PREVIOUSLY:

PREVIOUSLY:

Introductions + stories 1956-1959

IN THIS RIFF:

Stories published in 1960:

“The Sound-Sweep”

“Zone of Terror”

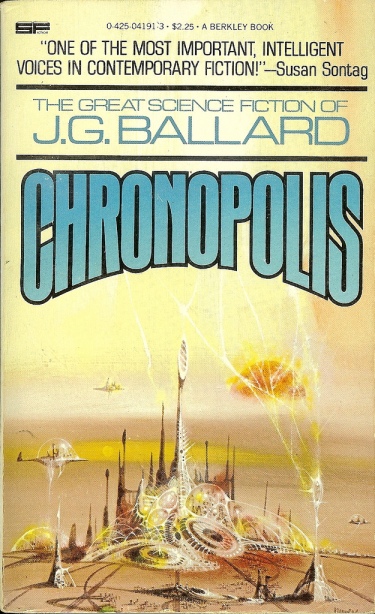

“Chronopolis”

“The Voices of Time”

“The Last World of Mr. Goddard”

1. “The Sound-Sweep” (1960)

Ballard’s strong suit isn’t characterization. In his later writing, he transcends this apparent weakness, employing a style and rhetoric that dispenses with—or nakedly accepts, in some cases—the flatness of his characters. Ballard works in types: the scientist, the madman, the artist, the detective, the ingenue, the explorer, the has-been. Most of his characters are driven by very basic desires—curiosity, madness, revenge. There’s a thin line though between archetypal placeholders and hackneyed stereotypes, and Ballard occasionally stumbles over it in some of these early stories. “The Sound-Sweep” is one such story, plodding along over too many pages, asking its readers to care about characters that lack emotional or psychological depth. And while I don’t think we read Ballard for emotional depth, necessarily, we do read Ballard’s best work because it plumbs the contours of human psychology colliding into nascent technological changes that affect the most basic human senses.

As its title suggests, “The Sound-Sweep” is another early Ballard tale that takes on the sense of sound. The short version: This is a story about noise pollution, and also about how we might sacrifice an artistic way of listening in favor of apparent convenience. As is often the case in these early stories, Ballard constructs the tale to explore the fallout of one particular idea. In this case, that’s “ultrasonic music”:

Ultrasonic music, employing a vastly greater range of octaves, chords and chromatic scales than are audible by the human ear, provided a direct neural link between the sound stream and the auditory lobes, generating an apparently sourceless sensation of harmony, rhythm, cadence and melody uncontaminated by the noise and vibration of audible music. The re–scoring of the classical repertoire allowed the ultrasonic audience the best of both worlds. The majestic rhythms of Beethoven, the popular melodies of Tchaikovsky, the complex fugal elaborations of Bach, the abstract images of Schoenberg – all these were raised in frequency above the threshold of conscious audibility. Not only did they become inaudible, but the original works were re–scored for the much wider range of the ultrasonic orchestra, became richer in texture, more profound in theme, more sensitive, tender or lyrical as the ultrasonic arranger chose.

To tease out this idea, Ballard employs a washed-up opera singer, Madame Giaconda (a heavy base of Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond with a heavy dash of Miss Havisham and cocaine), and Mangon, a mute orphan, the titular sound-sweep (should I wax on the Blakean undertones here? No? Okay).

“The Sound-Sweep” plods along over far too many pages, even divvying up the plot into chapters, asking us to care about the relationship between Giaconda and Mangon. The story would probably have made an excellent episode of The Twilight Zone, where performers might give life to some of the flat dialogue here and the constraints of television might compress the plot. The most interesting thing about “The Sound-Sweep”: The tale in some ways anticipates the mp3 and the ways in which music will be consumed:

But the final triumph of ultrasonic music had come with a second development – the short–playing record, spinning at 900 r.p.m., which condensed the 45 minutes of a Beethoven symphony to 20 seconds of playing time, the three hours of a Wagner opera to little more than two minutes. Compact and cheap, SP records sacrificed nothing to brevity. One 30–second SP record delivered as much neurophonic pleasure as a natural length recording, but with deeper penetration, greater total impact.

2. “Zone of Terror” (1960)

Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” is a much better doppelganger story. “Zone of Terror” reads like a very rough sketch for some of the stuff Ballard will do in his 1962 novel The Drowned World. (Both “Chronopolis” and “The Voices of Time” also clearly anticipate The Drowned World, each with much stronger results).

3. “Chronopolis” (1960)

“Chronopolis” offers an interesting central shtick: Clocks and other means of measuring and standardizing time have been banned. But this isn’t what makes the story stick. No, Ballard apparently tips his hand early, revealing why measuring time has been banned—it allows management to control labor:

‘Isn’t it obvious? You can time him, know exactly how long it takes him to do something.’ ‘Well?’ ‘Then you can make him do it faster.’

But our intrepid young protagonist (Conrad, his loaded name is), hardly satisfied with this answer, sneaks off to the city of the past, the titular chronopolis, where he works to restore the timepieces of the past. “Chronopolis” depicts a technologically-regressive world that Ballard will explore in greater depth with his novel The Drowned World, but the details here are precise and fascinating (if perhaps ultimately unconvincing if we try to apply them as any kind of diagnosis for our own metered age). Ending on a perfect paranoid note, Ballard borrows just a dab of Poe here, synthesizing his influence into something far more original, far more Ballardian. Let’s include it in something I’m calling The Essential Short Stories of J.G. Ballard.

4. “The Voices of Time” (1960)

“The Voices of Time” is easily the best of the early stories in the collection. Ballard allows himself to dispense almost entirely with plot, or at least the kind of plot he’s been thus-far constrained by. Instead of the neat concision of his nineteenth century forebears (Chekhov and Poe), Ballard moves to something far more Ballardian (excuse the repetition), opening his text to a range of images and phrases that will repeat throughout his career—the word terminal, drained vessels, cryptic designs and sequences, a kind of psychic detritus the reader is left to account for and monitor. The loose threads in “The Voices of Time” are too many to enumerate. There’s a mutant armadillo and a girl named Coma. Mass narcolepsy and cacti that absorb gold from the earth as a shield against radiation. And sleep. And de-evolution:

…thirty years ago people did indeed sleep eight hours, and a century before that they slept six or seven. In Vasari’s Lives one reads of Michelangelo sleeping for only four or five hours, painting all day at the age of eighty and then working through the night over his anatomy table with a candle strapped to his forehead. Now he’s regarded as a prodigy, but it was unremarkable then. How do you think the ancients, from Plato to Shakespeare, Aristotle to Aquinas, were able to cram so much work into their lives? Simply because they had an extra six or seven hours every day. Of course, a second disadvantage under which we labour is a lowered basal metabolic rate – another factor no one will explain. …

… It’s time to re–tool. Just as an individual organism’s life span is finite, or the life of a yeast colony or a given species, so the life of an entire biological kingdom is of fixed duration. It’s always been assumed that the evolutionary slope reaches forever upwards, but in fact the peak has already been reached, and the pathway now leads downward to the common biological grave. It’s a despairing and at present unacceptable vision of the future, but it’s the only one. Five thousand centuries from now our descendants, instead of being multi–brained star–men, will probably be naked prognathous idiots with hair on their foreheads, grunting their way through the remains of this Clinic like Neolithic men caught in a macabre inversion of time. Believe me, I pity them, as I pity myself. My total failure, my absolute lack of any moral or biological right to existence, is implicit in every cell of my body…

I harped on Ballard’s lack of characterization earlier, and “The Voices of Time” makes no strong case for its author’s ability to create deep, full characters. What Ballard does very very well though is harness, express, and communicate the intellect of his smart, smart characters—something many if not most other writers (contemporary or otherwise) can’t do, despite any technical prowess they may possess. “The Voices of Time” doesn’t just tell you that its heroes and antiheroes are brilliant (and/or mad)—it shows you.

Marvelous stuff. Include it in The Essential Short Stories of J.G. Ballard

5. “The Last World of Mr. Goddard” (1960)

More Twilight Zone stuff. God-dard. Lilliput, sort of. Doll’s house. Etc. A one-note exercise that I doubt is worth your time. Skip it.

6. On the horizon:

Ballard anticipates how hollow and stale contemporary writing will become in “Studio Five, The Stars.”

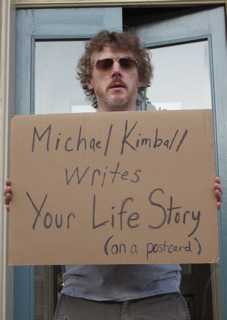

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…