July 20th.–A drive yesterday afternoon to a pond in the vicinity of Augusta, about nine miles off, to fish for white perch. Remarkables: the steering of the boat through the crooked, labyrinthine brook, into the open pond,–the man who acted as pilot,–his talking with B—- about politics, the bank, the iron money of “a king who came to reign, in Greece, over a city called Sparta,”–his advice to B—- to come amongst the laborers on the mill-dam, because it stimulated them “to see a man grinning amongst them.” The man took hearty tugs at a bottle of good Scotch whiskey, and became pretty merry. The fish caught were the yellow perch, which are not esteemed for eating; the white perch, a beautiful, silvery, round-backed fish, which bites eagerly, runs about with the line while being pulled up, makes good sport for the angler, and an admirable dish; a great chub; and three horned pouts, which swallow the hook into their lowest entrails. Several dozen fish were taken in an hour or two, and then we returned to the shop where we had left our horse and wagon, the pilot very eccentric behind us. It was a small, dingy shop, dimly lighted by a single inch of candle, faintly disclosing various boxes, barrels standing on end, articles hanging from the ceiling; the proprietor at the counter, whereon appear gin and brandy, respectively contained in a tin pint-measure and an earthenware jug, with two or three tumblers beside them, out of which nearly all the party drank; some coming up to the counter frankly, others lingering in the background, waiting to be pressed, two paying for their own liquor and withdrawing. B—- treated them twice round. The pilot, after drinking his brandy, gave a history of our fishing expedition, and how many and how large fish we caught. B—- making acquaintances and renewing them, and gaining great credit for liberality and free-heartedness,–two or three boys looking on and listening to the talk,–the shopkeeper smiling behind his counter, with the tarnished tin scales beside him,–the inch of candle burning down almost to extinction. So we got into our wagon, with the fish, and drove to Robinson’s tavern, almost five miles off, where we supped and passed the night In the bar-room was a fat old countryman on a journey, and a quack doctor of the vicinity, and an Englishman with a peculiar accent. Seeing B—-‘s jointed and brass-mounted fishing-pole, he took it for a theodolite, and supposed that we had been on a surveying expedition. At supper, which consisted of bread, butter, cheese, cake, doughnuts and gooseberry-pie, we were waited upon by a tall, very tall woman, young and maiden-looking, yet with a strongly outlined and determined face. Afterwards we found her to be the wife of mine host. She poured out our tea, came in when we rang the table-bell to refill our cups, and again retired. While at supper, the fat old traveller was ushered through the room into a contiguous bedroom. My own chamber, apparently the best in the house, had its walls ornamented with a small, gilt-framed, foot-square looking-glass, with a hair-brush hanging beneath it; a record of the deaths of the family written on a black tomb, in an engraving, where a father, mother, and child were represented in a graveyard, weeping over said tomb; the mourners dressed in black, country-cut clothes; the engraving executed in Vermont. There was also a wood engraving of the Declaration of Independence, with fac-similes of the autographs; a portrait of the Empress Josephine, and another of Spring. In the two closets of this chamber were mine hostess’s cloak, best bonnet, and go-to-meeting apparel. There was a good bed, in which I slept tolerably well, and, rising betimes, ate breakfast, consisting of some of our own fish, and then started for Augusta. The fat old traveller had gone off with the harness of our wagon, which the hostler had put on to his horse by mistake. The tavern-keeper gave us his own harness, and started in pursuit of the old man, who was probably aware of the exchange, and well satisfied with it.

Our drive to Augusta, six or seven miles, was very pleasant, a heavy rain having fallen during the night, and laid the oppressive dust of the day before. The road lay parallel with the Kennebec, of which we occasionally had near glimpses. The country swells back from the river in hills and ridges, without any interval of level ground; and there were frequent woods, filling up the valleys or crowning the summits. The land is good, the farms look neat, and the houses comfortable. The latter are generally but of one story, but with large barns; and it was a good sign, that, while we saw no houses unfinished nor out of repair, one man at least had found it expedient to make an addition to his dwelling. At the distance of more than two miles, we had a view of white Augusta, with its steeples, and the State-House, at the farther end of the town. Observable matters along the road were the stage,–all the dust of yesterday brushed off, and no new dust contracted,–full of passengers, inside and out; among them some gentlemanly people and pretty girls, all looking fresh and unsullied, rosy, cheerful, and curious as to the face of the country, the faces of passing travellers, and the incidents of their journey; not yet damped, in the morning sunshine, by long miles of jolting over rough and hilly roads,–to compare this with their appearance at midday, and as they drive into Bangor at dusk; two women dashing along in a wagon, and with a child, rattling pretty speedily down hill;–people looking at us from the open doors and windows;–the children staring from the wayside;–the mowers stopping, for a moment, the sway of their scythes;–the matron of a family, indistinctly seen at some distance within the house her head and shoulders appearing through the window, drawing her handkerchief over her bosom, which had been uncovered to give the baby its breakfast,–the said baby, or its immediate predecessor, sitting at the door, turning round to creep away on all fours;–a man building a flat-bottomed boat by the roadside: he talked with B—- about the Boundary question, and swore fervently in favor of driving the British “into hell’s kitchen” by main force.

Colonel B—-, the engineer of the mill-dam, is now here, after about a fortnight’s absence. He is a plain country squire, with a good figure, but with rather a heavy brow; a rough complexion; a gait stiff, and a general rigidity of manner, something like that of a schoolmaster. He originated in a country town, and is a self-educated man. As he walked down the gravel-path to-day, after dinner, he took up a scythe, which one of the mowers had left on the sward, and began to mow, with quite a scientific swing. On the coming of the mower, he laid it down, perhaps a little ashamed of his amusement. I was interested in this; to see a man, after twenty-five years of scientific occupation, thus trying whether his arms retained their strength and skill for the labors of his youth,–mindful of the day when he wore striped trousers, and toiled in his shirt-sleeves,–and now tasting again, for pastime, this drudgery beneath a fervid sun. He stood awhile, looking at the workmen, and then went to oversee the laborers at the mill-dam.

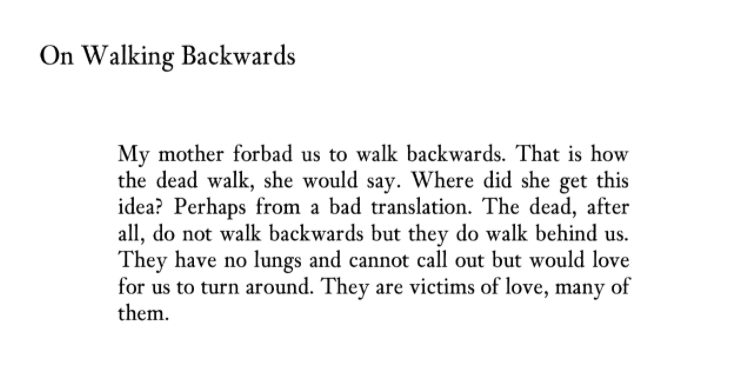

I would worry about being on such a list, because I like to write uncanonical things, things that oppose the general flow of the culture. I would certainly be happy to believe that I could share the same halls or bookcase or something with some of the writers whom I admire so much, but I would feel very insecure about my place there…I”m not sure that I want my books to be patted on the back by lots of scholars in the academy and told, “There, there, these are okay.” …My feelings about things like this are more the sort of thing I have about my children: I would be a little disturbed if everybody loved them.

In his

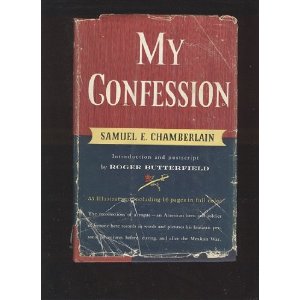

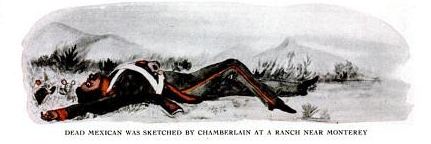

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

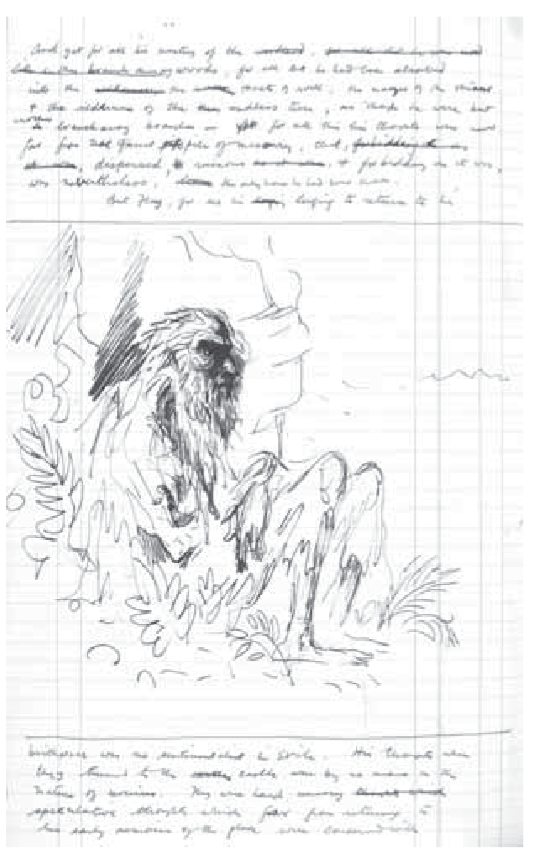

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

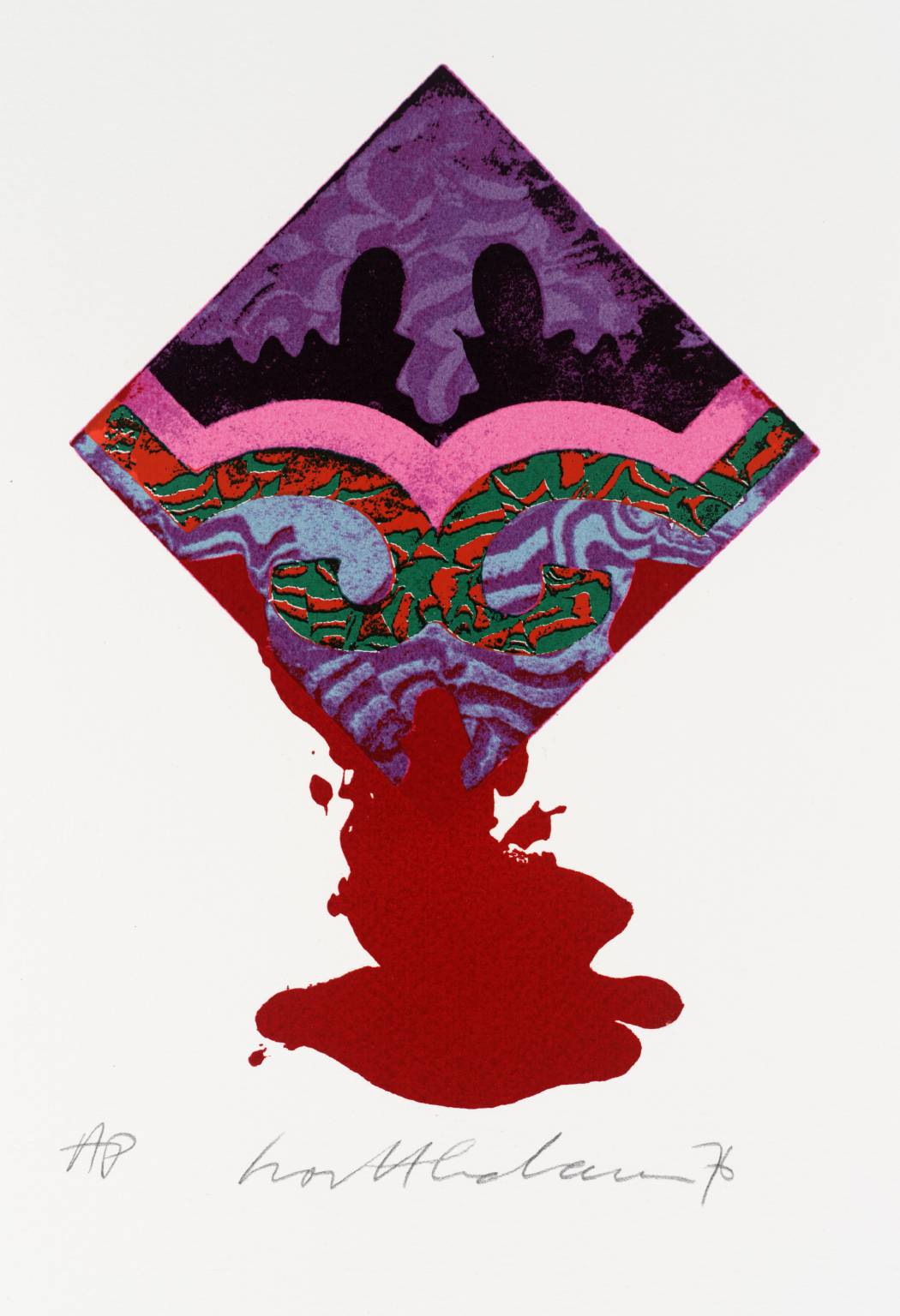

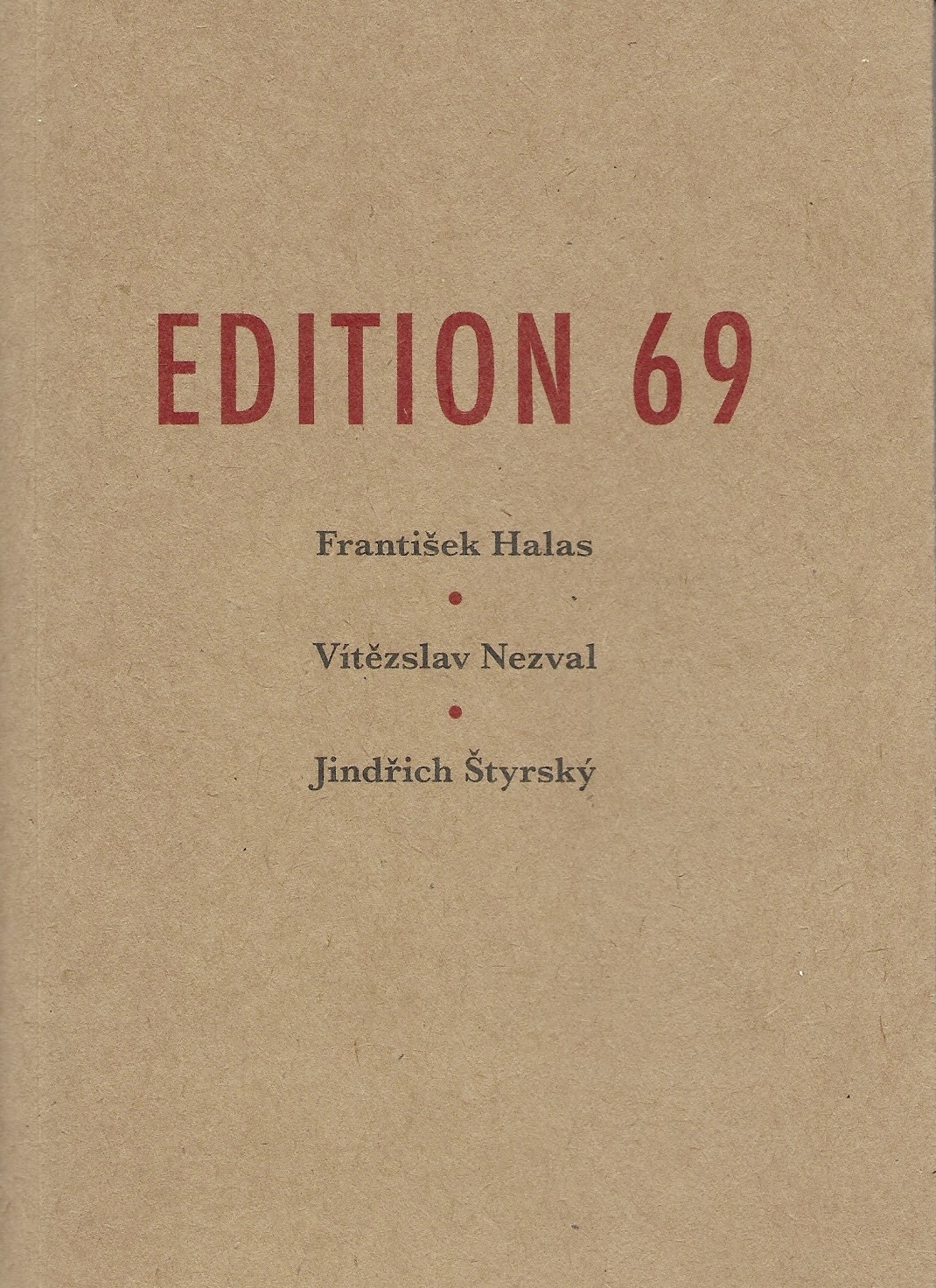

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s