I liked pretty much all of the assigned reading in high school (okay, I hated every page of Tess of the D’Ubervilles). Some of the books I left behind, metaphorically at least (Lord of the Flies, The Catcher in the Rye), and some books bewildered me, but I returned to them later, perhaps better equipped (Billy Budd; Leaves of Grass). No book stuck with me quite as much as Candide, Voltaire’s scathing satire of the Enlightenment.

I remember being unenthusiastic when my 10th grade English teacher assigned the book—it was the cover, I suppose (I stole the book and still have it), but the novel quickly absorbed all of my attention. I devoured it. It was (is) surreal and harsh and violent and funny, a prolonged attack on all of the bullshit that my 15 year old self seemed to perceive everywhere: baseless optimism, can-do spirit, and the guiding thesis that “all is for the best.” The novel gelled immediately with the Kurt Vonnegut books I was gobbling up, seemed to antecede the Beat lit I was flirting with. And while the tone of the book certainly held my attention, its structure, pacing, and plot enthralled me. I’d never read a book so willing to kill off major characters (repeatedly), to upset and displace its characters, to shift their fortunes so erratically and drastically. Not only did Voltaire repeatedly shake up the fortunes of Candide and his not-so-merry band—Pangloss, the ignorant philosopher; Cunegonde, Candide’s love interest and raison d’etre and her maid the Old Woman; Candide’s valet Cacambo; Martin, his cynical adviser—but the author seemed to play by Marvel Comics rules, bringing dead characters back to life willy nilly. While most of the novels I had been reading (both on my own and those assigned) relied on plot arcs, grand themes, and character development, Candide was (is) a bizarre series of one-damn-thing-happening-after-another. Each chapter was its own little saga, an adventure writ in miniature, with attendant rises and falls. I loved it.

I reread Candide this weekend for no real reason in particular. I’ve read it a few times since high school, but it was never assigned again—not in college, not in grad school—which may or may not be a shame. I don’t know. In any case, the book still rings my bell; indeed, for me it’s the gold standard of picaresque novels, a genre I’ve come to dearly love. Perhaps I reread it with the bad taste of John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor still in my mouth. As I worked my way through that bloated mess, I just kept thinking, “Okay, Voltaire did it 200 years earlier, much better and much shorter.”

Revisiting Candide for the first time in years, I find that the book is richer, meaner, and far more violent than I’d realized. Even as a callow youth, I couldn’t miss Voltaire’s attack on the Age of Reason, sustained over a slim 120 pages or so. Through the lens of more experience (both life and reading), I see that Voltaire’s project in Candide is not just to satirize the Enlightenment’s ideals of rationality and the promise of progress, but also to actively destabilize those ideals through the structure of the narrative itself. Voltaire offers us a genuine adventure narrative and punctures it repeatedly, allowing only the barest slivers of heroism—and those only come from his innocent (i.e. ignorant) title character. Candide is topsy-turvy, steeped in both irony and violence.

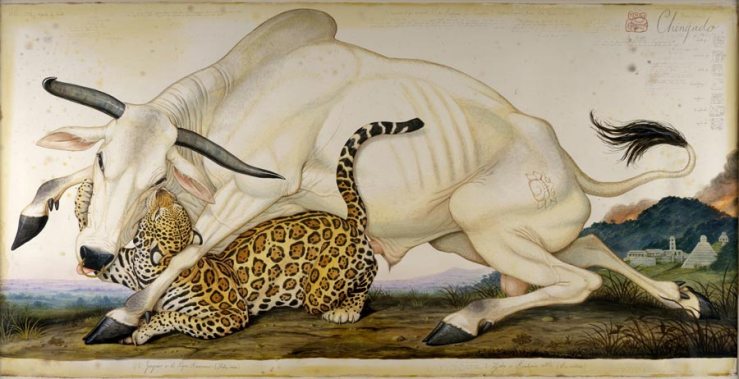

As a youth, the more surreal aspects of the violence appealed to me. (An auto-da-fé! Man on monkey murder! Earthquakes! Piracy! Cannibalizing buttocks!). The sexy illustrations in the edition I stole from my school helped intrigue me as well—

The self who read the book this weekend still loves a narrative steeped in violence—I can’t help it—Blood Meridian, 2666, the Marquis de Sade, Denis Johnson, etc.—but I realize now that, despite its occasional cartoonish distortions, Candide is achingly aware of the wars of Europe and the genocide underway in the New World. Voltaire by turns attacks rape and slavery, serfdom and warfare, always with a curdling contempt for the powers that be.

But perhaps I’ve gone too long though without quoting from this marvelous book, so here’s a passage from the last chapter that perhaps gives summary to Candide and his troupe’s rambling adventures: by way of context (and, honestly spoiling nothing), Candide and his friends find themselves eking out a living in boredom (although not despair) and finding war still raging around them (no shortage of heads on spikes); Candide’s Cunegonde is no longer fair but “growing uglier everyday” (and shrewish to boot!), Pangloss no longer believes that “it is the best of all worlds” they live in, yet he still preaches this philosophy, Martin finds little solace in the confirmation of his cynicism and misanthropy, and the Old Woman is withering away to death. The group finds their only entertainment comes from disputing abstract questions—

But when they were not arguing, their boredom became so oppressive that one day the old woman was driven to say, “I’d like to know which is worse: to be raped a hundred times by Negro pirates, to have one buttock cut off, to run the guantlet in the Bulgar army, to be whipped and hanged in an auto-da-fé, to be dissected, to be a galley slave—in short, to suffer all the miseries we’ve all gone through—or stay here and do nothing.

“That’s a hard question,” said Candide.

It’s amazing that over 200 years ago Voltaire posits boredom as an existential dilemma equal to violence; indeed, as its opposite. (I should stop and give credit here to Lowell Blair’s marvelous translation, which sheds much of the finicky verbiage you might find in other editions in favor of a dry, snappy deadpan, characterized in Candide’s rejoinder above). The book’s longevity might easily be attributed to its prescience, for Voltaire’s uncanny ability to swiftly and expertly assassinate all the rhetorical and philosophical veils by which civilization hides its inclinations to predation and straight up evil. But it’s more than that. Pointing out that humanity is ugly and nasty and hypocritical is perhaps easy enough, but few writers can do this in a way that is as entertaining as what we find in Candide. Beyond that entertainment factor, Candide earns its famous conclusion: “We must cultivate our garden,” young (or not so young now) Candide avers, a simple, declarative statement, one that points to the book’s grand thesis: we must work to overcome poverty, ignorance, and, yes, boredom. I’m sure, gentle, well-read reader, that you’ve read Candide before, but I’d humbly suggest to read it again.