The loose, brief breeziness of Barry Hannah’s 1987 novella Hey Jack! belies the terror and rage at the heart of this hilarious tragedy. It’s a slim volume—133 pages in my hardback copy—with the same rambling flightiness that characterizes Hannah’s better known 1980 novel-in-vignettes, Ray.

Hey Jack! bears many comparisons with Ray: Like Ray, this novel is told from the perspective of a war vet (Korea this time, not ‘Nam); like the eponymous speaker of Ray, the narrator of Hey Jack!, Homer, finds himself frequently besotted, binged out, or horny; like Ray, Homer tries to make a marriage work; like Ray, Homer comes into conflict with a poor white trash family.

And like Ray, Hey Jack! tests the boundaries of what is and is not a “novel.” Hey Jack! is discontinuous and meandering; there’s a plot, sure, but Hannah’s apt to jump over place and time freely, tripping over months at a time, sparing not even a sentence to cue his readers in the right direction. No exposition here, folks. I suppose I should summarize the plot though: Homer, passing middle age, takes up a friendship with Jack, an older man, a former sheriff and fellow Korean War vet who runs a coffee shop popular with the college kids. Together, the pair (sort of) face off against Ronnie Foot, a local boy turned rock star who has the gall to begin an affair with Jack’s forty-year old daughter:

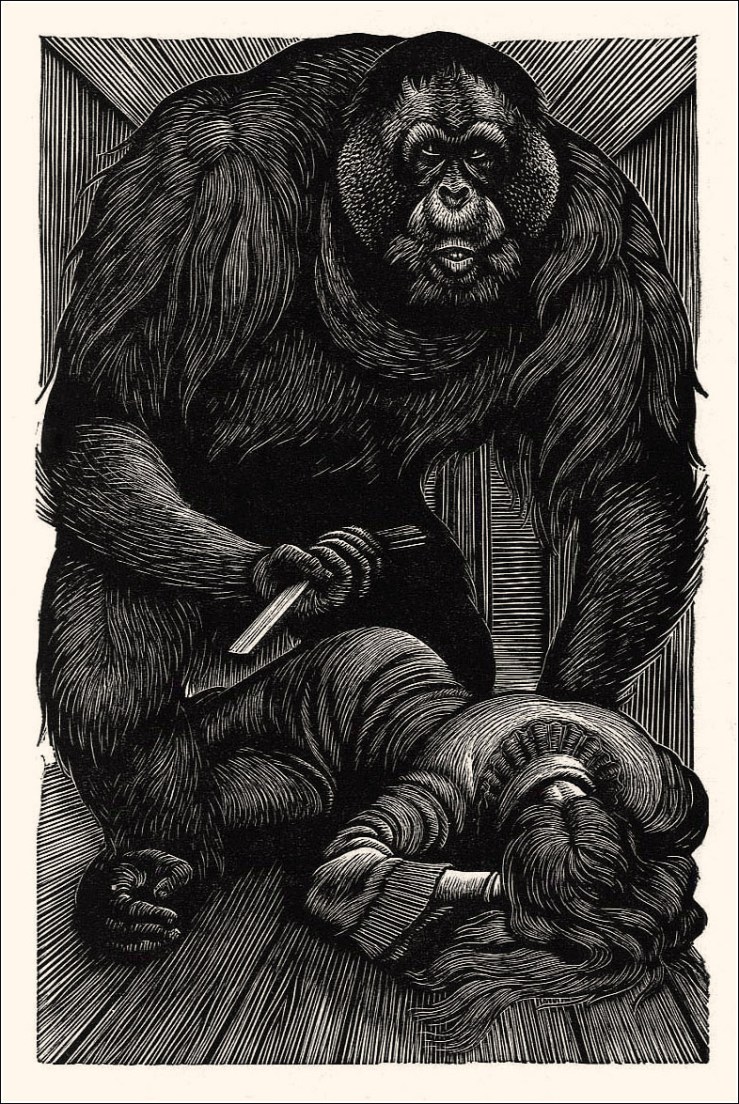

Ronnie Foot, the rock star had her. Or Jack thought he had her, he was sure he had her. Jack was mumbling. Jack was talking about ingratitude and pride and scum hanging on meat, things of that nature. It was astonishing to see him creep and rise suddenly, like a crazy old man. . . . “Nobody ever had a daughter like me. You want me to just her go, like a fart?” He was fingering the gun again.

Jack, once the lone bastion of sanity and order in Homer’s small, chaotic Mississippi town, begins to slide into the insanity and violence that marks the rest of the populace. Jack’s stability is the closest thing Hey Jack! offers as a slice of normalcy (to be clear though, Hannah’s characters skew grotesque, not quirky).

What unites the volume isn’t Jack’s slow slide to the dark side, but rather the narrative’s distinctive, ornery voice. It’s worth quoting Homer at length; here he condenses several of the novel’s themes in the sort of crazy-or-wise? rant indicative of the novella’s tone and rhythm:

In love, in love, in love. A mule can climb a tree if it’s in love. A man like me can look himself in the mirror and say, I’m all right, everything is beloved, I’m no stranger to anywhere any more. I’m a man full of life and a lot of time to kill, shoot every minute down with a straight blast of his eye across the bountiful landscape, from the minnow to the Alps. Something looks back at you with an eye of insane approval. Something looks back at you; out of belligerent ignorance of you it has come to a delighted focus on you and your love, together, sending up gasses of collision that make a rainbow over the poor masses who are changing a tire on the side of the road on a hot Saturday afternoon, felling like niggers. There is a law that every nigger spends a quarter of every weekend changing tires, my friend George, the biochemist, says. What do we know? What do we mere earthlings, unpublished and heaving out farts like puzzled sighs, know, but what is in our blood? I had broken up once with a woman who was in Europe, and coming out of the mall movie (I don’t even remember the movie) I gave out this private marvelous fart that was equal to a paragraph of Henry James, so churned were my guts and so lingering. And I was free. Free to discuss it. Delighted in the boundless ignorance and destruction that lay out there under the dumb lit cold moon. Enough about me and my poetry.

There’s so many shifts here. Hannah’s Homer comes off like a besotted barstool philosopher, gazing at his navel through an empty tumbler and finding both gut and abyss. We see the casual racism that so many of Hannah’s characters dip into; we see the conflation of art, spirit, and expulsion. Need I comment on the fart joke? It’s worth just repeating: “I gave out this private marvelous fart that was equal to a paragraph of Henry James” — if you don’t like that you’re not going to like Hey Jack!

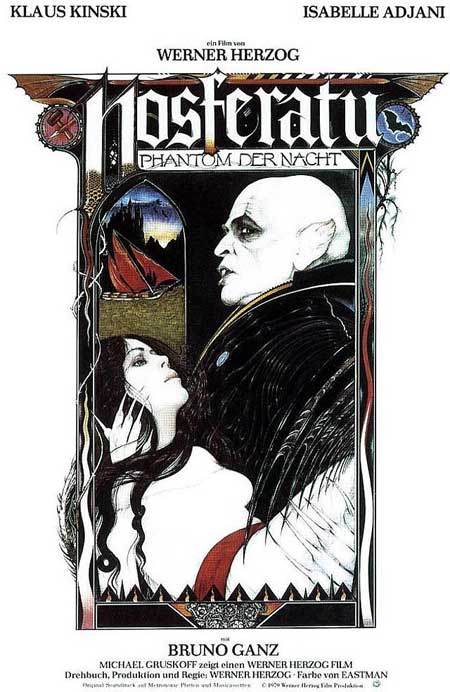

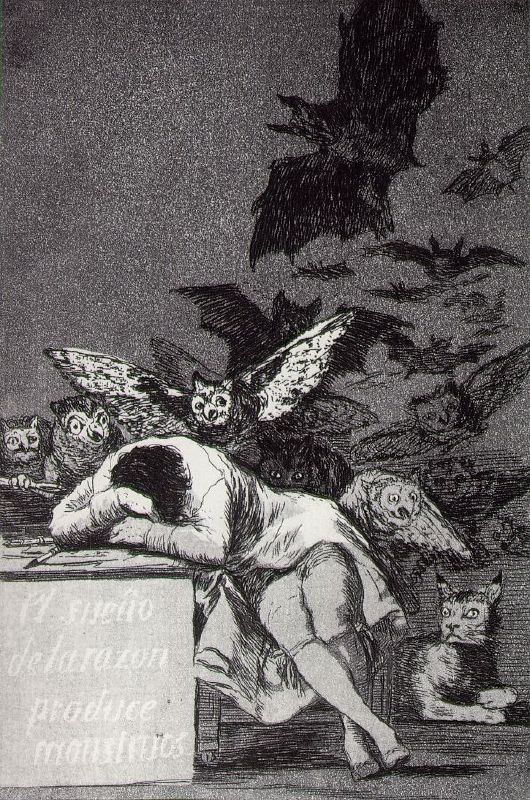

Beyond that voice, there’s little to organize Hey Jack!—it’s a riff, sometimes a howl, often a jape, a joke, sometimes a verbal slap. This isn’t to say there isn’t a trajectory to the novella or a payoff at the end. Hannah seems unable to resist a tragic arc, the same one he pulls through the whiskey haze of Ray. Perhaps he takes his cues from Edgar Allan Poe’s essay “The Philosophy of Composition“: ” . . . the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” (To be fair Poe is hardly the first fella to find a dead beauty such a worthy topic; also, I’ve never really been sure how to measure the tone of his essay—I can’t help but think he’s being somehow simultaneously tongue-in-cheek and deadly earnest. But enough about Poe).

But arcs be damned. The best bits of Hey Jack! are the stray little paragraphs that erupt from nowhere either to fizzle out or burn up in a bang. At its best, the novella offers bizarre little stories piecemeal that read equally absurd and true. To wit:

I began hollering at my wife for her shortcomings. She left the house, 11 P.M. I’d quit drinking and smoking. She brought me back a bottle of rye and a pack of Luckies, too. I hadn’t smoked for two weeks. I must have been a horrible nuisance.

I took a drink and a smoke.

Then I was normal. My lungs and my liver cried out: At last, again! The old abuse! I am a confessed major organ beater. I should turn myself in on the hotline to normalcy.

I hope by now that you have a sense of whether or not Hey Jack! is for you. It’s probably not going to gel with most readers: Too ugly, too loose, too nihilistic, perhaps; at heart a sloppy affair . . . but I loved it—it was the perfect book to riffle through over a few Saturday or Sunday afternoons on my back porch, its pages blotting up the condensation from a glass of sangria or can of beer, Homer’s consciousness as loose and discontinuous as my own. Not the best starting place for those interested in Hannah—that might be Airships—but great stuff.

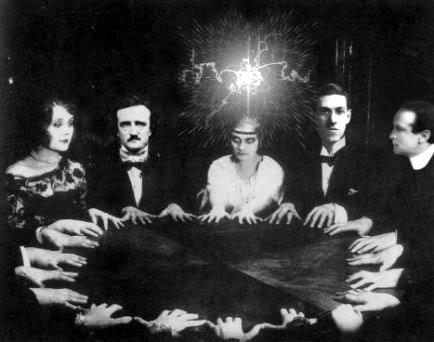

In the past few years we’ve seen a spate of books where public domain characters and historical figures feature in supernatural tales, usually written in an ironic, or at least parodic mode. It seems like a heavy percentage of these books are mixed up somehow with Jane Austen, whose legacy has become grist for a literary cottage industry, with a new “re-imagining” of Pride and Prejudice or Sense and Sensibility coming out every season. Last year, Michael Thomas Ford offered the public the mix of Jane Austen and vampires we had been so desperately clamoring for, Jane Bites Back. By way of a little more context (and pure laziness), I’ll quote

In the past few years we’ve seen a spate of books where public domain characters and historical figures feature in supernatural tales, usually written in an ironic, or at least parodic mode. It seems like a heavy percentage of these books are mixed up somehow with Jane Austen, whose legacy has become grist for a literary cottage industry, with a new “re-imagining” of Pride and Prejudice or Sense and Sensibility coming out every season. Last year, Michael Thomas Ford offered the public the mix of Jane Austen and vampires we had been so desperately clamoring for, Jane Bites Back. By way of a little more context (and pure laziness), I’ll quote  Jane’s editor decides to become an agent and leaves her with Jessica Abernathy (evil nemesis in Batty); Jane has to run constant interference on her wacky/charming friend Lord Byron (also a vampire, of course); etc., etc., etc. The most ridiculous/campiest plot device of all though is that Jane is converting to Judaism to please her boyfriend Walter’s judgmental mom. Yes. That’s right. We also learn that Jane played Magenta in a traveling production of The Rocky Horror Picture Show in the seventies, a minor detail to be sure, but one that seems to reinforce Ford’s whimsical kitsch. Batty aims for a kind of sassy brevity in its scene constructions, and while its certainly not a book for me, I think that those who want to see Jane Austen as a 21st century vampire will probably enjoy it quite a bit. Jane Goes Batty is new in trade paperback from

Jane’s editor decides to become an agent and leaves her with Jessica Abernathy (evil nemesis in Batty); Jane has to run constant interference on her wacky/charming friend Lord Byron (also a vampire, of course); etc., etc., etc. The most ridiculous/campiest plot device of all though is that Jane is converting to Judaism to please her boyfriend Walter’s judgmental mom. Yes. That’s right. We also learn that Jane played Magenta in a traveling production of The Rocky Horror Picture Show in the seventies, a minor detail to be sure, but one that seems to reinforce Ford’s whimsical kitsch. Batty aims for a kind of sassy brevity in its scene constructions, and while its certainly not a book for me, I think that those who want to see Jane Austen as a 21st century vampire will probably enjoy it quite a bit. Jane Goes Batty is new in trade paperback from