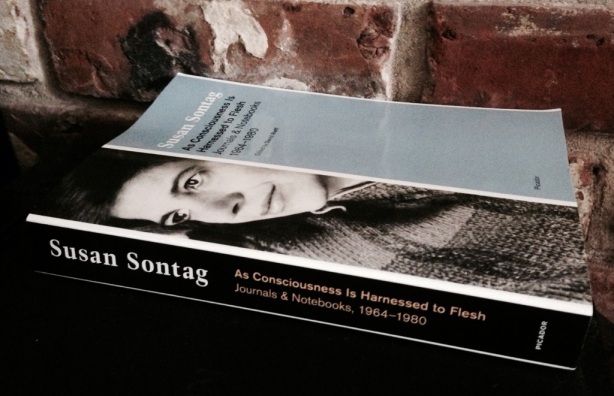

1. “In my more extravagant moments,” writes David Rieff in his introduction to Susan Sontag’s As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh, “I sometimes think that my mother’s journals, of which this is the second of three volumes, are not just the autobiography she never got around to writing…but the great autobiographical novel she never cared to write.”

2. In my review of Reborn, the first of the trilogy Rieff alludes to, I wrote, “Don’t expect, of course, to get a definitive sense of who Sontag was, let alone a narrative account of her life here. Subtitled Journals & Notebooks 1947-1963, Reborn veers closer to the “notebook” side of things.”

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh is far closer to the ‘notebook’ side of things too, which I think most readers (or maybe I just mean me here) will appreciate.

3. I mean, this isn’t the autobiographical novel that Rieff suggests it might be (except of course it is).

Consciousness/Flesh offers something better: access to Sontag’s consciousness in its prime, not quite ripe, but full, heavy, bursting with intellectual energy, her mind attuned to (and attuning) the tumult of the time the journals cover, 1964 through 1980.

It’s an autobiography stripped of the pretense of presentation; it’s a novel stripped of the pretense of storytelling.

4. Sontag’s intellect and spirit course through the book’s 500 pages, eliding any distinction between lives personal and professional. “What sex is the ‘I’?” she writes, “Who has the right to say ‘I’?” The journals see her working through (if not resolving, thankfully) such issues.

5. An entry from late 1964, clearly background for Sontag’s seminal essay “Notes on Camp” (itself a series of notes), moves through a some thoughts on artists and poets, from Warhol to Breton to Duchamp (“DUCHAMP”) to simply “Style,” which, Rieff’s editorial note tells us, has a box drawn around it. The entry then moves to define

Work of Art

An experiment, a research (solving a “problem”) vs. form of a play

—before turning to a series of notes on the films of Michelangelo Antonioni.

6. A page or two later (1965) delivers the kind of gold vein we wish to discover in author’s notebooks:

PLOTS & SITUATIONS

Redemptive friendship (two women)

Novel in letters: the recluse-artist and his dealer a clairvoyant

A voyage to the underworld (Homer, Vergil [sic], Steppenwolf)

Matricide

An assassination

A collective hallucination (Story)

A theft

A work of art which is really a machine for dominating human beings

The discovery of a lost mss.

Two incestuous sisters

A space ship has landed

An ageing movie actress

A novel about the future. Machines. Each man has his own machine (memory bank, codified decision maker, etc.) You “play the machine. Instant everything.

Smuggling a huge art-work (painting? Sculpture?) out of the country in pieces—called “The Invention of Liberty”

A project: sanctity (based on SW [Simone Weil]—with honesty of Sylvia Plath—only way to solve sex “I” is talk about it

Jealousy

7. The list above—and there’s so much material like it in Consciousness/Flesh—is why I love author’s notebooks, We get to see the raw material here and imagine along with the writer (if we choose), free of the clutter and weight of execution, of prose, of damnable detail.

There’s something joyfully cryptic about Sontag’s notes, like the solitary entry “…Habits of despair” in late July of 1970—or a few months later: “A convention of mutants (Marvel comics).”

If we wish we can puzzle the notes out, treat them as clues or keys that fit to the work she was publishing at the time or to the personal circumstances of her private life. Or (and to be clear, I choose this or) we can let these notes stand as strange figures in an unconventional autobiographical novel.

8. Those looking for more direct material about Sontag’s life (and really, why do you want more and what more do you want?) will likely be disappointed—everything here is oblique (lovely, lovely oblique).

Still, there are moments of intense personal detail, like this 1964 entry where Sontag describes her body:

Body type

- Tall

- Low blood pressure

- Needs lots of sleep

- Sudden craving for pure sugar (but dislike desserts—not a high enough concentration)

- Intolerance for liquor

- Heavy smoking

- Tendency to anemia

- Heavy protein craving

- Asthma

- Migraines

- Very good stomach—no heartburn, constipation, etc.

- Negligible menstrual cramps

- Easily tired by standing

- Like heights

- Enjoy seeing deformed people (voyeuristic)

- Nailbiting

- Teeth grinding

- Nearsighted, astigmatism

- Frileuse (very sensitive to cold, like hot summers)

- Not very sensitive to noise (high degree of selective auditory focus)

There’s more autobiographical detail in that list than anyone craving a lurid expose could (should) hope for.

9. For many readers (or maybe I just mean me here) Consciousness/Flesh will be most fascinating as a curatorial project.

Sontag offers her list of best films (not in order),her ideal short story collection, and more. The collection often breaks into lists—like the ones we see above—but also into names—films, authors, books, essays, ideas, etc.

10. At times, Consciousness/Flesh resembles something close to David Markson’s so-called “notecard” novels (Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, The Last Novel):

Napoleon’s wet, chubby back (Tolstoy).

and

Wordsworth’s ‘wise passiveness.’

and

Nabokov talks of minor readers. ‘There must be minor readers because there are minor writers.’

and

Camus (Notebooks, Vol. II): ‘Is there a tragic dilettante-ism?'”

and

‘To think is to exaggerate.’ — Valéry.

and so on…

11. Sometimes, the lists Sontag offers—

(offers is not the right verb at all here—these are Sontag’s personal journals and notebooks, her private ideas, material never intended for public consumption, but yes we are greedy, yes; and some of us (or maybe I just mean me here) are greedier than others, far more interested in her private ideas and notes and lists than the essays and stories and novels she generated from them—and so no, she didn’t offer this, my verb is all wrong)

—sometimes Sontag [creates/notes/generates] very personal lists, like “Movies I saw as a child, when they came out” (composed 11/25/65). There’s something tender here, imagining the child Sontag watching Fantasia or Rebecca or Citizen Kane or The Wizard of Oz in the theater; and then later, the adult Sontag, crafting her own lists, making those connections between past and present.

12. While Reborn showcased the intimate thoughts of a nascent (and at times naïve) intellect, Consciousness/Flesh shows us an assured writer at perhaps her zenith. In September of 1975, Sontag defines herself as a writer:

I am an adversary writer, a polemical writer. I write to support what is attacked, to attack what is acclaimed. But thereby I put myself in an emotionally uncomfortable position. I don’t, secretly, hope to convince, and can’t help being dismayed when my minority taste (ideas) becomes majority taste (ideas): then I want to attack again. I can’t help but be in an adversary relation to my own work.

13. Readers looking for a memoir or biography might be disappointed in Consciousness/Flesh; readers who seek to scrape its contours for “wisdom” (or worse, writing advice) should be castigated.

But As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh will reward those readers who take it on its own terms as an oblique, discursive (and incomplete) record of Sontag’s brilliant mind.

I’ll close this riff with one last note from the book, a fitting encapsulation of the relationship between reader and author—and, most importantly, author-as-reader-and-rereader:

Recycling one’s own life with books.

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh is new in trade paperback from Picador; you can read excerpts from the book at their site.