Last year, Vulture put together a list of “100 Great Works of Dystopian Fiction,” and I wrote about it on my blog. The list was good fun, and there are a handful of novels on it I’m still keeping an eye out for (feel free to send me a copy of David Ohle’s Motorman, people).

Today, Vulture published another list of 100 books, this one ambitiously but cautiously titled, “A Premature Attempt at the 21st Century Canon.” The list begins with a nearly-900 word prefatory essay called “Why Now?” that isn’t bad but is perhaps unnecessary; the sentence, “We thought it might be fun to speculate (very prematurely) on what a canon of the 21st century might look like right now” is fine enough. I mean, look: List-making is fun. Putting together a syllabus or anthology or “canon” is fun. It generates conversation and maybe pisses folks off. And Vulture racked up a range of ringers to make their list—I have a lot of respect for many of the critics and writers who contributed here.

But ultimately, I think we all know that this canon is not a canon; it cannot be a canon because a canon evolves over time, and then evolves (or devolves or implodes or mutates or pick your verb) more. We don’t know what the most important books of the past eighteen years are yet, and most of us won’t be alive to know what they turn out to be. We would be better suited, really, to naming the canonical novels of 1900-1918 I suppose. But again, I think we all know that. Lists are fun. I take Vulture’s list to be a lovely set of reading recommendations from a set of smart folks.

I’ve already prefaced too much. I will go through the list, fairly quickly, in the order that Vulture prepared it, making comments or making none, occasionally recommending an alternative. I will write quickly without much reflection and I will undoubtedly forget a ton of books.

The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt (September 20, 2000)

For a few years now, almost every single reader whose taste I greatly admire has recommended DeWitt’s debut novel to me. I’ll admit that I didn’t care for her novel Lightning Rods at all, which seemed like the premise for a Ballard story stretched too thin over 200 or so pages. I am close to giving up on her short story collection Some Trick. I may be entirely misreading her. However, I admire the critic Christian Lorentzen, who helmed Vulture’s essay on The Last Samurai, and the fact that it came in number one on the list means that I’ll almost certainly give it a shot.

The Corrections, by Jonathan Franzen (September 1, 2001)

I recall chuckling at the part where the one son was drunk and doing some business with the lawn clippers. I suspect there’s some nostalgia at work with this one. Should I recommend a different book so early? Sure: Open City, by Teju Cole (February 8, 2011) is somehow absent.

Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro (March 3, 2005)

I can’t quibble. Reminds me that I want to read The Unconsoled

How Should a Person Be?, by Sheila Heti (September 25, 2010)

Autofiction! Maybe I should read it. In the meantime, may I recommend Writers, by Antoine Volodine (August 5th, 2016)?

The Neapolitan Novels, by Elena Ferrante (2011-2015)

Are these autofiction, too? I love these books. I would read a fifth one. And a sixth one. Etc.

The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson (May 5, 2015)

I downloaded the audiobook of this this summer but kept stalling, which is weird because it’s pretty short (Nelson reads it herself, too). Give it another shot.

2666, by Roberto Bolaño (November 11, 2008)

What can I say? There are seven review of 2666 posted on Biblioklept. I would’ve picked this as number one. Ten years after a hype cycle that could’ve withered a lesser book, 2666 seems as prescient as ever—not only in its content, but in its form—or really the welding of content and form, into one big dark dark big labyrinth-poem.

The Sellout, by Paul Beatty (March 3, 2015)

Another reminder that I don’t read enough contemporary fiction.

The Outline Trilogy (Outline, Transit, and Kudos), by Rachel Cusk (2014–2018)

Somehow Against the Day, by Thomas Pynchon (November 21, 2006) is not on this list, a fact that has nothing whatsoever to do with Cusk’s books, which I have not read.

Atonement, by Ian McEwan (September 2001)

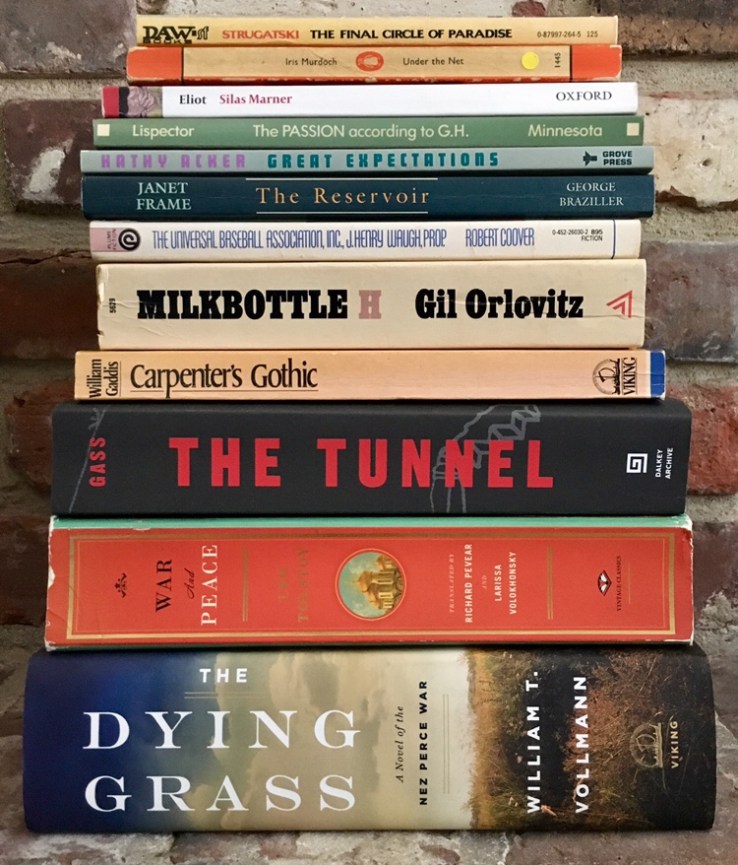

I found it a slog and an utter bore. Europe Central, by William T. Vollmann (2005) is somehow not on Vulture’s list.

The Year of Magical Thinking, by Joan Didion (September 1, 2005)

I remember reading it when it came out but I really don’t remember anything other than the premise. A Mercy, by Toni Morrison (November 11, 2008) is not on Vulture’s list

Leaving the Atocha Station, by Ben Lerner (August 23, 2011)

I hated 10:04 (Lerner’s follow up to Atocha Station) so much that I doubt I will ever read another book by the man. I loved loved loved Flee, by Evan Dara (2013) though.

The Flamethrowers, by Rachel Kushner (April 2, 2013)

Luc Sante is recommending The Flamethrowers, so maybe I should finally make time to read it.

Erasure, by Percival Everett (August 1, 2001)

Haven’t read any Everett; is this a good starting place?

Middlesex, by Jeffrey Eugenides(September 4, 2002)

A thoroughly passable entertainment that has no business on a list. Did you know that Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, by Chris Ware (2000) was published in the last 18 years also?

Platform, by Michel Houellebecq (September 5, 2002)

Houellebecq writes fascinating stuff, and his follow up The Possibility of an Island (2005) would fit in here too.

Do Everything in the Dark, by Gary Indiana (June 1, 2003)

Lorentzen’s write up of this one made me add it to a little note I keep on my iPhone of books to look out for.

The Known World, by Edward P. Jones (August 14, 2003)

Haven’t heard of it.

The Plot Against America, by Philip Roth (September 30, 2004)

I tried with Roth, I really did, and it just didn’t stick, none of it, just not for me. Point Omega, by Don DeLillo (February 2, 2010), is, in my estimation, one of the better novels of the post-9/11 zeitgeist (and really underrated as a DeLillo novel).

The Line of Beauty, by Alan Hollinghurst (October 1, 2004)

A really fantastic book that’s not on this list is Asterios Polyp, by David Mazzucchelli (July 7, 2009).

Veronica, by Mary Gaitskill (October 11, 2005)

I’ve enjoyed some of her short stories a lot.

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy (September 26, 2006)

It’s good. No Country for Old Men (2005) is probably better, but not as zeitgeisty.

Ooga-Booga, by Frederick Seidel (November 14, 2006)

Ooga-Booga is a fantastic name for a book.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz (September 6, 2007)

I recalled enjoying it fine, but it’s hardly canonical stuff, is it?

Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel (April 30, 2009)

I loved Bring Up the Bodies (May 8, 2012) very much too.

The Possessed, by Elif Batuman (February 16, 2010)

Always meant to read this and then never followed through.

The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, by Aimee Bender (June 1, 2010)

Mr. Fox, by Helen Oyeyemi (June 1, 2011)

Lives Other Than My Own, by Emmanuel Carrère (September 13, 2011)

Zone One, by Colson Whitehead (October 6, 2011)

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn (May 24, 2012)

NW, by Zadie Smith (August 27, 2012)

White Girls, by Hilton Als (January 1, 2013)

Mr. Fox looks good—but is it fantastic? I read Zone One but I guess it didn’t make a huge impression on me, because I don’t recall much besides the premise. White Teeth didn’t persuade me to read another of Smith’s books, but many smart people say they are good so.

My Struggle: A Man in Love, by Karl Ove Knausgaard (May 13, 2013)

Where are my Never Knuasgaards?

The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt (September 23, 2013)

Is this any good?

Dept. of Speculation, by Jenny Offill (January 28, 2014)

All My Puny Sorrows, by Miriam Toews (April 11, 2014)

Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine (October 7, 2014)

consent not to be a single being, by Fred Moten (2017–2018)

I’ve been copying and pasting the titles, authors, and dates from Vulture’s sites, and each time I have to remove their Amazon links.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, by Michael Chabon (September 19, 2000)

I will never understand the acclaim for this one. Never.

Also: Hey: If this Vulture list came out in, say, 2008, how many Jonathan Lethem books would be on it? How many Dave Eggers books?

The Amber Spyglass, by Philip Pullman(October 10, 2000)

Great stuff.

True History of the Kelly Gang, by Peter Carey (January 9, 2001)

I’m beginning to get tired of this post and I wished that I hadn’t started and I apologize to you, reader. Gerald Murnane seems like a writer to put on a list.

The Beauty of the Husband: A Fictional Essay in 29 Tangos, by Anne Carson (February 6, 2001)

I don’t know this one! Autobiography of Red came out in 1998 so it can’t go on the list, and thus proves lists are only foolish fun.

The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse, by Louise Erdrich (April 3, 2001)

This list is a huge reminder to me that I don’t read enough women. I try, but I think I don’t try hard enough.

Austerlitz, by W.G. Sebald (October 2, 2001)

A challenging book, and not the best starting place for Sebald, but also very rewarding. (Start with The Rings of Saturn (1995)).

Fingersmith, by Sarah Waters (February 4, 2002)

The Time of Our Singing, by Richard Powers (October 3, 2002)

The Book of Salt, by Monique Truong (April 7, 2003)

Mortals, by Norman Rush (May 27, 2003)

Home Land, by Sam Lipsyte (February 16, 2004)

I recall liking Home Land a lot, but canonical it ain’t. I tried with Richard Powers but it did not take.

Oblivion, by David Foster Wallace (June 8, 2004)

I’m tempted to write a whole mini-essay here in the middle of this damn thing about how Wallace’s literary stock seems to have fallen, at least to a broader audience, over the last few years. He seems like a target for handwringers to wring their hands over—and he (and, more importantly, his work) doesn’t even seem like the target—it’s his reputation and his fans that seem like the target. Anyway. I mean:

“Good Old Neon” is in Oblivion, and it belongs on the list.

Honored Guest, by Joy Williams (October 5, 2004)

Suite Française, by Irène Némirovsky (October 31, 2004)

The Sluts, by Dennis Cooper (January 13, 2005)

Voices From Chernobyl, by Svetlana Alexievich (June 28, 2005)

Magic for Beginners, by Kelly Link (July 1, 2005)

The Afterlife, by Donald Antrim (May 30, 2006)

Winter’s Bone, by Daniel Woodrell (August 7, 2006)

Wizard of the Crow, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (August 8, 2006)

American Genius, A Comedy, by Lynne Tillman (September 25, 2006)

Eat the Document, by Dana Spiotta (November 28, 2006)

Many casual readers may not know that Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851) was both a commercial and a critical flop—it essentially ended his writing career. The book found its audience among the modernist critics, writers, and readers of the 1920s though, and by the 1940s was generally esteemed as a canonical classic.

The Harry Potter novels, by J.K. Rowling (1997–2007)

Oh.

Sleeping It Off in Rapid City, by August Kleinzahler (April 1, 2008)

The White Tiger, by Aravind Adiga (April 22, 2008)

The Lazarus Project, by Aleksandar Hemon (May 1, 2008)

Home, by Marilynne Robinson (September 2, 2008)

Fine Just the Way It Is, by Annie Proulx (September 9, 2008)

Scenes From a Provincial Life: Boyhood, Youth, and Summertime, by J.M. Coetzee (1997–2009)

Notes From No Man’s Land, by Eula Biss (February 3, 2009)

Spreadeagle, by Kevin Killian (March 1, 2010)

There are 100 books on this list and somehow The Last Novel, by David Markson (2007) is not one of them.

Super Sad True Love Story, by Gary Shteyngart (July 27, 2010)

Seven Years, by Peter Stamm (March 22, 2011)

The Sense of an Ending, by Julian Barnes (August 4, 2011)

1Q84, by Haruki Murakami (October 25, 2011)

The Gentrification of the Mind, by Sarah Schulman (January 7, 2012)

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, by Ben Fountain (May 1, 2012)

Capital, by John Lanchester (June 11, 2012)

I’ve finally given in and admitted to myself that Haruki Murakami is Not For Me.

The MaddAddam Trilogy (Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood, and MaddAddam), by Margaret Atwood (2003-2013)

MaddAddam wasn’t especially good but Atwood’s first two are pretty good zeitgeisty affairs (and fun quick reads).

A Constellation of Vital Phenomena, by Anthony Marra (May 7, 2013)

Taipei, by Tao Lin (June 4, 2013)

Men We Reaped, by Jesmyn Ward (September 17, 2013)

Family Life, by Akhil Sharma (April 7, 2014)

How to Be Both, by Ali Smith (August 28, 2014)

A Brief History of Seven Killings, by Marlon James (October 2, 2014)

I’ll admit I’ve stopped reading even the blurbs at this point.

Preparation for the Next Life, by Atticus Lish (November 11, 2014)

A tremendous novel. The sort of thing that if you described the plot to me I’d, like, wave my hand as if to say, “Pass” — but, no, it’s so, so, so very good.

The Sympathizer, by Viet Thanh Nguyen (April 7, 2015)

The Light of the World, by Elizabeth Alexander (April 21, 2015)

The Broken Earth trilogy, by N.K. Jemisin (2015-2017)

What Belongs to You, by Garth Greenwell (January 19, 2016)

Collected Essays & Memoirs (Library of America edition), by Albert Murray (October 18, 2016)

The Needle’s Eye, by Fanny Howe (November 1, 2016)

Ghachar Ghochar, by Vivek Shanbhag (February 7, 2017)

The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas (February 28, 2017)

All Grown Up, by Jami Attenberg (March 7, 2017)

The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir, by Thi Bui (March 7, 2017)

Tell Me How it Ends, by Valeria Luiselli (March 13, 2017)

Priestdaddy, by Patricia Lockwood (May 2, 2017)

Red Clocks, by Leni Zumas (January 16, 2018)

Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday (February 6, 2018)

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, by Denis Johnson (January 16, 2018)

Johnson’s novel isn’t last on the list—Halliday’s is—(and I don’t think “last” is anything but chronology for the authors near the end of the list)—but I’ve read it and I love it (and it’s another write up from Lorentzen)—but it’s not a canonical work. It’s great, and it somehow manages to match Johnson’s best early stuff, but again—not canonical. Although of course I could be wrong.

What I think is this:

For a while, we’ll see the canon, or The Canon if you prefer—and just as significantly, the idea of a literary canon–increasingly atomized, interrogated, personalized, and deconstructed (and perhaps neglected, at least from an academic standpoint). It doesn’t matter. The work of today’s literary darlings may be the foamy flotsam and jetsam of tomorrow. But of course you’ll be dead—I mean I’ll be dead—what I’m saying is we’ll be dead, so it doesn’t matter. We could pretend to be, like, Stewards of the Canon or something—hope for a cultural continuity (or discontinuity) that preserves (or disrupts) Certain Literary Values (Ours!)—or maybe just accept that reading is a bit of pleasure, a bit of fun, and that we antecede those who will decide, a hundred years from now, what the 21st-century canon really is.