Faulkner’s favorite drink is often listed as the julep, which is probably correct: his house in Oxford still displays his beloved metal julep cup. But his old standby was the toddy, which he describes “compounding … with ritualistic care.” It comes in two forms, hot and cold. Faulkner’s niece, Dean Faulkner Wells, clearly recalled her uncle making hot toddies and serving them to his ailing children on a silver tray. But unlike today, the cold toddy seems to have been the more popular in Faulkner’s day.

Recipe:

2 ounces of bourbon or white whiskey

4 ounces of water (cold or boiling)

If cold, 1 lemon slice; if hot, 1/2 lemon, both juice + rind

1 teaspoon of sugarThe key to a toddy, according to Faulkner, is that the sugar must be dissolved into a small amount of water before the whiskey is added, otherwise it “lies in a little intact swirl like sand at the bottom of the glass.” (One of Faulkner’s short stories, “An Error in Chemistry,” hinges on this point: a northern murderer, pretending to be a Southern gentleman, mistakenly mixes sugar with “raw whiskey”; the Southerners recognize his faux pas and immediately pounce on him.) Once the sugar is dissolved, the whiskey is poured over it. Top it off, to taste, with the remaining water—preferably “rainwater from a cistern.” Add lemon and serve in a heavy glass tumbler.

Category: Literature

“Hunting the Deceitful Turkey” — Mark Twain

“Hunting the Deceitful Turkey” — Mark Twain

When I was a boy my uncle and his big boys hunted with the rifle, the youngest boy Fred and I with a shotgun—a small single-barrelled shotgun which was properly suited to our size and strength; it was not much heavier than a broom. We carried it turn about, half an hour at a time. I was not able to hit anything with it, but I liked to try. Fred and I hunted feathered small game, the others hunted deer, squirrels, wild turkeys, and such things. My uncle and the big boys were good shots. They killed hawks and wild geese and such like on the wing; and they didn’t wound or kill squirrels, they stunned them. When the dogs treed a squirrel, the squirrel would scamper aloft and run out on a limb and flatten himself along it, hoping to make himself invisible in that way—and not quite succeeding. You could see his wee little ears sticking up. You couldn’t see his nose, but you knew where it was. Then the hunter, despising a “rest” for his rifle, stood up and took offhand aim at the limb and sent a bullet into it immediately under the squirrel’s nose, and down tumbled the animal, unwounded, but unconscious; the dogs gave him a shake and he was dead. Sometimes when the distance was great and the wind not accurately allowed for, the bullet would hit the squirrel’s head; the dogs could do as they pleased with that one—the hunter’s pride was hurt, and he wouldn’t allow it to go into the gamebag.

In the first faint gray of the dawn the stately wild turkeys would be stalking around in great flocks, and ready to be sociable and answer invitations to come and converse with other excursionists of their kind. The hunter concealed himself and imitated the turkey-call by sucking the air through the leg-bone of a turkey which had previously answered a call like that and lived only just long enough to regret it. There is nothing that furnishes a perfect turkey-call except that bone. Another of Nature’s treacheries, you see. She is full of them; half the time she doesn’t know which she likes best—to betray her child or protect it. In the case of the turkey she is badly mixed: she gives it a bone to be used in getting it into trouble, and she also furnishes it with a trick for getting itself out of the trouble again. When a mamma-turkey answers an invitation and finds she has made a mistake in accepting it, she does as the mamma-partridge does—remembers a previous engagement—and goes limping and scrambling away, pretending to be very lame; and at the same time she is saying to her not-visible children, “Lie low, keep still, don’t expose yourselves; I shall be back as soon as I have beguiled this shabby swindler out of the country.”

When a person is ignorant and confiding, this immoral device can have tiresome results. I followed an ostensibly lame turkey over a considerable part of the United States one morning, because I believed in her and could not think she would deceive a mere boy, and one who was trusting her and considering her honest. I had the single-barrelled shotgun, but my idea was to catch her alive. I often got within rushing distance of her, and then made my rush; but always, just as I made my final plunge and put my hand down where her back had been, it wasn’t there; it was only two or three inches from there and I brushed the tail-feathers as I landed on my stomach—a very close call, but still not quite close enough; that is, not close enough for success, but just close enough to convince me that I could do it next time. She always waited for me, a little piece away, and let on to be resting and greatly fatigued; which was a lie, but I believed it, for I still thought her honest long after I ought to have begun to doubt her, suspecting that this was no way for a high-minded bird to be acting. I followed, and followed, and followed, making my periodical rushes, and getting up and brushing the dust off, and resuming the voyage with patient confidence; indeed, with a confidence which grew, for I could see by the change of climate and vegetation that we were getting up into the high latitudes, and as she always looked a little tireder and a little more discouraged after each rush, I judged that I was safe to win, in the end, the competition being purely a matter of staying power and the advantage lying with me from the start because she was lame.

Along in the afternoon I began to feel fatigued myself. Neither of us had had any rest since we first started on the excursion, which was upwards of ten hours before, though latterly we had paused awhile after rushes, I letting on to be thinking about something else; but neither of us sincere, and both of us waiting for the other to call game but in no real hurry about it, for indeed those little evanescent snatches of rest were very grateful to the feelings of us both; it would naturally be so, skirmishing along like that ever since dawn and not a bite in the meantime; at least for me, though sometimes as she lay on her side fanning herself with a wing and praying for strength to get out of this difficulty a grasshopper happened along whose time had come, and that was well for her, and fortunate, but I had nothing—nothing the whole day.

More than once, after I was very tired, I gave up taking her alive, and was going to shoot her, but I never did it, although it was my right, for I did not believe I could hit her; and besides, she always stopped and posed, when I raised the gun, and this made me suspicious that she knew about me and my marksmanship, and so I did not care to expose myself to remarks.

I did not get her, at all. When she got tired of the game at last, she rose from almost under my hand and flew aloft with the rush and whir of a shell and lit on the highest limb of a great tree and sat down and crossed her legs and smiled down at me, and seemed gratified to see me so astonished.

I was ashamed, and also lost; and it was while wandering the woods hunting for myself that I found a deserted log cabin and had one of the best meals there that in my life-days I have eaten. The weed-grown garden was full of ripe tomatoes, and I ate them ravenously, though I had never liked them before. Not more than two or three times since have I tasted anything that was so delicious as those tomatoes. I surfeited myself with them, and did not taste another one until I was in middle life. I can eat them now, but I do not like the look of them. I suppose we have all experienced a surfeit at one time or another. Once, in stress of circumstances, I ate part of a barrel of sardines, there being nothing else at hand, but since then I have always been able to get along without sardines.

In the rare-poison room (Donald Barthelme)

“NOW I have been left sucking the mop again,” Jane blurted out in the rare-poison room of her mother’s magnificent duplex apartment on a tree-lined street in a desirable location. “I have been left sucking the mop in a big way. Hogo de Bergerac no longer holds me in the highest esteem. His highest esteem has shifted to another, and now he holds her in it, and I am alone with my malice at last. Face to face with it. For the first time in my history, I have no lover to temper my malice with healing balsam-scented older love. Now there is nothing but malice.” Jane regarded the floor-to-ceiling Early American spice racks with their neatly labeled jars of various sorts of bane including dayshade, scumlock, hyoscine, azote, hurtwort and milkleg. “Now I must witch someone, for that is my role, and to flee one’s role, as Gimbal tells us, is in the final analysis bootless. But the question is, what form shall my malice take, on this occasion? This braw February day? Something in the area of interpersonal relations would be interesting. Whose interpersonal relations shall I poison, with the tasteful savagery of my abundant imagination and talent for concoction? I think I will go around to Snow White’s house, where she cohabits with the seven men in a mocksome travesty of approved behavior, and see what is stirring there. If something is stirring, perhaps I can arrange a sleep for it — in the corner of a churchyard, for example.”

From Donald Barthelme’s novel Snow White.

A Short Riff on They Might Be Giants’ Album Flood (Book Acquired, 11.18.2013)

In the seventh grade, my friend Tilford gave me a copy of They Might Be Giant’s album Flood. This was in 1991, back when “alternative” music was far more varied than it is now. What I mean by this is that back in those halcyon days, we listened to anything we could get our ears to—and really listened. This meant TMBG, R.E.M, RHCP, KMFDM, Sonic Youth, The Pixies, Fugazi, the Dead Kennedys, The Dead Milkmen, The Meat Puppets, The Meatmen, The Minutemen—just anything different than what was on the radio. Lack of access to music meant that we listened to a wider diversity of bands than maybe Kids Today do. (These are all crotchety claims. Get off my lawn).

Anyway, Flood—the album, its freewheeling zaniness, its nasal vibe, its silliness, its diversity, its poppiness—so much of it is still imprinted on my brain. “Birdhouse in Your Soul” is probably the only TMBG song that I’ll still put on a mix CD (okay, that and “Minimum Wage”), but Flood is rich in its strange pop vibes. Songs like “Road Movie to Berlin” (later covered by Frank Black) and “They Might Be Giants” played on a loop in my brain in the early nineties. Other songs like the jokey cover “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” and “Particle Man” pointed the way to the kind of kid-friendly skewed pop that would define the second half of TMBG’s career. “You Racist Friend” is one of the most direct protest songs I’ve ever heard.

I’ve never forgiven TMBG for quitting two songs in to their set when I saw them in 1996. John Linnell was too ill to continue, and called the show off. In retrospect, I understand why—dude was sick, really sick (I can remember his face)—but for me it was an easy break with a band that lacked the art rock verve that I found more interesting in the late nineties. I could write They Might Be Giants off as kid music. That’s undoubtedly an unfair assessment though.

S. Alexander Reed and Philip Sandifer have written a new book (in the 33 1/3 series) on Flood. In the blurb, below, we get a clear overview of how important this record was—even if it isn’t discussed along with Sonic Youth’s Goo and Dirty, R.E.M.’s Green, or The Pixies’ last record (not to mention all the “grunge” bands that exploded after those records). Here’s the blurb:

For a few decades now, They Might Be Giants’ album Flood has been a beacon (or at least a nightlight) for people who might rather read than rock out, who care more about science fiction than Slayer, who are more often called clever than cool. Neither the band’s hip origins in the Lower East Side scene nor Flood’s platinum certification can cover up the record’s singular importance at the geek fringes of culture.

Flood’s significance to this audience helps us understand a certain way of being: it shows that geek identity doesn’t depend on references to Hobbits or Spock ears, but can instead be a set of creative and interpretive practices marked by playful excess—a flood of ideas.

The album also clarifies an historical moment. The brainy sort of kids who listened to They Might Be Giants saw their own cultural options grow explosively during the late 1980s and early 1990s amid the early tech boom and America’s advancing leftist social tides. Whether or not it was the band’s intention, Flood’s jubilant proclamation of an identity unconcerned with coolness found an ideal audience at an ideal turning point. This book tells the story.

“On the Surface of Things” — Wallace Stevens

S.D. Chrostowska’s Novel Permission Deconstructs the Episotolary Form

In trying to frame a review of S.D. Chrostowska’s novel Permission, I have repeatedly jammed myself against many of the conundrums that the book’s narrator describes, imposes, chews, digests, and synthesizes for her reader.

I have, for example, just now resisted the impulse to place the terms novel, narrator, and reader under radical suspicion. (I realize that the last sentence carries out the impulse even as it purports not to). Permission, thoroughly soaked in deconstruction, repeatedly places its own composition under radical suspicion.

This is maybe a bad start to a review.

Another description:

Permission pretends to be the emails that F.W. (later F. Wren, and even later, Fearn Wren) sends to an unnamed artist, a person she does not know, has never met, whom she contacts in a kind of affirmation of reciprocity tempered in the condition that her identity is “random and immaterial.” She aims to work out “an elementary philosophy of giving that is, by its very definition, anti-Western.” Her gift is the book she creates — “Permit me to write to you, today, beyond today,” the book begins.

Why?

What I want to measure—or, rather, what I want to obtain an impression of, since I do not claim exactitude of measurement for my results—is my own potential for creatio ad nihilum (creation fully within the limits of human ability, out of something and unto nothing). To rephrase my experimental question: can I give away what is inalienable from me (my utterance, myself) without the faintest expectation or hope of authority, solidarity, reciprocity?

F.W.’s project (Chrostowska’s project) here echoes Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction of giving, of the (im)possibility of authentic giving. F.W. wants to give, but she also deconstructs that impulse repeatedly. This is a novel (novel-essay, really) that cites Gilles Deleuze and Maurice Blanchot in its first twenty pages.

Her project is deconstruction; as she promises at the outset, her giving, her writing “is not solid, and does not lead to solidarity.” On the contrary,

it is solvent, and leads, through its progressive dissolution, towards the final solution of this writing (my work), which meanwhile becomes progressively less difficult, less obscure.

“Will it?” I asked in the margin of my copy. It does, perhaps.

After an opening that deconstructs its own opening, Chrostowska’s F.W. turns her attention to more concrete matters. We get a brief tour of cemeteries, a snapshot of the F.W.’s father (as a child) at a child’s funeral, a recollection of her first clumsy foray into fiction writing, a miniature memoir of a failed painter, color theory, the sun, the moon. We get an overview of our F.W.’s most intimate library—The Hound of the Baskervilles, a samizdat copy of Listy y Bialoleki [Letters from Bialoleka Prison], 1984. We get an analysis of Philip Larkin’s most famous line. Prisons, lunatic asylums, schools. Indian masks. Hamlet. More cemeteries.

My favorite entry in the book is a longish take on the “thingness of books,” a passage that concretizes the problems of writing—even thinking—after others. I think here of Blanchot’s claim that, ” No sooner is something said than something else must be said to correct the tendency of all that is said to become final.”

The most intriguing passages in Permission seem to pop out of nowhere, as Chrostowska turns her keen intellect to historical or aesthetic objects. These are often accompanied by black and white photographs (sometimes gloomy, even murky), recalling the works of W.G. Sebald, novel-essays that Permission follows in its form (and even tone). Teju Cole—who also clearly followed Sebald in his wonderful novel Open City—provides the blurb for Permission, comparing it to the work of Sebald’s predecessors, Thomas Browne and Robert Burton. There’s a pervasive melancholy here too. Permission, haunted by history, atrocity, memory, and writing itself, is often dour. The novel-essay is discursive but never freewheeling, and by constantly deconstructing itself, it ironically creates its own center, a decentered center, a center that initiates and then closes the work—dissolves the book.

Permission, often bleak and oblique, essentially plotless (a ridiculous statement this, plotless—this book is its own plot (I don’t know if that statement makes any sense; it makes sense to me, but I’ve read the book—the book is plotless in the conventional sense of plotedness, but there is a plot, a tapestry that refuses to yield one big picture because its threads must be unthreaded—dissolved to use Chrostowska’s metaphor)—where was I?—Yes, okay, Permission, as you undoubtedly have determined now, you dear, beautiful, bright thing, is Not For Everyone. However, readers intrigued by the spirit of (the spirit of) writing may appreciate and find much to consider in this deconstruction of the epistolary form.

Permission is new from The Dalkey Archive.

Vasilisa the Beautiful at the Hut of Baba Yaga — Ivan Bilibin

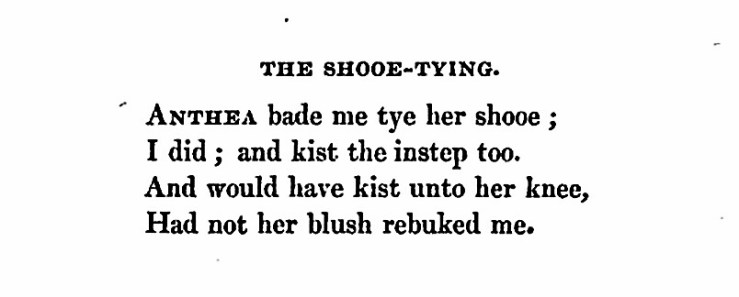

“The Shooe-Tying” — Robert Herrick

More Tom Clark (Books Acquired, 11.16.2013)

Last week I picked up more Tom Clark books. Devouring these things. I lied to myself that I was buying Paradise Resisted for a friend (I didn’t give it to him; I did give him a copy of Blood Meridian though). Junkets on a Sad Planet is a Very Strange Book.

A poem from Paradise:

“Another orange juice, with a little vodka in it this time” (Donald Barthelme)

SNOW WHITE had another glass of healthy orange juice. “From now on I deny myself to them. These delights. I maintain an esthetic distance. No more do I trip girlishly to their bed in the night, or after lunch, or in the misty mid-morning. Not that I ever did. It was always my whim which governed those gregarious encounters summed up so well by Livy in the phrase, vae victis. I congratulate myself on that score at least. And no more will I chop their onions, boil their fettucini, or marinate their flank steak. No more will I trudge about the house pursuing stain. No more will I fold their lingerie in neat bundles and stuff it away in the highboy. I am not even going to speak to them, now, except through third parties, or if I have something special to announce — a new nuance of my mood, a new vagary, a new extravagant caprice. I don’t know what such a policy will win me. I am not even sure I wish to implement it. It seems small and mean-spirited. I have conflicting ideas. But the main theme that runs through my brain is that what is, is insufficient. Where did that sulky notion come from? From the rental library, doubtless. Perhaps the seven men should have left me in the forest. To perish there, when all the roots and berries and rabbits and robins had been exhausted. If I had perished then, I would not be thinking now. It is true that there is a future in which I shall inevitably perish. There is that. Thinking terminates. One shall not always be leaning on one’s elbow in the bed at a quarter to four in the morning, wondering if the Japanese are happier than their piglike Western contemporaries. Another orange juice, with a little vodka in it this time.”

From Donald Barthelme’s novel Snow White.

Jason Schwartz Interviewed at 3:am Magazine

3:am Magazine has published an interview with novelist Jason Schwartz. Schwartz’s latest, John the Posthumous, is my favorite book of 2013. In the interview, Jason Lucarelli talks with Schwartz about John the Posthumous, his experiences with Gordon Lish, and teaching writing. The final answer of the interview though is my favorite moment—it reads like a wonderful and bizarre microfiction. Here it is, sans context:

This comes to mind: long ago, in New York, I taught middle school for a year. Rough and tumble sort of place. Lots of mischief, and no textbooks, as these had all been lost or destroyed or thrown out into a courtyard, where—I may be revising the memory slightly—there was a great pile of books, a pile nearly one story high. So it was upon the teacher to scratch out lessons on the blackboard. This was transcription, the transcription of many items, all these chapters from the absent books. And once this had been accomplished, once the blackboard had been covered with words, first thing in the morning, it was upon the teacher to guard the blackboard all day. So what to do when the fistfight breaks out? You know how people gather around. The teacher now fears the press of bodies, and the tendency of bodies to smudge, or even erase, words. Stop the fight or protect the blackboard? This seemed to me, at the time, the central educational dilemma. If you’re lucky, the fracas is close by, and you might arrange things accordingly—one hand here and one hand there, finding yourself in various complicated postures. I never managed that to successful effect. And perhaps all this explains why, in the old country, contortionists were always thought the best schoolteachers. Anyway, Mr. O’Riley’s room has been set afire in the meantime, or Mrs. Wilson has been trampled in the stairwell. The day would pass in that fashion, and then I would go home and write about postage stamps and Judas Iscariot.

Read/Listen to JG Ballard’s “The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race”

Author’s note. The assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, raised many questions, not all of which were answered by the Report of the Warren Commission. It is suggested that a less conventional view of the events of that grim day may provide a more satisfactory explanation. Alfred Jarry’s “The Crucifixion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race” gives us a useful lead.

Oswald was the starter.

From his window above the track he opened the race by firing the starting gun. It is believed that the first shot was not properly heard by all the drivers. In the following confusion, Oswald fired the gun two more times, but the race was already underway.

Kennedy got off to a bad start.

There was a governor in his car and its speed remained constant at about fifteen miles an hour. However, shortly afterwards, when the governor had been put out of action, the car accelerated rapidly, and continued at high speed along the remainder of the course.

Read the rest of JG Ballard’s short story “The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race” (and the Jarry text)—or let Miette read it to you.

“The Blind Pensioners at Quinze Vingt,” A Philosophical Digression by Voltaire

“The Blind Pensioners at Quinze Vingt” by Voltaire

A SHORT DIGRESSION.—When the hospital of the Quinze Vingt was first founded, the pensioners were all equal, and their little affairs were concluded upon by a majority of votes. They distinguished perfectly by the touch between copper and silver coin; they never mistook the wine of Brie for that of Burgundy. Their sense of smelling was finer than that of their neighbors who had the use of two eyes. They reasoned very well on the four senses; that is, they knew everything they were permitted to know, and they lived as peaceably and as happily as blind people could be supposed to do. But unfortunately one of their professors pretended to have clear ideas in respect to the sense of seeing, he drew attention; he intrigued; he formed enthusiasts; and at last he was acknowledged chief of the community. He pretended to be a judge of colors, and everything was lost.

This dictator of the Quinze Vingt chose at first a little council, by the assistance of which he got possession of all the alms. On this account, no person had the resolution to oppose him. He decreed, that all the inhabitants of the Quinze Vingt were clothed in white. The blind pensioners believed him; and nothing was to be heard but their talk of white garments, though, in fact, they possessed not one of that color. All their acquaintance laughed at them. They made their complaints to the dictator, who received them very ill; he rebuked them as innovators, freethinkers, rebels, who had suffered themselves to be seduced by the errors of those who had eyes, and who presumed to doubt that their chief was infallible. This contention gave rise to two parties.

To appease the tumult, the dictator issued a decree, importing that all their vestments were red. There was not one vestment of that color in the Quinze Vingt. The poor men were laughed at more than ever. Complaints were again made by the community. The dictator rushed furiously in; and the other blind men were as much enraged. They fought a long time; and peace was not restored until the members of the Quinze Vingt were permitted to suspend their judgments in regard to the color of their dress.

A deaf man, reading this little history, allowed that these people, being blind, were to blame in pretending to judge of colors; but he remained steady to his own opinion, that those persons who were deaf were the only proper judges of music.

Invisible Bust of Voltaire — Salvador Dali

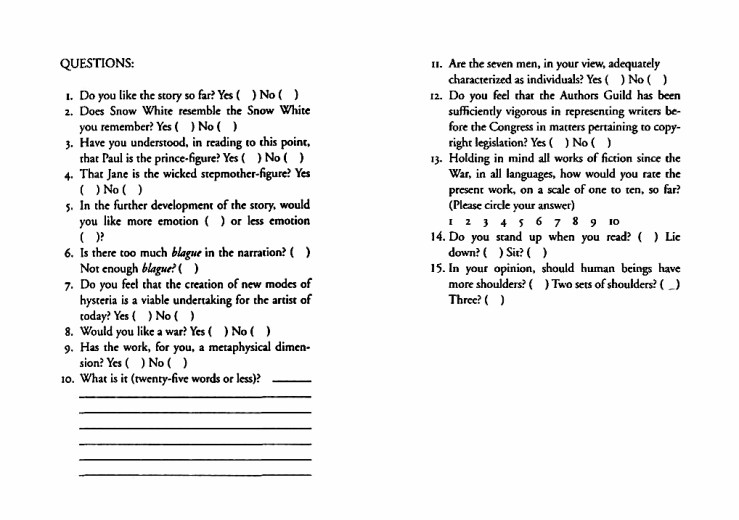

Questions (Donald Barthelme’s Snow White)

I Will Marry You (Beauty and the Beast) — Edmund Dulac