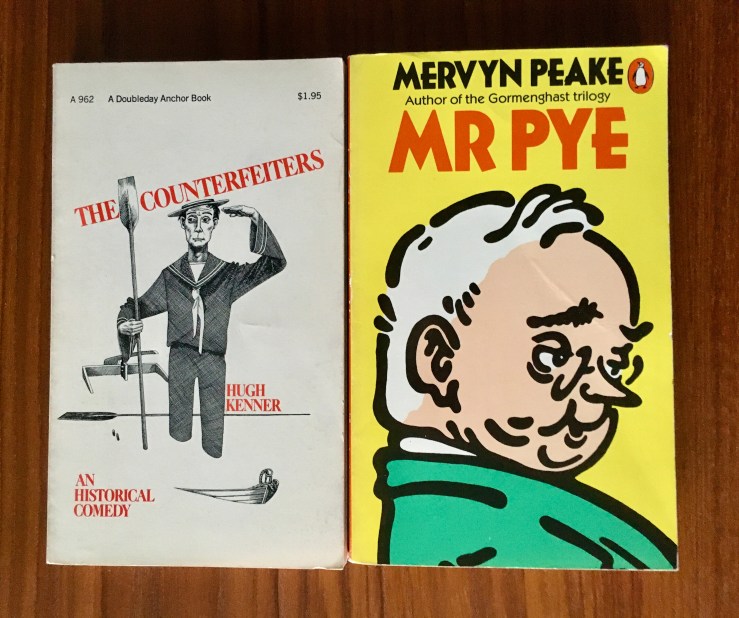

I went to my beloved used bookstore the first three Fridays in February, searching for a few things: novels by Rudolph Wurlitzer (no luck); Titus Alone, the last novel in Mervyn Peake’s “Gormenghast” trilogy (no luck; might have to order it); the penultimate Harry Potter novel (for my nine-year-old; plenty of copies—apparently his sister never made it that far).

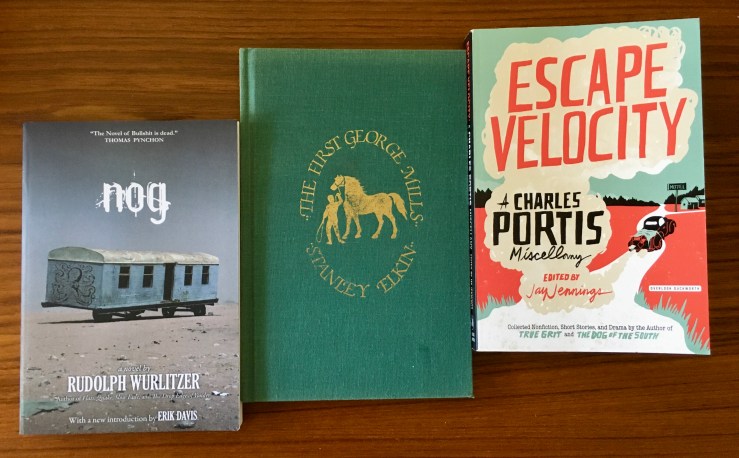

I did pick up Escape Velocity, a compendium of the late great Charles Portis’s journalism, essays, and short stories. There’s also a three-act play, Delray’s New Moon, which The Arkansas Repertory Theatre performed in 1996, and a 2001 interview with Portis that was part of The Gazette Project, which comprised a series of interviews with staff of the now-defunct Arkansas Gazette.

Portis worked for the Gazette early in his career, but it’s Civil Rights reporting for The New York Herald Tribune that’s more immediately compelling. Stories on the Klan rallies, Birmingham terror, and the assassination of Medgar Evers seem to add a new complexity and dimension to the South of Portis’s novels Norwood and The Dog of the South.

The essays in Escape Velocity seem especially promising, and also seem to inform the novels—at least the first one I read, “That New Sound from Nashville,” did. There’s something almost-gonzo about Portis’s technique (some of his early journalism vibrates with local color and ironic editorializing, too).

I’ve only read two of the five short stories in the collection. All are quite short, and the two I read feel like sketches, to be honest. Still, I’m interested in the fiction that Portis produced after his last novel Gringos, and three of the stories are from that era, along with the play Delray’s New Moon, which I hope will be richer than the stories I’ve read so far.

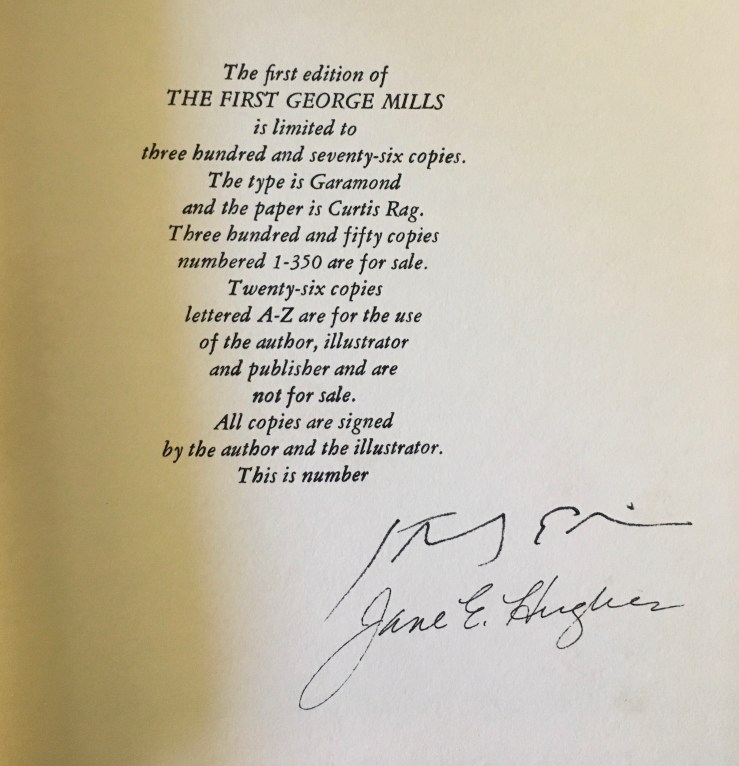

At the bookstore, I spied the gilt spine of The First George Mills, a 1980 oddity that comprises the first part (roughly 50 pages) of Stanley Elkin’s 1982 novel George Mills. The spine struck me as odd—so thin, so irregularly-shaped, etc. The book itself seemed like a novelty almost, and I was surprised to find Elkin’s signature at the end. I was even more surprised to find the signature of Jane Hughes, the apparent illustrator of this volume, whose illustrations do not appear in my copy. A bit of internet browsing seems to suggest that Hughes’s illustrations—of horses—were glued insets. Still, I was happy to forgo five bucks of my trade credit for Elkin’s signature.

When I got home from the bookstore a copy of Rudolph Wurlitzer’s cult classic 1969 novel Nog had arrived in the mail from Two Dollar Radio (along with a sticker and a bookmark and a thank you note—godbless indie publishers). I will be reading this book next, starting tonight. Here is the Thomas Pynchon blurb that made me interested in Wurlitzer:

Wow, this is some book, I mean it’s more than a beautiful and heavy trip, it’s also very important in an evolutionary way, showing us directions we could be moving in — hopefully another sign that the Novel of Bullshit is dead and some kind of re-enlightenment is beginning to arrive, to take hold. Rudolph Wurlitzer is really, really good, and I hope he manages to come down again soon, long enough anyhow to guide us on another one like Nog.

I did not go to the bookstore on this day, the last Friday of February 2020. I finished Gormenghast instead.

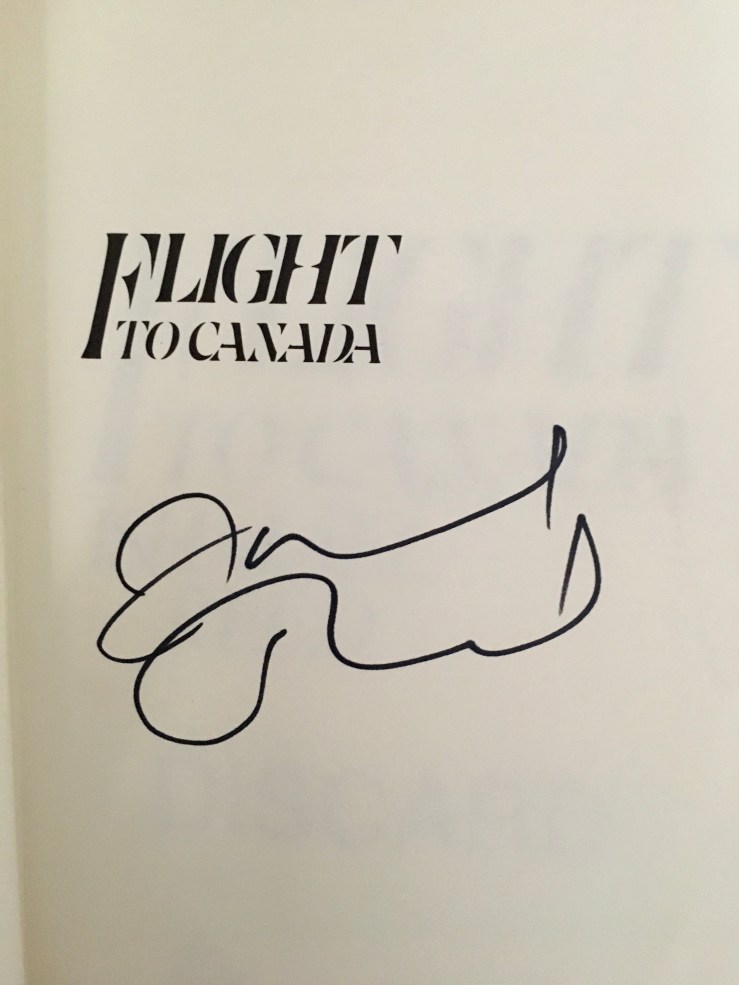

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all:

The technological anachronisms of Flight to Canada also serve to critique our framing of history. Our American Cousins plays live on broadcast TV, assassination and all: