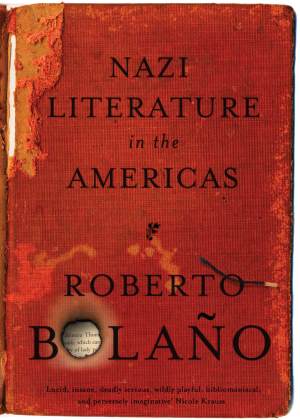

I hate reviews that hem and haw too much over context, but I feel that a proper review of Roberto Bolaño: The Last Interview has to begin with some background information. But because I love you, gentle reader, as much as I hate context-driven reviews, here’s the quick version: if you, like me, have found yourself compelled to read everything by Bolaño that you could get your hands on in the the past year or two, then you should buy and read The Last Interview because you will enjoy it. Now for the context:

When Bolaño died at age 50 in 2003, he was only just rising to prominence as a fiction writer, with most of that prominence still restricted to the Spanish-speaking world. Bolaño’s tremendous success has been mostly posthumous and there really aren’t that many interviews with the man. Roberto Bolaño: The Last Interview collects four of them, scattered between 1999 and 2003. Up until now, not all of these interviews were available in English (unless you took the time to put them in a translator program like Babel Fish. Which I did. Quick note: Sybil Perez’s translations here are better than the syntax soup I got via Babel Fish). The book gets its name from Bolaño’s last interview, conducted by Mónica Maristain in a 2003 issue of the Mexican edition of Playboy; that longish interview makes up the bulk of this book. There’s also an essay entitled “Alone Among the Ghosts” by Marcela Valdes, previously published in a 2008 issue of The Nation.

“Alone Among the Ghosts” works as a sort of preface for the interviews, providing a brief overview of Bolaño’s oeuvre and shedding light on his working methods. In particular, “Ghosts” details how Bolaño researched the gruesome crimes at the heart of 2666. The interviews that follow range in tone from flighty (Maristain’s Playboy interview) to intimate (Carmen Boullosa’s inteview in Bomb), but all share one common trait: each interviewer attempts to get Roberto Bolaño to name his place in the canons of Spanish and world literature. The interviews, much like Bolaño’s at-times-esoteric (at least to this English speaker) novel The Savage Detectives, are chock full of literary references to Spanish-language writers, poets, and critics, and each interviewer seems to delight in pushing Bolaño into saying something provocative about other writers. Tom McCartan’s annotations, located in the margins of this extra-wide book, help to enlighten those of us who are unfamiliar with the greater (and lesser) fights and scandals of Latin American literature. In his books, Bolaño often satirized the petty in-fighting between various literary groups, at the same time revealing the paradoxically serious nature of these conflicts. One of the best examples comes from The Savage Detectives–Bolaño’s stand-in Arturo Belano fights a duel with a critic on a beach in an episode that’s both hilarious, pathetic, and slightly horrifying. In the interviews, you get the sense that Bolaño is both provoking literary battles and, at the same time, downplaying them. He’s serious about his aesthetic values but knows that most of the world is not–he knows that most of the world is concerned with more immediate and perhaps weightier concerns like family, sex, and death. It’s on these subjects that Bolaño the interviewee is more poignant and candid–and fun.

There is a sense of creation in these interviews, of Bolaño creating a public self through his answers. It’s at these times that you can almost sense Bolaño writing. On the one hand, it’s a treat to see his voice so fresh and immediate, but on the other hand, in the context of an interview, it lends credence to the notion that he’s resisting presenting an authentic “self” (please put aside all postmodern arguments about authenticity, identity, and textuality for a few moments). Consider his response to his “enemies”:

Every time I read that someone has spoken badly of me I begin to cry, I drag myself across the floor, I scratch myself, I stop writing indefinitely, I lose my appetite, I smoke less, I engage in sport, I go for walks on the edge of the sea, which by the way is less than 30 meters from my house, and I ask the seagulls, whose ancestors ate the fish who ate Ulysses: Why me? Why? I’ve done you no harm.

A lovely passage. Apparent sincerity gives way to hyperbole gives way to healthy habits gives way to literary allusion–and perhaps hints of bathos. I get the sense that Bolaño is pulling a collective leg here, yet, there must be a kernel of truth to the notion that his critics affect him. In any case, the response, in its compelling rhythm and pathetic humor, might fit neatly into one of Bolaño’s books, where the author has often blurred the lines between fact and fiction.

These interviews will no doubt be pored over as “Bolaño Studies” hits academia hard, and would-be Bolaño scholars try to parse out their own narratives against the myriad gaps in Bolaño’s record. For more on the many inconsistencies in Bolaño’s life, check out this story from the The New York Times, which interviews family, friends, and literary associates to tease truth out of some of Bolaño’s grander embellishments. Of course, Bolaño was not solely responsible for all exaggerations. From the interview first published in Turia:

“It’s the typical Latin American tango. In the first book edited for me in Germany, they give me one month in prison; in the second book–seeing that the first one hadn’t sold so well–they raise it to three months; in the third book I’m up to four months, in the fourth it’s five. The way it’s going, I should still be a prisoner now.”

The New York Times article questions whether Bolaño even spent the eight days in a Chilean prison that he claims he did. Whether or not that ruins the authenticity of Bolaño’s short story “Dance Card,” collected in Last Evenings on Earth, is totally up to you of course, dear reader, but I think that self-invention has always been the privilege of the writer. If the interviews collected in The Last Interview reveal a myth-maker creating a self, they are also transparent and humorous in these creations. Highly recommended.

Roberto Bolaño: The Last Interview is now available from Melville House. For a detailed account of the authors mentioned in the interviews, read Tom McCartan’s fantastic series “What Bolaño Read.”

On that book specifically (and Bolaño’s work in general)–

On that book specifically (and Bolaño’s work in general)–