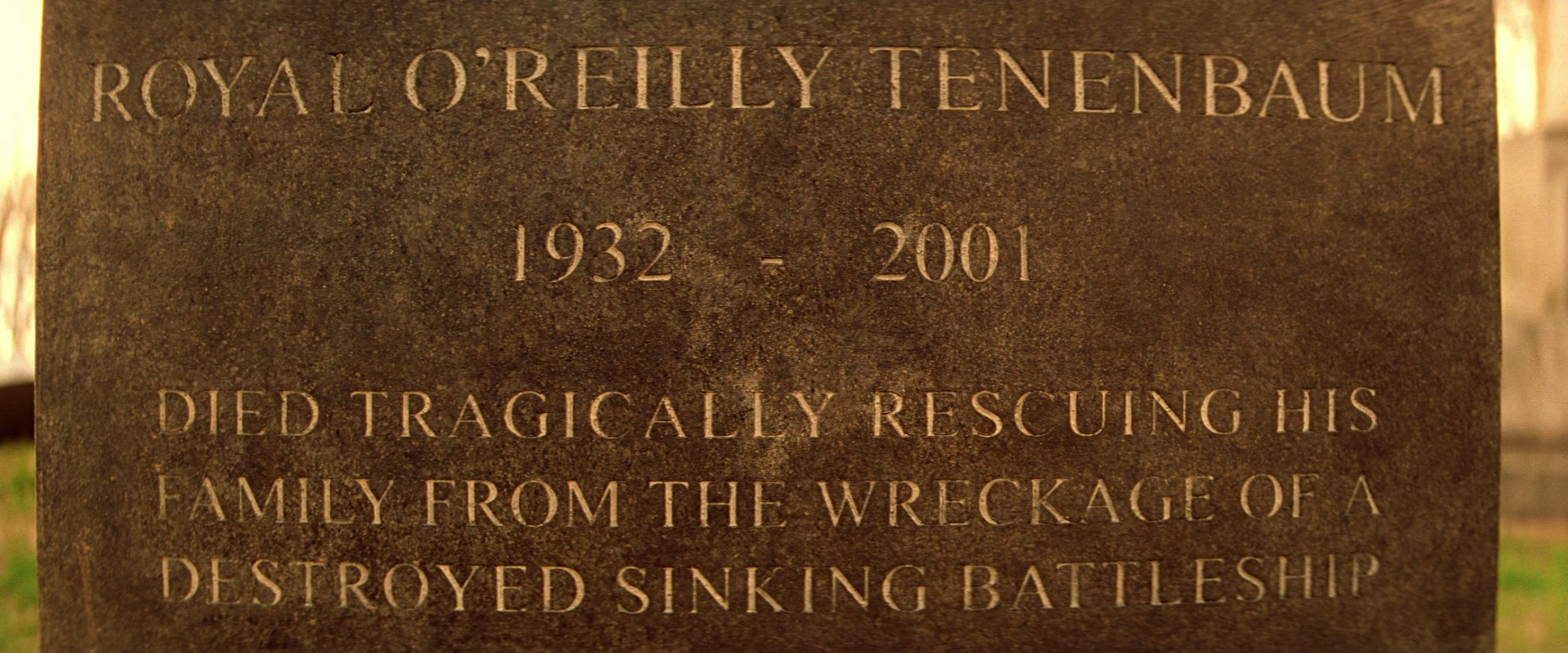

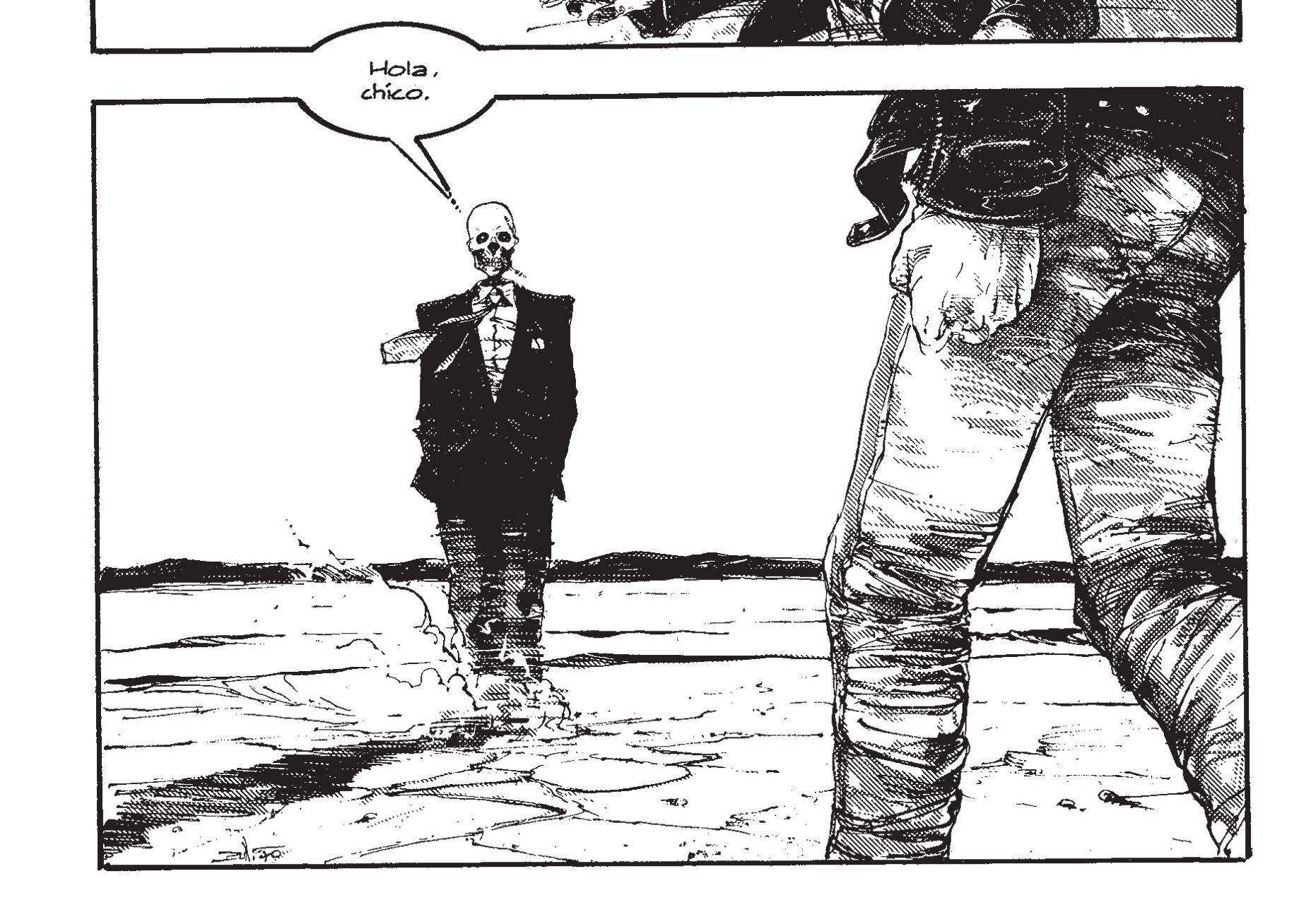

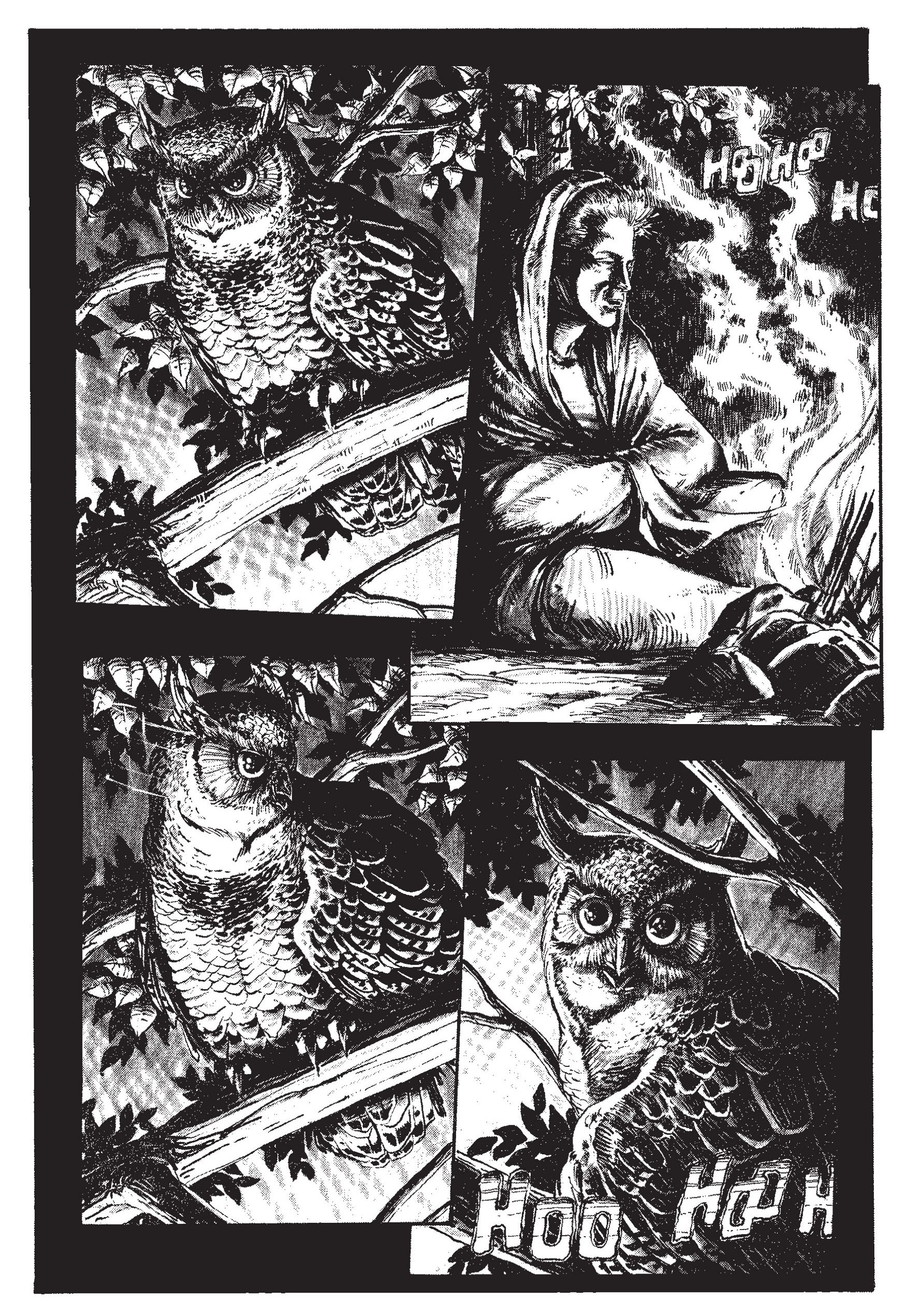

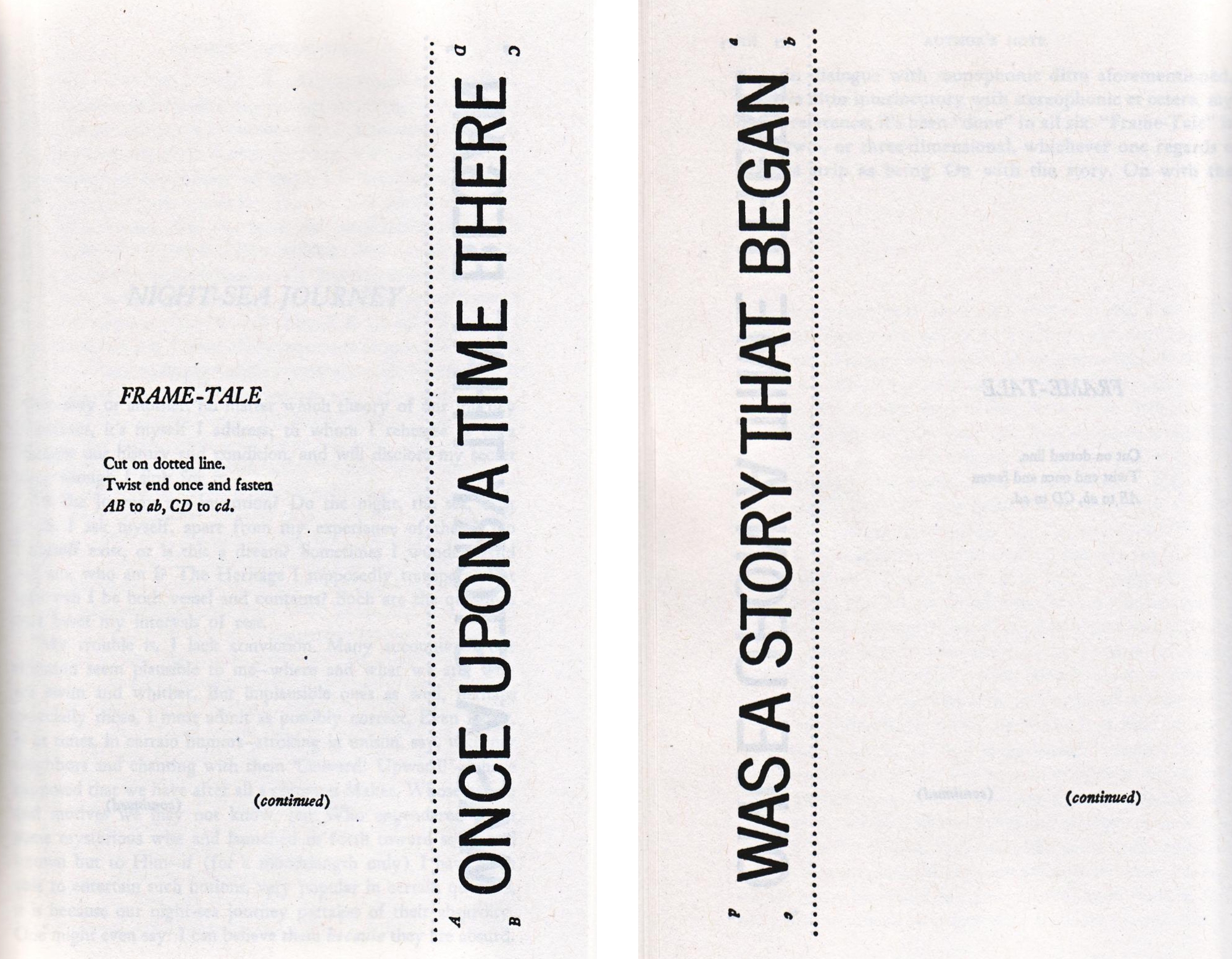

Cormac McCarthy published his big, baggy, flawed, majestic capstone last year and titled it The Passenger. It confused and irritated many reviewers and readers, who were likely expecting something other than a sprawling and elliptical summation of the philosophical and aesthetic preoccupations of McCarthy’s previous work. (I made an indirect argument for The Passenger as the elliptical summation of the philosophical and aesthetic preoccupations of McCarthy’s previous work in a series of riffs.) The subsequent release of Stella Maris, a short, spare novella composed entirely in dialogue further befuddled many readers. Neither sequel nor coda, Stella Maris is a cold satellite orbiting The Passenger’s strange sun. Or maybe Stella Maris is The Passenger’s incestuous sibling; the very nature of its publication as a separate text deliberately invites us to read the novels intertextually. And then to read the sibling novels intertextually with/against the McCarthy family of novels.

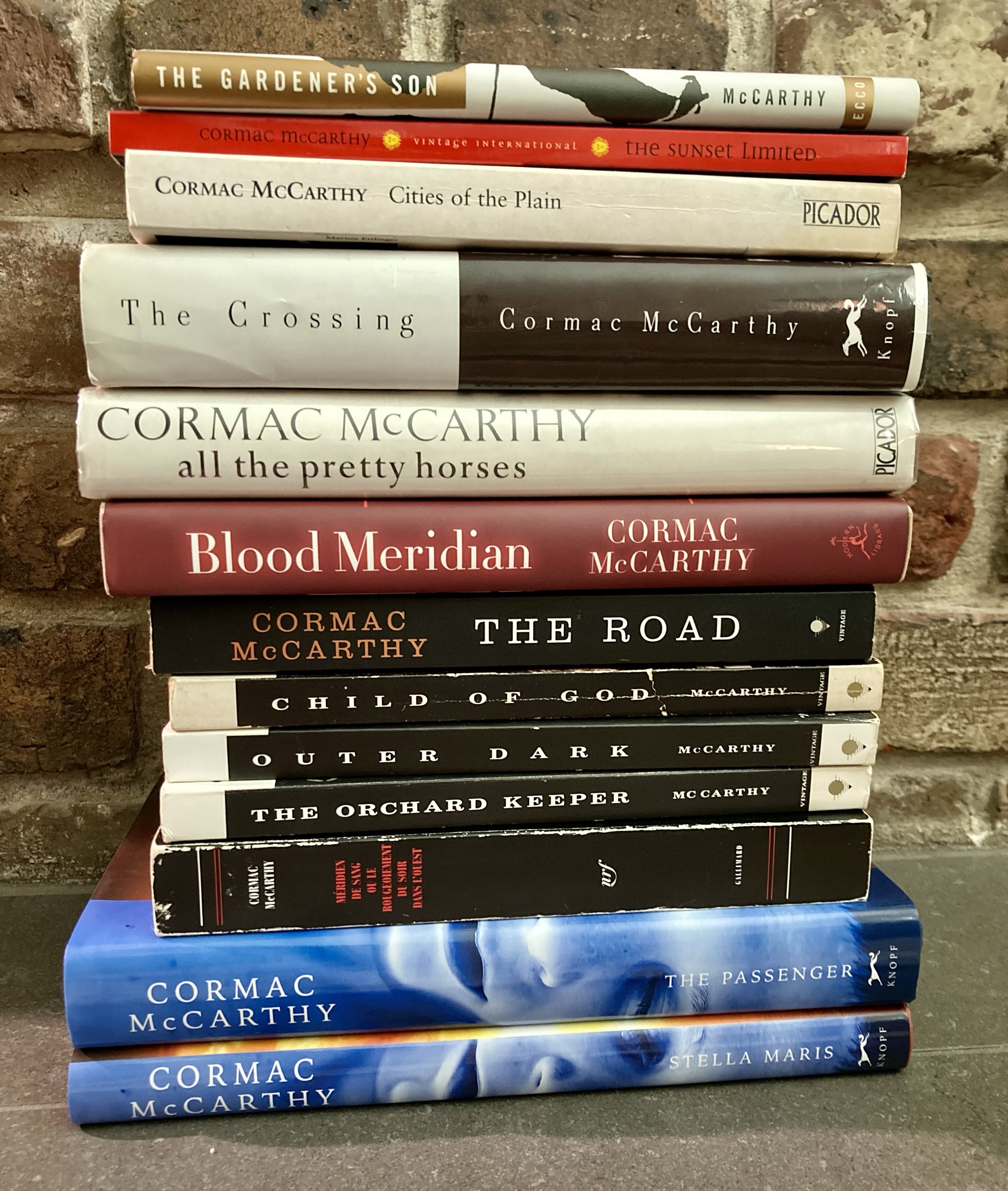

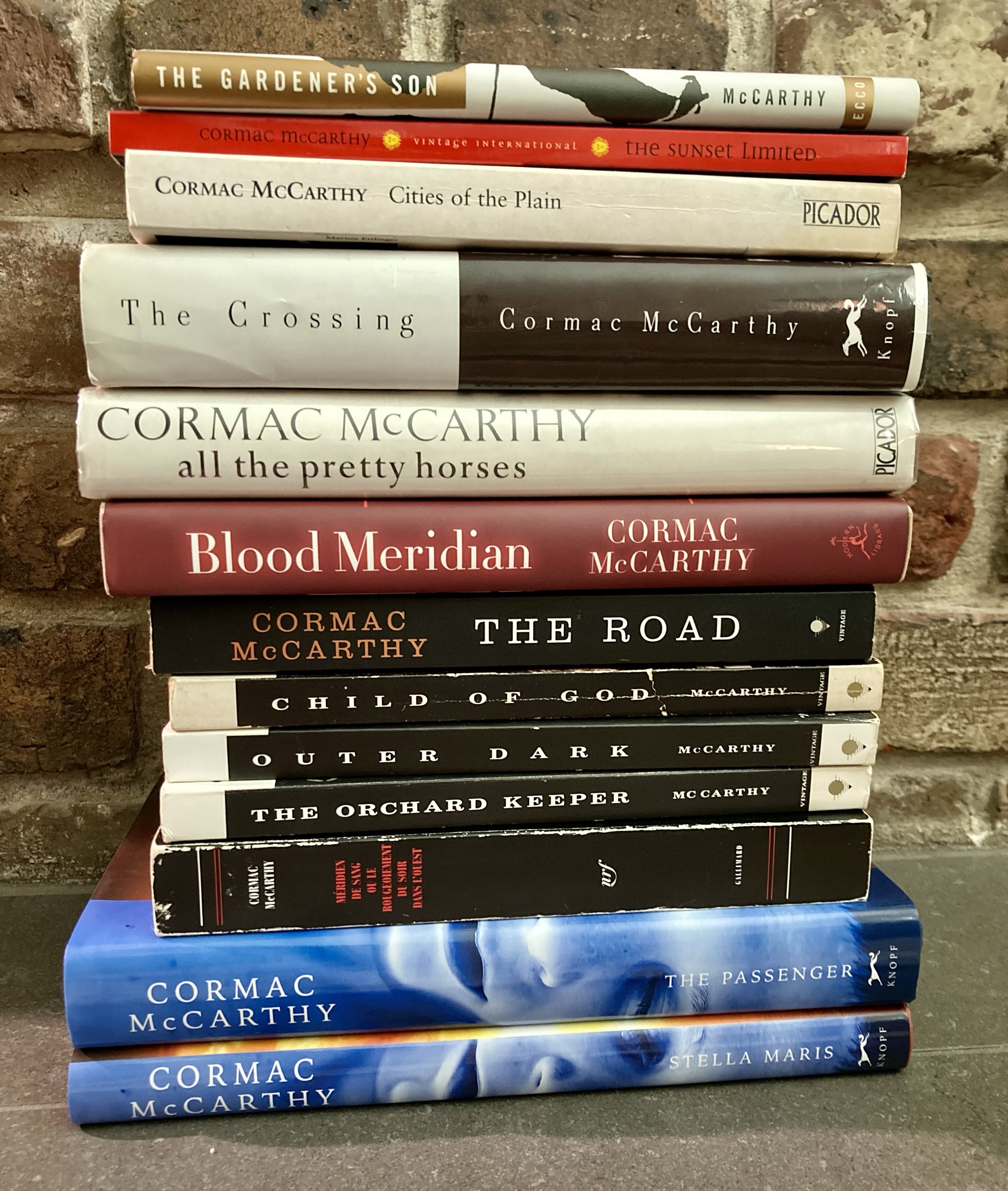

A proper eulogy (which this riff is not) would remark at some length on the McCarthy family of novels. Such a eulogy might demarcate the novels by both time and location, perhaps separating the early Southern novels (The Orchard Keeper, 1965; Outer Dark, 1968; Child of God, 1973; Suttree, 1978) from the later Westerns (1985’s Blood Meridian up through No Country for Old Men, 2005). Such a eulogy might also point to the commercial success and film adaptations of All the Pretty Horses (1992), No Country for Old Men, and 2006’s The Road. There’s even a segue there, I suppose, to mention McCarthy’s own efforts at screenwriting (The Gardener’s Son, 1976; The Counselor, 2013) and stage writing (The Stonemason, 1995; The Sunset Limited, 2006). Another segue presents itself: one might suggest that these screen and stage efforts need not be situated in McCarthy’s oeuvre. The eulogist might then attend himself to sorting McCarthy’s work into tiers: Blood Meridian and Suttree; The Crossing and The Passenger; everything else. But this riff is not a eulogy.

A eulogy, which this riff is not, should ideally contain a kernel of grief. Like most of his readers, I did not know Cormac McCarthy except through his work, and I feel gratitude for that work—for Blood Meridian and Suttree in particular, but also for The Passenger, which, as I’ve stated above, serves as a perfectly imperfect final marker for a fantastic and rightfully-lauded career. There’s no grief then; McCarthy wrote everything he could possibly write.

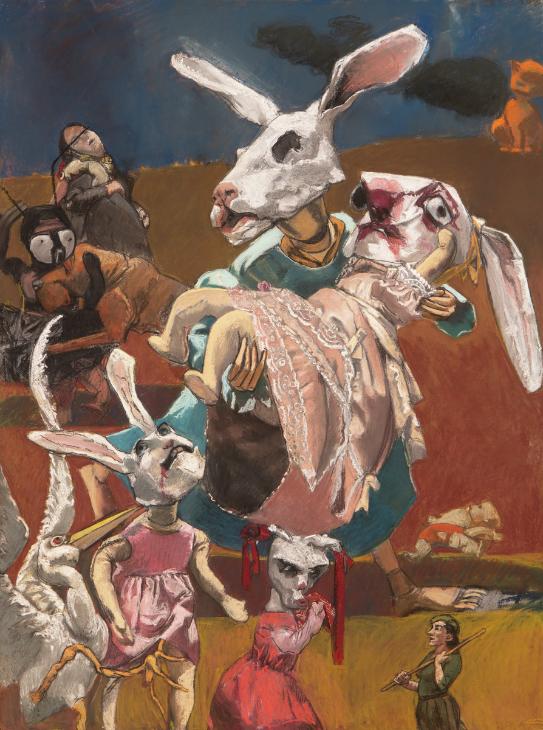

He was still writing at the time of his death, of course. Director John Hillcoat revealed just a few weeks ago that he was co-writing the screenplay for a Blood Meridan adaptation with McCarthy. Hillcoat, who adapted The Road into a 2009 film, did know McCarthy, and was working with him, again, and thus might feel a grief personal and professional, a grief and love that licensed him to author a eulogy for his friend, which he did here. I have no such license.

As my wife finished the drive from Quebec to Maine, I scrolled through Twitter, where readers and authors shared their thoughts on McCarthy’s passing. We soon arrived at our friends’ hostel, a large, comfortable old house not too far from the Appalachian Trail’s northern terminus. Years ago, one of these friends became infected with Blood Meridian, obsessed with its bombastic language. I spied his worn copy on the shelf, next to the copy of Suttree I had given him, which he still hasn’t finished. I vaguely recall toasting “Cormac” over some too-strong IPAs that night.

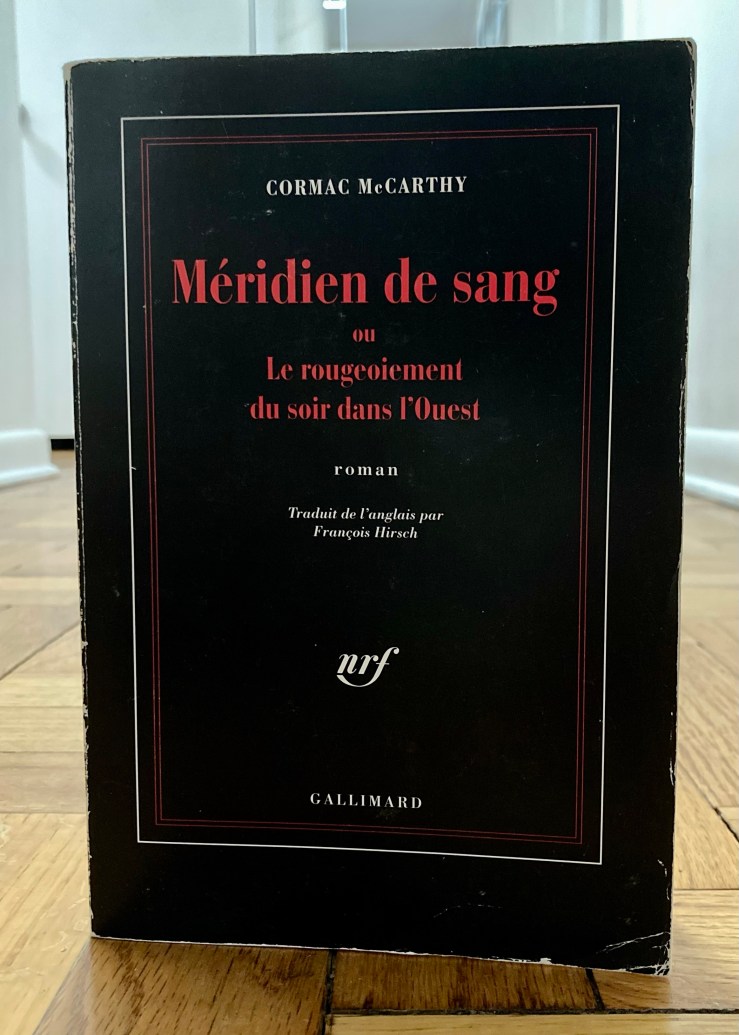

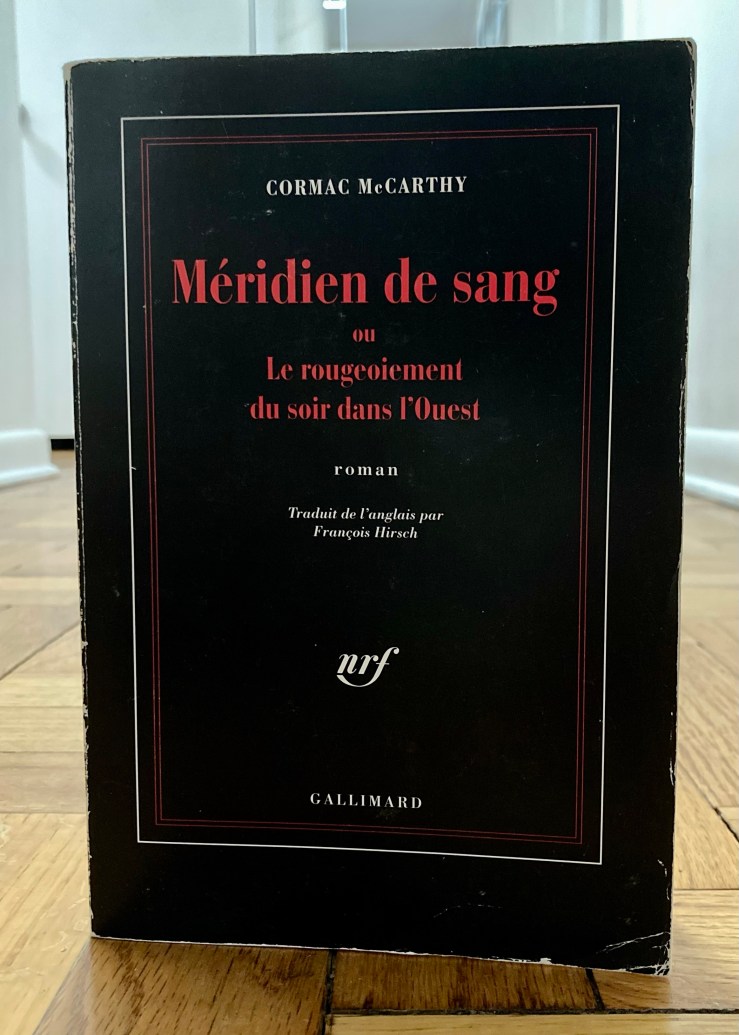

We drove back to Quebec City the following afternoon. (It is nice to visit one’s friends and see the hiker hostel they operate, but a hiker hostel is not a comfortable place for a family who is not hiking.) A day or two later we strolled Rue Saint-Jean outside of the Old City, where I visited four used bookstores. I can’t really read French, but I enjoy looking at book covers and simply looking at what’s in stock at a particular place. I ended up buying a used copy of François Hirsch’s French translation of Blood Meridian that I found for about eight U.S. dollars. I read the “legion of horribles” passage in Hirsch’s translation, and while my French vocabulary is awful, I know the book well enough to have enjoyed the experience. “Oh mon Dieu, dit le sergent” even made me crack up.

I was far from Florida and my home and my laptop in my home, so I did not write any riff on the death of Cormac McCarthy. I recycled old posts I’d written, reading and editing them from my phone, finding some of my early reviews pretty callow. My 2008 first-read review of Blood Meridian is particularly bad; the book clearly overwhelmed me. I’ve read it many, many times since then. The “review” I wrote of No Country back in 2007 is so bad I won’t even link to it. Like most great writers, McCarthy’s work is best reread, not read.

And I reread so much of his work this year. The Passenger left me wanting more McCarthy–not in an unsatisfied way, but rather to confirm my intimations about its status as a career capstone. I reread All the Pretty Horses in the lull before Stella Maris arrived. I went on to reread The Crossing (much, much stronger than I had remembered), Cities of the Plain (weaker than I had remembered), The Road (about exactly as I remembered), Child of God (ditto), and The Orchard Keeper (as funny as I had remembered but also much sadder than I had remembered).

This riff has been too long and too self-indulgent; it was not (as I promised it would not be) a eulogy for the great dead writer, but rather blather on my end—a need to get something out of my own system. If I were younger and more full of foolish energy, I’d probably take the time to rebut McCarthy’s detractors, critics who take to task both his baroque style and dark themes. The truth is I don’t care—I’ve got the books, I’ve read them and reread them, and I know what’s there and how it rewards my attention.

I’ll end simply by inviting anyone interested in McCarthy’s work to read him. And then I’ll really end, here, now, end this riff, with a Thank you to the void.