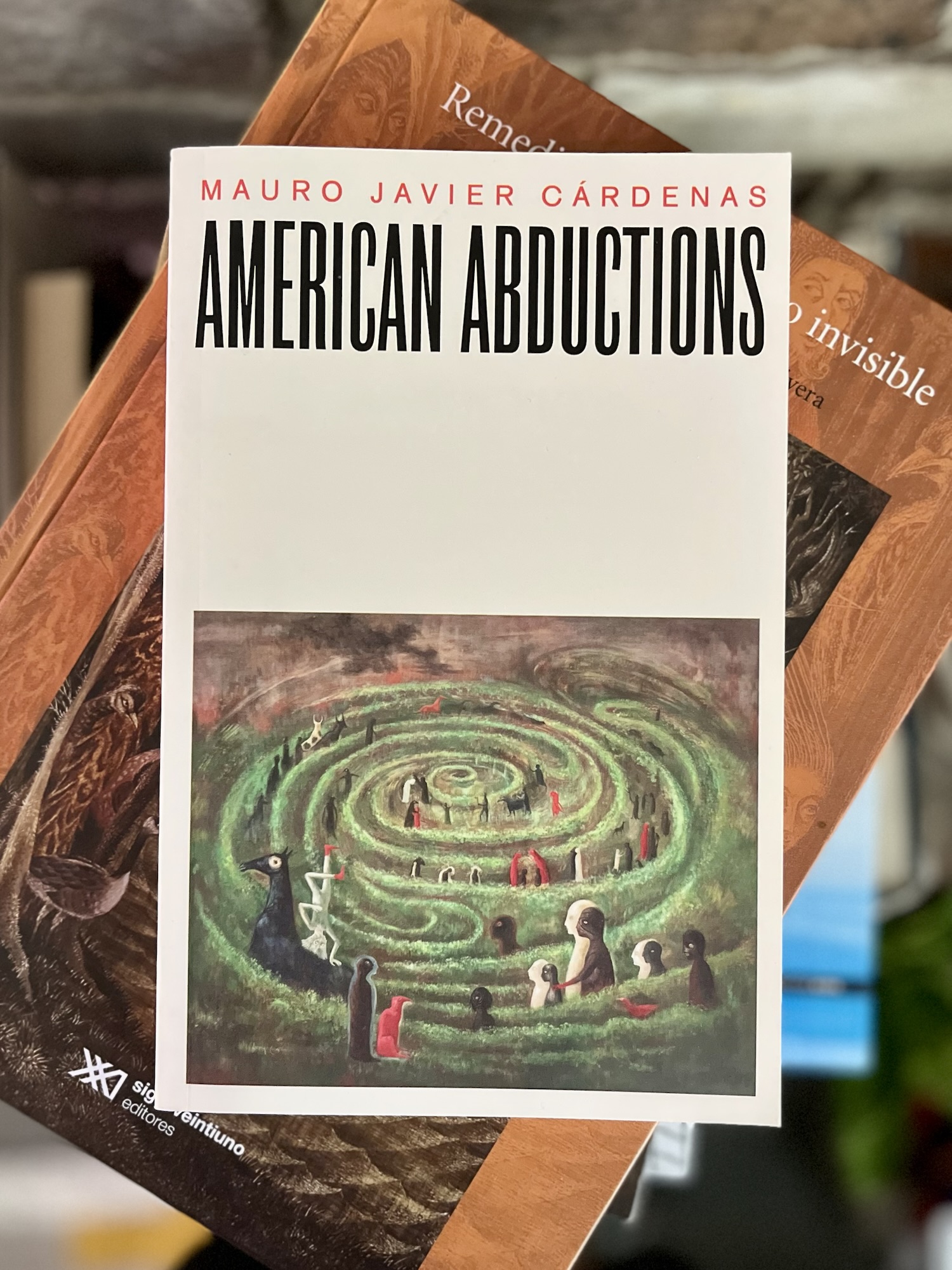

Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s American Abductions is a novel of relentless, layered consciousness, its immersive, labyrinthine sentences pulling the reader into a fugue of voices, memories, and anxieties. American Abductions takes place in a proximal version of the United States, a digital carceral state where palefaced goons kidnap Latin Americans. Sometimes the abductees are deported; sometimes they are disappeared. Sometimes they tell stories.

The dystopia here is hardly a YA world-building exercise full of hope and heroics. Instead, the novel moves through fragmented, fevered perspectives, primarily those of sisters Ada and Eva their disappeared father, Antonio, a novelist abducted by the Pale Americans, the faceless bureaucratic enforcers of this new regime. The novel oscillates between Ada and Eva’s attempts to reconstruct what happened, Antonio’s own recursive, metafictional writing, and interjections from various other voices—family members, interrogators, digital surveillance logs—until the narrative itself becomes a reflection of the fragmented reality the characters are trapped within.

Yes, American Abductions is bleak, but it is not merely dystopian horror. Cárdenas builds his world through a dizzying interplay of language, wielding the long, unspooling sentence with the precision of Bernhard, Krasznahorkai, and Sebald. Each chapter is a single winding comma splice that careens from realism to surrealism. Cárdenas’s run-ons layer and loop back on themselves, rhetorically mirroring the characters’ attempts to make sense of their unraveling world.

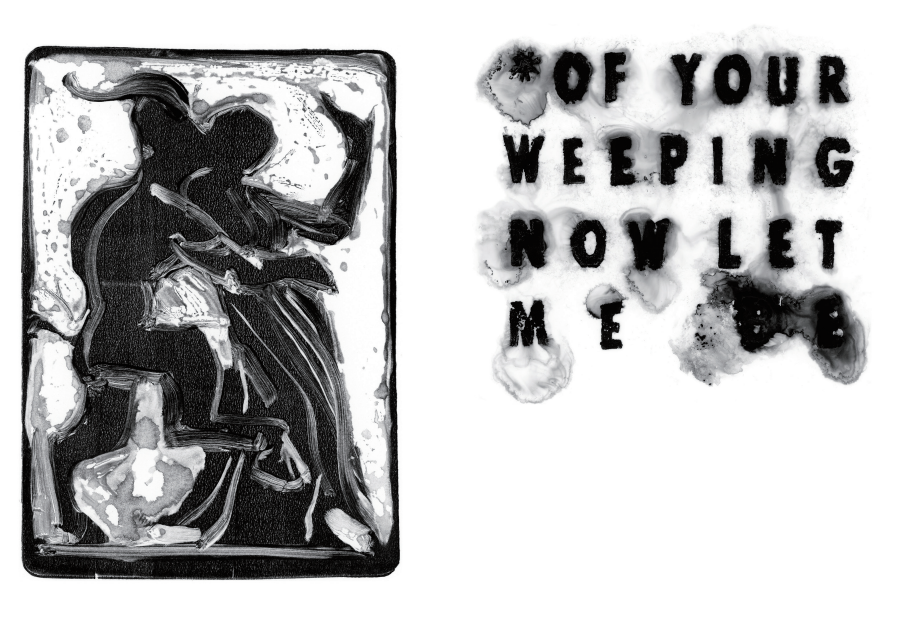

The book moves forward with an absurdist energy that resists despair, its rhythms and repetitions building not just a critique of authoritarian power but something stranger, something more human—an exploration of consciousness itself, an attempt, perhaps, to make a grand “statement of missingnessness,” to borrow one of the character’s phrases.

The effect is hypnotic, dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish, but often, surprisingly, very funny. There is a dark, absurdist humor in the way bureaucratic jargon collides with intimate grief, in the way digital surveillance reports are laced with banal observations, in the way Antonio’s own metafictional writing seems to both clarify and obscure the truth of his disappearance. The novel is not just about authoritarian violence but about how language itself is manipulated under such regimes—how it obfuscates, justifies, betrays, resists. At times, American Abductions reads like a political thriller rewritten as a fever dream, at others, like a linguistic experiment that spirals into a meditation on memory, exile, and state terror.

American Abductions is not just unsettlingly prescient. Rather, it obliquely underscores the U.S. surveillance state’s direct lineage to Latin America’s Dirty Wars. Governments systematically disappeared those deemed threats to the state—intellectuals, activists, ordinary people unlucky enough to be caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Cárdenas’s dystopia does not just critique contemporary American immigration policies; it situates them within a long history of state-sanctioned violence in the Americas.

The novel’s themes take on chilling immediacy when considered alongside the real-world abductions of those who speak truth to power, like Mahmoud Khalil and Rumeysa Ozturk. Indeed, the disturbing video footage of Ozturk’s kidnapping by masked men this week has gone viral, echoing the opening of American Abductions, wherein we learn that Ada has captured “that moment when the American abductors captured her father as he was driving her and her sister to school, which she recorded on her phone.” Ada’s video goes viral, mutates, becomes its own beast:

…and later, after her father had been captured and hundreds of thousands of people around the world were watching her video of her father asking what have I done, officer, the supervisory official probably watched it too and left an anonymous comment below it that said ice / ice baby great job ICE, illegal is illegal and wrong is wrong bye you forgot the crybaby in the backseat, for years Ada arguing in her mind with the thousands of messages berating her and her father, even after she discovered some of the comments had been manufactured by bots controlled by a Pale American in Salt Lake City — twelve million to go please continue to remove the illegal alien infestation — except the comments by Doctor Sueño, of course, which made no sense to anyone but her, just as it made no sense to anyone but her to feel, for no more than a few seconds, proud that the supervisory official of the supervisory official of the supervisory official in an agency building had taken time out of his busy schedule to focus on her father — if enough time passes, Doctor Sueño says, even the most preposterous possibilities will navigate the sea of your mind — cry like an eagle / to the sea — just as it made no sense to anyone but her to laugh at some of the videos her video had spawned for instance the video of her video but with sappy music instead of her sister politely asking the abductors where were they taking her father, as if someone figured hey no one’s going to feel sorry enough for you people let me add sad violin music to the video of your father saying I’ve done nothing wrong, officer, or how about the video from a self proclaimed irreverent news organization from China that, via computer animation as if from an obsolete video game, replicated the trajectory from her house to the sensitive location as if it were a car chase, the abductors rushing to drag her father out of the car as if it were a drug bust, the video game representation of Ada recording her father’s capture with her phone from the backseat of the car, waterfalls of tears surging from her eyes, no not waterfalls, more like someone’s comical representation of lawn sprinklers superimposed on the eyes of the video game representation of me…

Apologies if I’ve let the run-on run on too long — but you’ll have wanted a taste of Cárdenas’s style, no? His sentences, unbroken and unrelenting, mimic the inexorability of history itself—cycles of erasure, resistance, recovery, and repetition. American Abductions is not just a novel about the present; it is a novel that recognizes the past has never ended. Its characters, trapped in linguistic torrents of grief and absurdity, seem painfully aware that history is repeating itself. And yet, as despairing as that recognition might be, American Abductions refuses to be silent. It makes its “statement of missingnessness” loud, insistent, impossible to ignore, resisting erasure, demanding we listen. Very highly recommended.

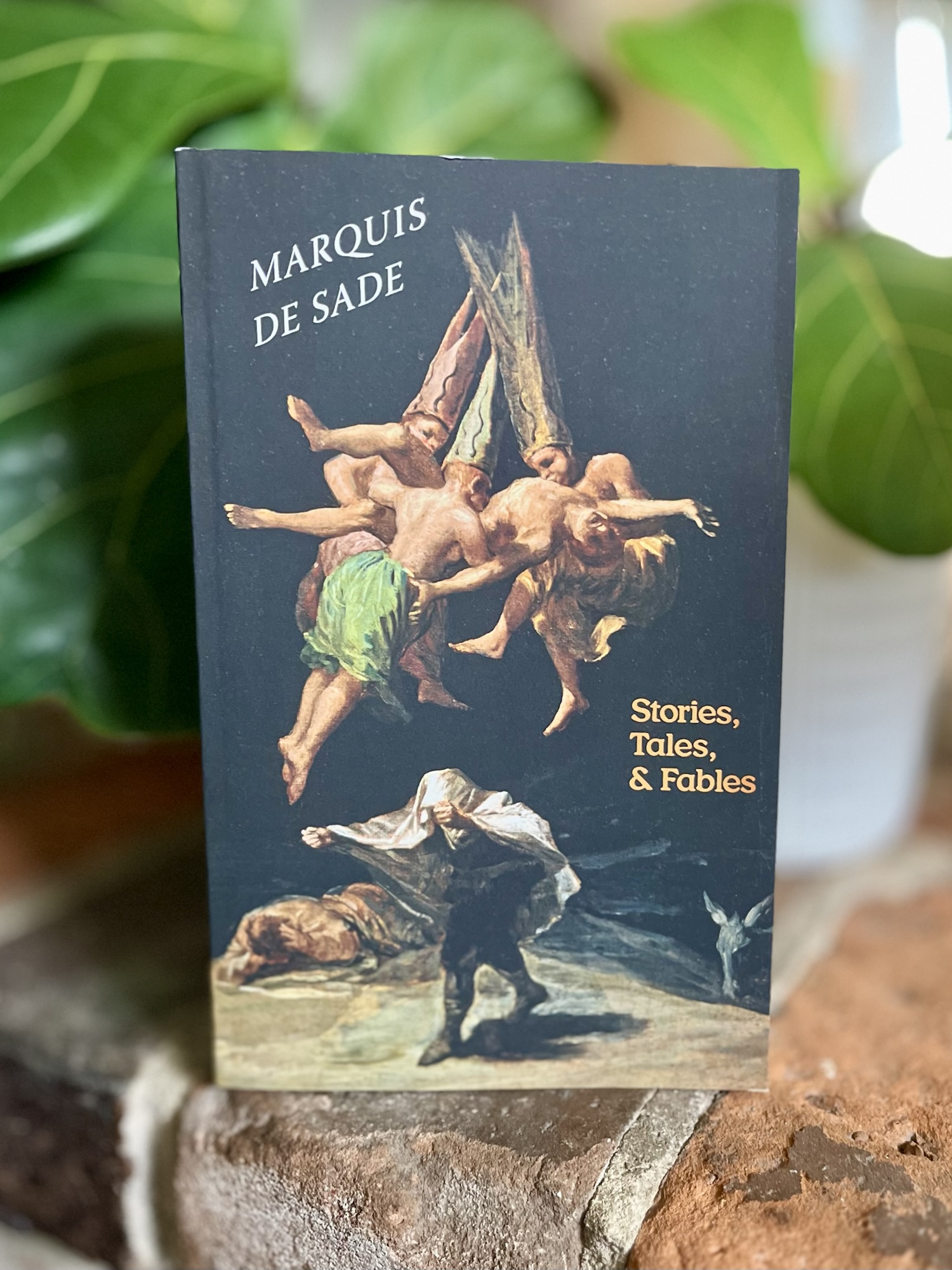

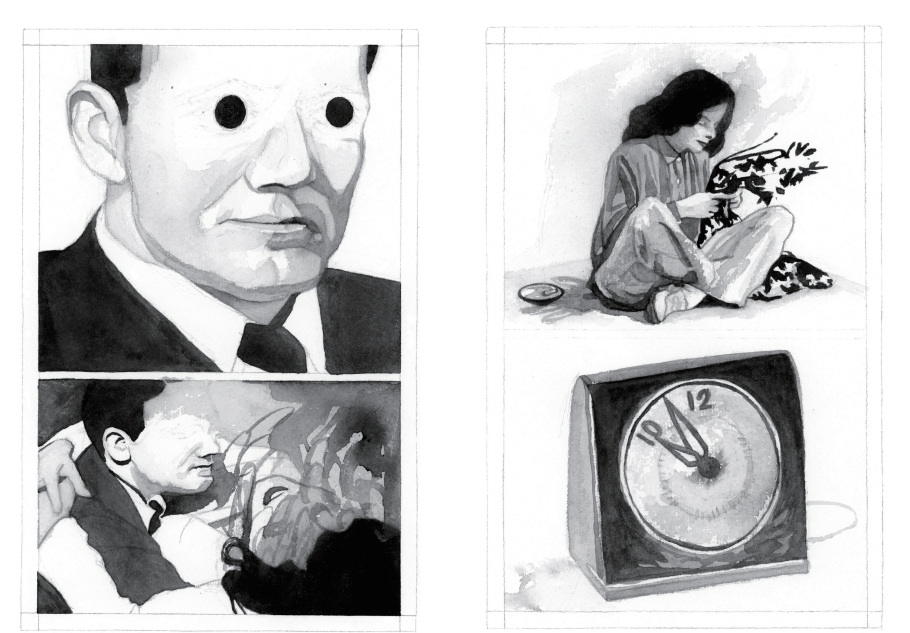

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of