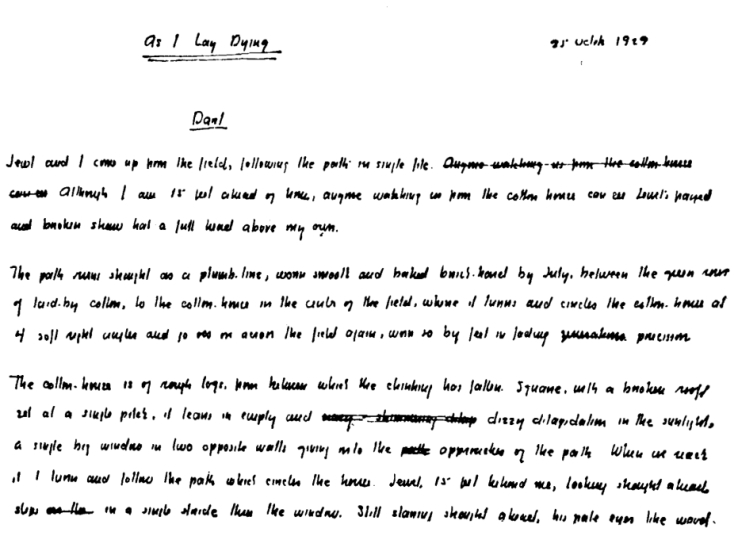

“Willie & Wade” by Donald Barthelme

Well we all had our Willie & Wade records ‘cept this one guy who was called Spare Some Change? ’cause that’s all he ever said and you don’t have no Willie & Wade records if the best you can do is Spare Some Change?

So we all took our Willie & Wade records down to the Willie & Wade Park and played all the great and sad Willie & Wade songs on portable players for the beasts of the city, the jumpy black squirrels and burnt-looking dogs and filthy, sick pigeons.

And I thought probably one day Willie or Wade would show up in person at the Willie & Wade Park to check things out, see who was there and what record this person was playing and what record that person was playing.

And probably Willie (or Wade) would just ease around checking things out, saying “Howdy” to this one and that one, and he’d see the crazy black guy in Army clothes who stands in the Willie & Wade Park and every ten minutes screams like a chicken, and Willie (or Wade) would just say to that guy, “How ya doin’ good buddy?” and smile, ’cause strange things don’t bother Willie, or Wade, one bit.

And I thought I’d probably go up to Willie then, if it was Willie, and tell him ’bout my friend that died, and how I felt about it at the time, and how I feel about it now. And Willie would say, “I know.”

And I would maybe ask him did he remember Galveston, and did he ever when he was a kid play in the old concrete forts along the sea wall with the giant cannon in them that the government didn’t want any more, and he’d say, “Sure I did.” And I’d say, “You ever work the Blue lay in San Antone?” and he’d say, “Sure I have.”

And I’d say, “Willie, don’t them microphones scare you, the ones with the little fuzzy sweaters on them?” And he’d say to me, “They scare me bad, potner, but I don’t let on.”

And then he (one or the other, Willie or Wade) would say, “Take care, good buddy,” and leave the Willie & Wade Park in his black limousine that the driver of had been waiting patiently in all this time, and I would never see him again, but continue to treasure, my life long, his great contributions.