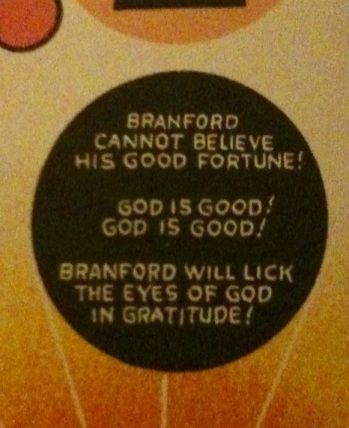

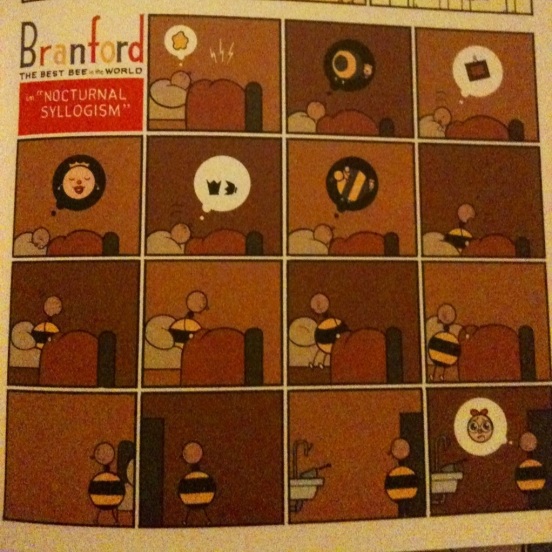

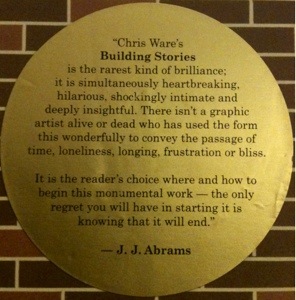

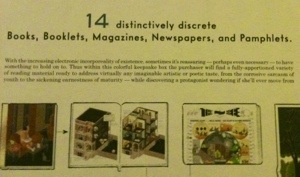

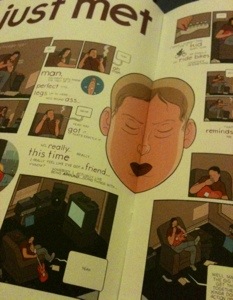

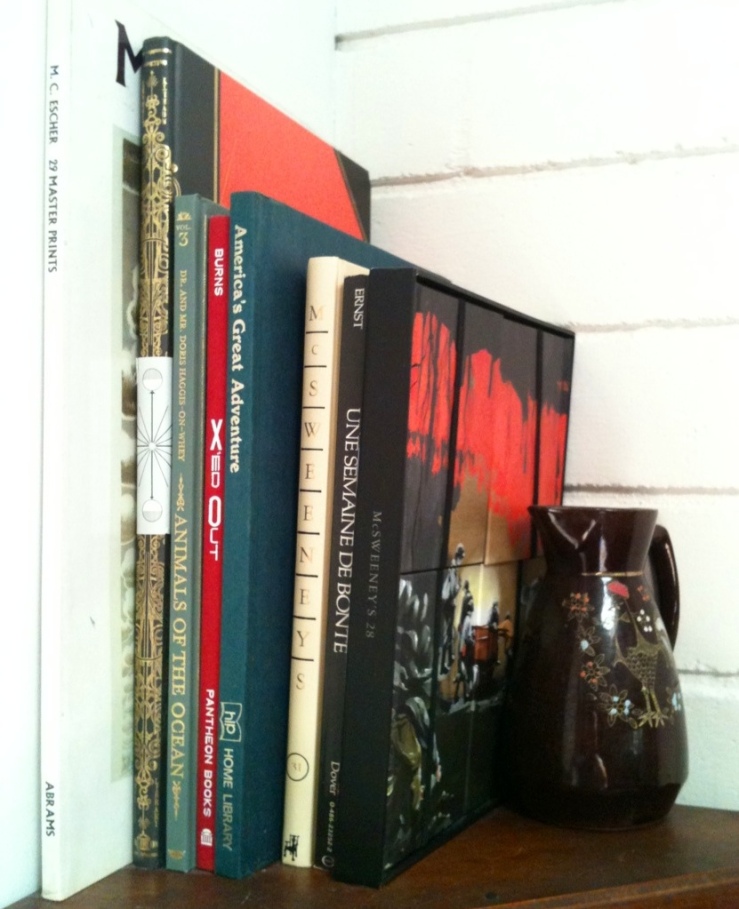

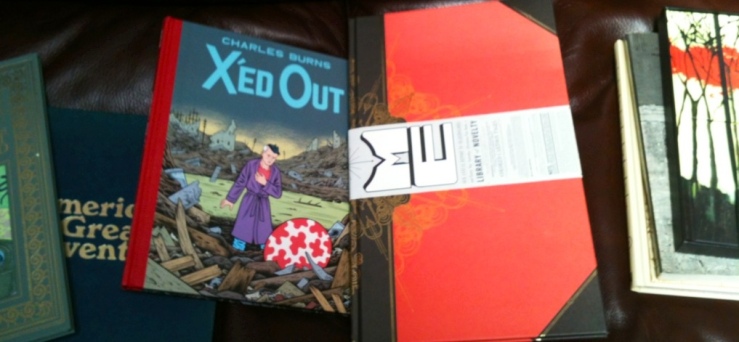

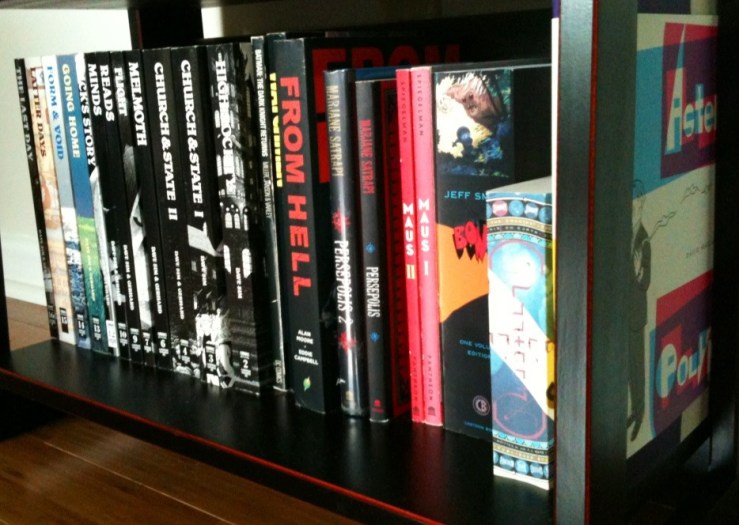

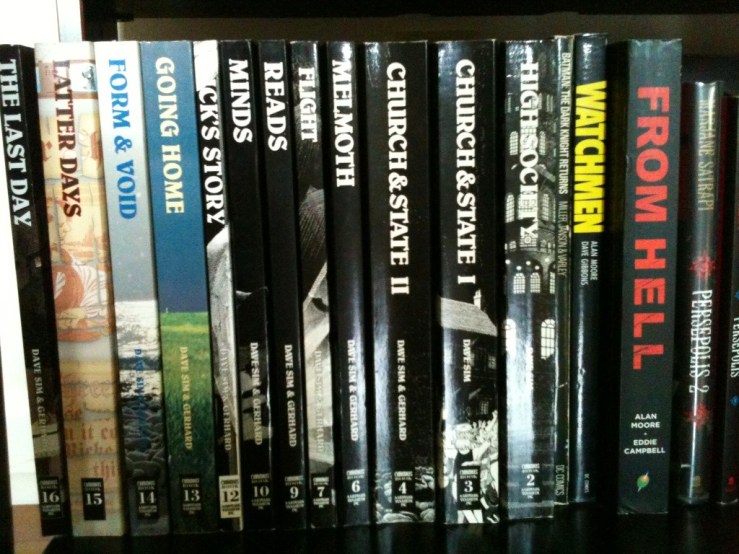

September 23rd, 2000 is one of the longer pieces in Chris Ware’s box set, Building Stories. Part of the joy and frustration of Building Stories is its free form—the possibility of reading one piece before another, of getting one tale or perspective before another. I started with Branford, which seems in retrospective a fairly neutral opening—it introduces many of the themes that develop in Building Stories but none of the major characters. I then read I just met, which introduces a couple suffering a sour relationship.

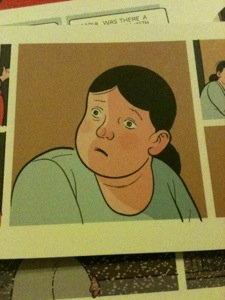

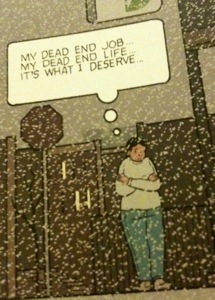

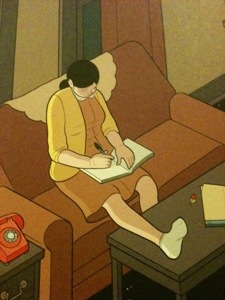

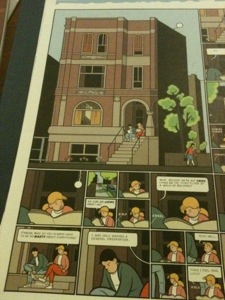

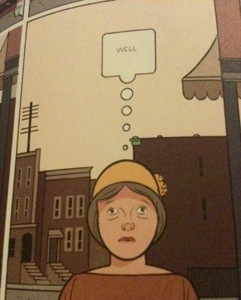

September introduces (to me, anyway), two major “new” (again, “new” to me; these characters appear central in other books and pamphlets of the collection and obliquely in others): The “lonely girl,” a would-be artist sporting a prosthetic leg, and the “old lady,” landlord of the building. Most of September takes the form of lonely girl’s diary entries.

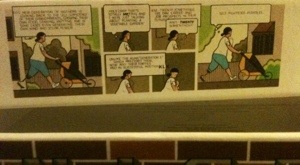

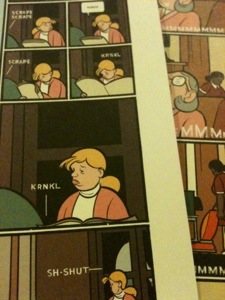

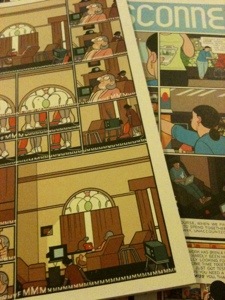

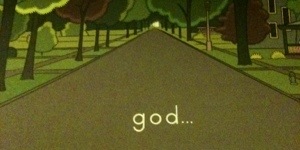

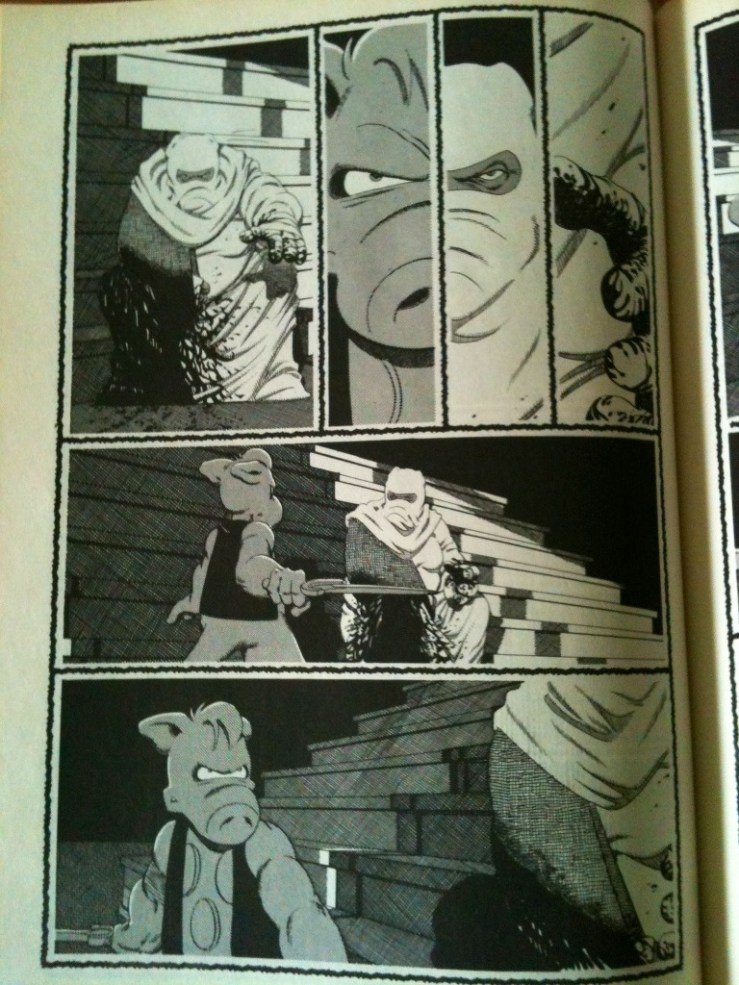

I noted two characters (again, new to me), but the building itself also gets a voice and prominent role in September; its thoughts and memories frame the narrative:

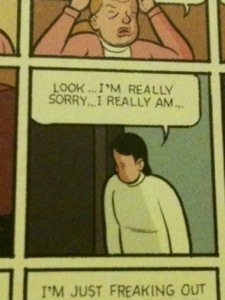

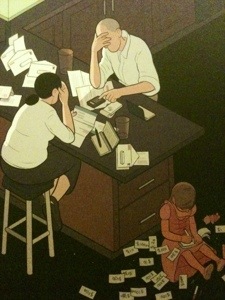

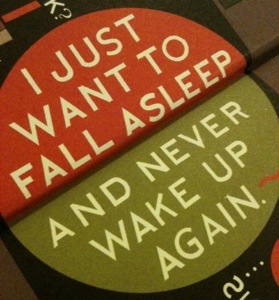

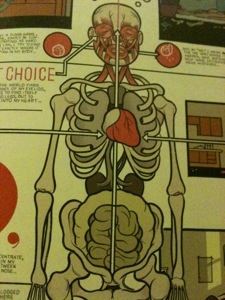

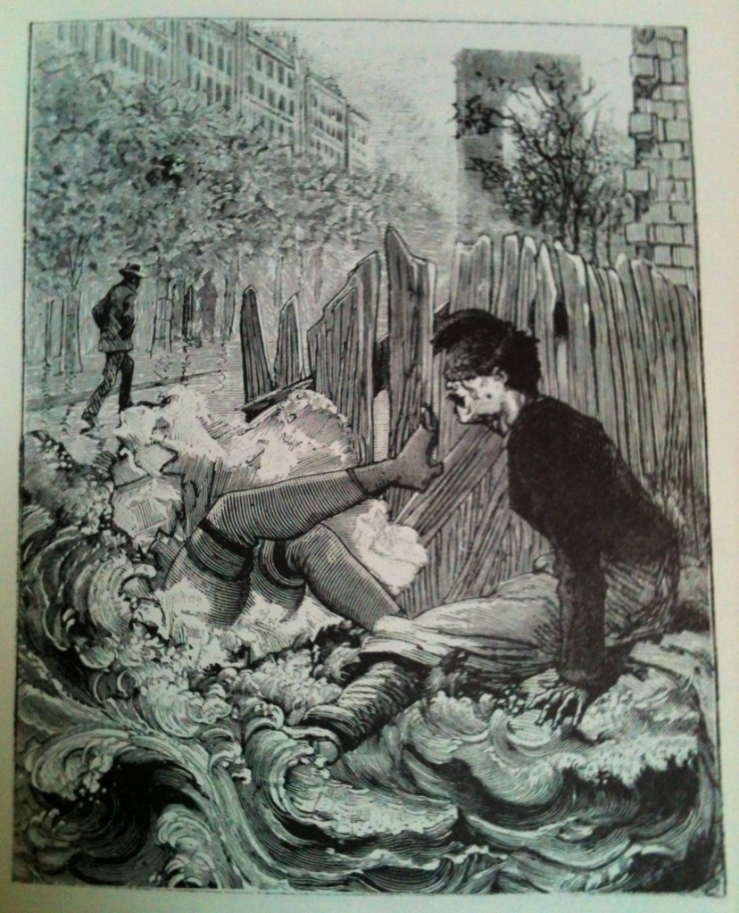

September frames the repetitions, the loops, the patterns that undoubtedly will resurface throughout Building Stories. We get access to the characters dreams, which seem to overlap and echo each other—and then repeat in real life, albeit in other forms. The landlady, recalling her youth, seems to echo the loneliness and despair of the lonely girl, as well as the pain of the woman in the sour relationship. We see that the building has in fact been a kind of prison for her, preventing her from forming real relationships:

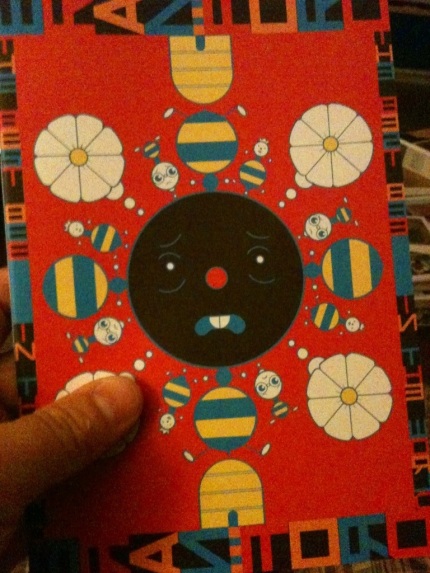

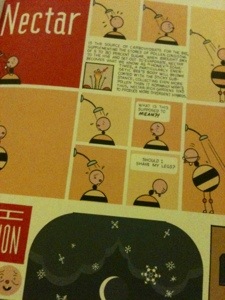

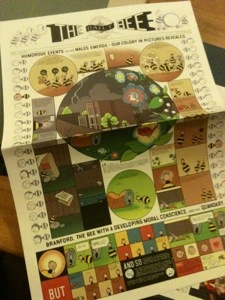

Other echoes are more subtle—a close up of a bee, for instance, either foreshadows or calls back to (or both, of course) Branford, the Best Bee in the World.

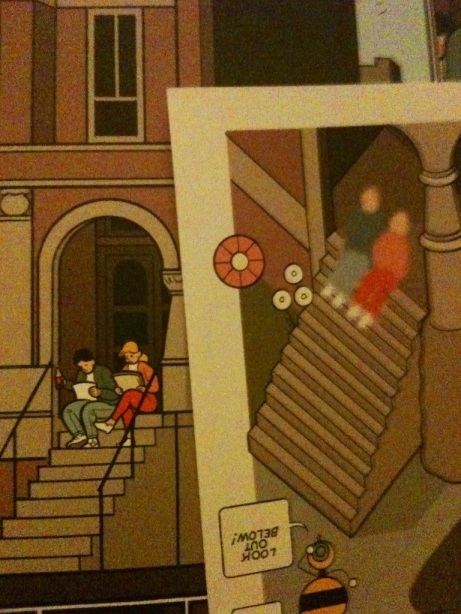

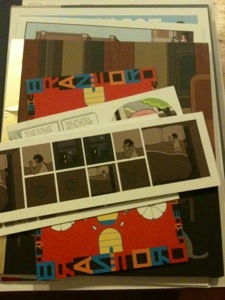

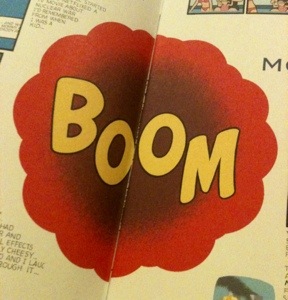

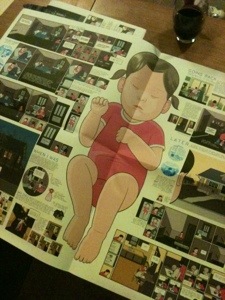

We can see the Branford episode again, here in the tiny detail of a soda can, a major setting for that episode. I was more fascinated by the newspaper though, particularly the colorful squares of a comics section, a reference Ware’s medium and perhaps a visual suggestion of Building Stories itself. The detail is tiny, but meaningful:

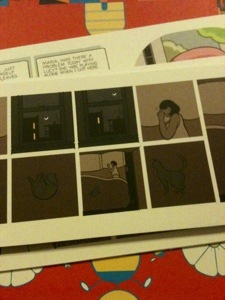

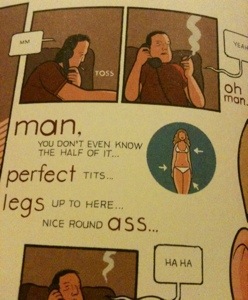

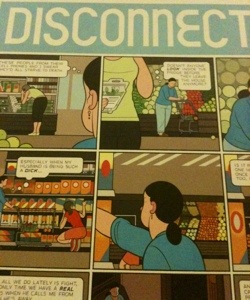

In a later part of September, we see a direct reference to the end of I just met:

I imagine that there were other references, call backs, and echoes in September that I won’t get until later.

The story—well, it’s beautiful, a perfect short story, self-contained but thematically resonant with the larger project. The ending is so damn sweet and perfect that it brought a little tear to my eye. And yet: Was that the ending? Of course not. The sense of rhetorical resolution—that is to say the so-called happy ending—will almost surely be punctured, deflated, or otherwise complicated by one of the next texts I read. More to come.